A.J.S. Rayl • Jan 07, 2014

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Mission Nears 10-Year Milestone, Oppy Roves On, We Look Back on 2013

Sols 3503–3533

Opportunity wrapped a landmark year in December sending home more evidence of ancient habitable environments at Endeavour Crater as the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission geared up to celebrate an historic milestone – the completion of 10 years of surface operations on the Red Planet.

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

Despite the aches and pains of being the longest-lived robot on another planet, Opportunity in 2013 broke the Apollo 17 rover distance record, climbed its first hill, starred in another television commercial, and made some of the most significant science discoveries on the mission, delivering findings above and beyond the original science objectives.

"We finished up Matijevic Hill, which turned out to be one of the most scientifically productive sites on the entire mission, then drove the long stretch across Botany Bay to Solander Point, and have climbed up to a pretty high point now on Murray Ridge to arrive at Cook Haven," summed up Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University.

The veteran rover will spend this Martian winter – probably through April or May 2014 – at Cook Haven looking for more clay minerals and whatever other secrets Mars may unveil.

Meanwhile, the MER 10 celebrations are about to begin. By all accounts, 10 years of surface operations on Mars is an astounding achievement and throughout January 2014, a flurry of events and happenings are scheduled to mark the milestone. Following a NASA Headquarters press conference in Washington DC, on January 3, 2014, the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum will open its doors to a MER exhibit, 10 years to the day of Spirit's spectacular bounce down into Gusev Crater.

Curated by John Grant, MER science team member and geologist in museum's Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, the exhibit involved MER team members who selected the 50 images taken by Spirit and Opportunity for the display, creating, effectively, a "team's cut" of the best of 10 years of roving Mars.

Working at Cook Haven

Opportunity pulled into an area of bright outcrops dubbed Cook Haven in December 2013, named for the legendary Captain James Cook who sailed the oceans in the mid-1700s to find new lands. The Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has detected harboring clay minerals there and the rover is hunkering down for the Martian winter to find and describe them.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell /ASU

Spirit was never as lucky as Opportunity and its location, further south of the equator than its twin, meant every winter was life threatening. After slipping into a hibernation mode in March 2010 during the last Martian winter, Spirit never "woke up." But it had worked its heart out, trundled through some of the toughest terrains on Mars, and succeeded in returning evidence of past water as well as an ancient volcaniclastic environment. Along the way, Spirit defined 'the right robot stuff' and set the standard and 'work ethic' for her twin and all future rovers to follow.

"The little rover that could," as Spirit came to be called, remains parked near Home Plate in Gusev Crater, a monument to exploration. In true twin fashion Opportunity carries on with seemingly enough determination for them both.

It seems hard to believe, but Opportunity has been roving and working on Mars ever since she blew our minds and scored the first 300-million-mile, interplanetary hole-in-one, bouncing to a landing inside Eagle Crater on January 24, 2004 Pacific Standard Time [January 25 Universal Time].

On January 23rd, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) – where all of NASA's Mars rovers have been designed and built and which serves as the rovers' mission control – will hold a press event in Oppy's honor. That night, Planetary Radio will broadcast a MER special January 23rd, featuring Bell, MER science team member John Grotzinger, now project scientist for Curiosity, MER EDL System Manager Rob Manning, now chief engineer for Curiosity, and Bill Nye, Planetary Society CEO, who designed the Mars Dial both MERs sport.

The following day, the MER science team's latest major paper, on Opportunity's findings at Matijevic Hill, will be published in Science.

The Planetary Society, meanwhile, will be celebrating online throughout January 2014, with a series of videotaped interviews with MER team members, including MER's Principal Investigator Steve Squyres and Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, and President of The Planetary Society, Jim Bell, lead scientist for the MERs' panoramic cameras (Pancams).

Spirit: A monument to planetary exploration

This artistic image shows Spirit's approximate position and location in Troy, on the west side of Home Plate where the rover is now a monument to planetary exploration. Artist Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional Spirit into a scene created by pictures taken by the rover.NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

While Earthlings celebrate the big 1-0, Opportunity, oblivious to the milestone, will rove on, into its sixth Martian winter and onto new sites in search of more past water, other ancient landscapes, and more secrets about how much Mars was once like Earth.

Scientists have long known that Endeavour dates to the Noachian Period on Mars, some 3.7 to 4 billion years ago, a time when the Red Planet is believed to have been wetter and warmer. And, because where there is water on Earth, there is life, most scientists extrapolate that Mars is a planet that could have fostered life. Opportunity began traveling back to that geologic time in August 2011 after arriving at Endeavour.

The MER team knew from data acquired in 2008 by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), that phyllosilicates, specifically smectite clay minerals were hidden in the rocks and remnant rim sections of Endeavour. That's the main reason the team chose to undertake the journey to Endeavour.

Guided by a CRISM map, produced by Arvidson, who's also a co-investigator on CRISM, the rover and the MER team ground-truthed the presence of those clay minerals in a rock unit they called Whitewater Lake at Matijevic Hill in December 2012 and found them to be nontronites. Then earlier this year, before departing Matijevic Hill, they uncovered another, more aluminous kind of smectite, known as montmorillonite building the case for an ancient Martian environment where, indeed, water flowed and life could have emerged.

Intriguingly, on the other side of the planet at Gale Crater, the newer, bigger rover, Curiosity is finding very similar rocks and clues to a water environment that featured rivers with abundant, flowing water. Study by study, the story of Mars that was written in 2013 bolsters the long-held notion that once, long, long ago, Mars looked a lot like Earth.

Certainly, both Mars and Earth are in the habitable zone of our solar system – but then so is Venus. Thus, there is much to be learned from planetary exploration and especially from what happened to our sister planet Mars. The contributions already made by Spirit and still being made by Opportunity during the mission's near-decade of surface operations are building our database in a big way and clarifying our view of Mars, as well as making space history.

As December dawned at Endeavour, Opportunity was near the top of Murray Ridge at Moreton Island. The team, again, was guided there by Arvidson's latest CRISM map in which the outcrops there "glowed" with the signature of clay minerals. "It's a really large exposure of matrix with a few, large dark clasts that we've never seen before to this areal extent," said Arvidson.

Although Moreton Island is "definitely breccia, wind eroded impact ejecta," as Squyres put it, hurled up from whatever created Endeavour Crater, the team is still working on the data to determine its chemistry and the source of the infrared signature CRISM detects.

Since Opportunity's two mineral detectors – the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) and the iron-detecting Mössbauer spectrometer are no longer functioning, the MER scientists, in a thoughtful, creative workaround, are now relying on CRISM to function as the rover's "new" mineral detector.

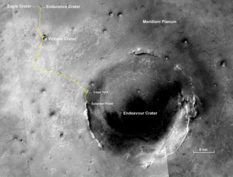

10 years and roving

The gold line on this image shows Opportunity's route from the landing site, in upper left, to the area it is investigating on the western rim of Endeavour Crater as the date approaches for the rover's 10th anniversary on Mars, in Earth years. The map shows Opportunity's location as of its Sol 3486 (Nov. 13, 2013). By that sol, it had driven 24.01 miles (38.64 kilometers) and was ascending Murray Ridge above Solander Point on the rim of Endeavour Crater. This traverse map was made by MER science team member Larry Crumpler at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, Albuquerque. Malin Space Science Systems, San Diego, built and operates the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's Context Camera, which took this image.NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

From Moreton Island, Opportunity drove south along Murray Ridge then turned east (left) and barely over the top of the ridge, onto the crater or inboard side, and into an area of very bright outcrop. A winter wonderland dubbed Cook Haven, this area glowed even brighter with the infrared signature of clay minerals in Arvidson's CRISM map, and so the rover settled in over the Christmas / New Year holidays on a north-facing slope, to soak up as much of the winter sunlight as possible while checking out chosen targets.

"Cook Haven is a gentle swale – or little valley – and we're up against the north-facing outcrop of breccia called Cape Douglas, and on a target called Cape Darby doing a set of measurements," said Arvidson.

Like Moreton Island, Cook Haven outcrops appear to be made up of more breccia, which the MER team named Shoemaker Formation, after legendary planetary scientist Gene Shoemaker. "The idea is to kind of work the different materials that are evident that we can already see," said Arvidson. "They could be all be Shoemaker or they could have some Matijevic Formation, the really ancient, pre-existing rock like the Whitewater Lake, or we could find something new. We don't know yet. It remains to be seen."

Opportunity should have time to sort it out. In the southern hemisphere of the planet, where the rover is exploring, winter solstice falls on February 14, 2014, and so with seasons on Mars being approximately twice as long as on Earth, the rover may be at Cook Haven through April, perhaps beyond. The plan now calls for the rover to spend "many weeks to maybe a few months" at Cook Haven, describing the geologic setting for the clay minerals and checking out whatever else may be around for the finding, said Squyres.

Curiosity may be claiming the headlines these days, but that's not stopping Opportunity. Neither is its arthritic shoulder, stiff front wheel, broken heater that makes it completely shut down every night, or the loss of its two mineral detectors. The veteran MER is not only roving on but conducting groundbreaking research and making some of the most tantalizing discoveries in its near-decade of roving and working on Mars. "It's been a bumper crop year," said Arvidson. "Everything we've seen since arriving at Endeavour Crater is new."

The MER team is currently mapping the north-facing slopes or 'lily pads' and finalizing Opportunity's multiple winter targets within Cook Haven. "We're figuring out where we can go," Arvidson added. "From that, we'll then scope out a strategy for the winter. A combination of science and power will determine we'll be going within this roughly 30-meter by 30-meter space."

A star of Mars and screen

Opportunity, the longest living robot on another planet, can be seen roving through a couple of the new series of General Electric commercials that aired in 2013. The series is part of the corporate giant's latest "Brilliant Machines" advertising campaign. This is a "screen grab" from one of them. Despite a little gender glitch – in the commercial Opportunity "speaks" in a distinctly male voice when, in fact, the MERs were deemed in the beginning to be of the feminine persuasion – the commercials have created a buzz for their sci-cool entertainment value and show how the MERs have become cultural icons, especially considering all the other stars in this series of commercials are fictional robots.General Electric

The best news is Opportunity will be able to rove, at least a little, from one north-facing slope to another and work throughout the Martian winter. "As I've said before, it's not how long Opportunity has lasted or how far it's driven, but how much exploration we continue to do with this rover – that's the amazing thing," said John Callas, MER project manager, at JPL.

Despite Opportunity's incredible longevity and all the amazing science the robot field geologist has returned, 2013 also brought some sad news. Astrophysicist Tom Wdowiak, an original MER Athena Science Team co-investigator, who operated the Mössbauer spectrometers for Spirit and Opportunity, passed away in April. "He was a really passionate, really enthusiastic, and a much-loved member of our team," said Squyres. "When you lose someone like Tom, it hits pretty hard."

But the mission carried on and Opportunity continues to rove, just as Wdowiak and all the team members MER has lost over the years would want.

Given what the CRISM data are showing, there is much more rich Martian history to uncover as the robot field geologist time travels through the strata in Endeavour's rim. The scientists have already spotted "a field geologist's dream," as Arvidson calls it, some 600 meters further south.

"It's a beautiful stratigraphic section of crust that's exposed on the western side of Endeavour's rim," said Arvidson. "You can walk up and down through time and along time following the outcrop."

"It's going well," reflected Squyres as December came to a close. "We've got a healthy rover and we're still going strong."

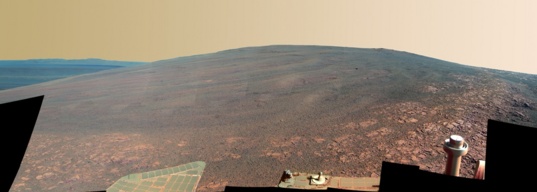

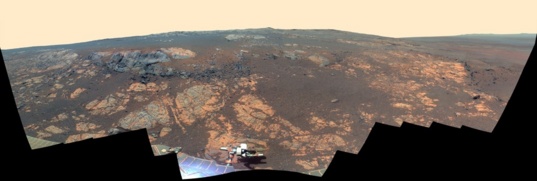

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

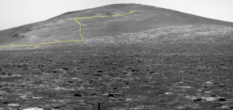

Murray Ridge

Opportunity captured this view of Murray Ridge in early October from a position at the base of Solander Point. The component images were taken over the span of five sols or Martian days, beginning on Sol 3446 (Oct. 3, 2013). The ridge, which forms the backbone of Solander Point, is named in tribute to Bruce C. Murray (1931 - 2013), a former director of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and one of the founders of The Planetary Society. Orbital observations indicate the presence of clay minerals further up this hill, more evidence of ancient flowing water and possible past habitable conditions.Opportunity from Meridiani Planum: Looking Back on 2013

When 2013 rang in on Mars, Opportunity was on Matijevic Hill in the Cape York section of Endeavour Crater's eroded rim, in the midst of returning to specific targets chosen during a "walkabout" of the hill in months previous.

Named for JPL Mars rover pioneer Jake Matijevic, one of the original members of the MER design team and former chief of MER engineering, Matijevic Hill was deemed the "sweet spot" for phyllosilicates in Cape York. CRISM had detected phyllosilicates there, specifically smectite clay minerals and using additional data from the orbital instrument Arvidson created a pixel-by-pixel map made that pinpointed the location to within 5 meters. The MER scientists had just concluded that the clay minerals it had come to Endeavour to find were in the oldest rock unit Opportunity ever found, existing before the impact that made the crater, which they dubbed Whitewater Lake.

Where water once flowed

Opportunity took this close-up picture of the tiny veins running through the Whitewater Lake outcrop with her Microscopic Imager in January 2013. The MER scientists confirmed that the veins are calcium sulfate. "It could be gypsum and it could be something else," said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres. "Our suspicion is that it's probably gypsum, but the calcium sulfate finding is solid. This is a big one."NASA / JPL-Caltech

In January, the robot field geologist found more evidence of flowing water in the form of "thin, little calcium sulfate veins that clearly show water flowing through cracks in the ground here," Squyres told the MER Update. Those little veins are in the same flat, light-toned Whitewater Lake rock unit the team concluded was harboring the smectites.

In February, Opportunity climbed further up the hill to check out the newberries, small spherules like it had found in Whitewater Lake, at Flack Lake, and then to look for the contact or boundary between the Shoemaker Formation impact breccias and the older Whitewater Lake and Copper Cliff outcrops that sit just stop the Whitewater Lake unit on Matijevic Hill. Rather than a clearly defined boundary, they found "a gradational contact," "a mixing of materials" as the crater ejecta were emplaced said Squyres. "The month was devoted mostly to trying to understand how the clay bearing stuff we see at Whitewater Lake with all the newberries in it is related to the Shoemaker-like stuff further up the hill."

Opportunity made stops at outcrops dubbed Fecunis Lake and Maley, and then drove back to Big Nickel and boxwork targets named Lihir and Esperance, which is just a couple centimeters from Lihir. On Earth, boxwork is an uncommon type of mineral structure or speleogen formed by erosion rather than accretion. On Mars, "the chemistry from our first quick look, was very, very interesting," said Squyres. So they decided to find out what "interesting" meant.

Whitewater Lake

Whitewater Lake is the large flat rock in the top half of this image, the oldest rock unit Opportunity has ever found, dating back to the time some 4 billion years ago before an impact excavated Endeavour Crater. The MER science team concluded that the Whitewater Lake unit is harboring at least some of the clay minerals it came to find at Matijevic Hill. The dark blue nubby rock to the lower left is Kirkwood, which bears nonhematite spherules Steve Squyres dubbed newberries. The rocks to the lower right look like breccias and resemble other rocks in the area hurled up and deposited by the impact that created the crater and classed by the MER team as Shoemaker Formation.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

That work continued in March as the operations team on Earth prepared for the upcoming solar conjunction and MER science team members headed to Texas for the 44th annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC), to report on the robot field geologist's findings at Endeavour Crater.

In a very short time at Matijevic Hill, Opportunity had returned evidence for clay minerals, mystery "newberries," veins, large and small, running through bedrock, and ancient soft rocks, older than any the rover had ever before found. It was a sum of discoveries that provided solid evidence of a watery, habitable environment suitable for the emergence of life as we know it – and they had done it despite the loss of its mineral detectors by enlisting CRISM, a brilliant workaround by a team renowned for its workaround capabilities. The MER presentations packed the room at the conference.

Opportunity spent most of April either preparing for solar conjunction – filing pre-programmed assignments – or in it, working away quietly on gleaning the chemical composition of Esperance with her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS). This celestial alignment occurs every 26 months or so when Mars and Earth are opposite sides of the Sun. Communication between the two planets is disrupted during this period and ops teams enter a two to three week communications blackout.

Just before the rover was to resume normal operations, it suffered an electronic "hiccup" known as a warm re-boot and went into auto mode, a kind of safe mode when something doesn't go right. "This is nothing that freaked anybody out," assured Squyres.

Actually, Opportunity had been having issues with its Flash memory system for several months prior to solar conjunction and the MER engineers were prepared. "We made sure we were resilient against that kind of thing and that the rover was resilient," informed Callas.

And she was. "Opportunity came through solar conjunction fine," said Bill Nelson, chief of rover engineering at JPL.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

Matijevic Hill Panorama

Opportunity took the hundreds of component images for this panorama with her stereo panoramic camera (Pancam) from Nov. 19, 2012 through Dec. 3, 2012. Named in honor of JPL's Jake Matijevic, one of the creators of Spirit and Opportunity and a Mars rover pioneer, the hill is an area within the Cape York segment of Endeavour's rim. Jake passed away on Aug. 20, 2012, shortly after Curiosity landed. "It's still very hard," said Ashley Stroupe, one of the rover planners, during an interview this month. "We're here exploring Matijevic Hill, so his name is in our minds every day. A day doesn't go by when we have a question and know the person who would know that answer off the top of his head was Jake. We miss him tremendously. It's a terrible loss for everybody and Mars exploration in general. He was one of the incredible people behind the whole program."With solar conjunction behind them and the clay minerals 'in the can,' so to speak, the team was getting anxious to move on. The mission's sixth Martian winter was on the horizon and the plan was for Opportunity to work out the season at Solander Point, the next major eroded remnant of Endeavour's rim to the south.

Solander Point offered a bounty of north-facing slopes, ideal for wintering because the Sun during the winter on Mars in the southern hemisphere rises and sets low in the northern sky. It was approximately 2 kilometers (about 1.4 miles) away and JPL engineers projected that if Opportunity was going to winter there, it had to be there by August.

After finishing work at Esperance and sending home more evidence of clay minerals from Matijevic Hill, Opportunity left Cape York on May 14th and embarked on the journey south along the western rim of Endeavour Crater. "I call it our winter sprint," said Scott Lever, one of the MER mission managers. And the rover that loves to rove seemed as ready as ever.

During its second drive, the veteran MER broke the Apollo 17 rover distance record of 35.744 kilometers by 16.13 meters, becoming the second farthest traveling, manmade vehicle on another planet. It also, as history had it, put Opportunity just 1.240 kilometers away from taking the "gold" in rover distance from the Russian Moon rover Lunokhod 2.

For some 40 years, Lunokhod 2, which explored the Moon's Le Monnier Crater for about five months in 1973, held the record with a well-published 37 kilometers (23 miles) distance. For Squyres however, that seemed "too round of a number." So, he began a quiet investigation, reaching out to the Russians through Phil Stooke, associate professor at University of Western Ontario, and author of The International Atlas of Lunar Exploration and The International Atlas of Mars Exploration.

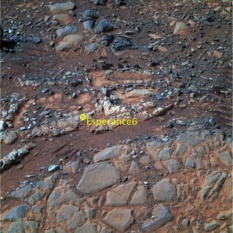

Esperance

Opportunity studied Esperance in April and May 2013, using its cameras and its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS). From the data the rover sent home, scientists were able to determine that Esperance's composition is higher in aluminum and silica and lower in calcium and iron than other rocks the rover has examined during its exploration of Meridiani Planum. The scientists eventually inferred that what they had found were signs of a more an aluminous smectite than the more iron-rich smectite it ground-truthed previously at Whitewater Lake. The more aluminous smectite clay minerals are known as montmorillonites, which usually form during intensive alteration by water. This image is presented in false color to make differences between materials easier to see.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

At the same time, Squyres asked MER science team member, geologist Brad Jolliff, of WUSTL, also a member of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) team, to check the Lunokhod 2 traverse distance using the latest images from LROC in which the tracks made by Lunokhod 2 can be seen. The tracks are "remarkably well preserved" and can be readily seen in the images," Jolliff said. "But it's not easy to see everywhere it went."

Turned out Russian planetary mapper Irina Karachevtseva and her colleagues at the Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography (MIIGAiK) had already revised Lunokhod 2's mileage, using those LROC images. The new distance, they reported, is 42.1 kilometers, basically the distance of a marathon.

That comes close but is slightly more than the WUSTL estimate of 41.8 kilometers – but the story isn't over. "Everybody agrees now that it was at least 40 kilometers," said Squyres in June. "But we're still working out exactly what the numbers are, both in the United States and in Russia." And they are working still to arrive at an official final distance for Lunokhod 2.

Meanwhile, Opportunity put her pedal to the metal during the second half of May, but leaving Cape York would take a while. "It was something like getting out of L.A., but without the traffic," said Nelson.

The rover finally cleared Cape York proper on May 23rd and pulled onto the Bench, the apron area surrounding Cape York. It then headed into Botany Bay, a tilted plains surface, from which Sutherland Point and the small circular Nobbys Head rise up, isolated remnants of Endeavour's highly eroded rim.

Actually, the rover made such impressive tracks in May – "beating the average distance that we expected to drive each sol," as Nelson reported – that the MER team decided it could afford to take a slight diversion off the "rapid transit route" to check out a small crater, and take pictures of Nobbys Head.

On the first day of June, Opportunity pulled up to Sutherland Point, the peninsula-like chunk of crater rim situated between Cape York and Solander Point. From there, the rover cruised onto Nobby's Head, just to the south, and drove around the circular hill's western flank, or far side, conducting stereo imaging of its north-facing slopes. "Based on orbital images, it's a possible bail-out for the winter, if there's some engineering emergency or something unexpected that happens," Arvidson said.

Bright deposits seen in HiRISE images from MRO indicate there may be flat, light-toned rocks at Nobby's Head that are like the ancient Whitewater Lake outcrops on Matijevic Hill, so the rover "took the scenic route," said Squyres. But there was no outcrop target within reach of her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm, and the team "decided to punt," Callas reported at the end of June. "We want to get to Solander by August 1st."

Despite her age, Opportunity was having no trouble sprinting toward Solander and June proved to be pretty much all about driving and the rover seemed to be in fine form, roving on 13 of the month's 30 sols as it continued the trek south along Endeavour's western rim. Everyone was happy to be on the road again. "It's great to be doing these long drives," said Ashley Stroupe, MER rover planner, at JPL. "We're making really good progress and we're driving past interesting stuff and getting beautiful images of different rocks and formations down every day."

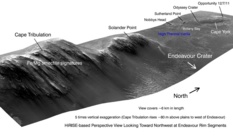

Endeavour Crater's west rim

This image shows Opportunity's stomping grounds since arriving at Endeavour Crater in August 2011. The rover began its expedition at Cape York. After spending nine months exploring Matijevic Hill, the rover departed Cape York in May 2013. Since then, it has traveled south driving by Sutherland Point and stopping briefly to check out Nobbys Head on its way to Solander Point and Murray Ridge, where it is now. This graphic was put together with an image taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO.NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

Other than another annoying Flash memory error on June 12 and some stall issues with her IDD, the rover remained in good health and seemed, as always, to be raring to go. No one on the team was terribly surprised.

With Solander Point coming into better view with almost every passing sol, the MER scientists were beginning to see more and more structure on the lower slopes, and more and more detail. "We're driving as fast as we can," said Squyres. "We can't wait to get to Solander Point."

On June 21st, 2013, Opportunity quietly chalked up its fifth Martian year and roved on. [One Mars year is 686.98 Earth days or 1.88 Earth years, roughly equivalent to two Earth years.]

In July, the robot field geologist dashed across Botany Bay between Nobby's Head and Solander Point, logging more than 215 meters in seven drives. On the way, she roved past the 10th anniversary of her launch, July 7, 2003, conducted a drive-by shooting of a small crater dubbed Charlie Brown [after the command service module of Apollo 10], "tasted" the soil at a patch of Martian dirt nicknamed Queen Adelaide – "it's basalt," said Arvidson – and paused to soak up sunlight and take images of the Martian moons' transits of the Sun with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam).

Then, the robot field geologist went on to complete most of the last leg of her trek from Cape York to Solander Point – that is to say the base of Solander was in clear view and any concerns about the rover not making it in time for its sixth Martian winter dissipated by mid-July. The August 1st arrival date, based on predictions made earlier in the year, slipped to December as a result of fair weather and level terrain. "It was smooth sailing in July," summed up Stroupe.

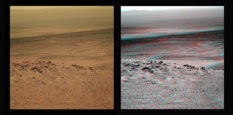

Opportunity's postcards from Nobby's Head

These images, which Opportunity took in mid-June 2013 with her Pancam while roving around the far end of Nobby's Head, were processed, colorized, and rendered into 3D by Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, author, and member of UMSF.com. They are, of course, the same image, near true Martian color on the left, and on the right in simulated 3D. You will need to don your red-blue glasses in order to get the full effect of the 3D image on the right. Also, check out Atkinson's blog, The Road to Endeavour, at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Nicely ahead of schedule, the team decided it had the time and Opportunity had the energy to divert from its "rapid transit route" into kind of "suburb" of Solander, an area that appears darker in images taken from orbit by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard MRO. So during the last week of July, the rover drove into the dark suburb and found some of the weirdest Martian rocks the scientists have seen yet, coarse-grained, upturned dark boulders that look like mud to some and like nothing the MER scientists had seen in more than nine years of exploring Meridiani Planum.

"They are another interesting set of rocks that feature an abundance of rounded, sand-sized particles embedded in a matrix and cement," said Arvidson, "They're different than anything we've seen before, except perhaps for some coarse-grained rocks in Endurance Crater."

The robot field geologist took some Pancam pictures of one large dark boulder dubbed Rusty Crevice, then snapped images of another called Black Shoulder, which it studied up close.

A sandy conglomerate that is "an amalgamation of rounded particles that may be a millimeter or less across," as Arvidson described it, Black Shoulder is something that's very unusual by the MER scientists' reckonings. And it's where the rover spent several of the last sols or Martian days of the month digging in to get a better look before it had to rove on to Solander's base.

During the first days of August, Opportunity made actual "landfall" in the Bench or apron area surrounding Solander Point, driving up along the inboard or eastern side of about 90 meters to the south of the northern tip. Where Cape York exposes a few meters of vertical cross-section through geological layering, Solander Point exposes "about 10 times as much," according to Arvidson. Like rings inside trees, every layer marks a different time and tells a different story. The science team is "kind of like in Disneyland," Callas said that month.

There was a lot to see and do. As Opportunity drove up to the base of the Solander Point, it crossed over a geological boundary between ancient eras, documented the boundary area in images and checked out as many attractions as possible August, even venturing up slope into a boulder field to compare rocks and layers there to those the rover found at Cape York.

One boulder, Red Poker, was readily familiar, of the layer most traveled by Opportunity, cross-bedded, mainly Aeolian sandstones that the MER team labeled Burns Formation. Another boulder, Tick Bush, proved to be basalt, also typical of what the rover has seen around Meridiani Planum.

While navigating the boulder field in mid-August, Opportunity came frighteningly close to running into a boulder called Mulla Mulla. "It was a near miss," said Nelson. But the rover scooted unscathed and moved on to a flat, light-toned rock dubbed Platypus, which turned out to be part of the older Grasberg rock unit that the rover first discovered on the Bench at the northern end of Cape York back in July 2012 in a rock called Grasberg.

From Platypus, Opportunity headed north toward the northern tip of Solander Point. By month's end, the rover was staring at what looked to be another scientific gemstone on the Red Planet – a small cliff or escarpment that runs for some 80 meters along on the eastern side of Solander Point toward the northern tip. "It's really spectacular," said Arvidson. "It's about 40 centimeters (1.3 feet) high, and has boulders in it and a cap rock on top of it. We've never seen anything like this."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

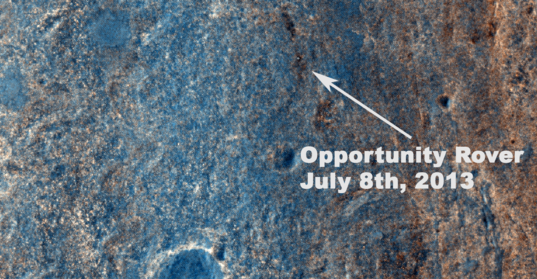

Opportunity 10 years after launch

This image taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) captures Opportunity as she was roving south (at the end of the white arrow) to new science targets and the place where she will spend her sixth Martian winter, Solander Point, another portion of the dissected Endeavour rim. The relatively level ground between Cape York and Solander Point is called Botany Bay. The image was taken 10 years after Opportunity was launched from Florida on July 7, 2003, EDT and PDT (July 8, Universal Time).Opportunity spent the beginning of September and Labor Day weekend at the escarpment. Then, as the month progressed, the rover rounded the northern tip of Solander Point and drove into her winter campgound, taking in the view of the new landscape on the western or outboard side of this section of Endeavour's eroded rim.

The rover must endure constant, sometimes radical fluctuations in daily temperatures, not to mention survive temperatures dipping to 100 degrees and more below freezing, all of which is really tough on her metal parts. Of course, the veteran rover has proved her resilience many times over while exploring this sub-freezing planet and the MER ops team is as experienced as they come – plus Mars, as they like to say, is "cooperating." Even so, this will be Opportunity's sixth Martian winter.

Scarpin' it

During the first part of September 2013, Opportunity was investigating rock outcrops along an escarpment – or scarp as geologists call it – on the eastern side of Solander Point. This scarp is a boundary or contact between the Bench, which surrounds the eroded crater rim section, and the rim. The pictures that went into this image were processed in near true color by Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, planetary outreach godsend, and blogger of many celestial things. For more of his work on MER, see: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/NASA / JPL-Caltech, Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

The plentiful assortment of north facing slopes on this side of Solander brought good tidings. Ranging from 5-degrees to 20-degrees, the slopes offer havens where the rover can position its solar arrays directly toward the Sun in the northern sky and continue to produce enough energy to keep driving and working through winter. Despite her age and dusty solar panels, "the prognosis for winter is good," said Lever.

As September turned to October, Opportunity was at the base of the northwestern flank of Solander Point, sitting on the contact between it and the Bench, snapping the hundreds of pictures it takes to produce a color panorama of her sixth winter campsite. Then, she motored on, looking for "juicy" slopes, as Lever described them, close to interesting science targets, like the outcrops where Arvidson's CRISM map indicates clay minerals from eons long ago await discovery.

After finishing its imaging assignment, Opportunity headed up onto the ridge and drove back to the past, crossing onto ancient terrain, stopping at an outcrop dubbed Kangaroo Paw. "We've never climbed a hill like this with Opportunity," added Squyres. "We've climbed out of craters before, but this is the first mountaineering we've ever done with this rover."

From Kangaroo Paw, Opportunity moved on to another slope and another outcrop and then another, winding its way across and down the ridge. "We're exploring the outcrops on the western flank of the ridge, heading south/southeast from the northern tip," Arvidson said. So far, all the outcrops look like breccias, likely hurled up from whatever impact caused the formation of the crater all those billions of years ago.

The robot field geologist was following the ridge to the team's hoped-for winter destination, an area of bright outcrops about 200 meters to the south of its position at the base of Solander Point where it shot the new mission panorama, an area where CRISM detected clay minerals.

As the Martian winter began to set in, Opportunity suffered a loss of energy, but the loss was within expectations. "Winter is coming," said Squyres. "Opportunity is doing great.

The MER ops team instituted the 'lily pad' strategy, directing the rover move from one north-facing slope to another, so it can rest while angling its solar arrays directly to the Sun and stay power safe. "We've been able to find good lily pads near interesting stuff, and it's going as we had hoped," said Stroupe in October.

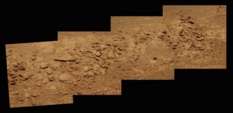

Opportunity's ascent up Murray Ridge

"This graphic that Larry Crumpler put together is awesome," said Steve Squyres, MER PI, in November 2013. "It's a Pancam shot that was back when Opportunity was crossing Botany Bay looking toward Solander Point / Murray Ridge, and Larry plotted our route up hill. It shows how much climbing we've done and it's pretty dang impressive." Opportunity took this image with its Pancam on Sol 3365 on approach to Solander Point and Crumpler plotted the rover's path up Murray Ridge, in yellow. Crumpler is the Research Curator of Volcanology and Space Sciences at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, and associate professor at the University of New Mexico, who contributes his blogs to The Planetary Society's website. See: http://www.planetary.org/connect/our-experts/profiles/larry-crumpler.htmlNASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / L. Crumpler

"We're seeing familiar sorts of geology, like what we saw over at Cape York, though there are clues that as we work our way higher and higher and to the south, we'll start to get into different things," added Squyres.

Although Opportunity really began to feel the sting of winter in November, she pressed on, pausing to check out a pristine path of dust, named Yellow Bellied Glider, only the third dust patch measurement the rover has taken on the whole mission and one that may be, according to Squyres, "the best yet."

Meanwhile on Earth, the ridge – which forms the backbone of the Solander Point section of Endeavour Crater's eroded rim – was officially christened Murray Ridge, for Bruce C. Murray, who founded The Planetary Society with Carl Sagan and Louis Friedman in 1980 and served as director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) from 1976 to 1982.

The christening was announced November 10th at a standing-room-only memorial for Murray, held at the California Institute of Technology's Athenaeum, and Solander Point came to reference only the tip of Murray Ridge.

One of the first generation of explorers to robotically depart Earth for other planets, Murray blazed trails, especially in imaging, and then went on to guide the troops at JPL. "He led JPL during a time when the planetary exploration budget was under pressure and the future for planetary missions was not clear. His leadership brought us through that period with a strong exploration program," Squyres said. And JPL, of course, is where Spirit and Opportunity were designed and built and care for. Murray passed away in August at the age of 81.

Opportunity spent the second week of November into the third leaving Yellow Bellied Glider and hiking to Moreton Island, where CRISM data showed a "big glowing signature for clay minerals," said Arvidson. If it seemed to MER followers that it was taking a long time, it wasn't because the team wasn't moving. "We were boogying the whole time, but boogying slowly. It's wintertime," Squyres said.

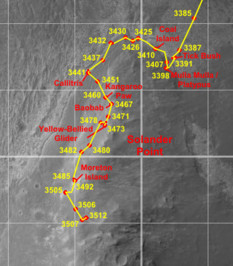

Opportunity Route Map

This route map, produced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UnmannedSpaceFlight.com, shows Opportunity's travel through its Sol 3512 (Dec. 10, 2013), and its approximate location. It tracks the rover's route around Solander Point, into its winter campgrounds on the western side of this section of Endeavour Crater's eroded rim, and up and south along Murray Ridge. Tesheiner creates his route maps, which are regularly featured in the MER Update, from images taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and then charts the rover's drives, in yellow, and labels the main waypoints and stops along the way (in red).NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / E. Tesheiner

The CRISM data indicates the presence of clay minerals Moreton Island, "but not nontronite, the iron-rich member of the smectite group of clay minerals, but an aluminous clay that could be montmorillonite, like we found at Esperance on Matijevic Hill," clarified Arvidson. "They are all in the same family of clays, but have different compositions. Montmorillonite tends to be formed when the rocks are a little but more leeched by water."

Moreton Island features "a whole lot more soft, really bright matrix exposed than anywhere else I've seen in terms of this areal extent," said Arvidson, who's been studying the geology of Mars since Viking. The matrix, "the really fine stuff," he speculated, could be what is carrying the clay mineral signature.

But the outcrop also has "some very strong, erosionally resistant rock clasts that are embedded in the fine-grained, more erodible matrix," noted Squyres. "There's been a lot of wind erosion, and because of a prevailing wind direction, the sand blasting that takes place as the wind blows sand across this outcrop has created a kind of grooved or striated appearance to this thing."

Opportunity studied the outcrop as best she could. "It was too rough to brush or grind into, so our measurements have a little bit of dust on the surface," said Arvidson. In the analysis, the Moreton Island outcrops "look like Shoemaker Formation breccias, but not quite," he added. "We're still trying to figure out the chemistry. That will be done as a set of Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) abstracts to be submitted [the first week in January 2014]."

Endeavour, however, is a big crater – 22 kilometers across. "We're not going to find a uniform set of breccia deposits," Arvidson pointed out. "From the huge amount of matrix, the very fine-grained material into which the clasts are embedded, we think these breccias may have been altered from glass to clay. But all these alterations are, for the most part, pretty modest. You can have the same elemental abundances and all you're doing is turning glass into clay, but we wouldn't be able to tell that from the APXS, because all we get [from that instrument] is elemental abundance. Without the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Min-TES) or the Mössbauer spectrometer, we are relying on CRISM as our mineral detector."

If this thinking bears out, "then it indicates the very fine-grained, glassy materials were altered, after the impact materials came down, in the presence of water," said Arvidson. That would not be at all surprising. "There have been lots of models of that show there would be hydrothermal circulation set up with ground ice after an impact on Mars. We're just trying to sort everything out at this point and also see if we can find more of these materials this winter."

Even though this is Opportunity's sixth Martian winter, it may be the most productive and rewarding winter it's ever had, given the exposure of bright rocks and outcrops at Cook Haven. "Where we are now – the target Cape Darby, which is on Cape Douglas – the area, is an impact breccia, because you can see the clasts and the matrix and it looks more like Shoemaker Formation than anything else," said Arvidson. "What we're trying to do now is figure out what exactly they are and how they fit into the overall stratigraphy of the rim of Endeavour Crater. Are they all breccias? If so, what types of breccias and how do they fit into the impact event. Or are we actually going beneath the breccias in this place to get the pre-existing rocks?"

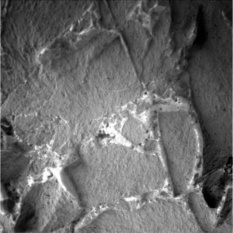

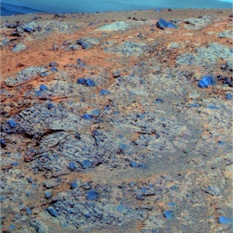

Large clasts of Moreton Island

The Pancam team produces false color images to better show the different materials and rocks in the pictures and the distinctive large, dark rock clasts embedded in the Moreton Island outcrop really pop in this one. Moreton Island is where CRISM indicated there were clay minerals, but it is yet to be determined if that evidence will be found in the lighter matrix or in the dark rock clasts. Stay tuned in 2014.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

"We're just getting started," added Squyres. "We've gotten a few microscopic imager pictures down. We're going to be at Cook Haven probably for many weeks to maybe a few months." In all likelihood, it's where Opportunity will be through the depths of winter.

Now that the rover is employing the lily pad strategy on Murray Ridge, "this winter for Opportunity will probably be like Spirit's first winter at Husband Hill," Stroupe said. That means, barring any unforeseen untoward event, the rover will continue to rove, lily pad to lily pad, and work throughout the harsh season.

"It's frustrating right now because the rock we're on is basically an impact breccia, and we can see rocks that are lower down topographically that might be Matijevic Formation or Copper Cliff, stuff that's breccia but sitting right on top of Matijevic, or it might be something new," said Arvidson. "But we cannot get there right now, because it's winter."

With Opportunity roving and working through the Martian winter, there is little time for celebration or reflection, but everyone agrees 2013 has been a stellar year for science. "It began with Opportunity measuring the Whitewater Lake area, now part of the Matijevic Formation, very unusual rocks that probably pre-exist the impact event and were just uplifted on the rim rocks," reviewed Arvidson. "Then, the veneers on the rocks, which might be carrying the nontronite. We then grinded into this fracture at Esperance and found aluminous clay – so this is all brand new – older rocks and formation of clays in a more neutral pH environment. We hadn't seen anything like any of this prior to 2012," said Arvidson.

Whatever Opportunity finds at Cook Haven, the rim sections of Endeavour promise exciting scientific possibilities. "The really neat thing is there is a huge exposure of outcrop that’s 600 meters to the south that has a glowing CRISM signature indicating aluminous clay minerals," said Arvidson. "We're looking back in older geologic time now with different water chemistry and there's a whole lot more to see along the western side of Murray Ridge going down to Cape Tribulation based on the CRISM observations – and we know where to go to find the choicest rocks."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth