Bill Dunford • Aug 20, 2013

A Map of the Evening Star

“A map says to you, Read me carefully, follow me closely, doubt me not. I am the Earth in the palm of your hand.”

—Beryl Markham

Beryl Markham knew about maps. She was a pilot, author and racehorse trainer, most famous for being the first woman to fly alone across the Atlantic from east to west, an adventure she recounted in her memoir, West with the Night. As an aviator, she would have been very familiar with the sight of the evening and morning star—the planet Venus—in the sky.

What she didn't know was that just a few years after her death, a robotic spacecraft would circle Venus, fire powerful bursts of radar through its veil of clouds, and begin to image the strange world's oven-hot surface. Those radar images would allow a new breed of explorer to make a new generation of maps, including one chart in particular that marks the location of a crater named Markham.

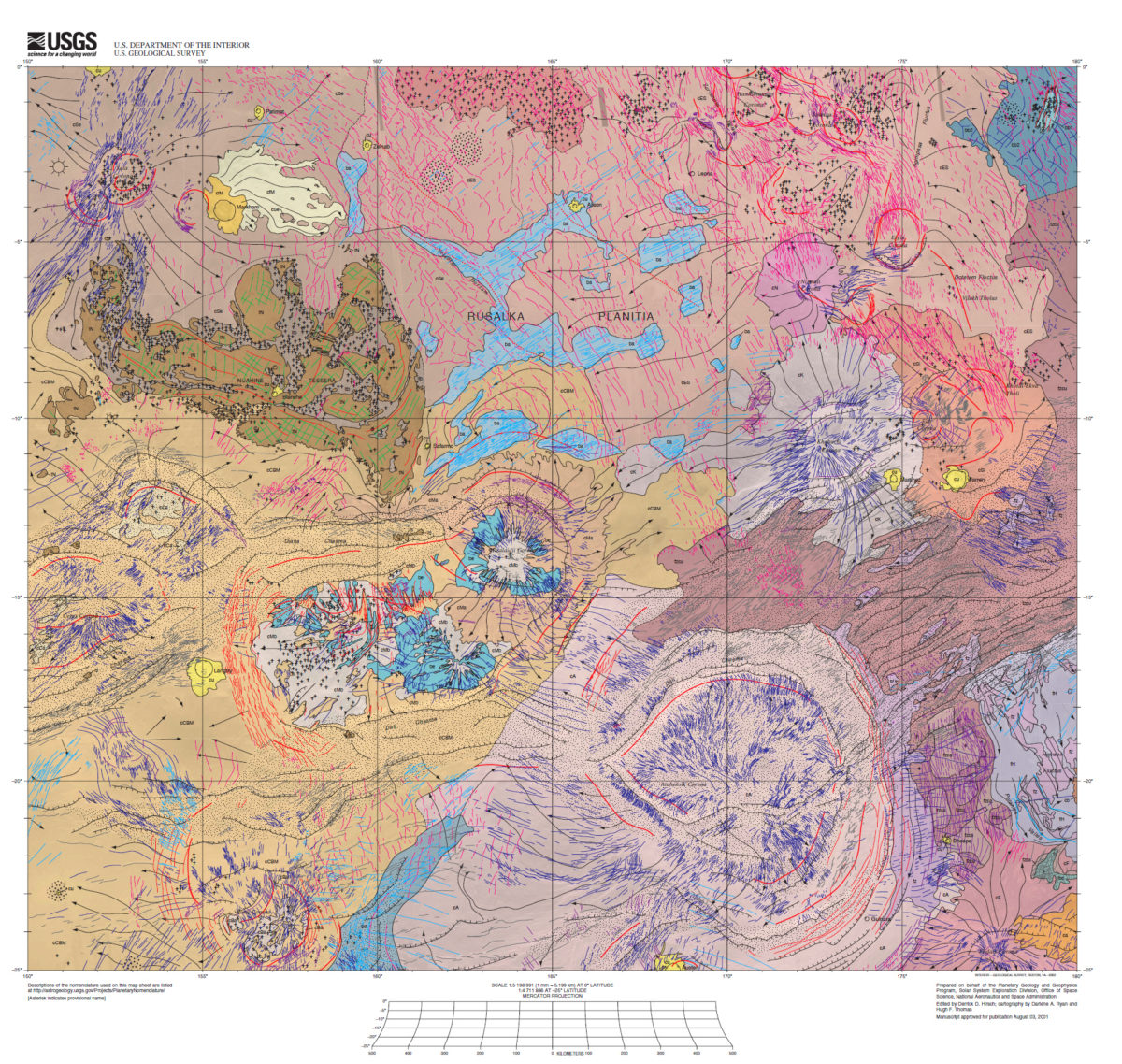

I like maps of the planets beyond Earth. They're both informative and beautiful. They embody craftsmanship, precision, and art. The US Geological Survey actually produces wall-sized paper maps of nearly every body in the Solar System. I love how these maps allow a mental line to be drawn: from a 17th-century sea captain poring over charts in his cabin as he explores new coastlines, all the way to a 21st-century post-doctoral student in front of a computer monitor, discussing potential landing sites on Europa with her peers on multiple continents in real time.

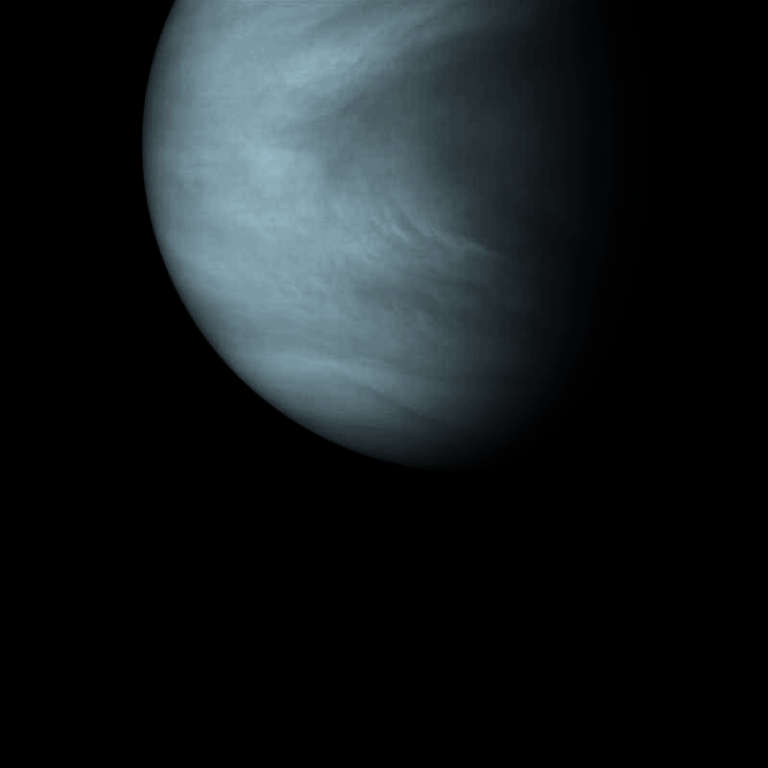

Take as an example one map in particular, a geological map of the Diana Chasma quadrangle of Venus. Before the space age, the planet Venus was a blank sphere, continuously shrouded in thick layers of clouds. (Many people assumed this meant the planet was covered in steamy jungle. You probably know the reality is starker: the clouds created a runaway greenhouse effect that rendered the surface the hottest in the Solar System, a hell of acidic skies and temperatures in excess of 460 degrees celsius.)

Even to most passing spacecraft, the view of Venus is nothing but cloud tops.

Several Soviet craft dared a landing. They only survived a few minutes. The key to piercing the veil of Venus planet-wide turns out to be radar. Scientists learned a lot using facilities like the giant antenna at the Arecibo Observatory to bounce radar signals through the clouds, off the surface, and back to Earth for analysis.

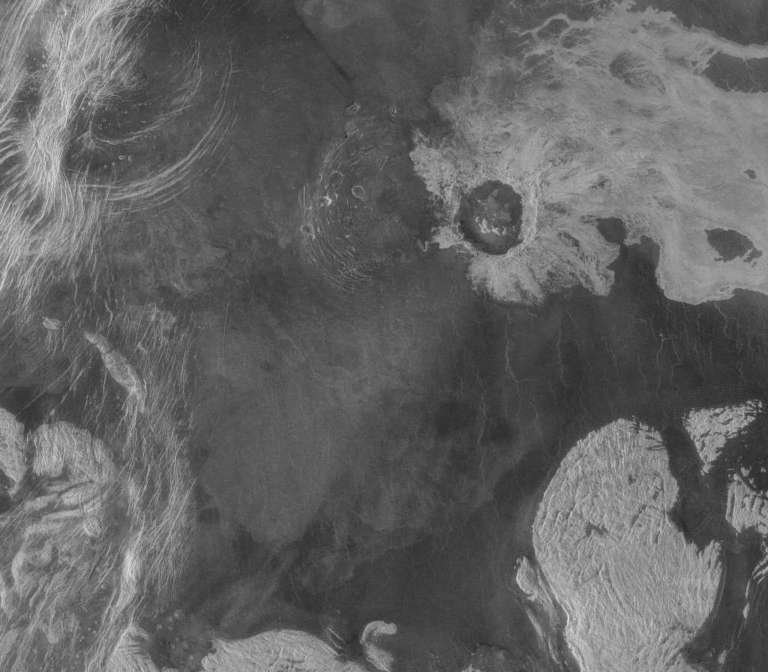

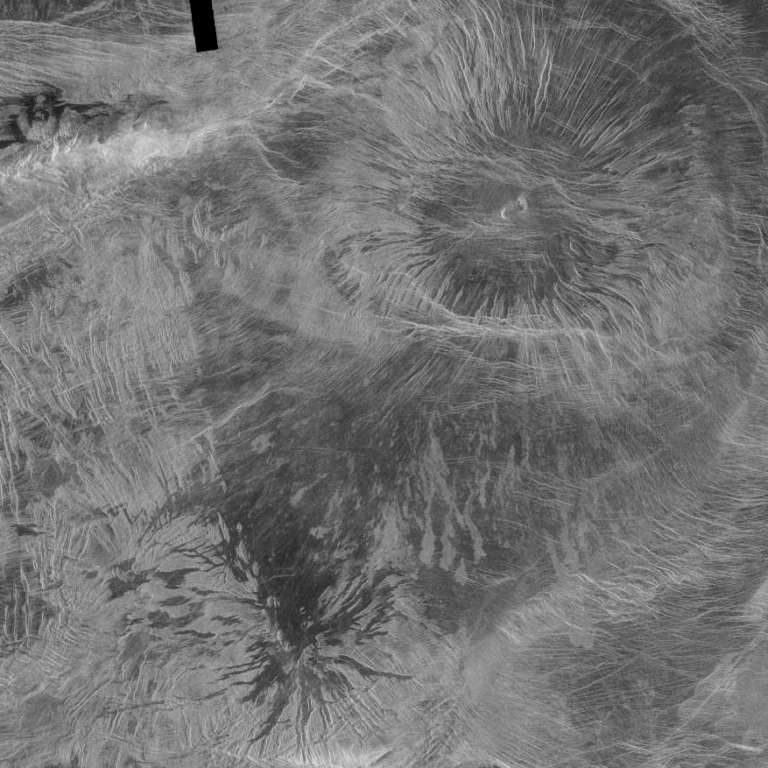

Even better, in the 1990s an orbiter named Magellan took up its station at the second planet. It carried a synthetic aperture radar system to map the surface. Radar imaging and altimetric and radiometric mapping covered 98 percent of the planet, with radar resolution of about 120 meters. This allowed Magellan to create lovely images of the landscape, like this one of the area surrounding Markham Crater. Venus explorers think a violent impact dug the crater, and either melted or released molten rock that flowed downhill.

In this view, we can see some of the planet's extremes. There are tall raised areas like Miralaidji Corona, which is an example of where hot magma welled up near the surface, creating radial fractures and causing lava to spill out across the plains. But in this same shot we can see part of Diana Chasma, a 900-kilometer-long trough that includes some of the deepest points on the globe. This is among the steepest terrain on Venus, with altitudes ranging from –2.5 to 4.7 km. In some places the slopes incline more than 30 degrees.

All this exploration yields more than pretty pictures. By analyzing data from the full suite of instruments on board Magellan, along with information from other orbiters, landers, and Earth-bound observers, scientists can begin to piece together the geology—and thus the history—of Venus as a whole. All without risking boots (smoking, melted boots) on the ground.

One product of the data collection and painstaking analysis is this gorgeous map of the Diana Quadrangle, including Markham Crater and Miralaidji Corona, along with many other craters, cliffs, and fissures.

You can see more detail by clicking the image, or get the complete map, key, and other notes on the USGS site.

There is still so much to explore, so many places where the maps are incomplete. Pioneering aviator Beryl Markham wrote that, "I learned to wander. I learned what every dreaming child needs to know—that no horizon is so far that you cannot get above it or beyond it."

But none of this will be easy. She also warned, “We fly, but we have not 'conquered' the air. Nature presides in all her dignity, permitting us the study and the use of such of her forces as we may understand. It is when we presume to intimacy, having been granted only tolerance, that the harsh stick falls across our impudent knuckles and we rub the pain, staring upward, startled by our ignorance.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth