Timothy Reed • Jun 20, 2009

Will Future Spacecraft Come With Warranties?

by Timothy Reed

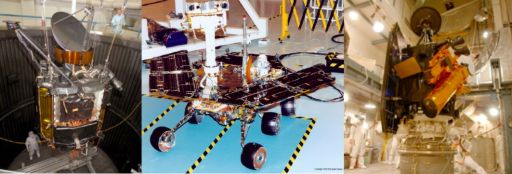

June 19 marked the tenth anniversary of the launch of the QuikSCAT (Quick Scatterometer) satellite that provides NOAA with critical wind speed and direction information over the oceans. The design life of the satellite was two years, but a decade later it is still supplying researchers with data used to predict severe weather patterns and to observe global climate change. The Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, intended to operate on the surface of Mars for 90 days, are still operating--twenty times past their design lifetimes. Granted, Spirit is hobbled by a non-functioning wheel that it drags behind it, but the mission planners are so encouraged by Opportunity's longevity that they sent it on a 12km journey to Endeavour Crater--a trip that will take another year and a half. The Deep Impact flyby satellite, after observing its companion impactor strike Comet 9P/Tempel, still functions and was so economical in its consumption of fuel on its primary mission that it was able to be retargeted to observe another available comet five years later.

Why do these spacecraft exceed their lifetimes by so much? From the perspectives of economics and engineering complexity, it would be preferable to put just enough money, time, and effort into a spacecraft for it to do its intended job. To do any more, it can be argued, is a waste of resources--if a long mission is desired, plan on that from the start.

One factor is that lifetimes are determined by the mission parameters that must be met for the mission to be considered a success. When you're designing, assembling, and testing a spacecraft, there often isn't an easy way to gauge the exact amount of workmanship you need to put in to absolutely achieve the mission goals, but not exceed it by a large margin (although some recent research is attempting to determine optimal design lifetimes to maximize the value in the manufacturing process).

But as an engineer being far more excited about new scientific advancement than the drudgeries of budget analysis, I'm so thrilled when a serendipitous discovery is made when a spacecraft's primary mission is over. Science is all about learning something new that we never even knew existed, and then pursuing new questions based on new information. And the sense of accomplishment that spacecraft developers feel when their hard work continues to function and produce significant discoveries long after anyone thought possible is a powerful motivator--it's a testament to the late hours, scrupulous attention to detail, and commitment to excellence that engineers in this field are known for, and it drives them to continue in that tradition. Even if spacecraft in the future are optimally designed for a specific lifetime, I'm confident that engineers will always put in the extra effort to eke more lifetime out of them.

Timothy Reed is an optical engineer living in Boulder, Colorado. He worked for 20 years developing spaceflight imaging systems and was a major contributor to HiRISE, JWST, NICMOS, QuickBird, Space Shuttle microgravity payloads, and the Pancam mast on the Spirit and Opportunity rovers. He is currently working in the field of holographic optical data storage, and pursuing graduate studies in atmospheric science at the University of Colorado. Timothy has acted in classical theatre for several decades, won medals in luge competitions, and been the voice of a cartoon character.

Timothy Reed is an optical engineer living in Boulder, Colorado. He worked for 20 years developing spaceflight imaging systems and was a major contributor to HiRISE, JWST, NICMOS, QuickBird, Space Shuttle microgravity payloads, and the Pancam mast on the Spirit and Opportunity rovers. He is currently working in the field of holographic optical data storage, and pursuing graduate studies in atmospheric science at the University of Colorado. Timothy has acted in classical theatre for several decades, won medals in luge competitions, and been the voice of a cartoon character.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth