Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 17, 2015

Worth the wait: First public release of Rosetta science camera images of comet 67P

Finally! It has been a long wait, but so worth it: the Rosetta OSIRIS science camera team has delivered the first pile of data from the rendezvous with comet 67P to ESA's Planetary Science Archive. I have spent a good chunk of the last three days playing with the data, and it's spectacular. Most cameras that have been sent to the outer solar system have detectors that are about 1000 pixels square; the OSIRIS detectors are 2048 by 2048, and breathtaking in their detail.

The data release covers the period up to September 16, 2014. This was during Rosetta's approach to the comet and the very beginning of its global mapping phase. During this time, Rosetta approached from a distance of 40,000 kilometers to only 29 kilometers away.

ESA provides a really cool browse tool that lets you get a feel for what's in the data. You can browse all of the Rosetta data from both OSIRIS science cameras and the Navcam engineering camera at this site. But, geek that I am, I want more information at a glance, so I set out to build my own browse pages to the data. Here they are, for your pleasure:

- Far Approach Trajectory (July 2-August 6, 2014)

- Close Approach Trajectory (August 6-September 10, 2014)

- Global Mapping Phase (September 10, 2014-)

- Also useful may be this Information about the OSIRIS science camera, including an explanation of the filters

One of the first things people want to do with archival science data is to create color images from several black-and-white images captured through different-color filters. It turns out to be very hard to do such color processing with this data set, because the comet spins fast and is very lumpy. The perspective shifts from one image to the next, making it extremely difficult to align the different channels. Fortunately, there are experts like Daniel Macháček who can handle the challenge:

Another fun image processing activity is to create animations from time-series of images, like this absolutely stunning one assembled by "Herobrine." If you click the image, it'll enlarge to 840 pixels wide and 11 megabytes; follow the link in the caption, and you'll get it at 1920 by 1080 and 63 MB -- but believe me, it is very, very worth it.

This is also a good example of how much jet detail there is in long-exposure images. The images I have uploaded to my index pages are all 16-bit, meaning that there is rich information available in the shadows if you open them in an image processing program like Photoshop that can handle 16-bit data.

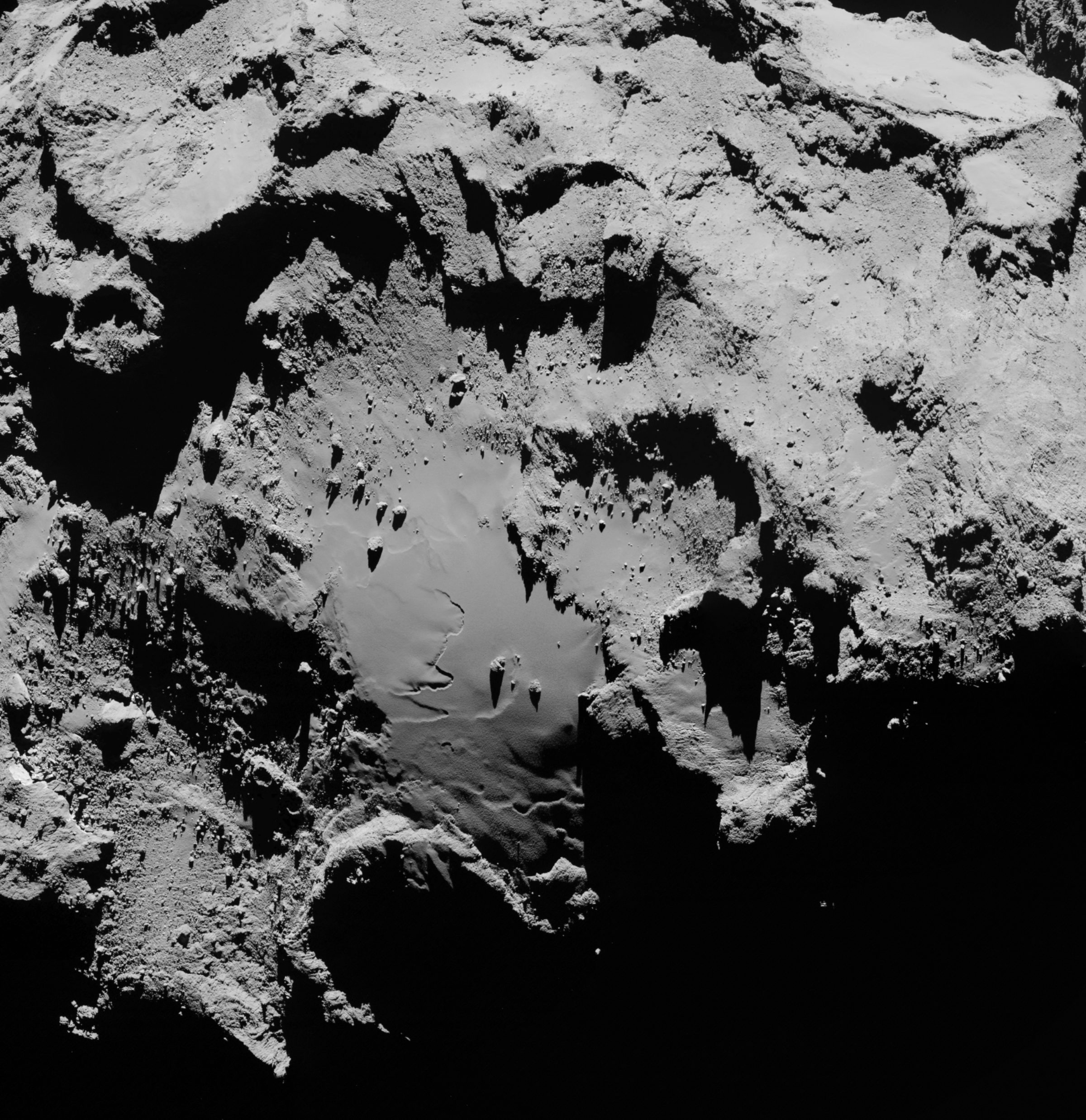

There is a lot of fun to be had making mosaics, like this one assembled by Justin Cowart. It is 3500 pixels square -- again, worth enlarging to enjoy all the detail.

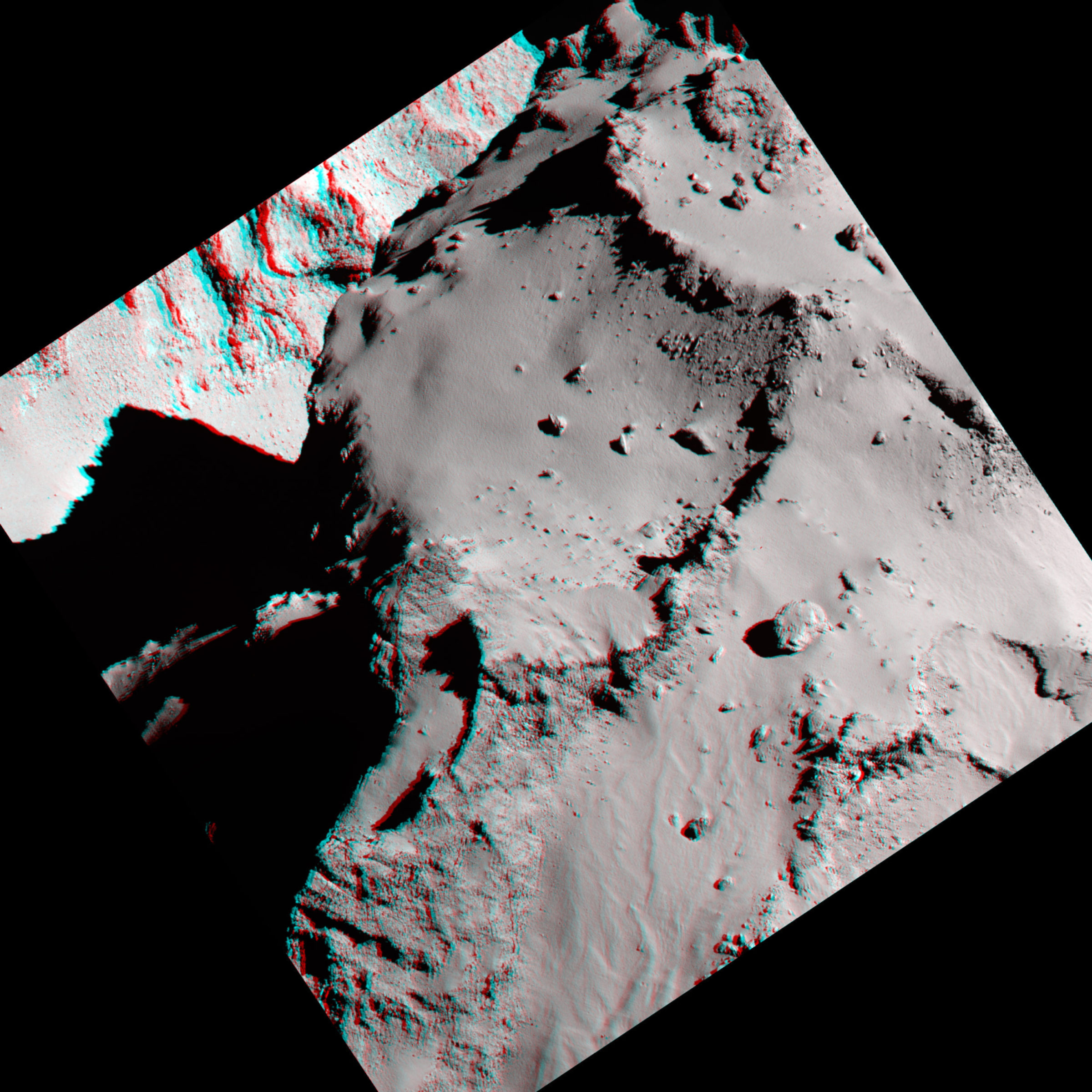

I found it frustrating that there was so much motion from frame to frame that color image processing is difficult, but there's a silver lining to that cloud. Parallax between similar images allows you to generate 3D views. So every time Rosetta captured a color imaging sequence -- multiple photos right after each other taken through different filters -- it also captured stereo data. For the color imaging during the closest, global mapping phase, I found that I could take the first and last photo from pretty much any imaging sequence and turn it into a depth-rich 3D view. Here's one:

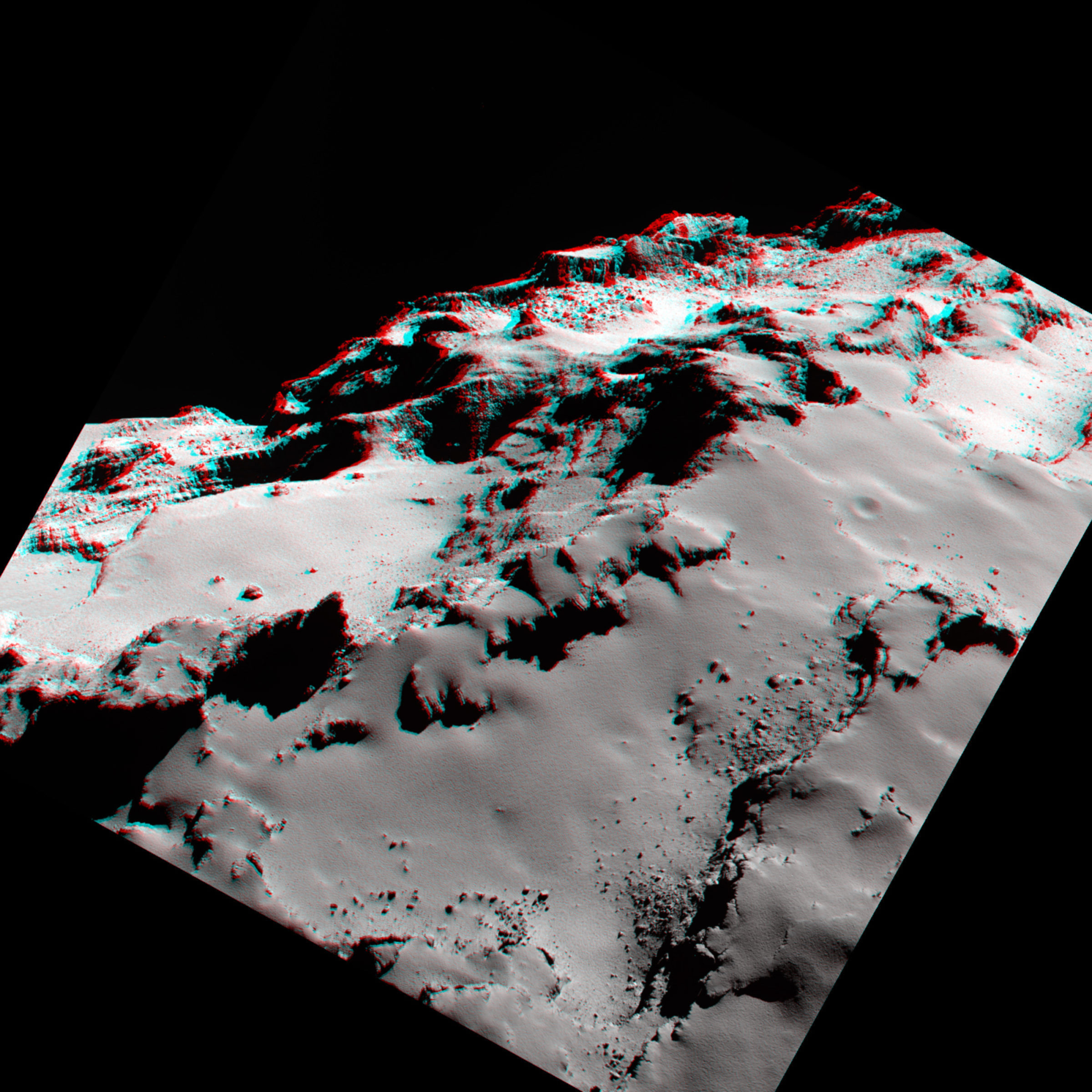

Here's another:

I made both of those 3D images by grabbing a pair of pictures nearly at random from the color observations that OSIRIS performed with its narrow-angle camera during the global mapping phase. There are dozens of possible stereo pairs available to play with, and yet the OSIRIS team has only released a week's worth of data from the global mapping phase. The nearly 5,000 images in this data release are only a tiny taste of what's to come.

It took me three days to write this post because I ran into several issues while creating the image browsing pages. First among them was a lack of metadata tables providing useful information on when and from what distance and why OSIRIS images were taken, but fortunately BjörnJónsson's IMG2PNG software can spit out text-formatted metadata as it's processing images, and I used that to build my own table of metadata. The second problem is that the three cameras -- OSIRIS narrow-angle, OSIRIS wide-angle, and Navcam -- have data that is flipped or rotated in different ways. I ended up having to process the entire data set multiple times in order to orient all the images in the same direction and take out the mirror-flipping of the OSIRIS narrow-angle camera data. But that's all done now, so if you browse my data pages you'll find 16-bit data in all their glory, all oriented the same way. (Having said that, it's quite likely that in the process of flipping and rotating 8,000 pictures, I made mistakes. Caveat emptor.)

I have barely scratched the surface of the OSIRIS public data set -- and yet, the data that have been released so far are, at a minimum, 15 months old. Hopefully this is just the first of many stunning data releases for Rosetta OSIRIS.

And now, to go process more 3D views of our solar system's best-studied comet....

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth