Emily Lakdawalla • Mar 26, 2009

Look! It's a near-Earth asteroid!

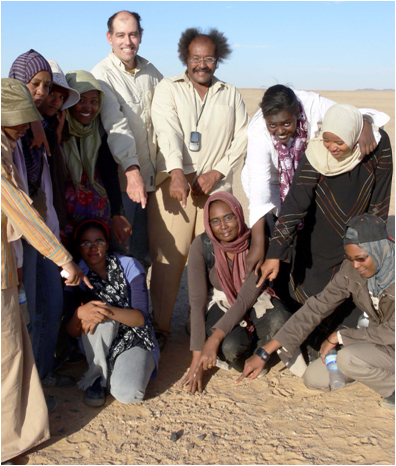

One cool photo deserves another. This one is of some of the members of the field campaign that turned up about five kilograms' worth of meteorites that are all that remain of asteroid 2008 TC3. Amir Alexander has just posted a news story summarizing the recovery of these meteorites.

A startling sight greeted the faithful in the Nubian desert of northern Sudan as they emerged from morning prayers on October 7, 2008. White smoky streaks hovered in the air above them, forming ghostly patterns in the morning skies. Faced with this strange phenomenon, the Sudanese villagers did what any citizens of the 21st century would do in such circumstances -- they took pictures with their cell-phones. And that is how the impact of asteroid 2008 TC3 -- the only asteroid to be tracked in space before striking the Earth -- was recorded for posterity.

It was also fun to hear from meteorite researcher Mike Zolensky. "You can imagine my excitement when I first heard from Peter [Jenniskens] that not only had he recovered samples from the asteroid, he was going to send them to me for analysis." I can't imagine, actually. It's one of the most annoying challenges in meteoritics -- meteorites provide an amazing opportunity for us to analyze actual pieces of asteroids from all over the solar system, but figuring out how classes of meteorites correspond to the different colors and types of asteroids is a knotty problem, and scientists can never be confident they've got it right. This was the absolutely first time that we have observed an asteroid in space, measured its color and its other properties, then had it plunge through the atmosphere, explode, and become a pile of meteorites on the ground. We have the full chain of evidence.

So it's slightly sad that the meteorite turned out to be such an oddball, a ureilite, which is a type of meteorite that makes up only about 1/2 to 1 percent of all falls. (Though, as Lucy McFadden pointed out on the teleconference, they may actually be more common than that in the asteroid belt; ureilites are exceedingly porous and fragile so survive to the ground less easily than your more typical stony or iron meteorites.) But the good news is that the observations of the asteroid and the identification of the meteorites on the ground unequivocally connect ureilites with F-class asteroids.

We actually even got spectra on this thing in the few hours between its discovery and its demise. A group of British astronomers using the William Herschel Telescope on La Palma managed that feat a mere 4.5 hours before impact, when it was really zipping across the sky. They actually confirmed that the spectra of the asteroid while it was in space look pretty similar to spectra gathered of the meteorite in the lab. That's good news.

This story wouldn't have been possible without the persistence of Peter Jenniskens, who took the information on the asteroid's likely impact location provided by Chesley and went to Sudan, and then established a professional connection with Sudanese researcher Mauwia Shaddad, so that the two of them together could venture out into the Nubian desert (with the help of an army of dozens of students) to find those bits and pieces of meteorite. It was a student, Mohammed Alameen, who found the very first meteorite fragment, not two hours after the start of the search. I don't know whether Alameen is in the photo at the top of this entry; I'm guessing not, because it looks like all the students pictured are women. I suppose it doesn't really matter. All those students got to participate in the fun of a real live treasure hunt, and contribute to a major scientific advance. I'd be grinning the same way if I were them!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth