Travis Rector • Dec 08, 2015

Colors in Planetary Imaging

If you’re reading this article, you probably love astronomy images. When looking at an image of, say, a galaxy, have you ever wondered to yourself, “Is this real?” or maybe “Is this what it really looks like?” The first question is easy to answer. Yes, everything you are seeing is real. Unless it is “space art,” these images are of real objects in outer space. They aren't creations of a graphic artist's imagination. But answering the second question is not as simple. How a telescope “sees” is radically different than how our eyes see. Telescopes give us super-human vision. In most cases they literally make the invisible visible.

Let’s look an example. The picture above captures the famous Horsehead Nebula, which gets its name from the distinctive dark shape at the center of the image. It is part of a large nebula in the constellation of Orion. The image was taken with an advanced digital camera from a telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in southern Arizona. This is what the telescope and its camera can see. But let’s pretend you had the ability to board a spaceship and fly to the Horsehead Nebula – what would you see? After a journey of more than a thousand light years, you look out of the window of your spaceship at this same scene. You’re now at a distance of one hundred times closer than before, when you were standing on the Earth. Here’s your view now.

You’d see some of the brighter stars but none of the dust and gas in the nebula, including the horse head shape. Why?

Three Things a Telescope Does

To better understand what’s going on, it helps to know what a telescope does. Just as a pair of binoculars can make the upper-level seats in an arena almost as good as courtside, a telescope can make a distant object appear much closer. But a telescope does more than this. It doesn’t just magnify an object; it also amplifies it. It makes something faint appear much brighter.

Some people think the reason why a telescope can see objects our eyes can’t is because it magnifies something that is too small for us to see. And this is often true. But the Horsehead Nebula is actually not that small. The fields of view of these images of the Horsehead are about twice the size of the full Moon on the sky. You can’t see it because it is too faint, not because it is too small.

So why couldn’t you see the Horsehead Nebula even if you were much closer? For objects that appear to be larger than a point of light (e.g., galaxies and nebulae, but not stars), how bright it appears has little to do with how far away it is. Moving closer to it will make it bigger, but not brighter. This may seem counterintuitive, but you can try it at home. Walk towards a wall. As you approach you’ll notice that the wall is getting bigger but otherwise is the same brightness. The same is true of the Horsehead Nebula. If you can’t see it with your eyes while standing on Earth, you still won’t see it from your spaceship.

Why then can a telescope see it? A telescope offers several advantages over our eyes. As marvelous as the human eye is, it’s not that well suited for nighttime observing. First, our eyes are tiny. The opening that allows light to enter, known as the pupil (the black area at the center of the eye), is only about one-quarter of an inch wide when fully open.

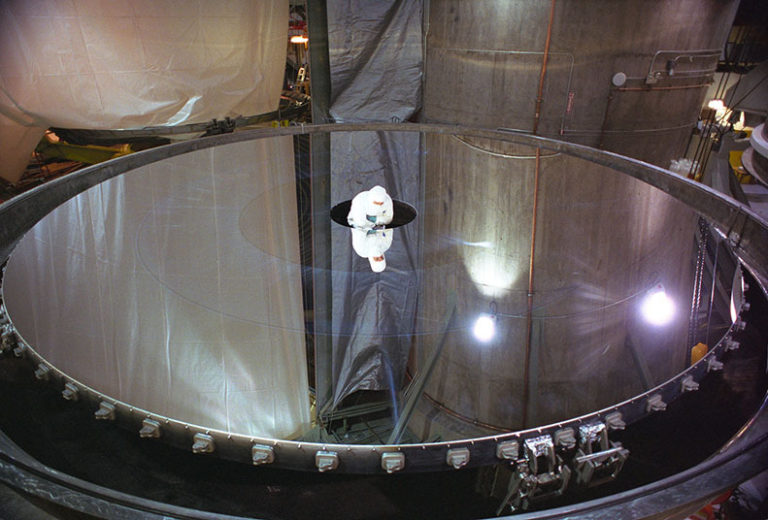

In comparison, the mirror that collects light for the Gemini North telescope, one of the professional observatories atop Mauna Kea in Hawai‘i, is over 8 meters across. What this means is that, at any given moment, this mirror is collecting more than a million times more light than your eye. The more light you collect, the fainter an object you can see.

Human eyes also don’t collect light for long. Our eyes function like a video camera, taking images about 30 times every second. So the exposure time for each image captured by the human eye is only one thirtieth of a second. With digital cameras attached to the telescope we can collect light for as long as we like. The longer the exposure, the more light the telescope collects.

Typically a single exposure is not more than 10 to 20 minutes; but multiple exposures can be added together to make a single image with an exposure time that is, in effect, much longer. To create the most sensitive image ever made, astronomers collected over 50 days worth of observation time with the Hubble Space Telescope of a single portion of the sky. Known as the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field (XDF), this image represents a cumulative exposure time of about 2 million seconds!

The human eye is complex. It isn’t as sensitive to faint light; and it only detects amounts that are above a certain threshold. To prevent confusion, our brain filters out the “noise” below that level. In comparison, modern electronics detect nearly all of the light that enters a telescope’s camera, even if it takes hours to collect the light. All of these factors enable telescopes to go far beyond the limits of human vision. The faintest objects in the XDF are about 10 billion times fainter than what the human eye can see.

Finally, the Universe and the amazing objects in it glow in other types of light – from radio waves to gamma rays – that are impossible for our eyes to see. It’s taken the ingenuity of scientists and engineers over the course of many decades to develop our abilities to capture the views of the Universe that we enjoy today. Without these technical tools, many phenomena and objects would simply be invisible to us entirely.

Show your True Colors

It's no exaggeration to say that telescopes give us super-human vision. Nearly every astronomical image contains objects too small and/or too faint for us to see. And these images often show us kinds of light our eyes can’t detect at all. So how do astronomers take what the telescope sees and convert it into something we can see? This is a question that has challenged astronomers and astrophotographers for decades. There’s no simple answer because it depends on the telescope and camera, the type of light, the filters used, and the object observed.

Each image is therefore made in its own way. Fortunately professional observatories usually provide information about how the image was made. When reading the caption or background information about an image it might be described as shown in “true color,” “false color,” or maybe even “pseudocolor.” What do these terms mean?

False color and pseudocolor are phrases that unfortunately have not been used consistently. What’s important to know is that these terms do not mean that the image is not real. They simply mean that color is used to show objects in a way that’s different than your eyes. On the other hand, “true color” usually means that what you’re seeing is an attempt to represent how the object would look to your eyes, albeit if they were more sensitive. Astronomers can make color images using filters that are reasonably close to the cones in our eyes. These images are often labeled as true color even though color has an ambiguous meaning for objects too faint for our eyes to naturally see. This is the case for most of the objects in space.

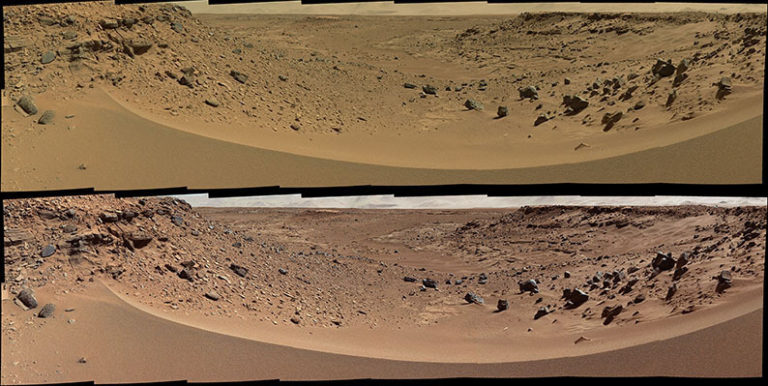

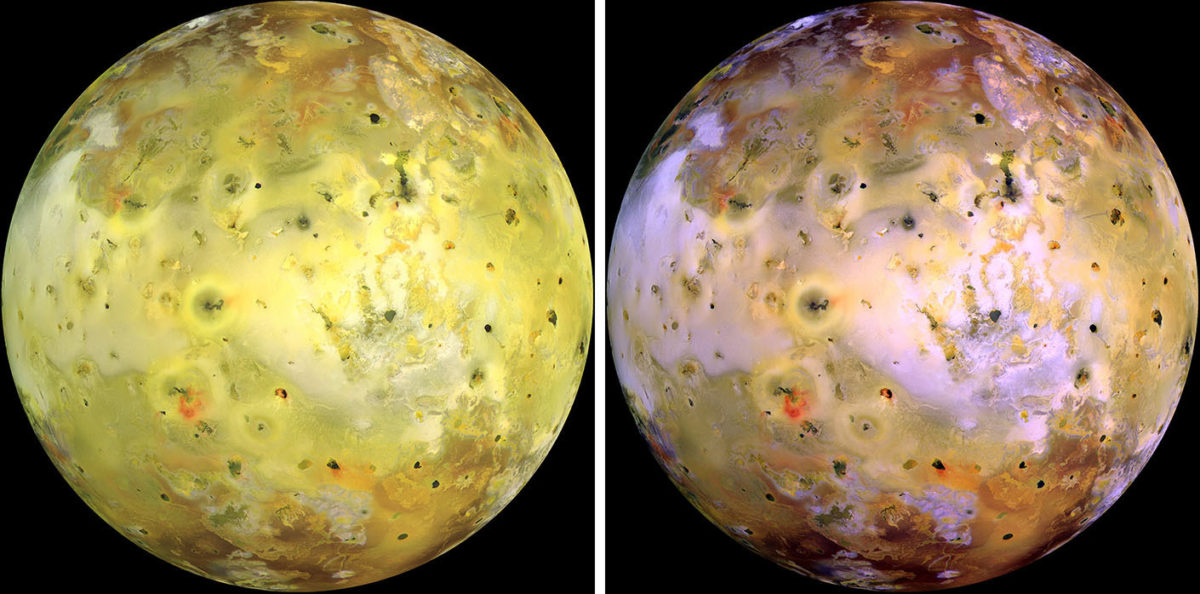

However, true color is a realistic goal for bright, sunlit objects such as planets and their moons. Spacecraft that land on other planets often carry additional tools for color calibration to account for the effects of the atmosphere. Just as our blue skies (or orange skies at sunset) can change the apparent color of an object, the same effect occurs on other planets with atmospheres. The thick yellow atmosphere of Venus and the dusty brown air on Mars affect the apparent color of the planets’ surfaces. To take this into account, swatches of known color are placed on the spacecraft. By taking pictures of these color swatches with the onboard cameras, the color images from those cameras can be calibrated to show what you would see if you were there. Color-corrected images can also be made to show the “intrinsic” colors of the surface – that is, as it would appear if the Sun and sky were white. Scientists use these intrinsic colors to help identify the kinds of rocks and minerals that are on these distant worlds.

Scientific and Beautiful

Within the confines of a blog post, we’ve tried to explain what a telescope does and the challenge of making astronomical images with the data they produce. It is a fundamental challenge because our telescopes can show objects in ways that our eyes cannot. That is of course the reason why we build telescopes! There would be no point to building machines like Gemini, Hubble, and Chandra if they didn’t expand our vision.

The images you see are intended to show the science that is being done with these telescopes. The reputations of the observatories, and the scientists who use them, are tied to the truth of what’s in the image. No self-respecting scientist would intentionally do something to create a misleading image from his or her data. Think of a doctor who has taken an X-ray of an ailing patient. They may use techniques to enhance the picture so that more detail can be seen, but they would never add or remove a fracture in a bone. The same is true here.

There is an artistry to making these images, but ultimately the goal is a scientific one: to share with people the discoveries astronomers are making with these fantastic machines of exploration. With advances in telescopes, cameras, and image-processing software, we continuously improve our ability to see planets, stars, and galaxies. Though each image is a representation, it offers a real view into our real and fascinating Universe.

To learn more about how astronomers make images we invite you to read our new book, also titled “Coloring the Universe.” The book has over 300 images, and each image has its own story as to how it was created, what it shows, and what scientists learn from it. We hope that, by reading the book, people will better understand and appreciate these beautiful images. The book is available online from several major book sellers.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth