Casey Dreier • Jun 19, 2013

If we started today, how long would it take to get to Mars? With this budget, never.

Congressman Bill Posey (R-FL) leaned forward as he asked his question of the House Science Committee's guest panel, "If we started today, how long would it take to land a human on Mars?"

Tom Young, on the panel, laughed a bit and asked, "With today's budget for NASA or the Apollo-era budget?"

"Both," said Posey.

"With the current budget," answered Young, "probably never. With Apollo-era, maybe by 2025."

This is the searing problem at the core of NASA today: what is the agency's mission, especially regarding human spaceflight? If it's to land a human on Mars, why is Congress and the Administration effectively making it impossible? If it's not, then what is NASA's mission?

The House Science Committee today held a hearing to discuss this very topic, which is partially addressed in their newly proposed draft of the NASA Authorization Act, which sets policy for the space agency as well as funding caps. This bill would not actually fund NASA, just limit how much could be spent. It also states the general direction of the agency and other expectations for individual programs, reporting, etc.

In that regard, it's a rough bill. According to a summary released to SpaceNews, the committee would approve a mere $16.8 billion to NASA for the next two years, maintaining its current sequester amount which is about $1 billion less per year than requested by the White House, and $3 billion less than what was approved in the previous authorization bill in 2010.

"The stark reality is that if we fail to reform mandatory spending, discretionary funding for space, science, and research will continue to shrink," said Rep. Steven Palazzo (R-MS), Chairman of the Space Subcommittee.

What's he talking about? Well, take a look at the animation below. It shows the percentage of the U.S. budget devoted to "mandatory" (i.e. dictated by law and not subject to yearly congressional approval) in gray and the rest of the U.S. budget in red (defense) and blue (everything else). Note how the colored parts shrink over time:

Mandatory spending tends to be popular and politically very difficult to alter. Think about recent debates regarding Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare for examples.

But, as the graph shows, and what Rep. Palazzo was talking about, is that this growth will crowd out other spending if Congress intends to actually reduce overall spending. And discretionary spending cuts affect two areas that we care very much about: space exploration and scientific research.

The two witnesses at the hearing, Dr. Steve Squyres from Cornell University and former NASA Goddard Director A. Thomas Young spoke repeatedly about the consequences of diminishing budgets but stable (or increased) commitments.

"NASA is being asked to do too much with too little. Unless program content can be matched to budget, the result will be wasted effort and delay," said Squyres.

There was clear tension between some of the Republican and Democratic members on the committee.

"I am concerned however, with several aspects of this draft bill, and I question whether, in the end, this draft will serve to ensure our nation's hard-earned leadership in space and all the inspiration, discovery, international standing, and economic benefits that such leadership brings," said Rep. Donna Edwards (D-MD), the ranking Democratic member on the Space subcommittee.

This was echoed by Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX), the ranking Democratic member on the Science committee, "I regret to say that if enacted, it would not help NASA meet the challenges facing the agency. In short, it is a missed opportunity to position NASA for excellence, and it's a bill that if enacted would lead to the erosion of the capabilities that have made NASA such a positive force for progress."

Additional criticisms from Dr. Squyres and Mr. Young focused on the crippling cuts proposed to Earth Science, concern as to whether Congress was micro-managing the agency by inserting arbitrary requirements for lunar exploration to the bill, as well as questioning the necessity of lunar exploration to begin with.

Neither witness was a supporter of NASA's Asteroid Retrieval Mission, which would redirect a small asteroid into the vicinity of the Moon for future human exploration. The House NASA Authorization bill explicitly forbids NASA to pursue such a mission.

NASA is standing at a crossroads: there is so much possibility for our future in space, but funding levels, inner conflict, and a lack of direction and leadership all stand in the way of this great era of exploration. The House has made their intentions clear, which is that NASA should return to the Moon and that NASA will have less money to work with when they do so. The Planetary Society considers this an ill-fated and expensive diversion from the ultimate goal of exploring Mars (see our 2008 roadmap for human spaceflight) and we are very concerned about funding levels for NASA in general.

The Senate has yet to weigh in with their draft authorization bill, which will come out in the next few weeks. Expect it to fund NASA at a higher level and include funding approval for the asteroid retrieval mission, among other likely differences.

These two bills will have to compromise on some level. But their differences are great and Congress has not shown much of a willingness to work together lately. One hopes that NASA is still the bipartisan program that it has been in the past, uniting those with disparate beliefs with a common goal of exploration, scientific discovery, and hope for the future.

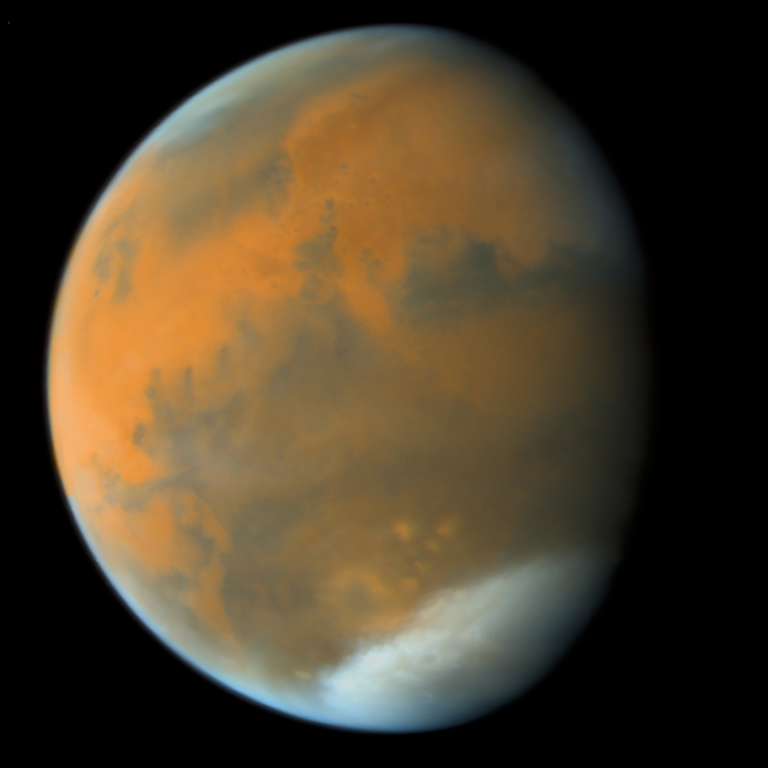

Maybe then NASA will have its singular goal, and maybe then we will start down the real road that will put humans on Mars. Until then, our robotic emissaries wait for us, rolling daily over frigid landscapes seemingly devoid of life, human or otherwise.

Stray observations:

- Rep. Mo Brooks (R-AL) threatened to vote against the bill unless more funding is given to the Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket, which just happens to be constructed in his district. It's approved for $1.4 billion in this bill, which is more than every other scientific program within NASA except for Planetary Science (which is approved at $1.5 billion).

- Speaking of Rep. Brooks, he read a letter from former NASA Administrator Mike Griffin excoriating current funding levels for SLS. Dr. Griffin is a big supporter of a return to the Moon and pushed very hard to ensure a future for the ill-fated "Constellation" program when he was Administrator. When Young replied that there should be an independent cost analysis of the program to determine proper funding levels, Rep. Brooks responded by saying that's exactly what the very not-independent statemement by Dr. Griffin was doing, very ironically emphasizing Young's argument.

- We've heard that there was little-to-no Democratic input on this bill, which was reflected in the general attitude taken by the minority members on the committee.

- Squyres did commend them for rejecting the proposed restructuring of NASA's education and outreach programs, something we haven't talked much about, but is covered in detail here.

- Another positive comment from both witnesses was regarding the bill's requirement for NASA to develop a roadmap for human missions to Mars given the capabilities of the SLS and Orion.

- No discussion about the proposed six-year term for the NASA Administrator. Strange, since it's a pretty big change in the way things work. Does this mean no one is taking it seriously? The White House would take a dim view on accepting a loss of its ability to appoint their own people to manage federal agencies.

- Not long after this committee hearing, Senator Bill Nelson (D-FL) said that the Senate would not approve a NASA authorization at $16.8 billion as proposed by the House, it would "put NASA into the ditch." So expect this to be the first step in a long process.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth