Ryan Anderson • Mar 22, 2009

Planetary Surface Processes Field Trip: Day 7

The Painted Desert and Petrified Forest

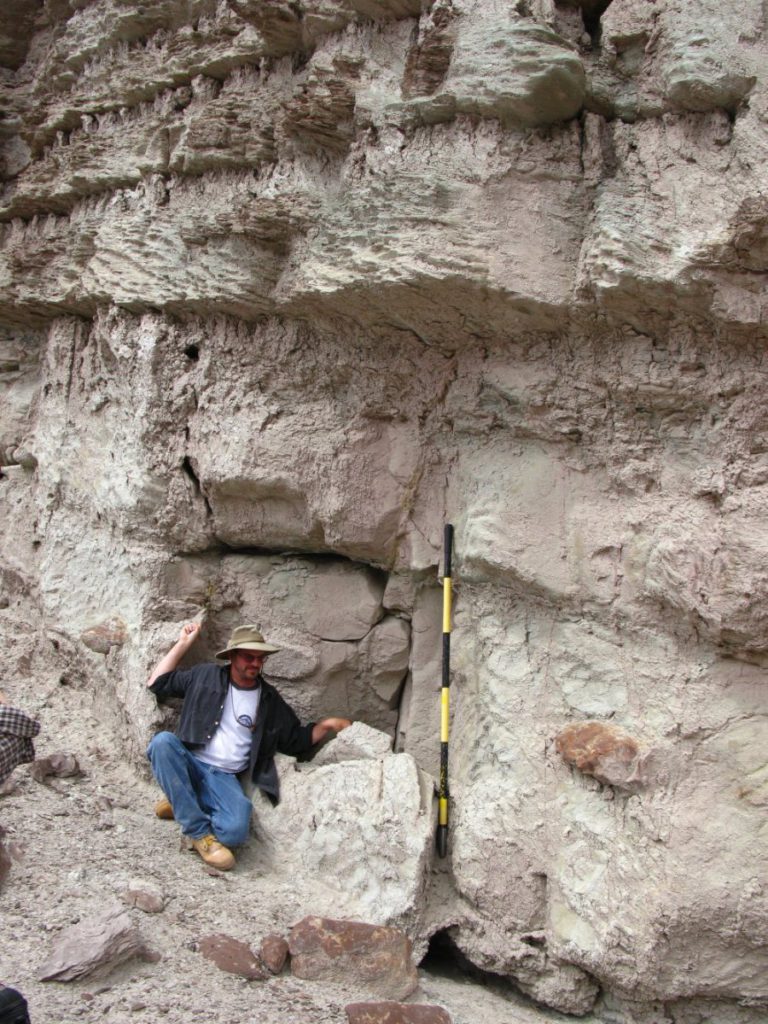

Friday was the last day of the field trip, and we spent it at the Petrified Forest National Park. We were there to study the colorful clays and river deposits, but we began the day with an unexpected bonus: our guide, Bill Parker, is a paleontologist at the park, and he took us to see some of the skeletons that have been found there, and the people who work on them. I spent much of my childhood wanting to be a paleontologist, so to actually see it in action was a special treat. We learned that there is recent evidence that almost all dinosaurs had feathers! We also got to see the reconstruction of what one of the animals may have looked like based on the skull, which was something that I didn’t realize that paleontologists did.

That concludes our geologic tour of Arizona! I went the first version of this trip two years ago, and then as now I was humbled by how complex and difficult to interpret our planet is, even when we can reach out and touch the rocks and analyze them at our leisure. On the other hand, there were many things that we saw from the ground that were much easier to interpret from aerial and satellite data. When you’re on the ground, it is much harder to get an feeling for the overall shape of what you are looking at. A combination of both orbital and ground-based studies is very important to really begin to understand the geology in detail, and even then there is a lot that we can’t figure out!

This trip has also impressed upon me how much more geology I need to learn. I need to know sedimentology and stratigraphy if I’m going to be attempting to read the story hidden in the layered pages of rock on Mars. But for now, I at least know what it is that I don’t know, and that’s a good start.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth