Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 28, 2009

Treasures from Mars' ancient history

One of the things I do when contemplating a move or, really, any other major life change, is to go through my library and sell a bunch of books. It's a symbolic thing, an attempt to clear some of the clutter before I make whatever new start is about to happen, although mysteriously it never seems to result in me owning fewer books than I owned previously. It's gotten easier (and more lucrative) to get rid of books in recent years; rather than abandoning them in some random bookstore for peanuts I just list them on half.com and manage to sell quite a few into good homes, sending them directly to people who want them. But there's always a refractory stack of books left that just won't sell, and those I have to put into a box and take to some random used bookstore.

That's where the danger lies. I recently discovered a wonderful used bookstore near my office, one that strikes just the right balance of order and chaos; the majority of books are on shelves and all are sorted into subjects, but the shelves overflow into stacks and stacks of books piled everywhere on the floor. Yet the owner is never dismayed to see even more books come into the store. When he sees I have academic texts he tells me it'll take a little while to value them, and so, of course, I browse. Bad idea -- this store is only a few blocks from Caltech so has much to interest me. Like most used bookstores, Book Alley offers more value in trade than in sale, so, rather than accept the relatively tiny (compared to half.com) amount of money offered for my books, I come to the counter with a big stack, and wind up poorer after the transaction is over. (Don't tell my husband.)

Poorer, that is, in purely financial terms, and that's a narrow way of looking at the world, right? Right? (Support me here, guys.) The treasures I found yesterday! Evidently there is someone living nearby, who must be in his 70s or 80s (because he must have had enough money to spend on lots of books in the early 60s), who is slowly divesting himself of a rather large space-related library. It seems he recently unloaded a pile of books relating to the early history of Mars exploration, including several NASA special publications on the Mariner missions (4, 6, 7, and 9) and the Viking orbiters and landers. And I picked up a copy of Tim Mutch's influential opus Geology of the Moon: A Stratigraphic View. But the diamond among all of these was a copy of Earl C. Slipher's Mars: The Photographic Story.

Slipher (1883-1964) was an astronomer who studied Mars from the storied Lowell Observatory, the same place from which Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto. From 1907 until his death he studied Mars from Lowell, producing an unrivaled time-series of photographs of the Red Planet at every opposition. The book I purchased was published just two years before his death and contains reproductions of his photos from 1907 to 1961, as well as a lengthy text describing his observations and the conclusions he drew from them. According to sources on the Internet Slipher, like his observatory's founder Perceval Lowell (1855-1915), saw canals on Mars and believed they were evidence for present or past civilizations. My quick scan of the text didn't turn up any mention of canals, but they're there in the maps published at the beginning of the plates in this book. Also Slipher (like many planetary astronomers) had observed the waxing and waning of a blue-green color across Mars' surface over time, which he interpreted to be seasonal variations in vegetative cover.

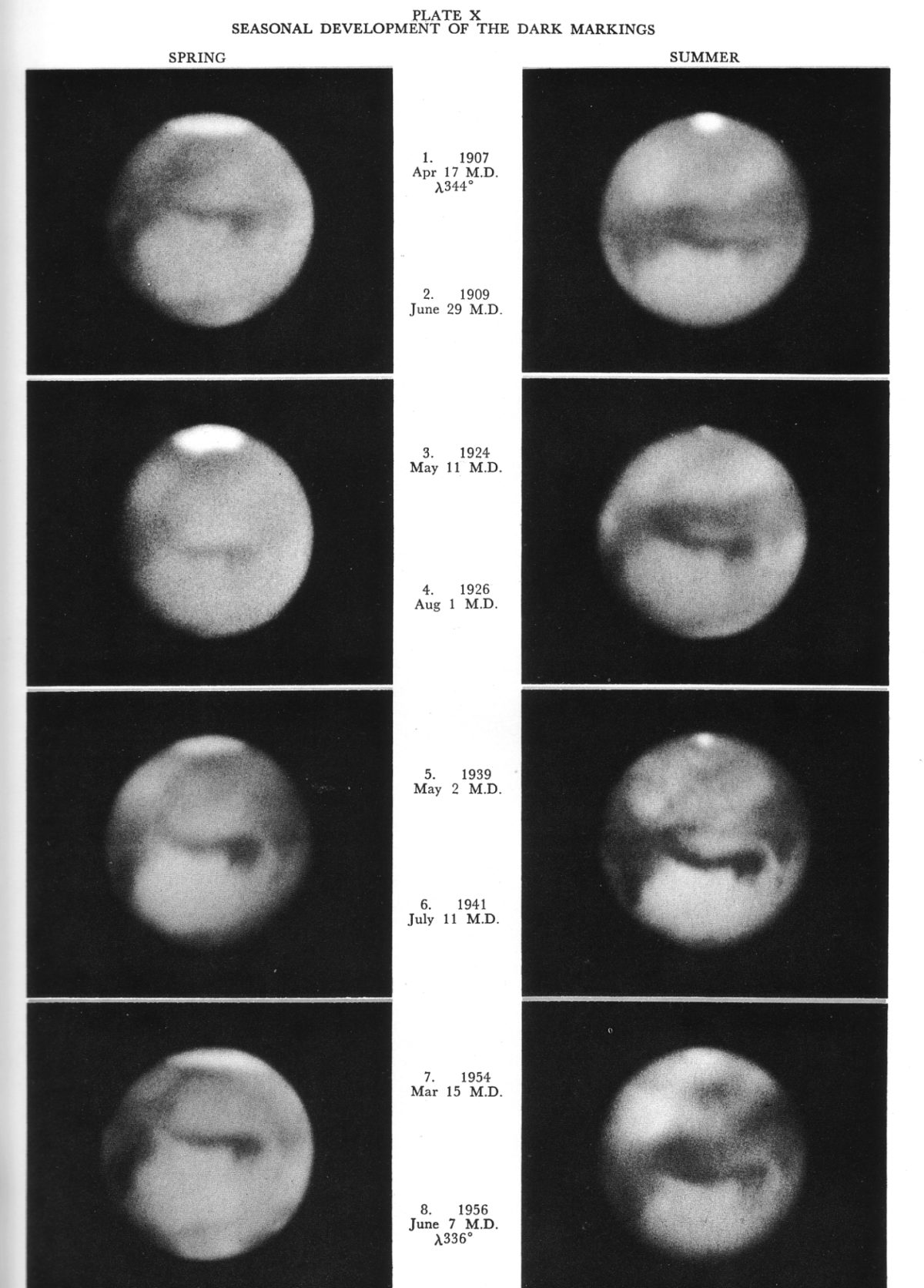

Here's one plate in which Slipher draws upon half a century of his work photographing Mars to illustrate these seasonal variations; laudably his caption only describes what he saw, presenting it with a minimum of inference. (His inferences are in the book's text.)

Although not described in connection with the foregoing series of seasonal changes, the Hellespontus, Mare Ionium, Mary Tyrrhenum also were partly involved.

In a similar manner the series of dark regions in the southern hemisphere of the planet undergo a summer darkening. However, the Pandorae Fretum stands so completely alone on the planet that its appearance and disappearance with the seasons is most obvious and the fact that it completely vanishes into the ochre desert in winter makes it by far the easiest seasonal change to recognize.

Slipher's photographs don't hold a candle to even the most primitive images returned from the early Mariner missions. But we've been observing Mars from spacecraft for less than half a century. Slipher's photographic records extend our knowledge of Mars back to the first decade of the twentieth century. They are a cultural treasure.

I'd like nothing more than to curl up on the couch with a cup of coffee and read Slipher's text, his distillation of a professional lifetime of work, a major part of the foundation on which the scientific goals of our first robotic emissaries to Mars were built. I've never known a time when we hadn't seen the surface of Mars and indeed every other major planet and moon in the solar system out to Saturn and beyond. It's difficult for me to respect the darkness and mystery that confronted the designers of the first interplanetary spacecraft; I know that reading Slipher's book will help me to understand how bounded our knowledge was then, and what a revolution the first Mariner images were.

But it's time to pack, so these and the other books I just bought are, sadly, going straight into a box where they can't distract me until after I move. In a few weeks, as I'm wearily going through the process of opening one box at a time and wondering dully where on Earth I am going to put all these books and their bookcases, I'll stumble across Slipher, go make myself a pot of coffee, and settle onto the couch to read.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth