Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 22, 2007

Iapetus!

Sorry it has taken me so long to get to these images. I guess it was too much for me to swallow all at once! On September 10, Cassini flew by Iapetus. Two weeks ago, on the first day of the Division of Planetary Sciences meeeting, several of the science teams released beautiful products that give an early look at some of the science results from the encounter.

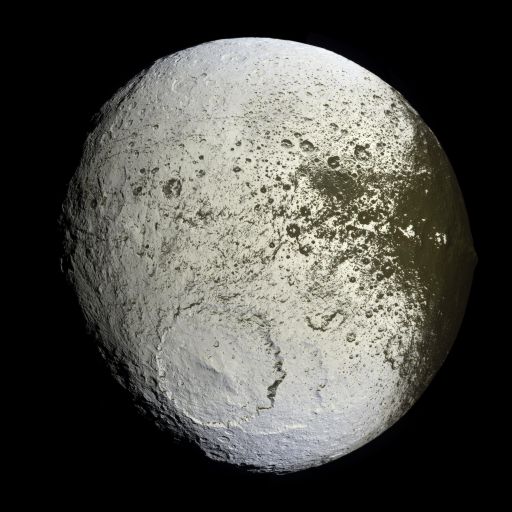

The images are spectacular, of course. I've already posted an amateur grayscale version of this one; here, now, is an enhanced-color view of the trailing side of Iapetus in all its detailed glory.

NASA / JPL / SSI

Iapetus' trailing hemisphere

As Cassini departed Iapetus on September 10, 2007, it turned back to capture this 15-frame false-color mosaic on the moon. The image shows Iapetus' trailing side, which is mostly covered with the bright white ice common to outer solar system icy satellites. But the surface is stained with the dark material that covers Iapetus' leading side. The dark material fills some fissures, appears on the flanks of large basins, and even falls in linear chains in the upper left of this image. Also noteworthy are two enormous, unnamed, overlapping impact basins at the lower left.

NASA / JPL / SSI

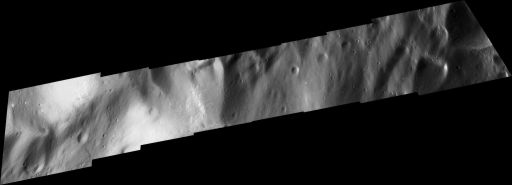

High-resolution mosaic of Iapetus' equatorial transitional zone

The 21 images for this mosaic were captured by Cassini as it receded from its close flyby of Iapetus on September 10, 2007. The mosaic covers the equatorial region on Iapetus' trailing side, including the Voyager mountains on the right. The mountains continue as a line of approximately eight peaks all the way across the image. This area is transitional between the dark terrain of Iapetus' leading side (to the right) and the bright terrain of its trailing side (to the left). In this high-resolution view, it appears that there are no "gray" areas; all areas are either bright or dark. Most crater floors are dark, while rims are brighter. This view has been cropped and reduced to 50% of its original size.

NASA / JPL / SSI

Highest-resolution images of Iapetus

This panorama cuts across the northern flank of one of the Voyager mountains along Iapetus' equator within the dark terrain on the leading side, and (when enlarged) shows features as small as 10 meters across. The most striking thing about this mosaic are tiny bright splotches, which represent small, relatively recent impact craters that punched through a very thin dark layer to bright ice below; some of the little craters have bright, icy rays. The fresh craters are so much brighter than the dark terrain that some of them required special contrast adjustment so that they would not appear saturated in this image.OK. Next, here's an image of Iapetus from the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer, or VIMS. I think it's quite notable that the stuff on Iapetus appears almost as segregated to VIMS as it does to the cameras. The news at DPS from this instrument team is the discovery of "Rayleigh scattering" in Iapetus' bright ice. This indicates, the VIMS team says, that there are extremely tiny, widely separated particles buried in Iapetus' ice on the trailing side. The Rayleigh effect is strongest where there is the least amount of pollution of the ice, near Iapetus' poles, again pointing to cleaner ice near the poles and dirtier ice near the equator.

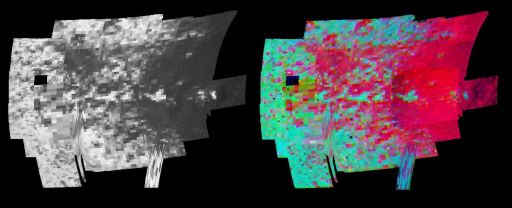

NASA / JPL / University of Arizona / USGS

Compositional segregation on Iapetus

These images of the transitional area on the west side of Iapetus' dark region, including the Voyager Mountains, were taken by Cassini's Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer as the spacecraft sped away from its September 10, 2007 encounter with Iapetus. The left image in the figure shows the amount of reflected light at an infrared wavelength of 1.75 microns, and is similar to visible-wavelength albedo images. The color image on the right shows the results of mapping for three components of Iapetus' surface: carbon dioxide that is trapped or adsorbed in the surface (red), water in the form of ice (green), and a newly-discovered effect due to trace amount of dark particles in the ice creating what scientists call Rayleigh scattering (blue). The Rayleigh scattering effect is the main reason why the Earth's sky appears blue. The Rayleigh scattering effect on Iapetus provides evidence that tiny grains, smaller than the wavelength of visible light (less than 0.5 microns) have been embedded in the surface of Iapetus. The tiny grains must be well-separated for the Rayleigh effect to become prominent, so the abundance of particles must be less than about 2 percent. The Rayleigh scattering effect shows in all areas, although weakly in dark regions (the red carbon dioxide dominates the color image), and it appears stronger away from the equator. Investigating the trend from dark to bright areas, the Rayleigh effect changes with the amount of dark material in the ice, and becomes weaker as more dark material is added. This points to cleaner ice as one moves north or south from the equator and away from the dark leading side of the moon (toward the right in the image).OK, next, here's an image from another spectrometer, CIRS, that looks at part of the electromagnetic spectrum even longer than the cameras or VIMS. Once again, I think it's quite unusual how well you can match features visible in the CIRS image to the camera (ISS) image. You can see temperature differences between crater walls and floors. Everwhere you see dark material, you see warm temperatures in CIRS, and everywhere you see bright material, you see cool temperatures.

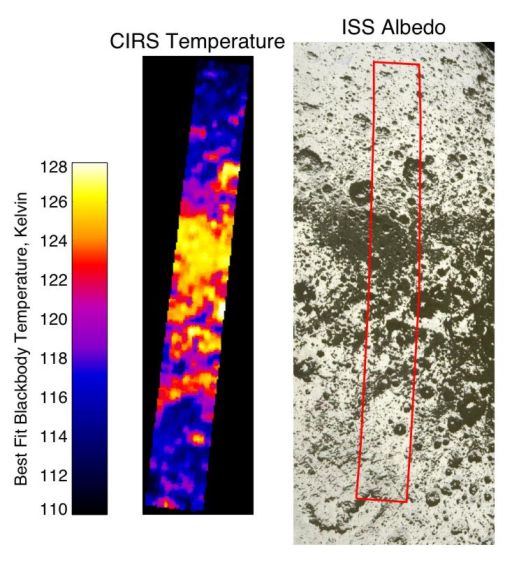

NASA / JPL / GSFC / SwRI / SSI

Warm spots on Iapetus

Cassini's Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) maps the thermal radiation emitted by cold surfaces in the Saturn system. By examining the shape of the emitted spectrum at relatively long wavelengths of 9 to 16 microns (roughly 20 times longer-wavelength than the human eye can see), the CIRS team can determine the temperature on the surface. Here, a CIRS measurement cuts across light, dark, and transitional terrains on Iapetus. The temperatures in the dark areas are, at 128 Kelvin (minus 229 degrees Fahrenheit), considerably warmer than the temperatures in the bright areas (113 Kelvin or minus 256 degrees Fahrenheit). Both temperatures are very cold, but ice is much more likely to sublimate at temperatures of 128 Kelvin than 113 Kelvin. In fact, over a period of a billion years, about 20 meters of ice is expected to sublimate at those temperatures. The cooler bright regions would only lose about 0.1 meters of ice in the same period. Ice sublimating from warmer, dark areas would re-condense to the surface all over the moon, but would be "trapped" on the cooler, brighter regions, a process called thermal segregation. This process is most likely responsible for the presently extreme segregation of bright and dark areas on Iapetus, but it doesn't explain how the dark part of Iapetus was darkened in the first place.So the Cassini team seems to be converging on agreement on an explanation for how Iapetus came to look the way it does. It's a combination of two factors: external pollution by a small amount of fine, dark particulate material being preferentially deposited on the leading hemisphere, and Iapetus' unusually slow rotation rate. Slow rotation means that its dayside gets much hotter than the daysides of others of Saturn's icy moons, which can help get the ball rolling with John Spencer's runaway thermal segregation model. And once that gets started, it's just a positive feedback cycle; ice is sublimed from the equatorial regions of the leading side, which darkens the leading side, which makes it warm even more during the long day.

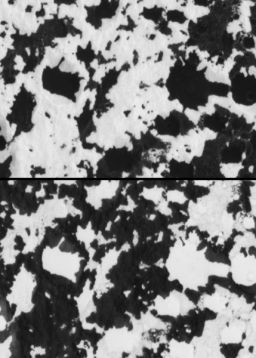

If the Cassini team is reaching consensus, though, the rest of the outer planets community is not. I talked with two different outer planets people not involved in the Cassini mission who told me they think the model is no good. And one of them mentioned something that's been a topic of broader conversation about Iapetus: is Iapetus' surface white-on-black or black-on-white? I mentioned this question to Tilmann Denk, who laughed and proposed the following experiment. Take a look at the images below. They represent the same area on Iapetus. One shows the image as it was taken by Cassini's camera; the other has been inverted -- it's a photo negative. Which one is which? Can you tell?

NASA / JPL / SSI / Emily Lakdawalla

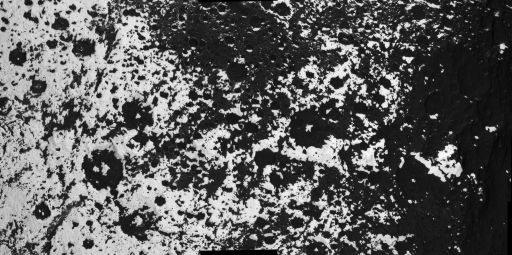

Iapetus: Black on white or white on black?

The high-resolution images of Iapetus' transitional region captured by Cassini on September 10, 2007 opened up a water-cooler debate about Iapetus: is the black stuff on the white stuff, or is the white stuff on top of the black stuff? Many people opine that despite scientists' explanations of an Iapetian iceball that has been dirtied by deposites of dark stuff, it looks very much like the white stuff is on top. Cassini imaging team member Tilmann Denk suggested this exercise: take an image of Iapetus' transitional region, where the white stuff and black stuff are intimately mixed, and invert it, making white black and vice versa. Which did you think was on top before? Which do you think is on top in the inverted image? Which is the original, and which the inverted one? (The answer to the last question is that the top image is the original, the bottom one inverted.)So now I've written too much; but there'll be much more to come, I'm sure!

For more images from this encounter, here's the page on which I collected all the raw Iapetus images...

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth