Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 31, 2015

Planetary Exploration Timelines: A Look Ahead to 2016

How many planetary exploration missions are there, and where are they? These days, it's hard to keep track, because there are so many. I plan to begin the new year by taking stock of active missions, figuring out what each has set out to do and accomplished so far, but first I want to step back to consider the spread of missions across the solar system as a whole.

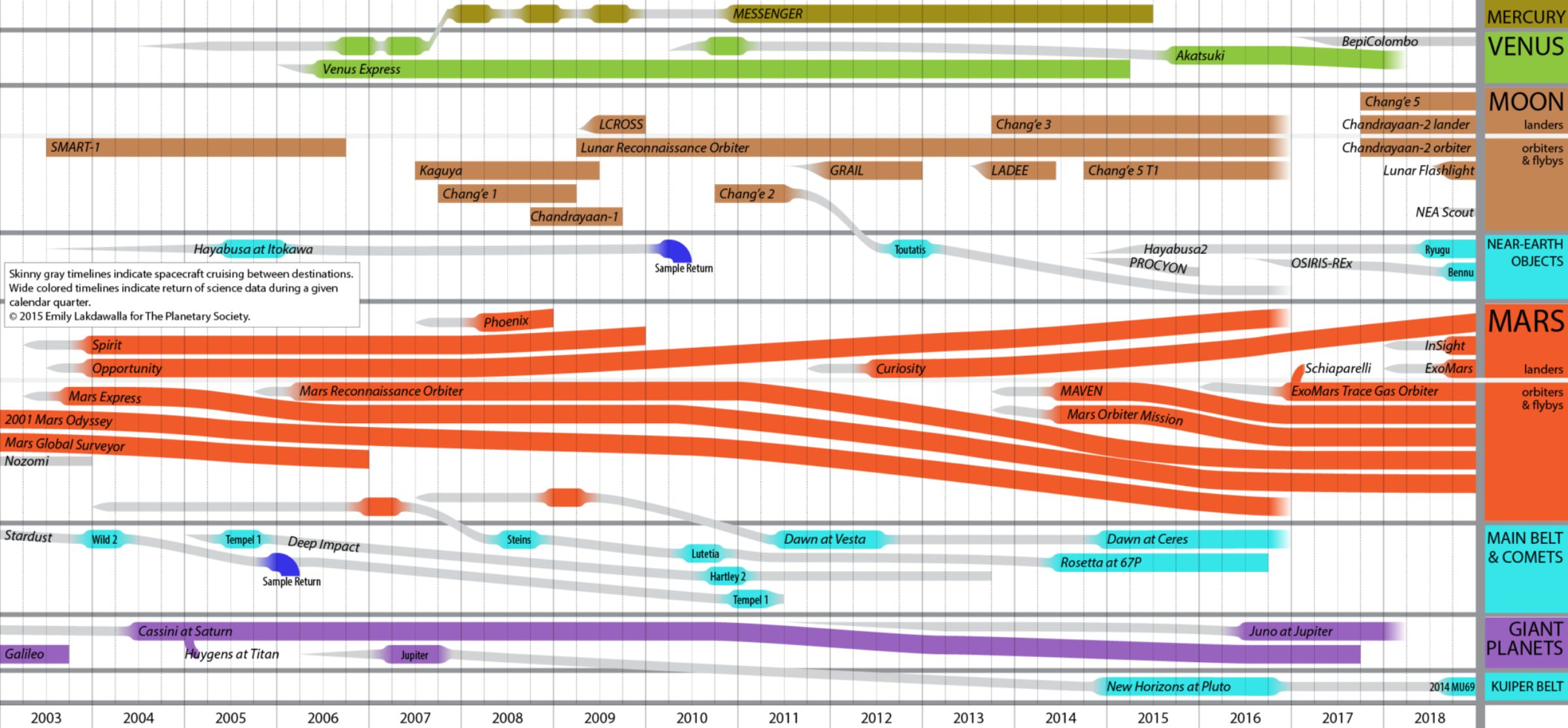

I've tried out a variety of ways of visualizing the state of planetary exploration (including Olaf Frohn's monthly orbital diagrams). Below is something I've been working on periodically for a couple of years. (It was inspired by this chart and discussion.) They're still not perfect (and likely contain errors) but they provide a useful place to start, I think. The skinny, gray bars indicate spacecraft in cruise phase; the bars are fat and colored in any calendar quarter in which they're performing their science mission. This chart starts in 2003 and projects out to the end of 2018.

We are entering 2016 with 15 spacecraft probably actively returning science data from planets, moons, and smaller bodies in the solar system. (I say "probably" because I don't know for sure what the Chinese lunar spacecraft are doing.) Akatsuki is at Venus, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and two Chang'e missions at the Moon, two rovers and five orbiters are active at Mars, Dawn is at Ceres, Rosetta is at 67P, Cassini is at Saturn, and although New Horizons is far past Pluto, it'll be sending back new Pluto science data for most of the year, so I'm counting that as still doing science. Another two missions (Hayabusa2 and Juno) are in their cruise phase; Juno arrives at Jupiter in August. Two (ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter and OSIRIS-Rex) or three (if you count the Schiaparelli lander separately) will launch this year, with their science starting after 2016. The Voyagers and other heliophysics missions don't show up on this chart.

What missions will end this year? Rosetta is the only one with a specific end date, with its landing on comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko in September. Dawn's primary Ceres mission ends in April; it's likely to be kept at work until it depletes its very little remaining fuel, and may not last out the year. Of the seven active Mars craft, four are operating far longer than they were designed to. There's no particular reason to expect any one of them to die this year, but our luck can only hold out so long. I have arbitrarily chosen to fade out the oldest lander and orbiter (Opportunity and Odyssey) at the end of this year, but there's no way to know what the Mars fleet will look like a year from now.

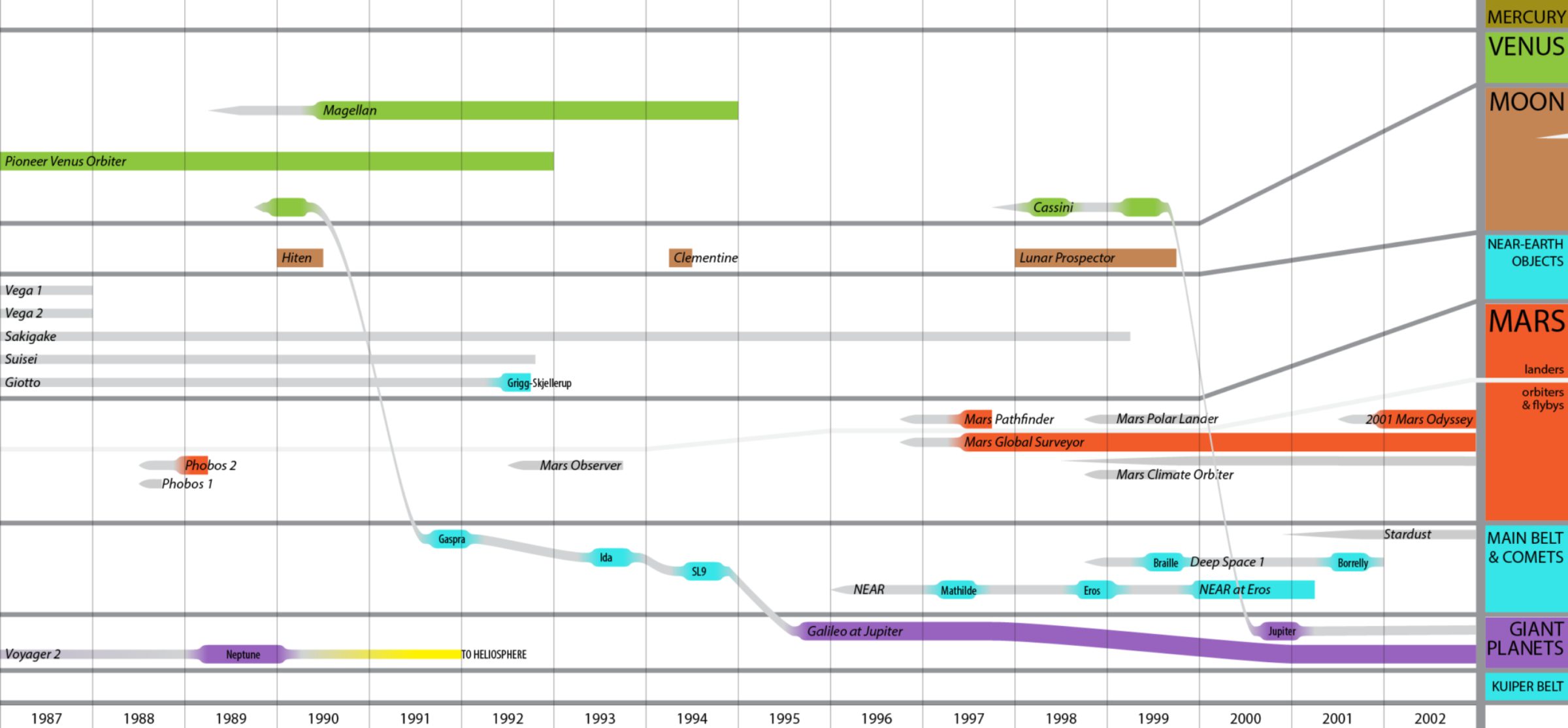

Step back from the chart and look at the robust fat bands of science being done between 2003 and 2018, and now compare it to a similar chart for the previous 16 years. Yes, this chart is complete, as far as I know. Quite a contrast, eh?

I have continued working farther into the past, but am not sufficiently certain about the dates and nature of the Soviet Luna missions to be ready to show you that part of the chart. Some of you may be wondering why the Halley missions are not in the main belt / comet section; it's because Halley was in the vicinity of the orbits of Earth and Venus when the encounters happened, and it makes more sense for the bars for those spacecraft to be near Venus, which two of them flew by.

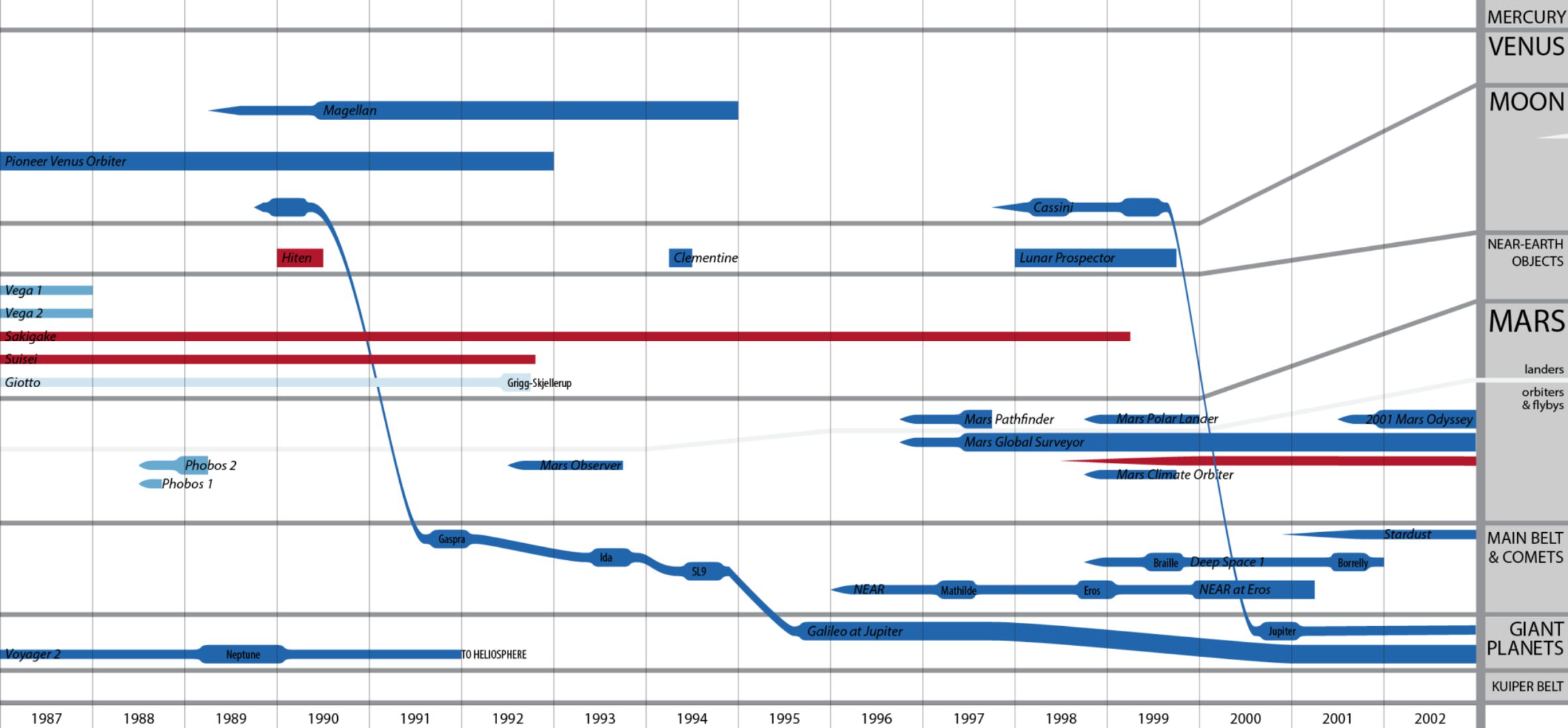

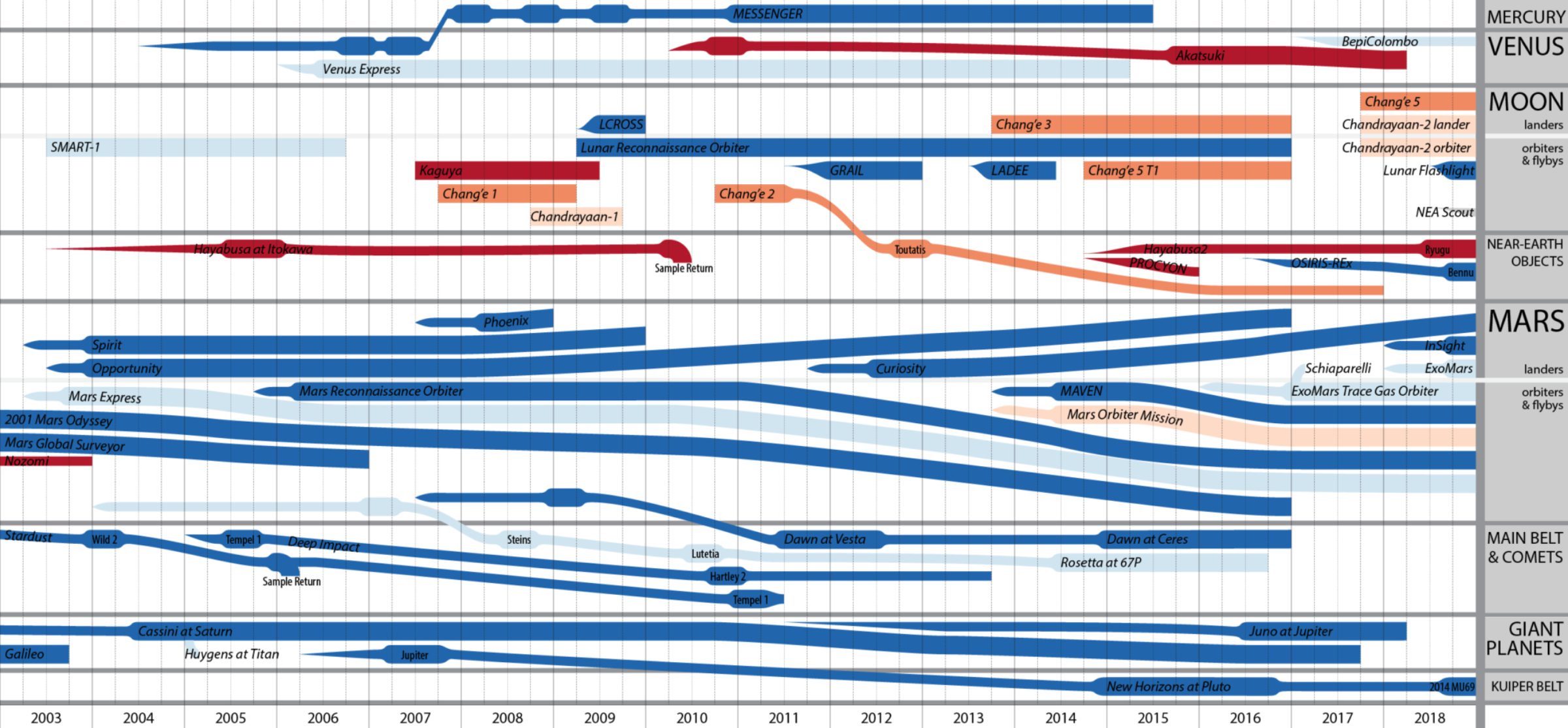

Here's another way of coloring the graphs: according to the agency that launched them. I tried to use a colorblind-safe color scheme on this one, with NASA, Russia, and ESA in shades of blue, and Japan, China, and India in shades of red-orange. I have colored BepiColombo for ESA and Cassini for NASA even though I know those are cooperative missions with JAXA and ESA, respectively -- I need to come up with a better way of signifying those.

Because of the way I've arbitrarily ended a bunch of missions at the end of 2016, there's a falsely sharp cutoff between 2016 and 2017 that won't precisely reflect reality. But some aspects of that cutoff are true: there are no main belt / comet missions that will be active in 2018 and likely 2017 (depending on how long Dawn's fuel lasts); and no more giant planet missions beginning in 2018. There is a period in the beginning of 2018 when the only planetary target from which NASA or ESA will be returning science data is Mars. That's sobering. So enjoy 2016's bounty of space missions, because we're at peak planetary. And please, advocate to #fundplanetary.

Stay tuned over the coming weeks as I take a focused look at active missions, one by one. Happy 2016!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth