Bill Dunford • Jul 23, 2013

Jani Radebaugh, Titan Explorer

One of the most important things about robotic space exploration is that it isn't really robotic. It's human exploration. Sure, the machines are the ones that fly through the vacuum, the radiation, the fiery re-entries, the freezing nights and lethal sunrises. But in every case, these robotic spacecraft were conceived, built, and flown by people. The scientists and engineers and artists behind these missions are the heirs of Benjamin Franklin and his kite. They've traded string and key for rocket fire and radar, but like Franklin they're just people who want to know what's up there. And they want to get a closer look--even though they can't leave the ground themselves.

I've been lucky enough to meet many members of deep space mission teams, and it's always a pleasure. The common denominator is an enthusiasm for discovery that is genuinely contagious.

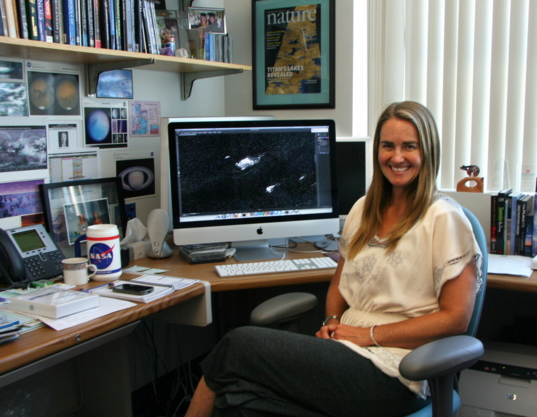

Dr. Jani Radebaugh is no exception. She's a planetary scientist who has worked on several missions, including the Galileo probe that explored the Jupiter system. Her geologic field studies on Earth have taken her to many corners of the world, and even to Tatooine. She now collaborates with the team that uses the radar instrument on board Cassini to study the planet-like moon Titan. When I met her last week in her office on the campus of Brigham Young University, the first thing she wanted to do was show me her computer screen--where there was a brand-new image of the surface of another world. She traced the newly revealed landforms with her finger, pointing out some unexpected features with obvious excitement. We took a moment to relish the fact that we were among the first human beings to ever see that place.

Bill Dunford

Jani Radebaugh

Dr. Jani Radebaugh, planetary scientist.

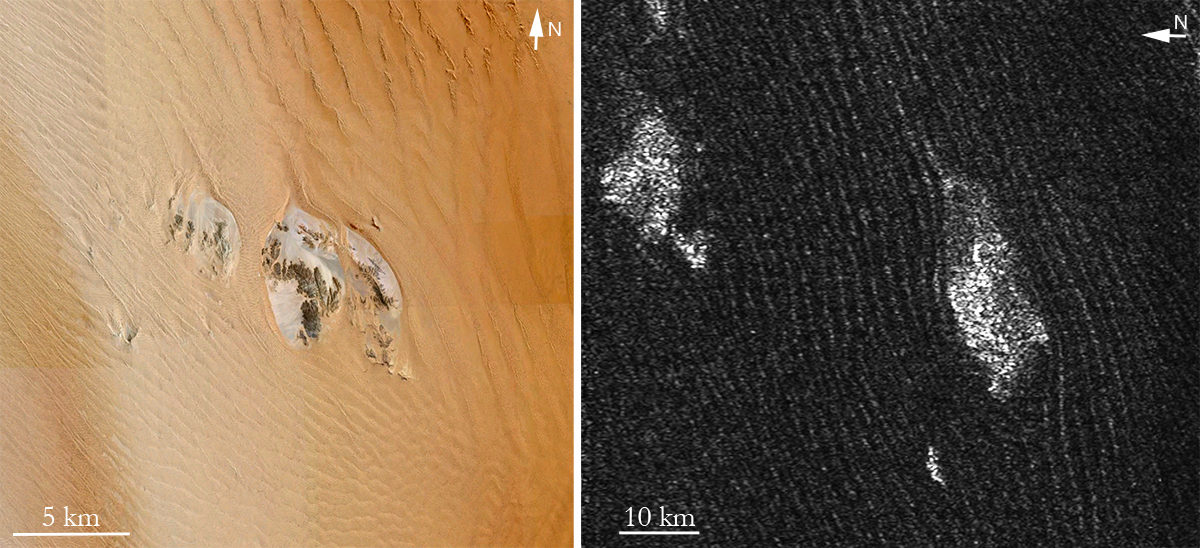

But what captures most of Radebaugh's attention these days are the dunes seas of Titan. The cloud-wrapped moon is famous for its exotic 'water cycle' of liquid methane. It actually rains methane and ethane. There are even rivers, dried lake beds, flooded valleys, and entire seas of methane that change with the seasons. But Titan's dry dunes are important, too, and what makes them so is their decidedly un-exotic nature. Thanks to Cassini's radar it's now possible to study Titan's vast sand seas in detail. It turns out some of the dunes (even though they're made of organics that snow out of the orange clouds) are almost exactly the same size and shape as similar kinds of features on Earth.

For example, here's a comparison of dunes surrounding an obstacle as found in Namibia and in Titan's Belet sand sea.

Dunes act as weather vanes, with much to reveal about the strength and duration of local winds, which of course can lead to insights about weather and climate on a global scale. And that goes for Earth as well as Titan.

In fact, Radebaugh says this opportunity to compare and contrast conditions on other worlds with our own is one of the most valuable contributions of space exploration. Whether it's the hellish greenhouse effect on Venus or the way sand seas can swallow the surrounding countryside, there is much to be learned about our own planet by studying others.

Another of Radebaugh's favorites, whether on Earth or in space, is volcanoes. She has risked close encounters with active eruptions around the world. Ask her where she would go if she could safely stand in any spot in the entire solar system, and she'll tell you it's the edge of Pele, an active volcano on Jupiter's moon Io. There, a jet of gas rises 450 kilometers into the sky above a huge, churning lake of lava. If she had the chance, she'd gather a scoop to find out whether it contained material from deep in the moon's mantle.

Bill Dunford

Volcanoes on Earth and Io

Top: Jani Radebaugh shows off a painting of Loki Patera on Jupiter's moon Io by Michael Carroll. Bottom: a lava lake in Ethiopia, photographed by Radebaugh, that shares some characteristics with Io’s volcanic features.Studying the worlds in the Solar System really does require knowledge from a wide variety of disciplines: geology, meteorology, astronomy, even biology. This is why Radebaugh finds planetary science so compelling—it’s a sort of pinnacle of the sciences.

What troubles her and many other explorers is the looming threat of exploration "going dark" in the outer Solar System. Cassini will plunge into Saturn's atmosphere in 2017. At that moment, the radar team will have imaged no more than 60% of Titan's surface. Much more ominously, no more missions to Saturn or any other outer planet are even in the serious planning stages right now.

Still, Radebaugh holds out hope. She notes that while the budget situation looks particularly grim now, things can and will turn around with one key ingredient: public support. She says that citizens contacting their elected representatives in general, and The Planetary Society's organized efforts in particular, have a major impact on how many missions ultimately will fly and what new worlds we will explore.

Meanwhile, she says, there are plenty of exciting frontiers being pushed back during the next few years. Her favorites: the Dawn mission to the giant asteroid Ceres and the Osiris Rex mission to retrieve a sample from the asteroid Benu and return it to Earth. This is not to forget the ongoing adventures of Cassini, which will have a chance to observe Titan's northern summer solstice. What will happen to the dunes as the weather changes? And what about the methane seas—will they shrink in the North and grow in the South? The intrepid spacecraft will also fly right between the planet and the rings before its swan song into Saturn's storms.

But she says the most exciting, interesting, variable, and challenging destination of all is still the Earth.

“If we lived somewhere else in the Solar System, we would be dying to go here,” she says. “There is still so much to learn.”

Bill Dunford

Lots to Explore

The office of a planetary scientist contains plenty to examine.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth