Emily Lakdawalla • Nov 06, 2007

A fifth planet for 55 Cancri

There was a big extrasolar planet announcement today. I'm young enough that, for me, it's always been the Space Age. But there have been some major revolutions in space science in the time I've been around, and one of those is extrasolar planets. I had a Time-Life series of books on science that I read and reread growing up, and I remember reading about how it was possible that at least some of the other stars in the galaxy also hosted systems of planets, but that no one really knew whether planets were common or if our solar system with its nine planets and asteroid belt was relatively (or entirely) unique. This state of affairs persisted until I was in college, when the first exoplanet discoveries were made. Since then, more than 200 exoplanets have been discovered. Because of the way that exoplanets are detected, most of the ones that have been discovered are very large planets in very small, often very elliptical, orbits. Really big planets in really elliptical orbits are about as different as a planetary system can be from our own solar system.

A few times a year, some discovery is announced of a planet that is closer to being Earth-like; it's a smaller planet, in a more circular, more distant orbit, or some such thing. Earth-like planets are very difficult to detect, for several reasons. Mostly, they're small and relatively distant, so it takes a fairly long time-series of observations with very sensitive instruments to detect them. Today's announcement was not about the discovery of an Earth-sized planet.

The announcement was about a planet orbiting 55 Cancri, a main-sequence star, like our own star, but a little smaller and hence a little fainter. This star system was already known to have four planets orbiting it. The announcement today was about a fifth planet (found in between the previously known third and fourth planets), giving 55 Cancri more planets than any known star system except our own. Here's a summary of 55 Cancri's planets:

| Planet | Distance (AU) | Orbital period (days) | Mass (Jupiters) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 55 Cancri e | 0.038 | 2.8 | 0.03 |

| 55 Cancri b | 0.115 | 14.7 | 0.82 |

| 55 Cancri c | 0.24 | 43.9 | 0.17 |

| 55 Cancri f (newly discovered) | 0.781 | 260 | 0.14 |

| 55 Cancri d | 5.77 | 5,200 | 3.84 |

What's more exciting is that the newly discovered planet orbits within the "habitable zone" of the star, the region in which surface conditions on a solid-surfaced body could be amenable to the persistence of liquid water and, possibly, Earth-like biology.

Because that's what this extrasolar planet business is really all about. Exoplanetary systems are exciting in their own right -- just imagine, there are hundreds and thousands of star systems out there, each of which probably contains as much diversity as our own star system and its planets and moons. That's pretty fascinating to imagine. But the search for extrasolar planetary systems really comes down to the question of whether there are worlds like ours out there, and if those Earth-like worlds also contain life. Is our environment unique? If it is, then Earthlike life is necessarily unique, and we may be alone in the universe. But if Earthlike environments are commonly or even just occasionally found elsewhere, then there may be life elsewhere.

So why get so excited about this newly discovered world, which is probably much more like Neptune than it is like Earth? (The new planet is twice the mass of Neptune, or half the mass of Saturn, almost definitely a gassy or icy giant, almost certainly not a solid-surfaced world.) Well, all the big planets in our solar system have moons, some of them pretty big moons. So there's no reason not to believe that 55 Cancri's five planets each has its own retinue of moons, a few of them pretty big. The pretty big moons would be made of rock and ice, just like the moons in our solar system, and if they are at the right distance from their star, and especially if they get a little internal energy generated by tidal interactions, there could be worlds with oceans and geothermal activity and chemicals floating around and all kinds of neat stuff. Just the right sort of environments for life.

Still, before we go searching for life elsewhere in the universe, it would behoove us to perform a good search in some of the more hospitable places in our own solar system. There's nothing else in the "habitable zone" of our star except us and Mars. We ought to check Mars carefully to see if anything used to thrive there. And we can check the icy worlds of the outer solar system, which are too far outside the habitable zone to have life on their surfaces, but which could potentially harbor life in their interiors. But if we find no non-Earth life in our own solar system, we can broaden the search to these habitable environments around other stars. Are we the only life in the universe? It just seems unlikely to me that we are. We ought to check!

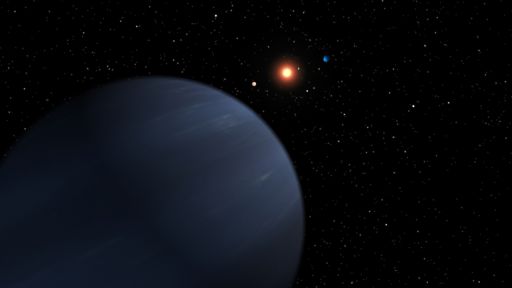

Artist's concept of 55 Cancri's fifth-discovered planet As of November 2007 the nearby sunlike star 55 Cancri was known to have five large planets in near-circular orbits around it, more than any other star except the Sun. This image shows the fifth-discovered planet (fourth in distance from its star), which is about half the mass of Saturn or twice that of Neptune. It orbits within the "habitable zone" of its star at a distance of 116.7 million kilometers (72.5 million miles), slightly closer than Earth to our sun, but it orbits a star that is slightly fainter. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech |

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth