David Seal • Jun 02, 2009

Connections

So begins Dante Alighieri's preeminant and oft-quoted allegorical Commedia (later christined La Divina Commedia, or Divine Comedy), widely considered the central epic poem of Italian literature. It was with no small amount of surprise that I found myself, nearly one year ago today, reciting the bulk of the first Canto in its native Italian, walking the cobblestoned streets of Trastevere, wondering - a la David Byrne - how did I get here?

For the last seven years I've been blessed to be the mission planner for Cassini. (Let's not forget, while we're at it, that Cassini was named for Giovanni Domenico Cassini, an Italian.) Each year we have three meetings of the science community to discuss results and do strategic planning for the future. Due to our extensive European participation, we have one of those three in Europe to help balance out the travel burden. Last year it was in Rome.

Trastevere (tras-TEH-veh-ray) is a suburb of Rome, just across the Tiber (the name literally means "beyond the Tiber"). It has retained much of its medieval character and charm, and so was an attractive option to spend an evening decompressing from the day's intensive science meetings. Which is how I found myself there, with a few colleagues, befriended by a native Trasteverino who picked our brains about Cassini, taught us some of the history of Trastevere, showed us where he was born, helped me recite Dante in Italian, and baptized us in the fountain of the Basilica de Santa Maria in Trastevere - one of the oldest churches in Rome. (Now Io sono un Trasteverino.) At the end of the night he gave me a rosary.

I kept the rosary, but had forgotten about it until recently (I'm not Catholic), where it found an interesting and - I hope - worthy use. Over the last two weekends, I was fortunate to play a small role in Bertolt Brecht's Life of Galileo, performed at Caltech. (Caltech astronomer Mike Brown and Spitzer project scientist Mike Werner were among those making key cameos.) Galileo probably seemed a bit dry at times for people not interested in the history of astronomy, but is riveting in at least one respect: it confronts the personal struggles of scientific (and engineering, ahem) integrity and backbone head-on. Galileo may have had the most life experience in this area of anybody. Somewhat later than the "middle of the journey" of his life, he undoubtedly would have sympathized with Dante, facing a dark wood, the straight way lost. He was tried by the inquisition in 1633, found "vehemently suspect of heresy", shown the instruments of torture, forced to recant, and placed under house arrest for the remainder of his life - in other words, made to live with the consequences of his actions. As Brecht speculates on Galileo's state of mind: "I betrayed my profession. A man who does what I did cannot be tolerated in the ranks of science."

I had the honor / dishonor of playing Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, later Pope Urban VII - happily sporting an authentic Roman rosary. He was highly educated and a great lover of art and literature (no doubt he read his Dante), and a friend and admirer of Galileo, opposing his condemnation in 1616 when the first attacks on Galileo reached their climax (before Barberini became Pope). However, Galileo stepped over the line in 1632 with his "Dialogue Concerning the Two World Systems" and alienated Barberini by treating his Aristotelian geocentric view less than kindly, and this led almost directly to his trial and arrest. One of Barberini's colleagues in the play is Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino, who was the principal inquisitor that condemned Giordano Bruno to be burned at the stake in 1600. Bruno was a philosopher, astronomer and heliocentrist, like Galileo, and there is little doubt - in Brecht's play, or in life - that his fate weighed heavily on Galileo's mind during his later years and experience.

Which brings us back to Rome. Curiously, I began my trip to Rome with a pilgrimage of sorts to the Campo dei Fiori ("field of flowers"), where Bruno was executed in 1600. A brooding statue of him adorns the square prominently, commissioned and erected in the 1880s. Nowadays it is a popular spot and a constant cycle of activity, with morning soccer giving way to afternoon cafes, and - appropriately - a flower market on Sunday. A pleasant spot now to have at least a peripheral association with astronomy.

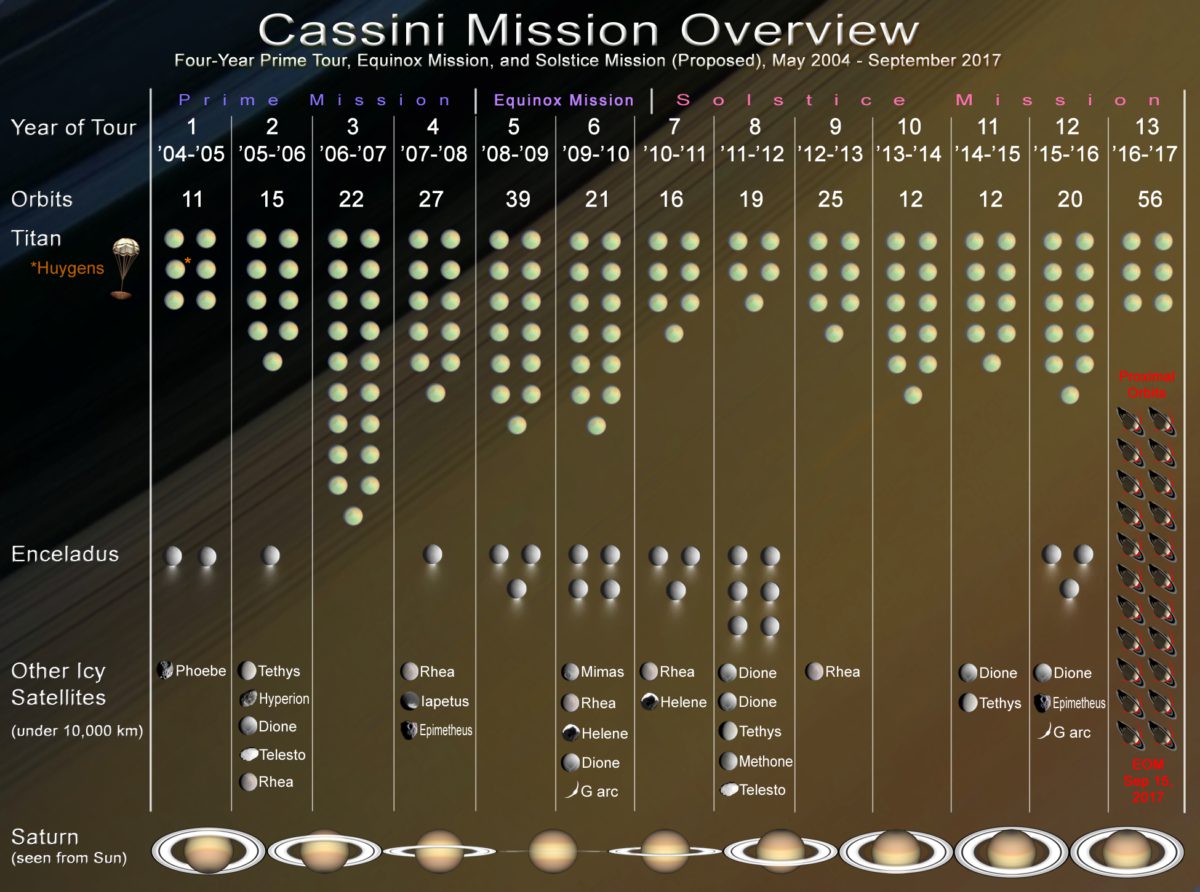

Which brings us back to Cassini. All of these connections have been resonating with the immediate future Cassini now faces. Recently we made a pitch to NASA headquarters for a mission extension to 2017 which Emily and John Spencer were kind enough to blog about here and here. Though we have not heard officially from HQ, it seems likely that they will approve some kind of extension - but whether it will go all the way to 2017 remains to be seen.

The funding level for such a mission is the key question. As is typical for extended missions, we are going to have to make do with less - eventually - to make room for other outer planet missions like the Europa Jupiter System Mission. But how much less? We've proposed 60-70% of our nominal funding. How do we design a tour, and redesign the project teams, to survive, thrive even, with such a significant reduction? How do we ensure that taxpayer dollars are justifiably allocated? These are questions the project has been dwelling on for some time, and is challenging my personal sense of engineering integrity. How do you crew a sailing vessel short-handed? Keep just the officers, cook, and doctor? (Clearly not; what would you do?)

Cassini has had many blessings in its lifetime already. I can say with guarded sureness that no other robotic mission in recent memory has lived in a more target-rich environment, nor delivered a sustained pace of discovery at the same level of scientific intensity. Nowhere else in the Solar System (outside of Earth) can you find so many intriguing phenomena with dynamics on the time scale of a human lifetime. We have also been blessed to have talented spacecraft, sequencing and navigation teams (enabling the discovery) and tour designers who have packed so much into so little time with limited resources. But this can be a curse as well. How do you scale back exploring the most target-rich environment in the Solar System? It feels like braving Dante's dark and dense woods without the benefit of Virgil's guidance. It's not exactly "lovely, dark and deep."

The answers we have come up with so far are still in their infancy, but I hope will serve us well. First, past experience has shown that you can always do more than you think you can. However, this requires somewhat of a leap of faith. Some within the project look upon our proposed tour with trepidation and hand-wringing: "it may be too much!"; "how will we fly this at 60%?"; "we need to place hard limits on what activities are allowed". These concerns are real, and serious. But at times it strikes me like a pearly haze of superstition. Against which I arm myself as best I can against built-in limitations which may severely compromise our activities.

Second, there are smart ways to restructure the project - what my colleagues on other missions call "flattening". In other words, you keep the critical functions, and the engineers and scientists that perform them, and trim back on everything else. Collapse the management structure so you have as few rungs on the ladder as possible between a sequencer and the project manager (yes, we will still need one of those). Third, you plan and allocate for the highest priority science and engineering activities first, and ensure that they get into the sequence before anything else. If the promise of the first answer above bears fruit, then you can get in most of the "nice-to-haves" anyway. And last, you do not build in severe limitations into the design unless you have to. That way you're not caught twiddling your thumbs when your new project and system is more capable than you feared.

Perhaps I'm exaggerating, but at times it feels like we're engaged in a struggle for the very soul of Cassini. How the project confronts its mission extension may not amount to more than a small hill of beans, but it's our duty to grapple with it with all our skills. Will our peers judge us as enlightened explorers, laboring to keep minds open and guide us through dark forests, or high inquisitors, casting away possibilities and hope, claiming to be guarding a precious soul from wandering astray, but doing evil in the name of the common good? I hope for the former, but only time will tell.

I can only close by matching quotes from Bertolt Brecht with co-founder Carl Sagan. And one from Galileo - not to take everything so seriously.

"Truth is born of the times, not of authority. I have had the unimaginable luck to get my hands on a new instrument that lets us observe one tiny corner of the universe a little. Make use of it." [Brecht]

"The truth may be puzzling. It may take some work to grapple with. It may be counterintuitive. It may contradict deeply held prejudices. It may not be consonant with what we desperately want to be true. But our preferences do not determine what's true." [Sagan]

"The Sun, with all the planets revolving around it, and depending on it, can still ripen a bunch of grapes as though it had nothing else in the Universe to do." [Galileo]

(P.S. On tap for the rest of the week, you can look forward to less philosophy/travelogue and more real science and engineering!)

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth