Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 30, 2008

First science results from the MESSENGER Mercury flyby

The MESSENGER mission held a press conference this morning to describe the first, preliminary conclusions from the first Mercury flyby. I'd say that the overarching conclusion is: MESSENGER will produce an absolutely fantastic data set. What we've seen so far is just a taste of what's to come. I wrote up a detailed story on the Mercury science results with lots of pictures here. I have to hand it to the MESSENGER team: they didn't pull any punches when it came to the science. I liked that but it did make it a bit challenging to get my story finished today -- it took a lot of effort to work through all those details and try to find ways to explain the science. In the end, I didn't have time to post it until after I put the baby to bed tonight. And almost none of what was presented today made it into the Associated Press story on the flyby (except the "spider" -- read my story to see what that is).

NASA / JPL / CIW / Emily Lakdawalla

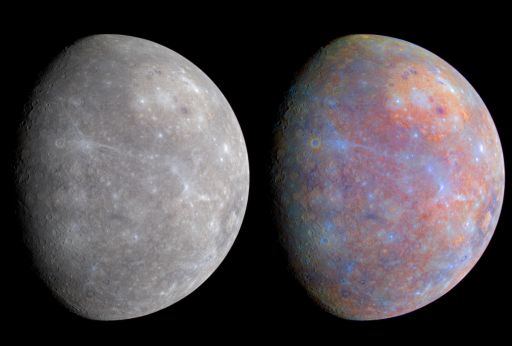

Mercury's colors

The image at left represents a false color view of Mercury captured by MESSENGER as it sped away from its first encounter with the planet on January 14, 2008. The image is composed of three captured through filters with wavelengths of 1000, 700, and 430 nanometers (infrared, red, and violet), covering a wider range of the electromagnetic spectrum than human eyes can see. The image on the right is the same, but the saturation of its colors has been severely enhanced. The garish colors pick out interesting compositional differences across the surface. Fresh craters and their rays show up as bright blue. The Caloris impact basin appears deep orange, surrounded by a dark red ringl craters in its interior have deep purple rims. To the south, near Mercury's limb, a violet stain surrounds the crater Tolstoj, which, like Caloris, has an orange interior. These color differences hint at compositional differences, but exactly how the composition differs is not yet known.However, if you're resourceful, and if you're not constrained by the desire to be scientifically exact about how you process an image, you can achieve a pretty good approximation of a true-color view of Mercury from the data that's already been released. Eric Landreneau sent me these two versions of the released views, with their colors manipulated so that they approximate the colors that you might see if you were there.

Finally, I'll post a couple of notes from today's press conference that didn't make it into my story. One of the press questions at the end was from a tiny local radio station who said that he knew he was being listened to by an audience of schoolkids; what would the science panel say to those kids? One panelist, Bob Strom, talked briefly about how much of a "turn-on" science was, which was a bit awkward; but, with a couple more minutes to think, Sean Solomon really stepped up. Here's what he said, which is, I think, a good message to deliver to high school kids, or college kids, kids old enough to realize they almost certainly will not be astronauts (just like, with only rare exceptions, they almost certainly will not be professional sports players or movie stars or President): there's many different ways to contribute to space exploration, many different challenges you can attempt to meet, depending upon your own strengths and inclination:

Space exploration is a lot more than space science. We're flying a spacecraft that owes its origin and livelihood to hundreds of engineers and technicians who designed it, who worried about how it would survive so close to the Sun, how it would survive radiation, how it would live for nearly 8 years, how it would communicate its scientific findings back to the Earth, how it would get launched, how it would find its way billions of miles, 15 times around the Sun, to get into Mercury orbit 6 and a half years following its launch. There are a lot of ways to contribute to space exploration. Science is one of them. The engineering of building, operating, and maintaining spacecraft is a terrific field, and we [gesturing to the panel] would not be up here if we did not have an outstanding team of engineers who put this spacecraft together and keep it going.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth