The Adventure of the Planets

This essay was first published in December of 1980 in the first issue of The Planetary Report magazine. Carl's words are as relevant today as they were when he first wrote them. Planetary exploration still needs to be defended from budget cuts, despite the incredible success of past missions and overall public support. The Planetary Society – brand new at the time of writing – thrives to this day. Consider supporting this movement.

For all of human history the planets were wandering lights in the night sky, moving against the background of the more distant constellations in complex, although regular, paths. The planets stirred our ancestors, provoked their curiosity, encouraged mathematics and accurate record keeping. Through the work of Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton, understanding planetary motion led to the development of modern physics and, in a very real sense, opened the modern age of science and technology.

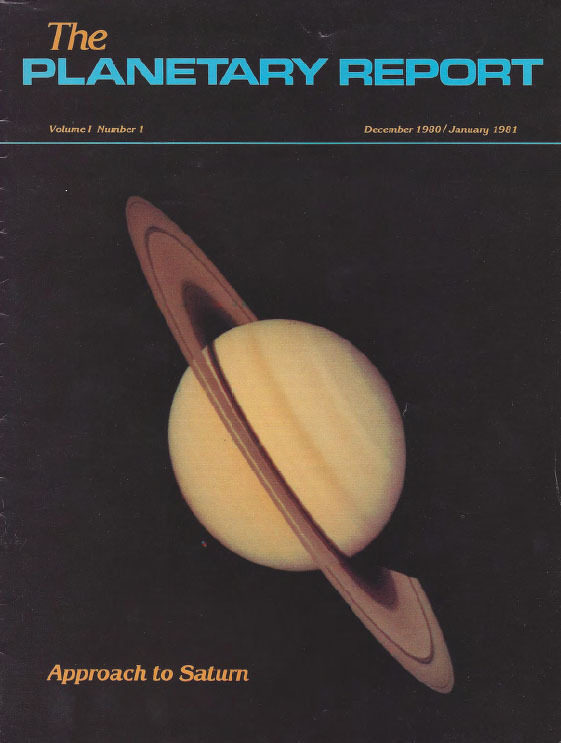

In the last 18 years – ever since the encounter of the Mariner 2 spacecraft with Venus – every one of those wandering lights has been visited by space vehicles from Earth; every one has revealed itself to be a world in its own right very different from our own. We humans have landed exquisite robot spacecraft on Mars and Venus and orbited both planets. We have flown by Mercury, Jupiter, and Saturn. We have discovered the broiling surface of Venus, the windswept valleys of Mars, the sulfur rivers of Io, the great polychrome storm systems of Jupiter. We have discovered new moons, new ring systems, puzzling markings, enigmatic pyramids and have searched for life. Never again will the planets be mere wandering points of light. Because of the effort of the last two decades they will forever after be worlds crying out for exploration and discovery.

"Never again will the planets be mere wandering points of light... they will forever after be worlds crying out for exploration and discovery."

And yet the pace of planetary exploration has slackened ominously. After the Voyager encounters with the Saturn system in November, 1980 and August, 1981, there will be a period of more than four years in which no new images are returned from the planets by any United States spacecraft. The Soviet Union also shows signs of slowing its once vigorous program of space vehicle exploration of the Moon, Venus and Mars – although it is still spending probably two or three times more per year on such enterprises as the United States. If we back off from the enterprise of the planets, we will be losing on many different levels simultaneously.

By examining other worlds – their weather, their climate, their geology, their organic chemistry, the possibility of life – we calibrate our own world. We learn better how to understand and control the Earth. Planetary exploration is an activity involving high technology which has many important applications to the national and global economy – robotics and computer systems being two of many examples. It uses aerospace technology in an enterprise which harms no one, which is a credit to our nation, our species and our epoch. And planetary exploration is an adventure of historic proportions. A thousand years from now, when the causes of contemporary political disputes will be as obscure as the origin of the War of the Austrian Succession is to us now, our age will be remembered because this was the moment when we first set sail for the planets and the stars.

I can remember a Congressman telling me that the only letters he had received in support of the Galileo exploration of Jupiter were sent by people too young to vote.

These arguments are widely accepted. And yet when a specific planetary mission is being considered by the Executive Office of the President or by the appropriate Congressional Committees, planetary scientists hear another story. We are told that it is expensive – although a vigorous program of unmanned planetary exploration would cost about a tenth of a percent of the federal budget; the Voyager spacecraft, when they are finished with their explorations, will have cost about a penny a world for every inhabitant of the planet Earth. But mainly we are told that, although the arguments for planetary exploration are widely understood in government, they are not supported by the people. We are told that spending money on planetary exploration – on the discovery of where we are, who we are, what our history and fate may be – is unpopular, that it is a political liability to support such ventures. I can remember a Congressman telling me that the only letters he had received in support of the Galileo exploration of Jupiter were sent by people too young to vote.

And yet there is evidence of enormous support and enthusiasm for the exploration of the planets. We can see it in the popularity of motion pictures and television programs on planetary themes; in the topics discussed in the burgeoning set of science fact magazines, and in the success with which on this subject have recently been greeted. In puzzling over this apparent paradox, it became clear to me and a number of my colleagues that the solution would be a non-profit, tax-exempt, public membership organization devoted to the exploration of the planets and related themes – particularly the search for planets around other stars and the quest for extraterrestrial intelligence. If such an organization had a substantial membership, its mere existence would counter the argument that planetary exploration is unpopular.

And so Dr. Bruce Murray, the director of Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and I, with a number of colleagues and friends, have established The Planetary Society. The membership of its Advisory Board is not only very distinguished but very broadly based. We believe that many sectors of our society would be willing to support us. We hope to be able to put planetary scientists in touch with their local supporters. With the contributions we have received – some of them anonymous – we have been able to mount a very encouraging sample direct mailing to test the interest of the American public. If we are as successful as at least some experts think we are likely to be, we may be able to accomplish not only our initial goal of demonstrating a base of popular support for planetary exploration; but also to provide some carefully targeted funds for the stimulation of critical activities – for example, in planetary mapping and in the radio search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

DonateThe Planetary Report • December/January

Help advance space science and exploration! Become a member of The Planetary Society and you'll receive the full PDF and print versions of The Planetary Report.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth