Emily Lakdawalla • Nov 08, 2007

Bruce Betts reports from the Phobos and Deimos conference

Planetary Society Director of Projects Bruce Betts and Executive Director Lou Friedman were both in attendance at this week's International Conference on the Exploration of Phobos and Deimos, and Bruce just sent me this report. --ESL

Along with Lou Friedman, I've been attending the First International Conference on the Exploration of Phobos and Deimos at NASA Ames Research Center this week. The conference has been all about Mars' small moons, and current and hoped for missions to explore them. The conference was convened by Pascal Lee of the Mars Institute and a number of other Areolunophiles (ok, I just made that word up).

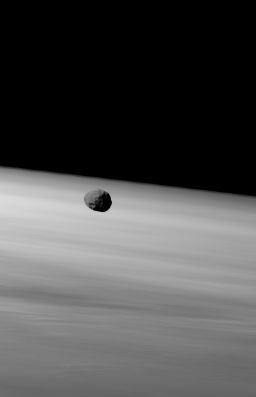

ESA / DLR / FU Berlin (G. Neukum)

Phobos below the Martian limb

In this image, taken on January 22, 2007 on Mars Express' 3,909th orbit, Phobos floats just below the Martian limb. Phobos is the larger and inner of Mars' two moons. Likely a captured asteroid, it is significantly darker in color than Mars. The image has been enhanced slightly to bring out details on the moon.Spectroscopically, Phobos doesn't look like Mars, and does look like some outer main belt asteroids. So, at first it would seem like "game over" for all but the captured asteroid theory (and it is still my favorite). However, since remote sensing instruments like infrared spectrometers only see the very upper surface of the moons, there are arguments that in-falling meteoritic material from the asteroid belt could coat the moons.

It is also still debated if there might be subsurface volatiles on the moon, e.g., water or water rich minerals. Observations show their surfaces to be very dry, but they same types of uncertainties arise about the interiors.

Some nice Random Space Facts about Phobos and Deimos from the meeting:

- They are several kilometers across, and irregularly shaped;

- Phobos is actually significantly bigger, having about 10 times the mass;

- Phobos orbits much closer and more rapidly;

- Phobos' orbit is degrading inward and it will impact Mars in about 100 million years;

- Phobos has unusual grooves whose origin is also still debated;

- Deimos is globally rather smooth and has many craters filled in, possibly from a large impact and its ejecta, but, that's still debated as well;

- we have much better spacecraft observations of Phobos than Deimos;

- they both were discovered by Asaph Hall at the US Naval Observatory in 1877 (they had a nice display of Hall related artifacts at the conference);

- the largest crater on Phobos is named for Asaph Hall's wife's maiden name (Stickney);

- Kepler thought Mars might have two moons because Earth had one and, as far as he knew, Jupiter had four;

- Gulliver's Travels had Mars having two moons long before they were discovered;

- Phobos means fright, and Deimos fear, taken from 15th book of Homer's Iliad;

- Phobos in particular, because of its close proximity to Mars, has variable escape velocities depending on where you are on the moon;

- Both objects have low densities;

- both are quite dark.

Following the summaries of past science, some new data were presented at the conference, both from ESA's Mars Express High Resolution Stereo Camera (HSRC), and from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter CRISM instrument. HSRC has imaged much of Phobos and hopes fill in the gaps when Mars Express starts modifying their orbit, but that will be after the Phoenix landing next May since they'll use their current orbit to support Phoenix Entry, Descent, and Landing. CRISM continues to find Phobos' and Deimos' surfaces to be very dry, and to find two spectral units on Phobos: one associated with the big crater Stickney.

There were also presentations about various possible instruments to study Phobos and Deimos, related science topics like the radiation environment near Phobos and Deimos, and Canadian and U.S. mission studies of possible future Phobos or Deimos robotic missions.

Another piece was introduced on the second day: a discussion of possible future human missions to Phobos or Deimos. Mixed into this were also presentations about missions to near-Earth objects, which also could be applied to Phobos or Deimos. All these missions more resemble docking missions than landing missions because of the very low gravity of these bodies. Among these, it was argued that the Constellation hardware currently planned by NASA could, with small adaptations, could support at least NEO missions, and perhaps Phobos/Deimos.

Perhaps surprisingly, missions to Phobos or Deimos would require less delta v (change in velocity; which basically converts to how much propellant you need) than missions to the surface of the Moon. However, your mission duration is two to three years in deep space. Why do such a mission? Among other reasons, people argue it is a lot easier than a Mars surface mission, eliminating many of the hardest parts (but not all), a good test of a Mars system (a la Apollo 8 or 10), and you get good science at these enigmatic moons and a great location to observe Mars. It will be interesting to see how future exploration of these bodies unfolds, and how our understanding improves.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth