Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 17, 2013

Conversations with an interplanetary spacecraft: "Hi, Juno!"

There was so much news at the American Geophysical Union meeting last week that I am still drowning in material. One of the many press briefings concerned the scientific data gathered by the Juno Jupiter orbiter when it flew past Earth in October. This was so cool.

The Earth flyby represented the first opportunity for many of the science instruments to be used on a planetary target. Earth is a very different planet from Jupiter, though. Not all of Juno's instruments could "see" the phenomena they were designed to study. Earth lacks the strong magnetic field of Jupiter, so it's dim to fields-and-particles instruments, but visually it's a much brighter target than the optical instruments were intended for. Still, most of the science instruments gathered data, and some of that data will be useful to calibrate and check the performance of the instruments in space.

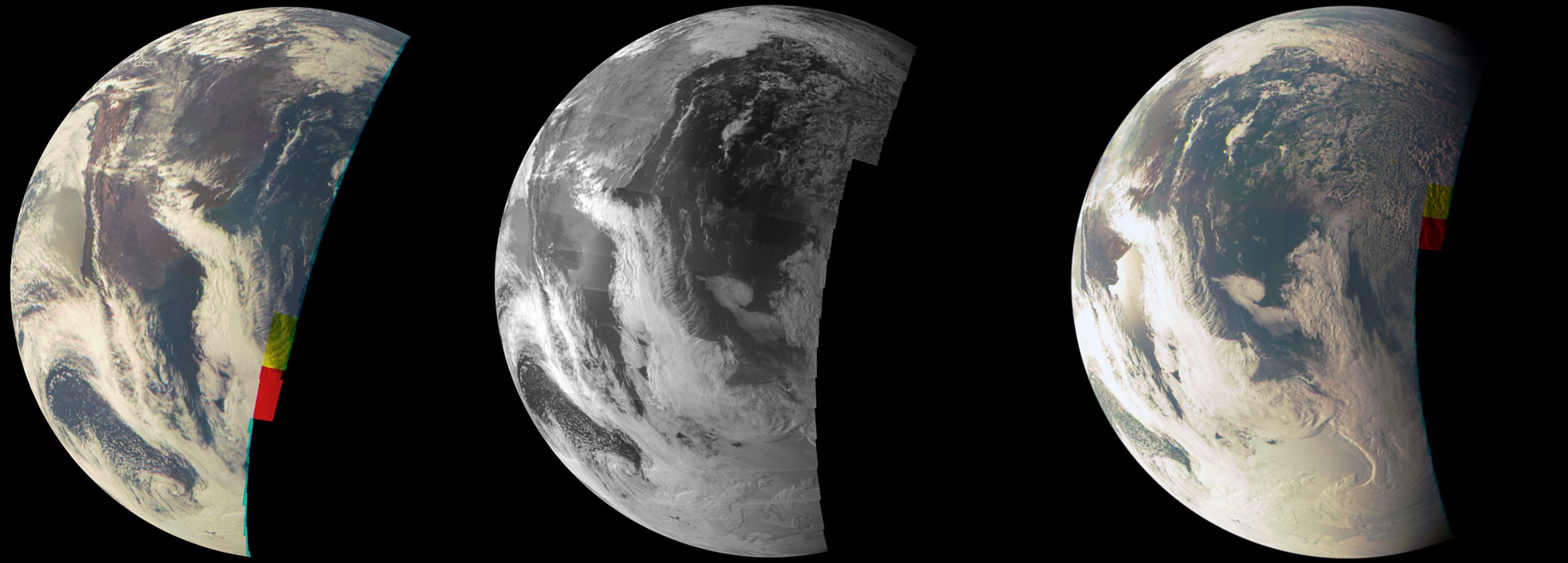

But the science team took data on our home planet for other reasons. It's fun to ask the question: if this flyby were of an alien planet, could we detect the presence of life down there? Photos of the whole Earth are not terribly suggestive. Life isn't obvious in photographs of the multicolored surface of Earth unless you happen to be expecting chlorophyll's distinctive dark appearance in visual wavelengths and bright appearance in the near-infrared:

However, when Juno passed over Earth's nightside, Junocam achieved a clear detection of life on the surface, shining its light out into space. This photo, of the night lights of Cape Town, was especially poignant in light of the recent death of Nelson Mandela.

Another camera on Juno, the star tracker, caught the twirling dance of Earth and the Moon. This sequence is heavily processed because the star tracker was really not intended for imaging an object as bright as Earth, and it is also not a color camera -- the color here is simulated. It's still a cool set of images, one I was happy to add to my list of pictures of Earth from deep-space craft.

Earth and Moon Seen by Passing Juno Spacecraft When NASA's Juno spacecraft flew past Earth on Oct. 9, 2013, it received a boost in speed of more than 8,800 mph (about 7.3 kilometer per second), which set it on course for a July 4, 2016, rendezvous with Jupiter. One of Juno's sensors, a special kind of camera optimized to track faint stars, also had a unique view of the Earth-moon system. The result was an intriguing, low-resolution glimpse of what our world would look like to a visitor from afar.Video: NASA / JPL

But neither Junocam nor the star tracker is a science instrument. Juno is a mission designed to study the deep interior of Jupiter and also its intense plasma environment and magnetic fields. Earth's performance in this area is pretty weak, which actually presented an opportunity to the Juno team. Could intelligent life on Earth produce a signal strong enough to be picked up by the instruments designed to study Jupiter's fields and particles? There are lots of entities all over Earth producing radio emissions, creating a murmuring informationless background of noise to Juno's instruments. But what if there could be a coordinated effort to send a signal out to space that Juno's instruments could detect?

They tried that through the "HI Juno" project, coordinating volunteer ham radio operators all over the world -- every continent, even Antarctica, participated -- to press and release their telegraph keys in unison, broadcasting a simple, Morse-code "HI" to the Juno spacecraft. The spacecraft rotates twice a minute, so they coordinated the hams to broadcast their Morse "dits" in a sort of slow motion: each "dit" was represented by a key-down lasting thirty seconds, each gap between dits another thirty seconds.

The result is quite wonderful. Juno detected some of the signal six times, and three times it received intelligible, complete Morse-code "HI"s.

When I listened to that bit of signal just barely rising out of Earth's background noise, I was immediately transported. The dit-dits took me back to the living room of my grandparents' tiny house in Walla Walla, Washington. There was a little closet-size room off to one side, completely and entirely wallpapered in QSL cards, an ornate morning-glory Victrola record player on a shelf in the corner, and an array of radio equipment on wide shelves against both walls. Morse code and radio chatter emanated from that room at all hours. This was my grandfather Pat Stewart's ham shack. His callsign was W7GVC. I couldn't locate a photo of the ham shack, but here he is in his "radio museum" -- that is, the basement. He canvassed flea markets all over the Pacific Northwest to amass a collection of radio equipment, and brought many a decrepit husk of a wartime radio back to life in his basement workshop.

I didn't pick up the ham radio bug from Grampa, nor did I ever tinker with vacuum tubes and wire coils with him. His wife Anna, my grandmother, spent hours upon hours teaching me needlecraft, with the chatter of ham operators and Morse code a constant murmur in the background, a noise that we weren't a part of. I do wonder if things would've been different if I had been a boy. It's too late for me to learn from him now -- he died while I was in graduate school.

But there are girls learning about amateur radio now, and a couple of them are featured in this wonderful, brief documentary that JPL put together about the "Hi Juno" project.

Grampa would've loved this. Rest in peace, W7GVC.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth