Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 13, 2008

DPS meeting: Saturday: Studying extrasolar planets with planetary spacecraft

I'll be writing quite a bit about the annual meeting of the Division of Planetary Sciences (DPS) of the American Astronomical Society this week; see this post for an introduction.

One of the first sessions at DPS was on results from the EPOXI mission, which is what they are calling the Deep Impact extended mission. There are two components to the extended mission: Deep Impact is on a long cruise toward a second cometary encounter, with Hartley 2 in 2010; but in the meantime, astronomers are using Deep Impact's defocused high-resolution imager to study known transiting exoplanets, and also to study Earth as though it were an exoplanet. What's a transiting exoplanet? It's a planet that orbits another star, which has been detected from Earth by the way it dims the light from its star as it crosses in front of the star on its orbit. In order for a planet to be detected this way, we have to be looking at the star system edge-on, so it's only possible for us to detect such exoplanets around the small fraction of stars whose planetary disks just happen to be oriented that way.

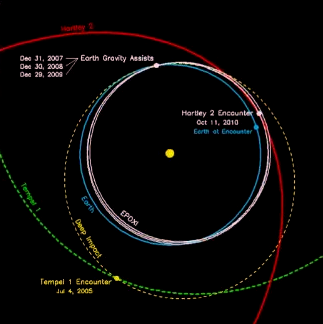

NASA / JPL

Orbital path of Deep Impact during the EPOXI mission

Deep Impact's extended mission is actually two: The EPOCh mission involves Extrasolar Planet Observation and Characterization and is performed while Deep Impact cruises, and the DIXI mission is the Deep Impact Extended Investigation, in which Deep Impact will fly by a second comet, Hartley 2, on October 11, 2010. Three Earth gravity assists are required to set up the Hartley 2 flyby, on December 31, 2007; December 30, 2008; and December 29, 2009.

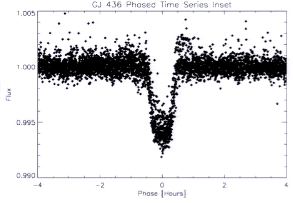

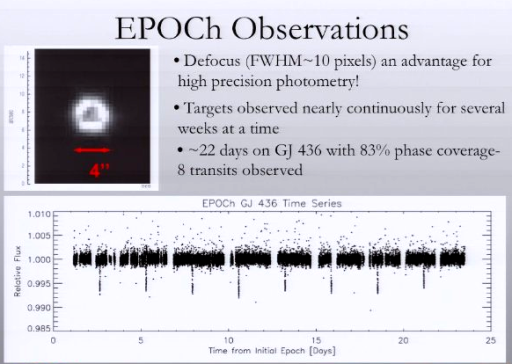

from Sarah Ballard's presentation to the 2008 DPS meeting

A defocused telescope aids study of transiting exoplanets

The upper left image shows what a stellar light source looks like to the defocused high-resolution camera on the Deep Impact spacecraft. This defocus was a problem for high-resolution imaging of the nucleus of comet Tempel 1, but it is actually helpful for Deep Impact's extended mission to study the light curves of transiting exoplanets. The defocus spreads the signal over many pixels, allowing much longer exposure times and increasing the sensitivity to the minute changes in stellar flux when a planet partially occults the star. The plot at the bottom shows 22 days of data from the hot Neptune GJ 436. Gaps in the data occur when Deep Impact had to turn to Earth to return data.

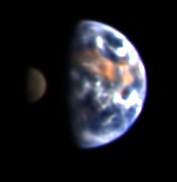

NASA/JPL-Caltech/UMD/GSFC

The Earth and Moon, from Deep Impact

This image of the Earth and Moon was taken by Deep Impact on May 29, 2008 from a distance of 49,367,340 kilometers (30,675,43 miles). The image was taken with three filters -- blue, green, and orange -- as part of a campaign to study Earth as though it were an extrasolar planet.

NASA / JHUAPL

Earth in true and false color as seen by MESSENGER

This pair of images represents the same viewpoint on Earth through two different sets of filters on the MESSENGER spacecraft. On the left, three filters in red, green, and blue wavelengths were combined to make an image that approximates what the human eye would see. The green mass at the center is the Amazon jungle of South America. The deserts of West Africa are just visible on the edge of the Earth's disk below and to the right of South America. The right-hand image is "pushed" into the near infrared; instead of red, green, and blue, it is composed of images taken through near-infrared, red, and green filters. Chlorophyll, the green pigment in plant leaves, is very strongly reflective at near infrared wavelengths, much more so than it is in red or green wavelengths, so the vegetated parts of Earth burst into bright red color.David Grinspoon presented the results of a similar experiment being performed by Venus Express. At Venus Express' distance from Earth, its highest-resolution VIRTIS instrument can't even resolve Earth -- it's always much smaller than one pixel -- which is actually a better analogue to future studies of extrasolar planets. If VIRTIS can't see Earth as a disk, it does get excellent data on Earth's spectrum, which is fun to study from a distance because of all of the different sources of variability: the spectrum changes as Earth rotates, bringing more continents or more oceans into view; it changes as weather patterns increase or decrease cloud cover and change their distribution; it changes with the seasons, as more or less ice covers the northern hemisphere (the southern hemisphere, having much less continent, shows much less seasonal ice cover variability); and so on. Again, the presentation didn't contain any real surprises; more than anything else it demonstrated that VIRTIS has captured a valuable, real-world data set that will be useful in developing models of what might be causing spectral variability on distant worlds that we will someday study with powerful telescopes.

ESA / VIRTIS / INAF-IASF / Obs. de Paris-LESIA

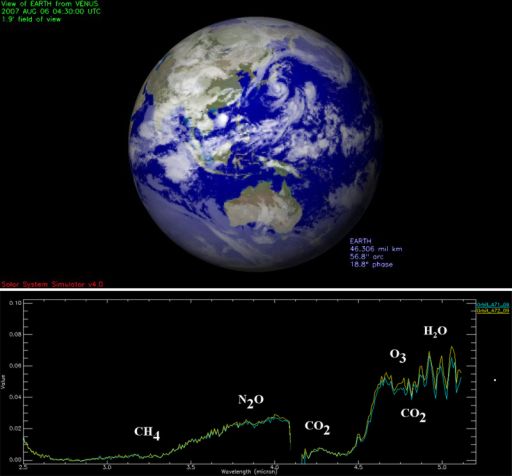

VIRTIS observes Earth as an extrasolar planet

Periodically, Venus Express has turned its VIRTIS instrument to distant Earth. At Venus Express' distance from Earth, the planet is always much smaller than one pixel. However, VIRTIS is able to study the spectrum of the planet -- how it reflects light at different wavelengths -- and the wiggles and dips in the spectrum are diagnostic of the presence of several atmospheric gases. This data set is valuable for scientists who are searching for Earth-like planets around other stars.Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth