Casey Dreier • Sep 26, 2012

NASA's New Direction For Mars (Maybe)

On Tuesday, Sept 25th, the Mars Program Planning Group (MPPG) presented to the public its recommendations for the next decade of Mars exploration. What we saw were multiple mission plans straining to exist in the brutal new cost cap from the FY13 budget, pushed far into the future.

I ended up writing a lot of background for this post, which can be interesting, but may be a little much for people. Click here to get to the meat of the proposal.

Let's quickly break down what, exactly, we're talking about here with the MPPG, NASA's Mars Exploration Program, and how this fits into NASA.

NASA's funding is allocated into separate programs and divisions within the agency. Some goes to human space flight, some goes to running NASA field facilities around the country, and some goes to scientific research. The science division referred to as the SMD (Science Mission Directorate) and is led by the Hubble-repairing astronaut hero John Grunsfeld. The SMD is responsible for all scientific exploration/funding at NASA, and it itself is broken up into five different sections: Heliophysics, Astrophysics, Earth Science, The James Webb Space Telescope, and our friend, Planetary Sciences.

Planetary Sciences is responsible for all missions and research funding for bodies in the solar system that are not the Sun or the Earth. This division was funded at around $1.5 billion/yr (~8% of NASA's total) but now faces cuts of about 21% from the proposed 2013 budget.

But we're not done! Mars represents such a large focus of our exploration resources over the past few decades that there exists within Planetary Science a program devoted to funding a cohesive set of Mars missions. This is the aptly named Mars Exploration Program, which is responsible for all of the recent missions: Mars Global Surveyor, Odyssey, Spirit & Opportunity, MRO, Phoenix, and Curiosity. The MEP gets its own funding line in the budget, which allows it to create its own mission proposals and goals. Having budgetary control and long-term goals means that the MEP (and therefore NASA) is able to very effectively implement a suite of missions that build on top of each other, feeding back information from one mission to the next, supporting R&D into technologies needed in future missions, and creating proper communications relays for getting data back from the red planet. Dr. Scott Hubbard, who helped formulate the current MEP, described it as modeled after the Apollo program in the 60s.

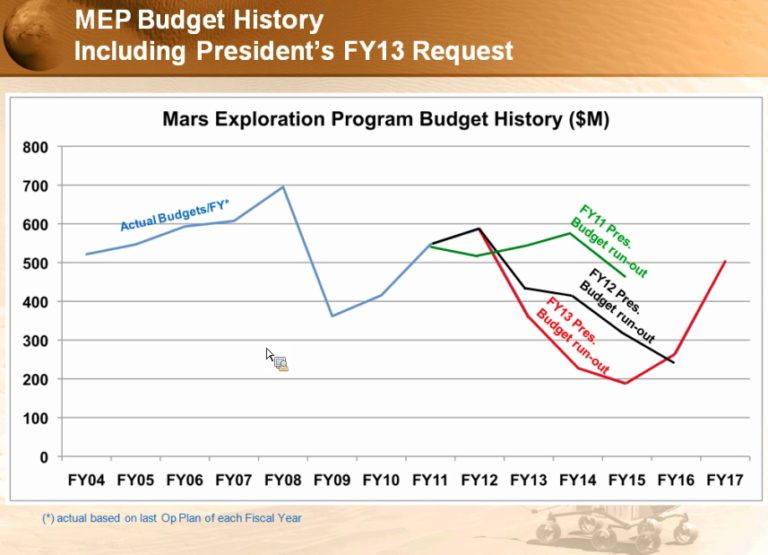

The great success of NASA's Mars program was rewarded with a proposed 40% cut next year, with further cuts in 2014 and 2015. Here's this is in graph form (the red line is the latest budget proposal):

Because of these drastic cuts to the Mars program, NASA couldn't continue with the next big missions, a joint European-NASA project called ExoMars and the Trace-Gas Orbiter.

The Office of Management and Budget forced NASA to pull out from these missions earlier this year, and the Mars Program Planning Group was created to reformulate the future of the Mars program given the harsh budgetary constraints seen above. On Tuesday, Sept. 25th, the Chair of the MPPG, Orlando Figueroa, presented the initial results of their work to the NRC's Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Science (CAPS) meeting, followed by a press conference.

The MPPG hasn't so much come up with a recommendation but laid for a set of options that will start NASA on the path to returning a sample to Earth from Mars. As such, there was no one answer to "what's the future of Mars exploration?" We do know a few things, though:

- If the budget increases, the earliest possible mission would be in 2018 and would be a "caching rover."

- If the budget does not increase, we could send an orbiter in 2018, and maybe a rover 2020.

- All landed missions are rovers that would search and cache soil and rock samples.

- One program option is sending a fleet of MER-style rovers to three different locations to maximize the likelihood of good samples.

- The other program option would be to send a single MSL-style rover.

- Most of these would require a separate mission that would land nearby, retrieve the samples, and launch them into Martian orbit.

- One potential mission includes the launcher component, but cost is not fully estimated.

- Once in the samples are in orbit, it would have it dock with a robotic Earth-return vehicle or be picked up by Astronauts in the 2030s.

- Any combination of proposals would not return samples until after 2024, under the best of conditions.

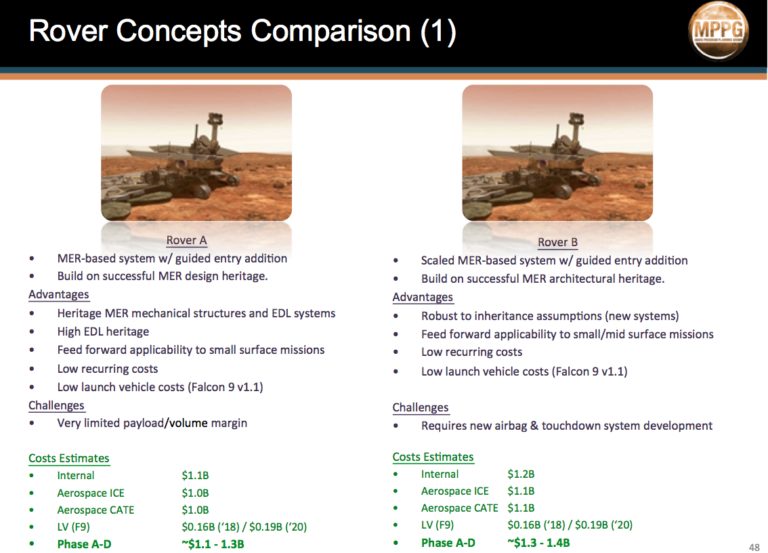

The MPPG looked a multiple different mission concepts. They break down into two variants in order to save money: a MER-derived rover and an MSL-derived rover. Here's the cost estimates for the MER-derived version:

From the report, it looks like these MER-style rovers would use the airbag landing system, but with the advanced guided-entry avionics used by Curiosity. A very cool idea presented in the report was sending three (!!!) MER-style rovers to three different sites. Based on the scientific findings at each site, the community would determine the best samples and send a retrieval mission to one of the rovers. Beyond the cool-factor of having three rovers running around the surface at once, the amount of science you could do in situ would be huge.

Another cool thing to note is that they're using SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket to launch the MER-style rovers as a method of reducing cost.

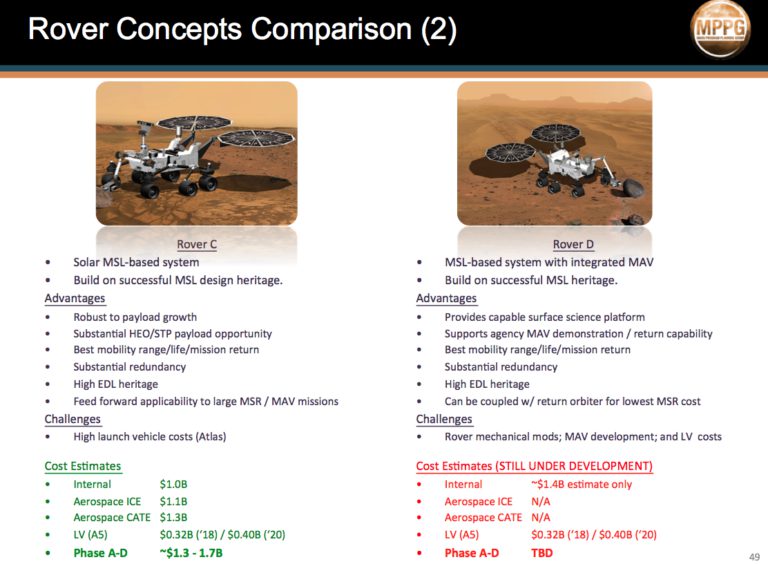

The MSL-derived concept would send just one rover to a pre-selected site to gather samples. It would use the same EDL system as Curiosity, but be solar-powered, since Plutonium is so scarce (and pricey):

Note that the Rover D concept includes the rocket to launch samples back up into orbit around Mars. Note also that they haven't finished the cost estimates for this mission. It represents untried technology and is therefore hard to estimate accurately. It would likely be higher than the other landers (though it would have an overall lower program cost since you wouldn't need to launch a separate retrieval mission).

Once again, a Mars sample return mission is something that will happen in the next decade, not the current one. This means that the likelihood that this mission concept actually happens becomes low, especially if funding stays low. A program that does not actually do anything for eight years represents a sitting-duck in terms of appropriations funding, and unless NASA is very committed to seeing this through, my personal feelings are that we will not see any of these missions happen. Especially when Presidential administrations change, which we are guaranteed to see at least once between now and 2020, possibly twice.

Of course, this is all very fluid. We've seen in the proposed budgets from the House and Senate some money coming back to NASA's Planetary Sciences division. Our advocacy efforts have been well-received and our messages are being heard in D.C. If funding is restored and a real commitment to Mars exploration is present in the Administration, a rover in 2018 (and who knows, maybe earlier?) becomes likely. John Grunsfeld, the head of NASA's Science Directorate, said in a press conference yesterday that a sample-caching mission would have to start work early next year to be ready for 2018. This happens to coincide with the new FY2014 budget being prepared right now. If the Administration and the OMB have truly seen the public's support from the success of Curiosity and our sustained advocacy, there's a chance we'll see this in the new budget. Unfortunately, it's something the public doesn't see until February.

What this means is that we have to keep pressure on NASA, the Administration, and Congress to ensure the survival of the Mars program. There is so much potential and NASA can do so much with so little. We can't let up.

You can read the entire summary of the final report here (8MB PDF).

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth