Stephen J. Pyne • Sep 25, 2013

Voyager: A Tribute

On 20 March 2013 a press release from the American Geophysical Union announced that Voyager 1 had broken through the heliosphere, the outer crust of the solar winds. Within hours the AGU retracted that claim and declared that the spacecraft had not punched through – yet. One measure (cosmic rays) suggested Voyager had pushed beyond the heliopause; another (magnetic field) that it still lagged. Instead, it was decided that Voyager, half in and half out, occupied a "new region of space."

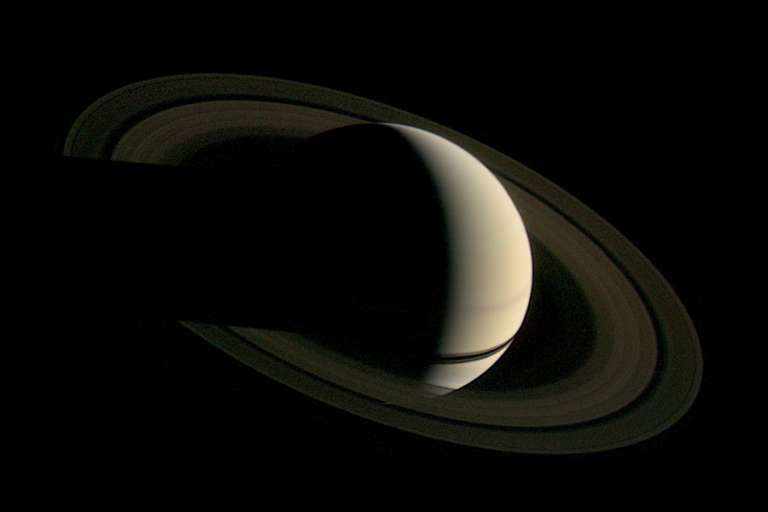

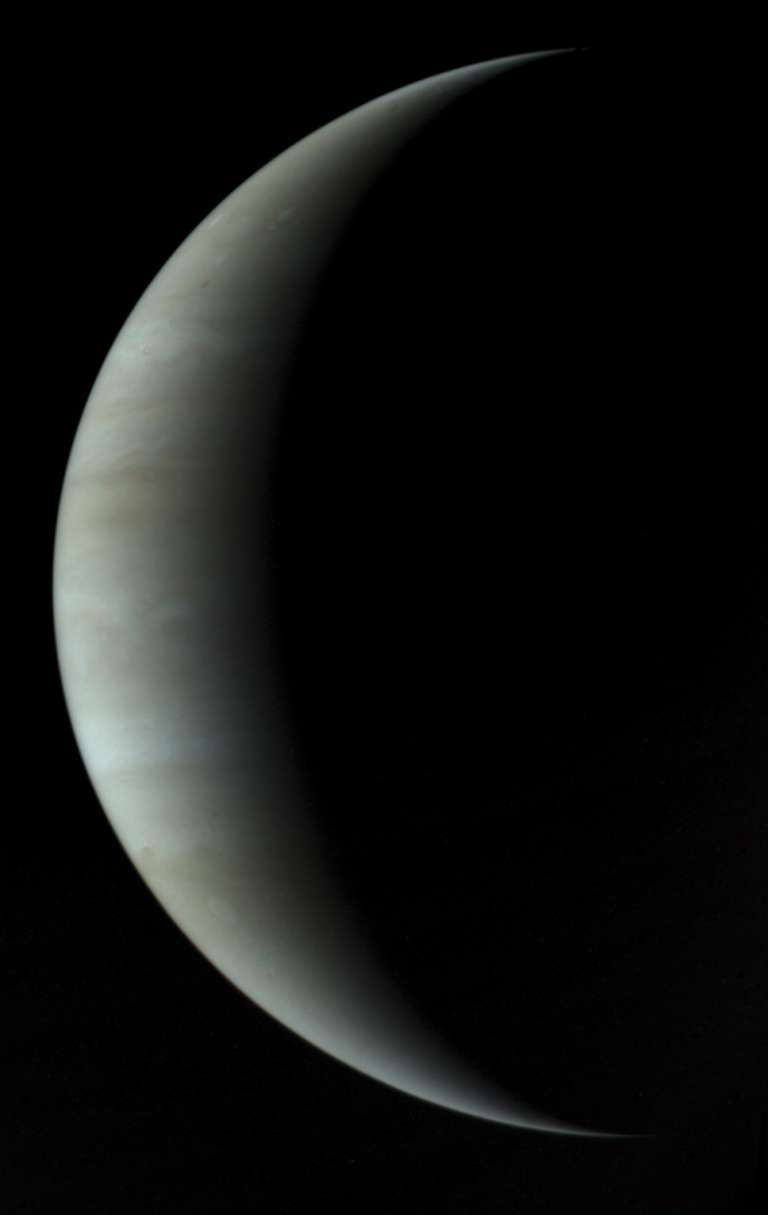

It was an odd phrase but an apt characterization, because that was where the Voyager mission has always been. One of its many alluring peculiarities is that it has looked back as much as it has looked forward. Two weeks after its 1977 launch Voyager 1 looked back to shoot the first image of the Earth and its Moon. On Valentine's Day, 1990 it looked back on the solar system and took a family portrait of six planets, including the famous "pale blue dot" that was Earth. When it turned its cameras back on Io, the inner moon of Jupiter, it captured a volcano in eruption. Its most radiant images of Saturn's rings came when it turned back over its shoulder, the rings backlit by the Sun.

Less well appreciated may be the way the Voyager twins have looked back on the history of exploration. Even as they are celebrated for racing forward - to the outer planets, to the heliopause, to interstellar space - many of their most dazzling discoveries were the offshoot of staring back at what they passed in their sling-shot fly-bys. Their trajectory is a triangulation of future and past, or what might be recalibrated as expectation and meditation. Mechanically, the twin spacecraft launched on a three-stage Titan Centaur rocket. Historically, what carried them to escape velocity were three great ages of discovery that began 600 years earlier.

The Voyagers were special when they launched. They have become more so thanks to their longevity, the breadth of their discoveries, the cultural payload they carried, and the sheer audacity of their quest.

Longevity. When they launched on 20 August and 5 September 1977, 20 years had passed since Sputnik. The Voyagers are now nearly 35 years old. Their single mission has spanned 64% of the space age. When they finally expire around 2025, they will have encompassed 71%. There is nothing else comparable. It's as though Vasco da Gama had embarked from Lisbon in 1498 and was still at sea 25 years after Magellan's Victoria had completed its circumnavigation. The spacecraft are on minimal power (there aren't many planets or moons to scan), but they continue to return critical data about the "new region of space" they occupy.

Breadth of discovery. The Voyagers were the second spacecraft to survey Jupiter and Saturn. They were the first to do so with a full panoply of instruments and to survey the giant planets' moons; and the first (and only) to visit Uranus and Neptune. They are the first to enter the heliopause and will be the first to exit and pass into interstellar space. They discovered 26 unknown moons. They found volcanoes on Io, warmed by the gravitational tides of Jupiter, and they unveiled geysers on Triton, among the coldest object in the solar system. They revealed that the outer planets hold a menagerie of worlds far more active and varied than anyone had imagined. They are defining the blustery border of bow shock, where the solar and interstellar winds churn in filmy swirls against each other. They trekked through the entirety of the planets. "You only explore the solar system for the first time once," Larry Soderblom, one of the mission's two geologists noted. "Voyager did that."

Cultural payload. Voyager's Grand Tour was a big-science expedition. It followed Viking's mission to Mars and was expected to yield to an ever-escalating corps of robotic discovery to the planets and eventually to the stars. The budget-sucking space shuttle killed that vision. Then the Challenger blew up on launch, and the Voyagers became for a decade the only show in the heavens. They carried the program and whatever aspirations it held. They also carried, one each, a gold-plated phonograph record with the sights and sounds of Earth, along with greetings in 55 languages, nominally to explain to an alien intelligence who might chance upon it where the spacecraft came from, but what in reality spoke to what we believed was best about ourselves. The odds of an alien Other decoding the record is astronomically tiny; but the message was noted by millions of Earthlings.

The Voyager twins began as machines crafted to do science. As they pass through the veil, they are assuming the quality of a vision quest because more than data, more than images, more than stories of broken hardware and software glitches and ingenious workarounds, more than sheer endurance, the Voyagers have been a journey. Its cultural payload is what distinguishes it from adventuring; its trek is what distinguishes it from space science. The Hubble space telescope has, through relentless imaging and clever software, discovered more moons than the Voyagers; but it has no narrative. The Voyagers tap into a deep psyche of questing. Yet in one critical way, they differ from the classic hero's trek. They won't return. Instead, they carry their home with them in the form of the golden records. Narrative closure for their saga acquires a self-referential loop. The Voyagers are explorers of modernism.

They are, that is, both of a past and a present – on the edge of exploration history as well as of explored geography. While the voyage of discovery that put to sea in the latter 15th century has been continuous, it has not been constant. It shows crests and troughs. It began explosively, unfurled with the Renaissance, then stalled as discovery settled into trade; by the early 18th century exploring was banal, ignored, or satirized. It renewed as northern Europe took up imperialism and valenced the voyage of discovery to the Enlightenment. Naturalists displaced missionaries; new genera of flora and fauna replaced cinnamon and pepper as precious cargos. Then exploration ran out of continents and ran out of luck on the ice sheets; science looked to atoms and genes; and modernism, like a software virus, began rewriting high culture. Intellectuals preferred to follow Freud into the unconscious rather than Stanley into the Congo. Modernist art had little kinship with geographic discovery.

Exploring revived in the postwar era, pivoting on Antarctica, while submersibles and rockets opened the deep oceans and the solar system to another great age of discovery. This new age, the third, ours, is yet young. Its hardware and software are often out of sync, as we struggle to find ways to mesh our extraordinary technology with a culture of modernism. The robot has assumed the mantle of explorer; in the absence of an Other, the encounter becomes an exercise in self-discovery or immersion in the robots. Project teams speak, for example, of “inhabiting” the Mars Exploring Robots, Spirit and Opportunity. Such novelties are innovations in the long chronicle of geographic discovery. Yet they are lineal descendants, or reincarnated avatars of Pedro Cabral, Charles Sturt, and John Wesley Powell, who also had to adapt voyaging to transport the baggage of their day and navigate by the cultural constellations of their times. Each age had its grand gesture, an expedition that captured the character and domains of discovery peculiar to its circumstances. For the Great Voyages of the Renaissance it was surely the circumnavigation of the world ocean by the Victoria, captained by Ferdinand Magellan until, in the spirit of the age, he died in a senseless fit of militaristic hubris. For the renewed exploration of the Enlightenment, it was the traverse of a continent, a cross-section of natural history of the sort pioneered by Alexander von Humboldt before the baton passed to Lewis & Clark, Burke and Wills, Alexander Mackenzie, Henry Stanley, and their ilk.

What the equivalent for the third age will be is unclear – we're still in early days. Considered as exploration, most of the activity will occur in Earth's deep oceans, and it may be that historians will consider the cumulative adventures of the submersible Alvin as the most representative emblem of the era. But the story of Alvin is a biography rather than the narrative of a quest. What the age begs for is the equivalent of a circumnavigation of the world-circling oceanic abyss or a traverse of the solar system, an expedition outfitted not just to adventure and survive but to inquire beyond the realm of the possible. Which is why my vote goes to Voyager. More munificently than any other mission Voyager speaks to what exploration means in our times, and why it matters, and how we might understand our age's awkward alloy of innovation and historical inheritance. It triangulates our place in the unfolding trajectory and "new regions" of the third age. And now Voyager 1 has trekked beyond the heliosphere.

Voyager the curious, Voyager the bold, Voyager the tenacious, Voyager the indomitable. As they pass beyond the veil of the heliopause, the Voyagers will come as close to an apotheosis as human contrivances might manage.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth