Bill Dunford • Apr 29, 2013

Dark No More: Exploring the Far Side of the Moon

The first human beings to see the "dark" side of the moon were not astronauts. As everyone from grade school children to Pink Floyd can tell you, there is no dark side of the moon, really--just the far side that is forever turned away from the Earth. During all history, while the familiar man-in-the-moon side was observed and charted and depicted in art and song, the far side remained a total mystery.

That changed in October of 1959, when the Soviet Union dispatched a small probe called Luna 3. The spacecraft was in some ways simple by today's standards, but it carried a remarkably ambitious set of machinery. Cameras that were pointed toward the moon exposed rolls of film, which were automatically developed right on board the spacecraft, then scanned so the electronic information could be beamed back to Earth by radio. The team working on that mission included the first people to see the grainy images that revealed the far side for the first time.

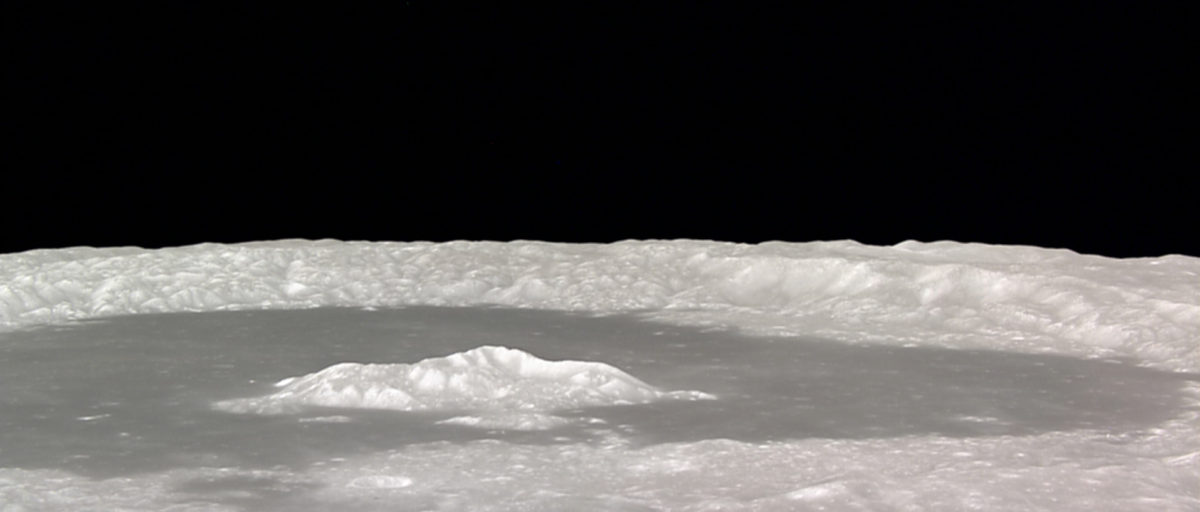

People have been sending robotic spacecraft back to the moon more or less ever since. Not surprisingly, with advancing technology the view has cleared up a bit. One of the most striking features to be added to the charts of the lunar far side is Tsiolkovsky Crater. This 185km-wide impact crater stands out because it enfolds a central peak rising over a slate-dark sea of solidified lava. The Japanese orbiter Kaguya captured some nice views with its HDTV camera as it glided silently over the scene.

Kaguya was able to show the crater in detail, including sites that were once considered for human landings during the late Apollo era.

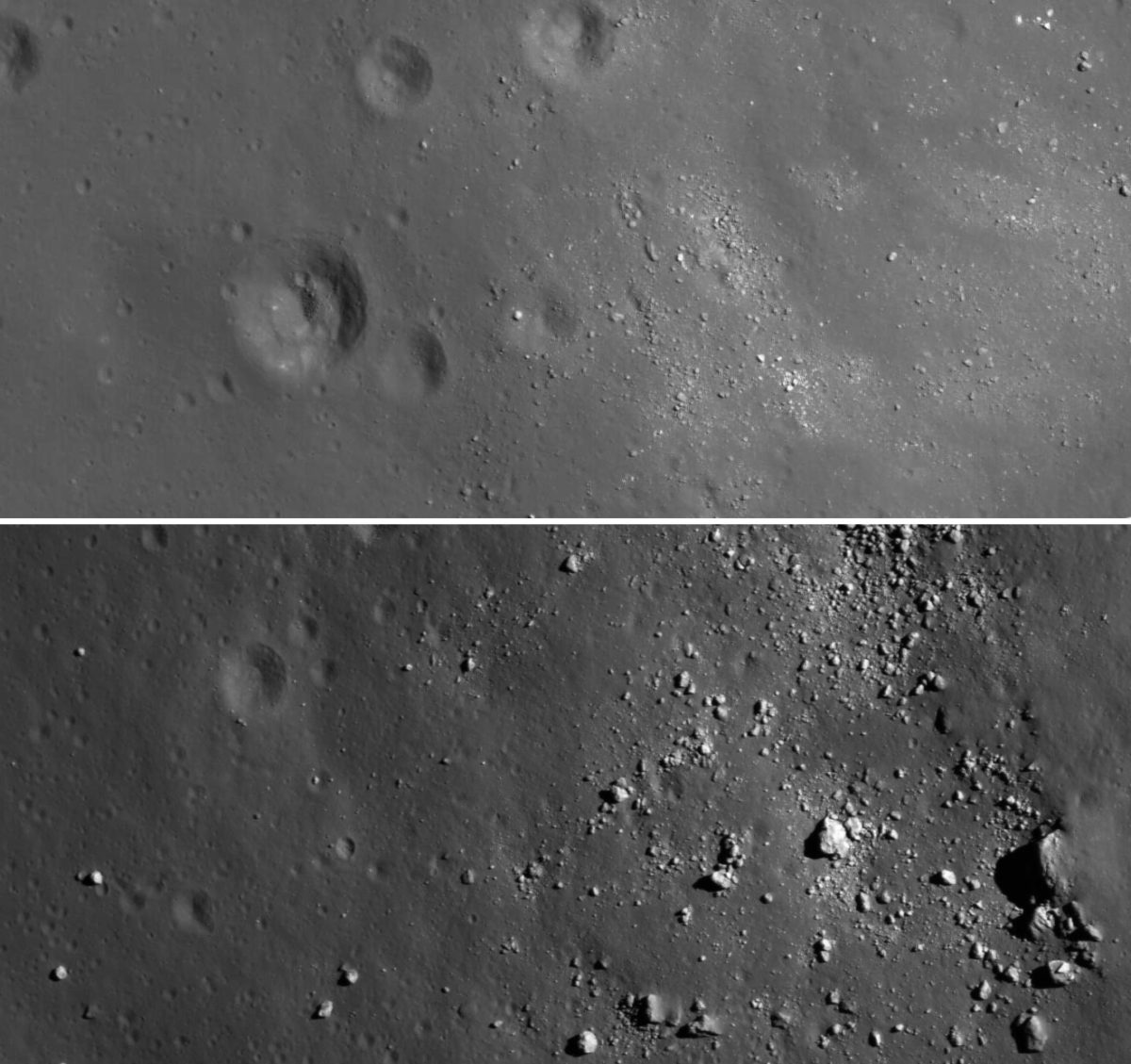

Today, there's an even more powerful orbiting platform flying day and night over the moon. The high-resolution cameras on board the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter are so sharp-eyed they can make out features smaller than a meter across.

In a few short generations, we've gone from a complete blank spot on the map, to wide surveys, to close-ups so narrow that we can see individual rocks.

Someday astronauts will probably make their way across this stark, exotic landscape on foot. When they do, they will surely rely in part on the maps we're making today with our intrepid space robots.

Thanks to Don Mitchell for this excellent collection of Soviet lunar probe history.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth