Casey Dreier • Dec 10, 2013

Top NASA Scientists Grapple with Budget Cuts

Top NASA scientists tried to focus on the bright side Monday, highlighting the unprecedented productivity of current space science missions, despite a continued future of diminishing budgets.

Dr. Ellen Stofan, NASA's Chief Scientist, and Dr. John Grunsfeld, the head of NASA's Science Mission Directorate and Hubble-repair astronaut, both emphasized the breadth of science returns at the 2013 American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

"The positive thing about meetings like this is that you see our results getting an enormous amount of press and an enormous amount of support and interest from the American people," said Dr. Stofan. "And the more we have that, the more we’re doing our job.”

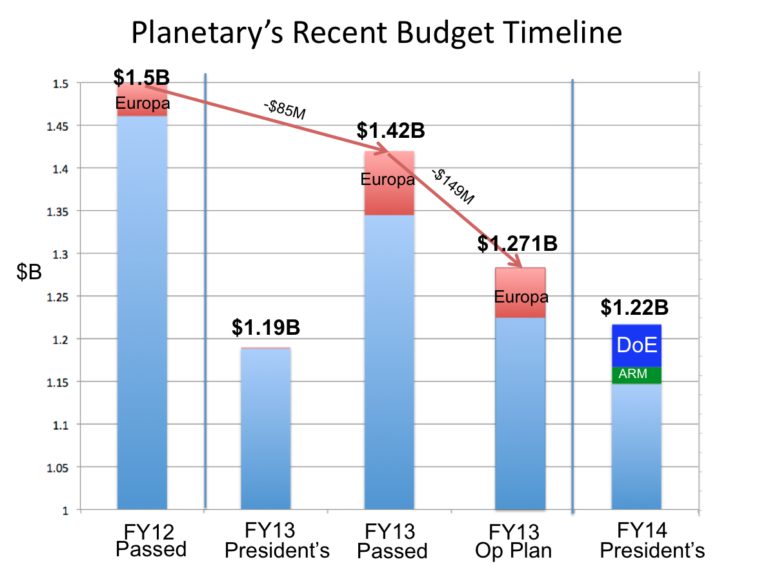

The first few questions from the press were about the unusually harsh cuts to NASA's Planetary Science Division in recent years, including more than $200 million in cuts proposed in 2014. In response, Grunsfeld listed a number of missions currently operating in space, keeping the focus off the upcoming mission gap in the second half of this decade. He also highlighted the two planetary missions currently in development.

“We have plans to go visit [the asteroid] Bennu with OSIRIS-REx to bring back a pretty substantial sample. We are back involved with ExoMars 2016 and 2018. We have InSight, a geophysical monitoring station on Mars, and an AO for 2020 Mars on the street,” Grunsfeld said.

OSIRIS-REx is a medium-class planetary mission that is scheduled to launch in 2016. InSight, a small Discovery-class mission, is also slated for 2016. NASA is contributing a non-scientific communications package to the European Trace-Gas Orbiter in 2016 and the Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer (MOMA) instrument on the ExoMars lander in 2018.

“Given the tough fiscal climate, I actually feel very proud of how we’ve been able to try and address almost all of the high-priority items in the Decadal Surveys," Grunsfeld said. "The one we have the most problem with is the cadence of missions. We are constrained in missions.”

Mission cadence refers to how often NASA can fly a new spacecraft. Keeping a regular cadence is crucial for a healthy scientific community and a reliable industrial base for engineering design and construction.

The National Research Council's Decadal Survey, which is the official consensus of the scientific community, recommends flying small missions (Discovery-class) every two years, medium missions (New Frontiers-class), every five years, and a flagship once every decade.

When asked about the next opportunities for scientists to propose small- and medium-class missions, Jim Green, the Director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division said that NASA is planning to release a draft Discovery mission announcement in 2014. Preparing a draft now, he said, will allow NASA to react quickly if Congress adds more money to the Planetary Science Division before the year ends.

Green said that the next New Frontiers-class mission will be selected after the peak funding requirements for OSIRIS-REx are met, which is likely to be after 2015.

These releases are just the "Announcements of Opportunity," which begin a multi-year process of mission selection. Given that no selection will be made before 2016 or 2017, it’s likely that the soonest a new mission would be ready to fly would be 2021 or 2022. The Clipper Europa mission concept, currently estimated at $2.1 billion, remains off the table.

But NASA is trying to find creative ways to work within their constraints. Said Grunsfeld: "I’ve challenged [our program managers] to look at other options: what about Discovery and a half? Or New Frontiers and half? Not a flagship, but something that would allow us to do one of these challenging missions. The spirit is: let’s use technology and use some of our capabilities to see if we can do 70% of the science objectives of, say, a Europa mission, at half the cost. That might be worth the trade.”

“If budgets were increasing, we could do more,” he said.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth