Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 20, 2008

Things that probably won't ever be called planets, but maybe they should

EDIT: I have now posted a single-image version of the scale asteroids and comets montage for your downloading pleasure. --ESL

The longer I listened to the "great planet debate" last week, the more strongly I felt that if it were up to me, I would define "planet" to mean "everything in the universe that's smaller than a star." The fact of the matter is, every time I speak about any object visited by a spacecraft, I make frequent slips of the tongue. I call Titan a planet. I call Enceladus a planet. I've even called Tempel 1 a planet. They're all wanderers, all places to visit. Subdivide it however you like -- it makes sense to speak of giant (or Jovian) planets, ice giant planets, major planets, terrestrial planets, minor planets, dwarf planets, binary planets, whatever. But just look around at the people who call themselves "planetary scientists" and see what they study. It's all of the above.

In that spirit, I went around the Internet to locate all of the really tiny Sun-orbiting worlds that have been visited by spacecraft, the ones too lumpy and common to fit into nearly anybody's definition of "planet." Yet, by virtue of having been visited by a spacecraft, they have been elevated to special status. Here's the gallery. Many thanks to Ted Stryk for rummaging through his archives and sending me his versions of many of these images.

The first of these minor planets to have been visited by spacecraft was, fittingly, the first comet that was recognized to be a periodic one: Halley's comet. A flotilla of spacecraft was launched to visit Halley when it last visited the inner solar system in 1986, including ICE (USA, NASA), Vega 1 and 2 (Soviet Academy of Sciences, USSR), Sakigake and Suisei (ISAS, Japan), and Giotto (ESA). Of these, Vega 1, Vega 2, and Giotto returned photos of Halley's nucleus, finding it to be good-sized for a comet at 16 by 8 kilometers across, but incredibly dark and also extremely low-density (if you're curious, the density was 0.1 grams per cubic centimeter). Here's a photo from Vega 2:

Russian Academy of Sciences / Ted Stryk

The nucleus of Halley's comet

The Vega 2 spacecraft returned many images of the nucleus of Halley's comet on March 9, 1986. The nucleus is an irregular object about 16 x 8 x 8 kilometers and very dark, with an albedo of about 0.03. The next time Halley will approach the inner solar system is in 2062.

NASA / JPL

Ida and Dactyl in enhanced color

Galileo captured this image of asteroid Ida and its moon Dactyl about 14 minutes before its closest approach on August 28, 1993. The range from the spacecraft was about 10,500 kilometers (6,500 miles). This was from the imaging sequence that produced the discovery of Dactyl. The color is based on violet and infrared filters; it represents actual variations on the surface of Ida, but has little relationship to the colors that human eyes would see. Ida is an S-type asteroid, about 58 by 23 kilometers in size.

NASA / JPL / Ted Stryk

Dactyl

Also known as (243) Ida I, Dactyl is a satellite of the asteroid Ida. Dactyl was discovered by the Galileo spacecraft in images taken as it sped past Ida in an encounter on August 28, 1993. It is about 1.6 by 1.2 kilometers in size, orbiting Ida at a distance of 90 kilometers.

NASA / JPL / Ted Stryk

Asteroid Mathilde

Asteroid 253 Mathilde was visited by the NEAR spacecraft on June 27, 1997, on its way to Eros. The encounter was the first fast flyby of an asteroid; for the images to be captured, the spacecraft's targeting had to be updated less than 12 hours before the encounter, based upon the orbital information provided by pre-encounter images. Mathilde is a C-type main-belt asteroid, 59 x 47 kilometers in size.

NASA / JHU APL

Eros rotation animation

One full rotation of the asteroid Eros as seen by the NEAR spacecraft on February 16, 2000, two days after its arrival. Eros is an S-type asteroid, about 33 by 13 kilometers in size.Source

NASA / JPL / Ted Stryk

Asteroid Braille

Deep Space 1 flew by asteroid 9969 Braille (formerly known as 1992 KD) on July 28, 1999, at an altitude of only 26 kilometers. However, the only images of Braille were captured from much farther away, about 14,000 kilometers. Braille proved to be an irregularly shaped body about 2.2 kilometers long by 0.6 kilometers across. It is probably a Q-type asteroid, dominated by olivine and pyroxene. It is also unusually bright for an asteroid, with an albedo of about 0.34.

NASA / JPL / Ted Stryk

Asteroid Annefrank

The Stardust spacecraft flew within 3,300 kilometers of asteroid Annefrank on November 2, 2002. Prior to the encounter, little was known about the asteroid except how much light it reflected. It turned out that the brightness of Annefrank had been interpreted incorrectly, leading mission planners to expect a smaller and brighter asteroid. Its size is 6.6 by 5.0 by 3.4 kilometers.

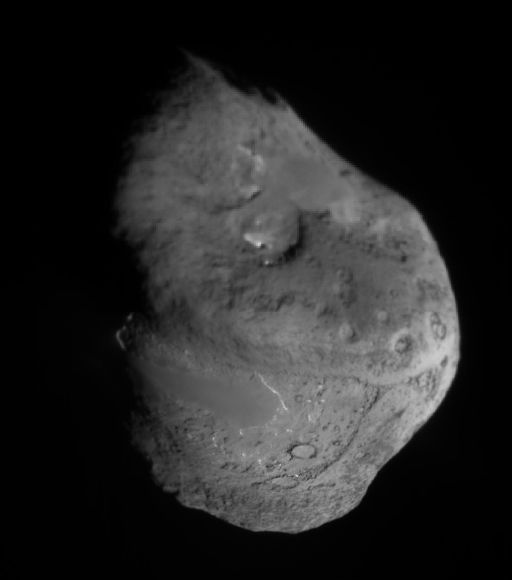

NASA / JPL / UMD

Mosaic of Tempel 1

This view of the nucleus of comet Tempel 1 is composed of many frames captured from different ranges by Deep Impact as it approached for its July 4, 2005 encounter. Images of the whole comet nucleus were taken from a greater distance and so are blurrier; highest resolution images were captured of the bottom half of the nucleus.

ISAS / JAXA / Øyvind Guldbrandsen

Itokawa rotates under Hyabusa

This animation consists of 57 separate images captured by the Hayabusa spacecraft as the tiny asteroid Itokawa (535 by 294 by 209 meters in size) rotated underneath it. The images are actually from three separate rotations; they were sorted and lined up into this animation by Øyvind Guldbrandsen of the Norwegian Astronautical Society. Click here for a full-resolution movie containing 169 frames (AVI format, 3.8 MB)One thing I always wonder when I look at such photos is: how big are they? In particular, how do their sizes relate to each other? Here you go, all of the minor planets pictured above at the same resolution, 200 meters per pixel. Itokawa really is there, it's just a nearly invisible 2-by-1-pixel speck.

|

Asteroids above and left;

| ||||||||

Mathilde | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Ida 58 x 23 km |

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth