Alan Stern • May 20, 2009

LRO, LCROSS, and the Search for Lunar Ice Begins Anew Next Month

by Alan Stern

Ever since the early 1960s, there has been continuing and serious scientific discussion of the possibility that water, in the form of ice imported to the Moon by comets and other impactors, which may have accumulated at the lunar poles.

Why the lunar poles? Because there are deep craters there whose floors never see sunlight (even indirectly off crater walls), and which therefore may have remained cold trap sanctuaries to any ice that may have been directly (e.g., by impact or by surface reactions between solar wind hydrogen and lunar soil, which is rich in oxygen) or indirectly deposited there (e.g., by thermal migration to the poles after deposition elsewhere by impacting, ice rich bodies). Altogether, calculations indicate the lunar poles could contain billions of tons of water ice deposited by one or more of these processes.

Of course, the LP hydrogen signature could also be fooling us. For example, some researchers suggested ways it could be created by solar wind hydrogen implantation or even by methane or other organic molecule deposits. But if there is ice at the poles of the Moon, it would be a very important resource, both for lunar explorers and for science. The benefit to exploration would be the prize inherent in using the ice to produce drinking water, coolants, oxygen for breathing, and hydrogen for rocket propellant. The prize for science would be the treasure trove of information that the ice might contain. Some scientists want to profile the ice abundance with depth to determine the record of lunar (and Earthly) cometary bombardment over time; others have even suggested that the return of such ice to Earthly labs would constitute a quick and less expensive way to get a "poor man's" comet sample.

With such important attractions, plus the sheer public excitement that a confirmed store of lunar ice could create, NASA focused a good deal of the scientific firepower aboard its Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) mission on the objective of searching for lunar polar ice. LRO is set to launch next month. (See http://lunar.gsfc.nasa.gov/ for more information on LRO; and also see Jim Bell's nice article from two weeks ago here in the blog.)

What is clear about lunar polar ice is that it is hard to confirm with any single technique from orbit. And although it would be much easier to confirm with a properly equipped polar rover, such a mission would be far more expensive than LRO and is not yet on the books. NASA planners putting together the payload for LRO recognized both of these facts, and assembled an armada of five separate instruments that could search for the ice from orbit, each using an independent and complimentary technique. These are

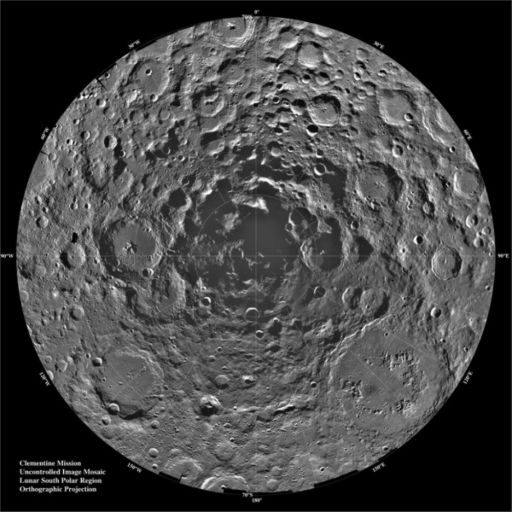

- Diviner: Which will carefully map the polar cold traps to directly determine where ice can remain thermally stable for billions of years.

- LAMP: Which will use the faint glow of ultraviolet starlight and hydrogen's Lyman alpha emission line in interplanetary space to illuminate the polar regions and allow a spectroscopic search for exposed water frost. (By the way, I was the originator of and PI for LAMP before I went to NASA Headquarters.)

- LEND: A more sophisticated neutron spectrometer than LP carried, allowing better localization of the excess hydrogen deposits.

- LOLA: A laser altimeter which be able to shine its laser in the polar regions to look for high reflectivity spots that might correlate with LAMP or LEND evidence for water. And,

- Mini-Rf: A radar capable of a more definitive search for ice -- even buried ice -- than Clementine was capable of.

Far more likely, we will either have found such strong evidence for it, that its existence would be very hard to refute, or we will have learned that the current but only tantalizing evidence for it was caused by something other than water molecules. Either way, the answer to this important puzzle piece will be in hand in a matter of months if all goes as planned.

Go LRO, Go LCROSS, Go Lunar Exploration!

Alan Stern is an Associate Vice President at the Southwest Research Institute and a consultant to various universities and aerospace firms. In 2007 and 2008 he directed all of NASA's space and Earth science programs as a NASA Associate Administrator. He is a planetary scientist, NASA mission and science instrument PI, and has authored and edited a variety of books on space science and space exploration. His research interests include the origin and architecture of planetary systems, planetary atmospheres, and comets. By not sleeping very much, he also finds time to enjoy raising his three children, and to hike, vacation, and write.

Alan Stern is an Associate Vice President at the Southwest Research Institute and a consultant to various universities and aerospace firms. In 2007 and 2008 he directed all of NASA's space and Earth science programs as a NASA Associate Administrator. He is a planetary scientist, NASA mission and science instrument PI, and has authored and edited a variety of books on space science and space exploration. His research interests include the origin and architecture of planetary systems, planetary atmospheres, and comets. By not sleeping very much, he also finds time to enjoy raising his three children, and to hike, vacation, and write.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth