Marc Rayman • Jul 26, 2012

Dawn Journal: The long, slow goodbye

Dear Dawnpartures,

Dawn has completed the final intensive phase of its extraordinary exploration of Vesta, and it has now begun its gradual departure. Propelled by its uniquely efficient ion propulsion system, the probe is spiraling ever higher, reversing the winding path it followed into orbit last year.

In the previous log (which gained prominence last month by making it into the list of the top 78 logs ever written on this ambitious interplanetary adventure), we saw the plan for mapping Vesta from an altitude of 680 kilometers (420 miles). In this second high-altitude mapping orbit (HAMO2), the spacecraft circled the alien world beneath it every 12.3 hours. On the half of each orbit that it was on the day side, it photographed the dramatic scenery. As it passed over the night side, it beamed the precious pictures to the distant planet where its human controllers (and many of our readers) reside. Tirelessly repeating this strategy while Vesta rotated allowed Dawn's camera to observe the entirety of the illuminated land every five days.

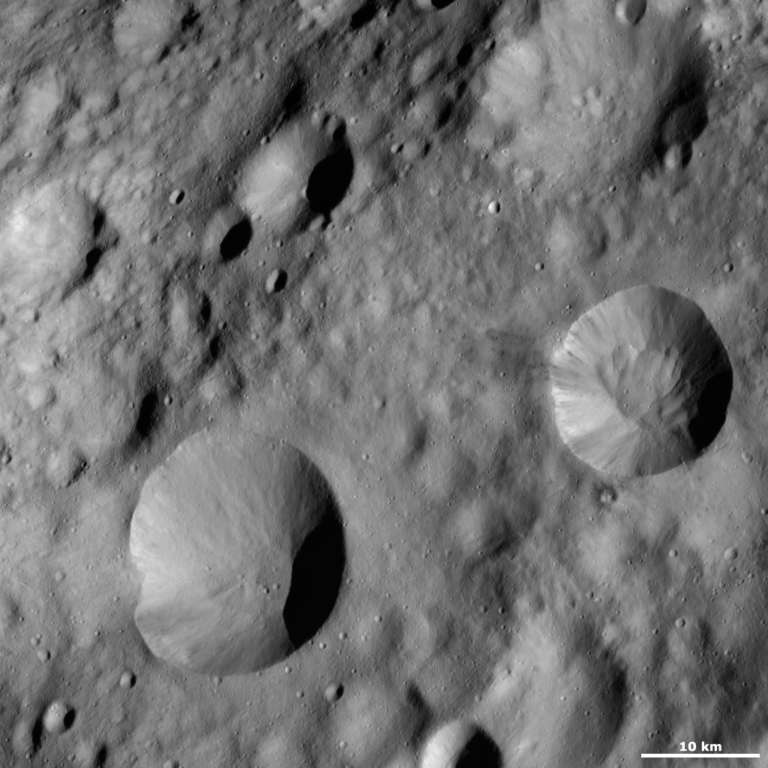

The robot carried out its complex itinerary flawlessly, completely mapping the surface six times. Four of the maps were made not by pointing the camera straight down at the rocky, battered ground but rather at an angle. Combining the different perspectives of each map, scientists have a rich set of stereo images, allowing a full three dimensional view of the terrain that bears the scars of more than 4.5 billion years in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Dawn also mapped Vesta six times during the first high-altitude mapping orbit (HAMO1) in September and October 2011. The reason for mapping it again is that Vesta has seasons, and they progress more slowly than on Earth. Now it is almost northern hemisphere spring, so sunlight is finally reaching the high latitudes, which were under an impenetrable cloak of darkness throughout most of Dawn's residence here.

For most of the two centuries this mysterious orb had been studied from Earth, it was perceived as little more than a small fuzzy blob in the night sky. With the extensive imaging from HAMO1 and HAMO2, as well as from the low-altitude mapping orbit (LAMO), earthlings now know virtually all of the protoplanet's landscape in exquisite detail.

Among the prizes for the outstanding performance in HAMO2 are more than 4,700 pictures. In addition to the comprehensive mapping, Dawn collected nearly nine million spectra with its visible and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIR) to help scientists determine more about the nature of the minerals. This phenomenal yield is well over twice that of HAMO1, illustrating the great benefit of dedicating valuable observation time in HAMO2 to VIR before the mapping.

Dawn's measurements of the peaks and valleys, twists and turns of Vesta's gravity field, from which scientists can map the distribution of material in the interior of the behemoth, were at their best in LAMO. That low altitude also was where the gamma ray and neutron detector (GRaND) obtained its finest data, revealing the atomic constituents of the surface and subsurface. Indeed, the motivation for undertaking the challenging descent to LAMO was for those investigations, although the bonus pictures and spectra greatly enhanced the reward. Even in HAMO2, however, gravity and GRaND studies continued, adding to an already fabulous bounty.

Mission controllers have continued to keep the distant spacecraft very busy, making the most of its limited time at Vesta. Pausing neither to rest nor to marvel or delight in its own spectacular accomplishments, when the robot finished radioing the last of its HAMO2 data to Earth, it promptly devoted its attention to the next task: ion thrusting.

Missions that use conventional propulsion coast almost all of the time, but long-time readers know that Dawn has spent most of its nearly five years in deep space thrusting with its advanced ion propulsion system, the exotic and impressive technology it inherited from NASA's Deep Space 1. Without ion propulsion, the exploration already accomplished would have been unaffordable for NASA's Discovery Program and the unique exploit to orbit both Vesta and dwarf planet Ceres would have been quite impossible. Ion propulsion not only enables the spacecraft to orbit residents of the main asteroid belt, something no other probe has attempted, but it also allows the interplanetary spaceship to maneuver extensively while at each destination, thus tailoring the orbits for the different investigations.

On July 25 at 9:45 a.m. PDT, as it has well over 500 times before, the sophisticated craft began emitting a beam of high-velocity xenon ions. In powered flight once again, it is now raising its orbital altitude. On August 26, the ship will be too far and traveling too fast for Vesta's gravity to maintain its hold. Dawn will slip back into orbit around the sun with its sights set on Ceres.

Although HAMO2 is complete, the spacecraft will suspend thrusting four times to direct its instruments at Vesta during the departure phase, much as it did in the approach phase. The approach pictures aided in navigation and provided tantalizing views of the quarry we had been seeking for so long. This time, however, we will see a familiar world receding rather than an unfamiliar one approaching. But as the sun creeps north, advancing by about three quarters of a degree of latitude per week, the changing illumination around the north pole will continue to expose new features.

On August 15, the craft will interrupt its ascent for four and a half days. By then, Dawn will be at an altitude of about 5,000 kilometers (3,100 miles), but it will still be in orbit. Before it resumes thrusting, it will coast to as high as 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles) and then descend again. Meanwhile, four times during this period it will photograph the giant asteroid throughout a full Vestan day of 5 hours, 20 minutes. This is a familiar activity for the spacecraft, as it watched Vesta rotate beneath it from a similar vantage point during its spiral descent in July 2011. With Vesta's weak gravitational grip at this distance, Dawn would take more than a week to complete one revolution, so it will be almost as if the probe hovers in place as Vesta pirouettes before its camera. The itinerary is planned so the explorer will begin its observations while flying over the highest northern latitudes, and subsequently it will take the opportunity to observe lower latitudes as it sails down to the equator. The ship will circle so slowly that there will be time between acquiring each set of rotation images to point its main antenna to Earth to transmit its findings. After the third session, while waiting for the orbit to carry it to the latitude needed for the final one, mission planners are squeezing in a routine calibration of the camera and VIR. Dawn will turn to aim them at Jupiter. It is much too far away to reveal any new or interesting details, because the sensors are designed for mapping from close orbit. The planet will appear to be little more than a speck. (Terrestrial observers can gain a better view with binoculars.) But Jupiter is bright and easily seen from there, and it is so well studied that it is a useful reference source to verify that the instruments are still performing in top condition as they continue their discoveries at Vesta.

On August 22, nearly 6,000 kilometers (3,700 miles) over the night side, the probe will halt thrusting again. With the sun on the other side of the protoplanet, Dawn will see only a thin glowing crescent against the deep blackness of space, like a new moon. This is a perspective we have not yet had for Vesta, and although not much of the terrain will be visible, a few pictures to measure the strength of the sunlight's reflection at this extreme angle will be useful for understanding certain properties of the surface material. As a bonus, the view may prove to be quite aesthetically appealing.

Dawn will be patiently and gently thrusting at the moment of escape from Vesta on August 26 and will not even notice a change. It will be as serene and uneventful for the spacecraft (and operations team) as the moment of capture was. Shortly after, when it is around 17,000 kilometers (over 10,000 miles) away, it will watch Vesta rotate once again. On September 1, at a distance of 38,000 kilometers (almost 24,000 miles), it will gaze upon Vesta for the last time. By then, the world it has scrutinized for more than a year will be shrinking rapidly and few details will be visible. Although scientists will spend many years delving into the data the probe has returned, learning more and more not only about Vesta but also what it reveals about the dawn of the solar system, Dawn will leave it behind as it journeys deeper into the main asteroid belt in search of another uncharted world to explore.

Dawn is 740 kilometers (460 miles) from Vesta. It is also 2.94 AU (439 million kilometers or 273 million miles) from Earth, or 1,185 times as far as the moon and 2.89 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 49 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

10:00 p.m. PDT July 25, 2012

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth