Bruce Betts • Oct 08, 2013

Our Improved Optical Search for ET

The Planetary Society Optical SETI (OSETI) Telescope was successfully upgraded and fully tested, and is now fully operational looking for aliens. Here are some updates on the performance and progress. In summary, the upgraded telescope is performing just as hoped and is scanning the skies. But first, some background.

The OSETI telescope, whose construction was funded by the Planetary Society and its members, is operated in Harvard, Massachusetts by Harvard University Professor Paul Horowitz and his research group. It is the only optical all-sky SETI survey, scanning the skies every clear night, looking for billionth of a second laser pulses from distant extraterrestrials (none found yet, but wouldn’t that be a rather big discovery if they were).

Horowitz’s graduate student, Curtis Mead, completed his Ph.D. thesis “A Configurable Terasample-per-second Imaging System for Optical SETI” based on his development of the new OSETI telescope electronics system. Curtis reported, “The Advanced All-sky Optical SETI camera (AdvCam) is complete and has been operational since August, 2012. It has completely exceeded my expectations and works better than I could have hoped.”

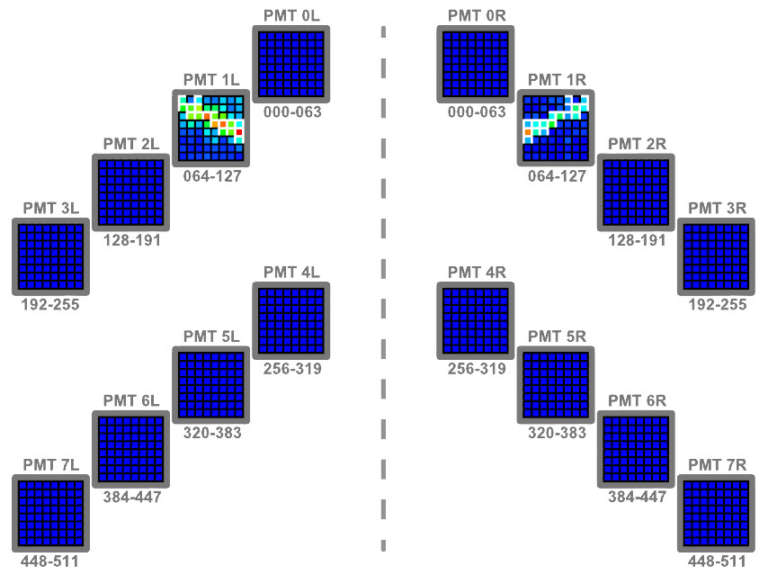

AdvCam, designed by Curtis, and funded in part by Planetary Society members, improved significantly upon the already impressive back end electronics of the telescope. The electronics analyze terabytes (trillions of bytes) of information every second. When there is a possible “pulse event” (spike in photons that could be from an ET alien signal, or from something much more mundane), AdvCam can record every pixel in the two 512 pixel arrays for a period before and after the pulse. Its predecessor could only record a much smaller sampling of pixels over a shorter time frame.

Why is the upgrade so exciting: because it allows the rapid distinguishing and removal of non-ET signals, specifically Cherenkov radiation, and airplane strobe lights. The Cherenkov radiation was particularly a problem. Cherenkov radiation is caused by cosmic ray particles hitting the atmosphere and creating a brief blue glow.

AdvCam also has extended the wavelength range being studied into the near-infrared, which is nice since we don’t know where ET will broadcast. The more wavelengths we watch, the more chance we will have of detecting the needle in a haystack signal.

Curtis reported:

The first observations with the Advanced All-sky Camera were performed on September 11th, 2012. As of March 31st, 2013, 174.4 hours of observations had been completed, covering 3,602 square degrees. Within these 174 hours, 318 coincidence events were recorded: eighteen of which are identified as Cherenkov light from cosmic ray induced extensive air showers, ~30 are traced to aircraft, and the rest are single-pixel, low-amplitude pulses caused by detector artifacts.

A little more detail, taken from Curtis’ Ph.D. thesis:

In general the coincidence events can be split into three broad categories: single pulses of a few nanoseconds that trigger multiple pixels, single pulses of a few nanoseconds that trigger single pixels, and events of microsecond duration consisting of many single photo-electron pulses. We believe these correspond, respectively, to cosmic rays, photomultiplier tube dark currents and photon pileup, and airplanes.

So, no ET discoveries, but the system is working as planned so we will be better able to find ET signals if they are there. AdvCam is doing its jobs: scanning the skies, analyzing the data, collecting the interesting stuff, and enabling the rapid sorting out of non-ET causes of “coincidence events.”

Help the Search: Contribute to Our OSETI Project

If you want to get a bit more into the electronics, some is presented in a bit more technical detail below, again from Curtis Mead (crank up your best Tim Allen technology grunting).

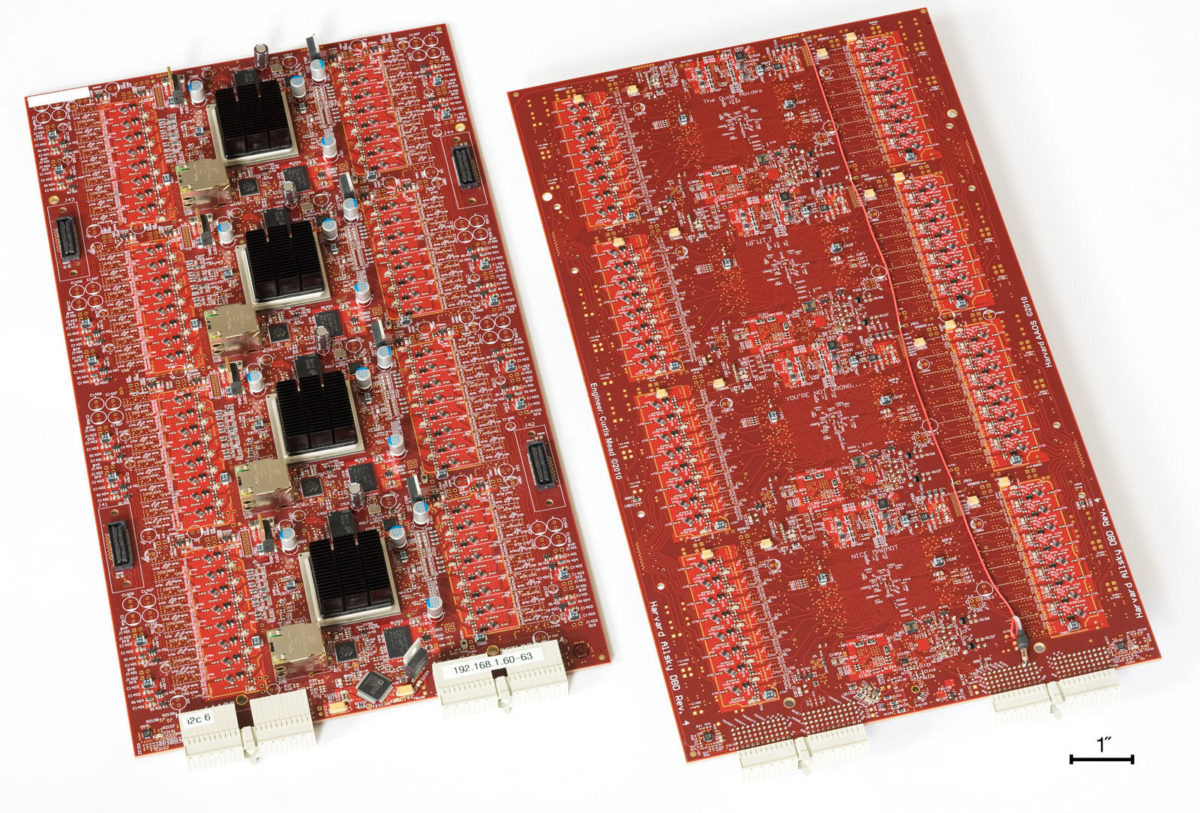

The finished camera electronics are able to sample pulse waveforms from our photomultiplier tube sensor array (1024 pixels, 300nm-900nm) at 1.5 Gsps (8 level, ~3-bit, 8k samples per channel) by using the trick of turning 8 LVDS input pairs into an 8-level flash ADC. As such (gigasample x 1k channel = terasample), my thesis is titled "A Configurable Terasample-per-second Imaging System for Optical SETI."

There are a few cute hardware tricks such as using a Spartan-6 as the coalescer for the trigger in/out signals for the 32 Virtex-5's. The trigger lines do double duty as serial terminal lines for the Microblaze processors on each Virtex during boot so that the bootloader and Linux boot messages can be debugged. All power is delivered by Vicor switching supplies outside of the camera body and regulated using low-dropout linear regulators on the FPGA boards to keep switching supply noise low. This resulted in some interesting power requirements (1.4V @ 80A regulated to 1V for V5 cores and 2.8V @ 80A regulated to 2.5V for V5 I/O) and satisfyingly thick 0 gauge power cables for the camera.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth