James Davenport • Dec 08, 2017

An exoplanet-hunting space telescope turns and takes a photo of Earth

This article originally appeared on James Davenport's Medium blog and is reposted here with permission.

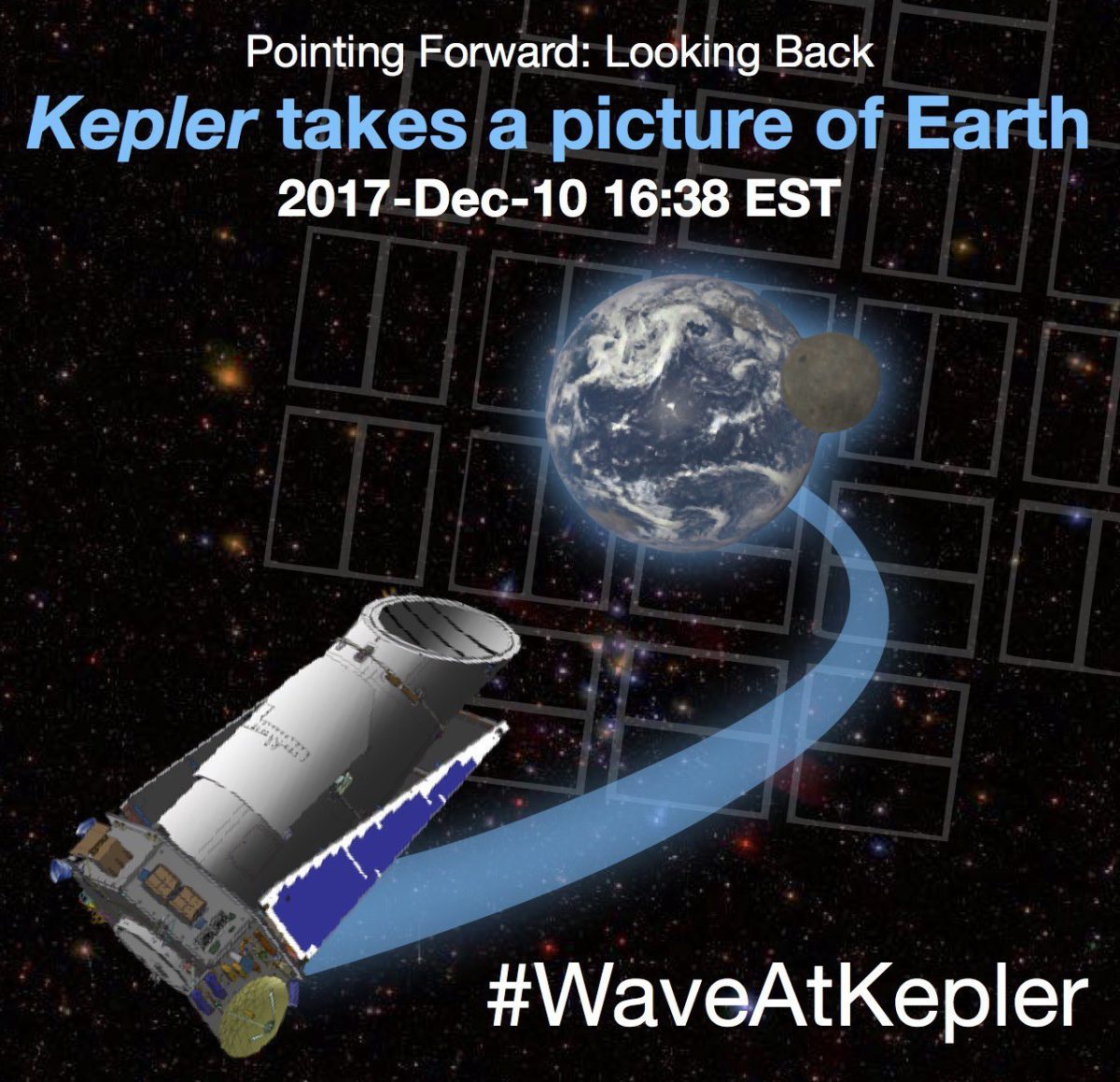

In the early afternoon this Sunday, December 10, I will go out onto my back porch and wave at the sky. Since I live near Seattle it’s likely to be cloudy in early December, but that hardly matters — the thing I’m waving at is almost 100 million miles away. December 10 is the day that Kepler, NASA’s prized exoplanet discovery telescope, will finally turn back and take a picture of the Earth.

This is no casual selfie. Erin Ryan and I submitted a proposal to NASA almost a year ago to the day (Dec 15, 2016) to capture this moment, and we didn’t find out that the telescope was going to attempt the observation until six months later. I first became excited about this idea a year before that, when I realized it was even possible for Kepler to see Earth. This is the pace you expect when you’re dealing with scientific resources in outer space: ideas can take years to come to fruition.

Kepler is about the size of a pickup truck, and was designed to find planets orbiting around other stars using the “transit method”. Everything about the facility was engineered around that single goal: the field of view is very wide to survey as many stars as possible, the camera takes fairly long exposures (usually 30-min), the pixels are large (a low-res image), and it stares at the same field continuously so the scene doesn’t change. As a result, the image quality is not “beautiful” like we’re used to seeing from missions like Hubble, but the time-series data used for transit searches is exquisite.

Originally Kepler pointed for over 4 years at a single field, a region visible in the Northern hemisphere during the summer near Vega. To do this, the spacecraft required total control over its orientation in 3-dimensions, like an airplane’s pitch, roll, and yaw. However, this mission ended in 2013 when 2 of the 4 onboard reaction wheels failed (one was a spare), and the telescope could no longer be pointed with precision at the Kepler field.

The folks at Ball Aerospace (who built Kepler) and NASA devised a clever extended-life mission: point the telescope at multiple fields for shorter spans of time. Using a combination of thrusters and the solar wind, the spacecraft is kept nearly as stable as in the original mission, but can only hold its position steady for about 80 days at a time. Importantly, the new fields are all spaced along the ecliptic plane. While this new mission, called K2, was a loss for people studying years-long planet orbits, it opened many new doors. Including taking a picture of Earth!

The Kepler spacecraft is in an “Earth trailing” orbit, traveling around the Sun slightly slower than the Earth, and therefore constantly drifting away from us. In the normal K2 program, the telescope looks “behind”, i.e. away from Earth. From this viewpoint, the K2 mission has studied over 200,000 stars, more than doubling the original Kepler sample, spotted asteroids whizzing past, tracked the orbits of the moons of Neptune, and discovered hundreds of new extrasolar planets. However, occasionally the telescope is oriented “forward” in the direction of the Earth’s orbit. This is usually done (as in Campaign 9) to search for “microlensing” signals, or to overlap with a previously studied field (as in the upcoming Campaign 16). In this orientation the Earth is visible by Kepler for a few days, and gives us the chance to capture this picture of our home from a distant vantage point.

The picture from Kepler will not show high levels of detail of the Earth’s surface. To get an idea of what Earth will look like in Kepler’s field of view, here is an image Kepler captured of Mars earlier in 2017 (in Campaign 12).

Interestingly, a lens-flare-like property of the Kepler optics for bright objects means there will also be a “ghost” image of the Earth, reflected across the field of view. You can see the “Ghost of Mars” from Kepler here.

On Dec 10, the Earth and Moon should both be visible within the field of view, and will likely be a bit brighter than Mars. Leading up to the Dec 10 photo, Kepler/K2 will track the Earth as it moves towards the edge of the field of view. A small strip of pixels will gather brightness measurements as the Earth rotates, which we hope to use as a training set for studying the rotation of planets around other stars. The grand image will then be snapped on Dec 10, but the data won’t be downloaded for another couple months as K2 continues to study the stars in this field as part of normal operations.

Taking photos of the Earth using far-flung spacecraft has become something of a tradition for NASA. These pictures can reach iconic status — TIME magazine rates “Earthrise” as one of the 100 most influential images of all time, for example. For me, the “Pale Blue Dot” image taken from Voyager 1 strikes the deepest chord. This picture shows the Earth as nothing more than a faint dot, a single pixel in an image. The entirety of humanity becomes reduced to a fading speck as Voyager leaves our Solar System. Similar images have now been taken from many NASA missions, including a stunning mosaic from Saturn, and Earth as the “Evening Star” from the surface of Mars.

Here are the official versions for several of these looking-back-at-Earth photos: “Earthrise” from the Moon, “Pale Blue Dot” from beyond Pluto, “The Day the Earth Smiled” from Saturn, The Evening Star from Mars, Earth and Moon from Mars.

Voyager gathered our first detailed knowledge of the outer solar system, and the first views of Earth from the doorstep of interstellar space, some 4 billion miles away. While not as distant, Kepler’s mission is no less profound. We have learned for the first time that nearly every star in our Galaxy hosts a planet, and many of them are small and dense like our own. This is a monumental leap forward in our search for life and our place in the cosmos.

Amazingly, Kepler has also pushed the frontiers of science in many areas besides exoplanets, including asteroseismology, stellar rotation, stellar magnetic activity, supernovae, and discovering many new types of variable stars — some which still defy explanation! With each of these discoveries, each of the thousands of scientific of papers written, people have invested years of time. Many young scientists like myself have built much of their careers on the data and discoveries that Kepler has provided.

The Kepler spacecraft is now running low on fuel, and the K2 mission is not expected to extend far beyond this year. That makes this image especially personal: a reflection on the past 8 years of my career, on the choices I made mid-PhD to drop what I was working on and pursue an entirely different thesis project, on the friendships and journeys I have been on because of this mission. The final Kepler/K2 Science Conference this summer ended with a “Farewell” of sorts, which was an emotional conclusion for the researchers in attendance. The image we’ll capture in December, however, is for everyone: scientist and citizen alike.

For more information, visit WaveAtKepler.space

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth