A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 31, 2010

Mars Exploration Rover Update: Spirit Silent Still, Opportunity Savors Santa Maria, We Flashback on 2010

The Mars Exploration Rovers are wrapping up another year of exploring – their seventh -- having experienced both the best of times and the worst of times: Spirit continued a 10-month struggle to endure its coldest, harshest Martian winter yet; Opportunity set a new record for driving despite an arthritic front wheel and a broken shoulder, putting more miles on her rocker bogie in 2010 than in any other single year.

Even as politicians gridlocked Earth and embarrassing truths leaked out, the reality show of the decade was still playing out on Mars, and in the midst of 2010 programming schedule the twin robot field geologists surpassed the Viking 1 Lander to become the longest-lived Earth robots to work on the Red Planet.

It's worth remembering that way back when, in 2004 when the MERs set off across their respective landscapes, no one really expected either rover to survive its first Martian winter. Still, Spirit and Opportunity are seniors now, and surviving this the harshest of seasons so far is the challenge of challenges for Spirit.

Winter gripped the southern hemisphere of Mars for most of 2010. It was the fourth Martian winter for the rovers and the most life threatening for Spirit, which is further south of the planet's equator than Opportunity, and in a colder, more rugged environment. Although Spirit presumably went into hibernation, there is no way of knowing until she wakes up, which the team hopes will happen soon.

In Mars years past, Spirit had been able to position itself on a slope during the brutal winters to angle its solar arrays to the north and toward the Sun. But this year the rover was unable to get to a north-facing slope, because it was mired in a sand trap that had snared it in May 2009. While the rover had finally begun making progress on getting out, inching more than a foot closer to freedom in February of this year, the cold forced it to stop everything and shelter in place.

Hope still floats

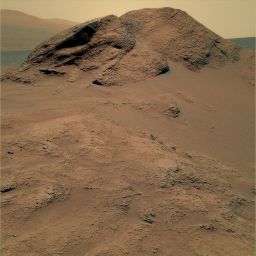

Hope still floatsThis image, which Spirit took with its Pancam in February of this year features a discreet sign of luck. Enlarge the image, then look inside the circular depression. As MER poet and aficionado Stuart Atkinson,who discovered this, put it: "That has to be a lucky horseshoe in that hole." Actually the rover created the circular depression with its rock abrasion tool (RAT); nevertheless, the horseshoe certainly wasn't planned.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / colorization by S. Atkinson

As the temperatures dropped at Gusev Crater and the rover's energy diminished, Spirit presumably tripped the low-power fault, shut down all systems but the automatic survival heaters and its mission clock, and went offline sometime in late March. That, anyway, is what it was programmed to do. The rover had held on longer than the team anticipated. Its last communiqué was received on March 22nd.

NASA engineers and scientists didn't really expect to hear anything from Spirit until around now, but since neither of the rovers has gone into hibernation before no one could say anything for certain. By April, NASA personnel had already begun listening for the rover's 'beep' through the Deep Space Network (DSN) and the Mars Odyssey orbiter. This series of tones would indicate Spirit had taken in enough sunlight fuel to re-charge its solar batteries.

As the months of 2010 progressed, models began to indicate the rover might have also tripped the mission clock fault. That would leave it in a state of not knowing what time it was, and waiting to hear from its crew. So, in July, the team also initiated a campaign of reaching out to the rover. They have been listening and reaching out to Spirit ever since.

Although December only brought more of the same static silence on Spirit's frequencies, team members held on cautiously to optimism. "We continue to listen and we continue to wait," reported John Callas, MER project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were 'born' and are being managed.

“I remain optimistic that we will hear something," said Steve Squyres, principal investigator for rover science, of Cornell University. "But it has been a long time.” There is still no reason, the engineers and scientists alike contend, to believe that this rover did anything other than what it was supposed to do, The more pertinent question, as usual, is – what has Mars done?

Despite the unknown and its attending fear, the MER team is there, ready, willing and able to do anything for its composite and titanium colleague, and generally team members remain confidant. "I have always had one rule: never bet against the rovers,” said Scott Maxwell, Mars rover drive team lead. "I'm not going to break that rule now." Neither it appears is anyone else.

"We have not given up on Spirit," underscored JPL's Bill Nelson, chief of rover engineering team. "That I can say emphatically."

However ironically, while Spirit slept in most of the year, it did manage to grab the spotlight in 2010 with what has turned out to be "the biggest science news of the year," as Squyres put it during an interview earlier this week.

A team of scientists led by NASA's Dick Morris discovered magnesium iron carbonate in data from a rock that the rover had taken back in December 2005, at the foot of Husband Hill. The discovery was not only a sign of past water, the rovers' key science objective, but it was near neutral water, more like the "fresh" water on Earth, water more conducive for the origin of life than any other pools or trickles of past water either rover had found. Planetary scientists had been looking to find carbonates on Mars for decades. Spirit sent home 'the gold.'

Over at Meridiani Planum, on the other side of Mars, Opportunity pretty much raced through the year. The rover seemed to shine all the way, as it continued on the years-long journey toward the next big attraction, a 22-kilometer diameter hole in the ground dubbed Endeavour Crater.

Despite aches and pains that have come as a result of aging, Opportunity cruised as if there was no tomorrow, pushing the envelope backwards most of the way. “This year has been mostly about covering ground. We set for ourselves the goal of reaching Endeavour Crater, and we're getting there,” said Squyres.

Even though Opportunity had to rove backwards because of a troublesome right front "hot" wheel, and had to leave her arm partially unstowed so that she looks as if she were fishing because of a broken shoulder joint, a configuration the rover was never designed to drive in, she wracked up a total of 7.578.08 kilometers (4.709 mi), more kilometers (miles) than in any other single Earth year. The rover bested her own record, of 5.310.23 kilometers (3.299 miles) set last year. And next year – get this – may be even better.

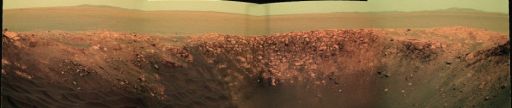

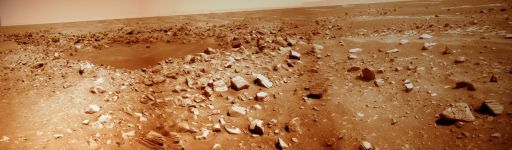

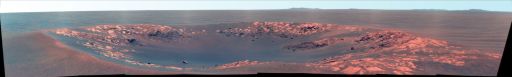

Santa Maria in glorious color

Santa Maria in glorious colorThis panorama of Santa Maria shows the fresh, young crater in glorious Martian color. The hills or rim of Endeavour Crater can be seen in the distance. They are actually about 6.5 kilometers away. This mosaic was produced by Stuart Atkinson, a member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, widely known as the MER poet..

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University / S. Atkinson

The first rover to rove 25, then 26 kilometers, Opportunity took in the sights as it drove down the plains of Meridiani, crater-hopping all along the way. Forever competitive with her twin, this rover also bucked to make some science history in 2010.

When an instrument onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter detected smectite, a phyllosilicate that hints of ancient, alkaline water, along a ridgeline of Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was directed to head for that part of the rim. Such guidance or direction, this coordination between ground and orbit at Mars, has never happened before. "This is the first time mineral detections from orbit are being used in tactical decisions about where to drive on Mars," confirmed Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St Louis.

Earlier this month, Opportunity pulled up to the last major geologic form on the way to Endeavour, a much smaller football-field-size crater dubbed Santa Maria. Extremely young geologically speaking, this crater is fresh, perhaps the "cleanest" sizable crater the rover will see on the mission.

“Santa Maria is gorgeous,” said Squyres. “It's just one of the most spectacular things that we've seen with this rover, and the panoramas we're working on are going to be some of the real signature images of this entire mission.”

"It's as great as I thought it would be," Arvidson agreed. "We can see multiple types of rocks in the wall and we're all anxious to get southeast so we can figure out what we're seeing in the CRISM data.”

The Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) – which is onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), and on which Arvidson serves as a co-investigator – detected the signature for a large patch of hydrated minerals along part of Santa Maria's southeast rim, something not seen before along Opportunity's path.

Plans call for Opportunity stay at Santa Maria through the coming solar conjunction, a two-week period where the Sun is between Earth and Mars and communications between the two planets is difficult to impossible. It begins in mid-to-late January 2011 and extends into early February, so the rovers will in effect "stand down," with Opportunity likely taking long overnight measurements of target compositions. “We're going to spend solar conjunction at a good spot on the rim,” said Squyres.

After solar conjunction, Opportunity will head on to Endeavour. “The most important thing between Santa Maria and Endeavour that we know about is – getting to Endeavour," said Squyres. "We're going to put the pedal down and go like hell."

No UFO base here

No UFO base hereAs amazing as the mission is, it still isn't enough for some people. You Tube and other Internet sites lit up in recent weeks with buzz that Spirit had discovered a UFO base on Mars. "Cool," joked Deputy Principal Investigator Arvidson. If only it were true. The rumourperps cite this image that Spirit took on its Sol 2169 with its rear hazard avoidance camera. "You are seeing reflections of the bottom of the solar panels and the rear wheels," said Bill Nelson, chief of the rover engineering team. "It happens often with the right lighting conditions," said Arvidson.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The rovers could have never gone this far without their dedicated team on Earth and in 2010 the rovers' handlers were honored with the International Space Ops Award for Outstanding Achievement by the International Committee on Technical Interchange for Space Mission Operations, also known as the SpaceOps Organization.

As the MER mission heads into 2011 and another year of exploring Mars, the way ahead looks beautifully benign for Opportunity, and positive thinking and warm wishes from around the world surround Spirit.

"They're not emissaries of just NASA or even of the United States, they are emissaries of the planet Earth," said Squyres one night nearly seven years ago after Spirit and Opportunity had safely landed. And since then, the twin robot field geologists have been taking all of humanity, if only vicariously, to Mars.

Around the world down here, everywhere – from Leicester and Kendal and London, England to Buenos Aires, Argentina to Madrid, Spain and Marseille, France, to the hinterlands of the Shandong Province in China, from Manhattan, New York to Pasadena, California, to Houston, Texas, and Vancouver, Canada – people have joined the expedition, cheering them on every rove of the way.

At some point after Opportunity landed on January 24, 2004, maybe it was in a press conference or maybe it was in casual conversation, probably both, JPL Director Charles Elachi marveled, as he has no doubt many times since: "When you go outside tonight, look at Mars," he encouraged. "And think about it. We have two rovers there."

Indeed. We do.

Spirit from Gusev Crater

Survival was the operative word for Spirit in 2010. As the year began, the rover was following commands from her crew on Earth trying to free herself.

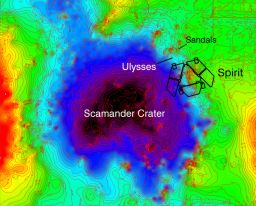

Back in May 2009, Spirit had became embedded by the sandy soils of Ulysses in an area called Troy. She had been driving south along the western edge of the old circular volcanic plateau called Home Plate to get to her next destinations, when, without warning, the wheels on her left side broke through a crusty surface layer and sunk into soft sand hidden underneath.

Spirit at Troy

Spirit at TroySpirit looks a little like a golf-cart here on the shoulder of Home Plate, the circular plateau in the center of the image. In this artist's rendition, the rover's position, mired in the sands of Ulysses at Troy, on the western side of Home Plate, is fairly accurate. The panorama is real and was taken by the rover on her Sol 743 in 2005, as she descended from Husband Hill toward Home Plate. Enlarge and look closely, the rover is in the valley to its right.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Glen Nagle

Turns out, the rover was on the edge of a shallow sand-filled crater. Seven months later, a wheel on her right side stopped working, complicating her exit. It was the second wheel to go. She had lost the use of her right front wheel back in 2005, and while that wheel uncannily started to roll again as Spirit was trying to maneuver her way out of the sandpit, it didn't roll for long and the rover was for all intents and purposes was left with with only four dependable wheels.

On January 26, 2010, NASA announced that Spirit was being re-designated a “stationary research platform,” because her efforts to extricate herself had been unsuccessful. Likening the rover’s predicament to “a golfer’s worst nightmare,” a NASA official from Washington told reporters that Spirit’s current location is probably “its final resting place.”

It set off a flurry of misreports and rumors to which Steve Squyres, principal investigator for rover science, responded: The rumors of Spirit’s death are “greatly exaggerated,” adapting the famous quote of Mark Twain.

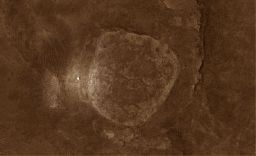

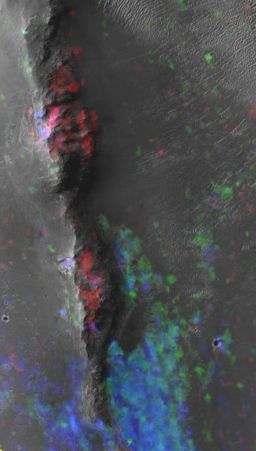

Spirit still sleeping at Troy?

Spirit still sleeping at Troy?In this picture of Home Plate, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, you can easily see the stark white figure that is Spirit to the left (west) of the geologic formation in this image enhanced by Stuart Atkinson. "It's just a screengrab from the excellent HiRISE IAS Viewer," he said. "I added some colour, then highlighted the position of Spirit. If you look carefully you can actually see bright trailing leading to Spirit - this is the result of the (right front) broken wheel being dragged through the dirt, unearthing brighter material beneath." See Atkinson's Road to Endeavour at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by S. Atkinson

Spirit, in true MER form, roved on. Even as she was being reassigned to “stationary research platform" status, she was driving, backwards instead of forward as she had been, and she was making progress. But as February wore on, the winter cold took hold and the rover, unable to effectively maneuver into a position to slant her solar panels toward the Sun as she had for the last three Martian winters, had no choice but to hunker down to wait out the long, intensely cold winter right where she was.

From atmospheric and weather models of Gusev Crater, the team knew this was going to be Spirit's toughest challenge to date. The expectation was that she would lose energy to the point of tripping a low-power fault, which would shut down all systems but her survival heaters and her mission clock, and essentially take a nice long nap.

As the outside temperatures began to fall toward -100 Celsius (-148 Fahrenheit), Spirit’s power levels dropped as anticipated to some of the lowest levels recorded on the mission. With all non-essentials turned off, the temperature inside the rover electronics module (REM) – the center of the robot, which houses the warm electronics box (WEB) that encases the computer or "brains," as well as other crucial electronics that control movement and instrument deployment – also dropped to a record low of -41.5 Celsius (-42.7 Fahrenheit). Sound beyond survivability. "But it could be worse," noted Callas.

Remarkably, Spirit held on into March, communicating once a week for three weeks. But when the rover failed to report in on its Sol 2218 (March 30, 2010) as commanded, the immediate assumption was that the rover had tripped the low-power fault and gone into hibernation. “We were all pretty surprised that the rover kept talking to us for as long as it did," said Squyres. But, at the same time, he noted, "these rovers have always over-performed."

Although team members did not expect to hear from her for months, NASA personnel began listening within days through both the Deep Space Network (DSN) and the Mars Odyssey orbiter, quickly settling into a routine in April and May. They were listening for the rover's autonomous recovery 'beeps,' which she is programmed to send once she has enough power to recharge her batteries, and emerge from hibernation. They were greeted only by the sounds of staticky silence.

Ulysses in Troy

Ulysses in TroySpirit accidentally slipped through a patch of ground in an area the team calls Troy back in April. Inside the area, the rover churned up a mixture of light-toned soils unlike anything either rover has seen. The variations in this mixture, now called Ulysses, are revealed in pastel hues visible in this panoramic camera (Pancam)image, which has been stretched to emphasize the differences. The rover used its Pancam on its Sol 1892(Apr. 29, 2009) to take the three images combined into this composite image. The three images were taken through filters centered at wavelengths of 750 nanometers, 530 nanometers and 430 nanometers. Spirit became embedded here about a week later. The two rocks near the upper right corner of this view are each about 10 centimeters (4 inches) long and 2 to 3 centimeters (1 inch) wide.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

On April 28, Spirit, surpassed Viking Lander 1's record of 6 years and 116 days to become the longest-lived robot on Mars, but the rover, as expected, slept right though it and into May. [Opportunity would cross the longevity milestone three weeks later.]

Down on Earth, MER scientists were bolstering the leading hypothesis that Spirit had found evidence of past water right in the science-rich spot west of Home Plate where she was stuck. There, in stratified soil layers with different compositions, the scientists saw evidence of what they theorize was ancient snow melt that trickled into the subsurface at her site west of Home Plate fairly recently and on a continuing basis. The seepage could have happened during cyclical climate changes in periods when Mars tilted farther on its axis, Arvidson noted, and "the water may have moved down into the sand, carrying soluble minerals deeper than less soluble ones."

The relatively insoluble minerals near the surface include, they think, hematite, silica and gypsum. Ferric sulfates, which are more soluble, appear to have been dissolved and carried down by water, since none of these minerals are exposed on the sand and dust covered surface. "The lack of exposures at the surface indicates the preferential dissolution of ferric sulfates must be a relatively recent and ongoing process since wind has been systematically stripping soil and altering landscapes in the region Spirit has been examining," Arvidson explained.

As the Martian Winter Solstice came and went on May 12 (May 13 Universal time), Spirit continued to 'sleep in' into June. But when a group of MER scientists led by NASA's Dick Morris, announced a strange looking outcrop dubbed Comanche that Spirit examined years ago is harboring carbonates, asleep or not, she roved back into the spotlight.

Spirit had come across Comanche in December 2005, while hiking down from Husband Hill and into the Inner Basin, where Home Plate had captured the rover's eyes and the team's attention. Morris, manager of the Spectroscopy and Magnetics Laboratory down on Earth at NASA's Johnson Space Center (JSC), knew from his first look at data from the Mössbauer spectrometer, which detects iron-bearing minerals, that something was different about Comanche. So long after the rover moved on, Morris kept at it, though he had to cajole some of the other scientists to help him conduct analyses.

Comanche in false color

Comanche in false colorIn this image, Comanche is the dark reddish mound above the center of the view. The image is presented in false color, which makes some differences between materials easier to see. It combines three separate exposures taken through filters admitting wavelengths of 750 nanometers, 530 nanometers and 430 nanometers. The main Comanche outcrop is about 5 meters (16 feet) left to right from this perspective. The lighter material visible at bottom right is part of another outcrop, Algonquin.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

It took a lot more testing than Morris had imagined, but the hunch and all the extra work paid off big time. Comanche is harboring magnesium iron carbonate – and a lot of it. The finding is, Squyres said earlier this week, the "biggest science finding of the year."

Carbonates on Mars have been a big deal among planetary scientists since the 1970s. These minerals typically precipitate from water and dissolve easily in acid; therefore, rocks on the surface of Mars with high amounts of carbonate would probably not have been exposed to much acid, but rather evolved in water conditions with a more alkaline pH welcoming, even nourishing of life. This discovery gives rise to the possibility of a past environment in this location on Mars that may have been more favorable to life than any other site found to date by either of the rovers. The team’s report was published in Science online June 3, 2010, and subsequently was reported on here, in an MER Special Update.

Winter lingered well into July in the southern hemisphere of the Red Planet. Newly developed models of Gusev Crater were indicating that it might have gotten so cold where Spirit was that the rover might have tripped the mission clock fault in addition to the low-power fault. That would mean the rover doesn't know what time it is. It also would mean the rover would be following a different set of commands for recovery. Rather than phoning home, it would be waiting for its team on Earth to call it.

The MER operations team and NASA specialists began doing just that with a procedure they call ‘sweep-and-beep.' “If the rover has experienced a mission clock fault, this is a necessary step," said Callas. "We wouldn’t get an active transmission from the rover in that case, so we‘re sending something to the rover to get it to respond, to wake up.” The only hitch: the rover would be listening only during a narrow 20-minute period every hour it’s awake and if it doesn't know what time it is, there is no way of really knowing when it might be listening.

Spirit remained silent through August and September, and communications engineers continued to listen but the rover wasn't talking, or they couldn't hear it. Orbital imagery and weather reports from the Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS) scientists manning the CTX camera onboard MRO informed the team that a dust storm blew right over Spirit in October. However, since the rover is incommunicado, and systems are shut down, no one knows the impact that storm had on the robot or at the location. The winds of the storm may have helped blow off some of the accumulated dust on the Spirit’s solar arrays, or it may have deposited more dust onto them. “We’ll just have to wait and see,” said Arvidson.

Topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy

Topographic map of Spirit's location at TroyThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed based upon Spirit's camera images of the location, taken before it got mired at Troy. The topographic model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State University

As much is known, so much remains unknown. “We're hampered by our lack of knowledge. We have orbital and historical data and we can make some educated guesses, but we have no ground-truth because we haven't heard from Spirit,” Maxwell reminded. “That makes it harder for us to tell – when are we going to hear from Spirit," he said.

"We're depending to some extent on just luck to hear from her again,” Maxwell continued. "Imagine throwing darts at a dartboard for a bull's eye, only the target is on a truck that's bouncing down the road and you're throwing wildly hoping to hit it -- that's about the situation we're in trying to wake Spirit up. Making a long story short, even if Spirit has started waking up, she's waking up on what is essentially a semi-random schedule and she's only waking up for 20 minutes at a time."

Meanwhile, the team's procedure involves a 17-minute communiqué that simply requests the rover to respond: "Send us a tone and tell us you're alive," as Maxwell put it. That entire 17 minute e-message must fit within the 20-minute window when Spirit is awake, which is at some random point in the middle of the day.

"So our margin for error is three minutes at some random time during the day," Maxwell explained. Therefore, while the team is reaching out and listening at different times during the day the fact remains it would be very easy to miss the rover. "If we send exactly the right command and do everything we should at Noon and she wakes-up at 12:30, we'd miss her. It would be very easy, also, to have two back-to-back attempts to wake Spirit up, neither of which works because one comes in the middle of one window and the next in the middle of another window and she's awake for half of each of them then shuts down."

Once they do get those much hoped-for tones, all they'll know for sure at that point is Spirit is alive. The goal then becomes recovering her to full operation.

Although Spirit has still not phoned home as 2010 ends, team members keep hope floating. “It’s been a tough year for Spirit,” Maxwell acknowledged. “But we are all looking forward to hearing from her, which I am confident we will in the near future."

The amount of time Spirit is awake during the day will continue to increase up to April, making "the best time" to reach her in late March to early April, suggested Maxwell. "That's when she will be awake for the longest period during the day. If we haven't heard from her by then, then I would start to get worried,” he added, pausing. "But I do expect we will hear from her before that.”

Spirit's last pic in 2010

Spirit's last pic in 2010This is the last image that Spirit transmitted to Earth before settling into hibernation on Mar. 22, 2010. This winter at Gusev Crater was particularly hash and the rover's solar panels could not provide enough power to keep her going. Unlike the landed spacecraft Phoenix, however which lost access to the Sun when it went below the polar horizon, Spirit has a chance of waking from her slumber, and NASA attempts contact daily. Credit: NASA / JPL

One real concern is the amount of Martian dust coating Spirit's solar arrays. "We just don't know anything about the dust situation on the solar arrays,” said Squyres. "It's just impossible to predict with the solar arrays. We are where we are and we will see what we see."

After the solar conjunction ends in early February 2011, the MER team plans to step up efforts to make contact with Spirit. 's listening strategies will become more aggressive. "While there are many variables in this – right after solar conjunction – between then and this peak power time, I think we are going to become increasingly aggressive in how we try to get this vehicle to respond to us, and in recovering Spirit," Nelson said earlier this week. "The frequency we are using is based on our thermal estimate of the spacecraft, so things we can do include trying different frequencies, and listening for longer periods of time," he said.

"We are still maintaining our optimism," Nelson added. "There are many reasons why we might not have heard from Spirit yet. We have things yet to do and time yet to wait.”

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

The prime directive for Opportunity in 2010 remained the same as it has been since September 2008: drive, drive, drive, stopping only for really interesting things, like craters and meteorites, along the way. The ultimate objective, as everyone following this mission knows well, is getting to Endeavour Crater.

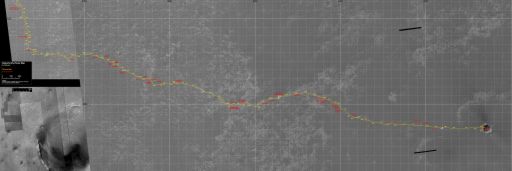

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis map -- which features images taken by the HiRISE camera and the Context Camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter -- shows Opportunity's route, along with features observed, from the twin San Antonio Craters which the rover cruised by last March to its current location at Santa Maria Crater this month. The rover will be studying the crater through solar conjunction, which ends in early February 2011. Then, it's on to Endeavour.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / MSSS / annotated by Eduardo Tesheiner

Estimated to be about 22 kilometers (13.70 miles) in diameter, Endeavour is probably the largest crater the rover will visit, promising to take the team further back in Martian time. Better than that, orbital data from MRO published in late 2009 showed the distinctive presence of clay minerals, phyllosilicates, certain evidence for past water. "The reason everyone is exited by phyllosilicates is because phyllosilicates point to water conditions with neutral pH," noted Squyres, a co-author of the paper.

From Victoria Crater, Endeavour lies some 15 kilometers across the plains by the route charted. As 2010 dawned, Opportunity was still about 12 kilometers (7.4 miles) away, in the midst of a close-up investigation of Marquette Island, a basketball-size meteorite that it had been studying since November 2009.

Once her work was done at Marquette Island, Opportunity drove on to Concepción Crater, the youngest crater she had encountered to date, “a real rubble pile,” as Squyres described it. The rover spent quality time checking out the impact site, imaging the crater rim and interior, tasting a rock dubbed Chocolate Hills, and checking out rocks in one of the dominant ejecta rays emanating from the crater.

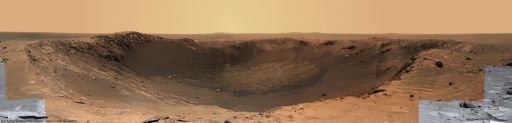

Concepcion Crater

Concepcion CraterOpportunity spent a little time checking out Concepcion Crater, up to then the youngest and "freshest" crater it had seen. That would change as the 2010 progressed. The rover took this image with its Pancam. MER poet and aficionado Stuart Atkinson added the color. Check out his Road to Endeavour blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/ Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / color by S. Atkinson

By March, Opportunity was back on the Meridiani "highway," carefully maneuvering along the outer edges of the field of dangerous ripples that sculpt the landscape, with new 'smarts' onboard. The Autonomous Exploration for Gathering Increased Science software, known simply as AEGIS, was nine years in development and served to give the rover the capability of making her own choices about whether to take additional pictures of rocks she spots on arrival at a new location, instead of having to wait for the team on Earth to decide. “It's a way to get some bonus science," explained JPL's Tara Estlin, a rover driver, senior member of the Lab’s Artificial Intelligence Group, and leader of development for this new software.

From Concepción, Opportunity cruised by craters nicknamed San Antonio West and San Antonio East, conducting some "drive-by shootings," or, in other words, taking a few pictures with her cameras as she did. En route to these "twin" craters, the rover clicked off 20 kilometers on her odometer, a major roving milestone. "The NASA requirement was 600 meters or .6 of a kilometer," Callas reminded.

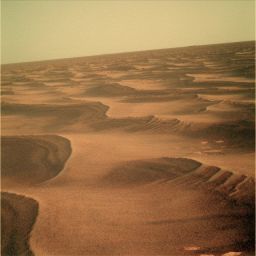

A sea of ripples

A sea of ripplesOpportunity took this mesmerizing image of the sea of ripples with her panoramic camera on her Sol 2229 (May 2 2010). The rover is doing a lot of driving around and over the sand waves these sols at Meridiani Planum.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / processed by Stuart Atkinson

Opportunity seemed to "empathize" with Spirit in April, suffering from a kind of Martian version of seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and "diminished energy," as Callas reported. With the reduced energy levels, she was only able to drive for about 30 minutes, covering just 30-to-50 meters, on a drive sol.

Although Opportunity is closer to the equator than her twin and could not have been as cold as Spirit was presumed to be, she was still experiencing her coldest Martian winter yet and it was showing. Her rover electronics module (REM) – which houses her computer or "brain," among other sensitive components – dipped to the lowest levels ever, "down around -37 Celsius" [-34.6 Fahrenheit]," Callas pointed out, with the temperature outside dropping much lower.

Opportunity continued carefully cruising over and around the rippled terrain, successfully returning the first breathtaking images of the rim of Endeavour. "The ripples look like waves on the ocean, like we're out in the middle of the ocean with land on the horizon, our destination," said Squyres.

"For my part, while the view out the windshield is beautiful and dramatic and evocative and a million other adjectives, the emotion that comes most immediately to mind is *frustration!*" Pancam lead scientist Jim Bell, president of The Planetary Society, said then. "I mean, it's going to take more than a year – maybe two years – to get to those beautiful, clay-bearing hills. It makes Spirit's agonizing three-month trek across the plains to the Columbia Hills back in winter 2004 seem like a short jog to the corner store!"

Other observers were metaphorically intoxicated, even romanticized by the view. "One day astronauts will stand at the very place where Opportunity is now," mused Stuart Atkinson, a MER aficionado and poet hailing from the United Kingdom who has been giving outreach talks on the rovers in every "drafty" church basement he can find since the mission began. "Those astronauts will be followed by colonists, and settlers, historians and tourists, then school parties and they'll all devour the view, but we – you and I – are seeing this view for the first time in all of human history. This moment will never be repeated and this picture represents a unique flashbulb event in mankind's timeline. And it's ours."

Endeavour hills in 3-D

Endeavour hills in 3-DGet you red-blue glasses and take in this version of Opportunity's first Pancam picture of the Endeavour Hills. It is, admittedly, just the first faint hint of the rim of Endeavour Crater, but it a powerful hint of just how much more is to come. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / rendered in 3-D by Stuart Atkinson

Not long after the Martian Winter Solstice passed on May 12 (May 13 Universal time), Opportunity got a little boost from Mars as the planet produced the kind of wind gusts that whisked a bit of the accumulated dust off the solar panels. The cleaning event resulted in "a 10% bump on our solar panel," informed Bruce Banerdt, MER project scientist, of JPL. Beyond giving the rover a little more power for the ongoing trek to the really big crater, the gusts also lifted a little more dust from the panoramic camera (Pancam) lenses, confirmed Bell, who recently relocated to Arizona State University (ASU) in Phoenix. "The lenses have been clearing little on and off for quite some time actually, but this time it was noticeable," he said.

Opportunity also began taking advantage of the sea of sand ripples that stretched out before her by employing what the engineers dubbed the 'lily pad' strategy. Basically, when it came time to stop after a drive, the rover would park on the northern face of a ripple to angle her solar arrays in a more energy-favorable tilt toward the Sun and bask for the rest of the sol.

Meanwhile, down on Earth, the MER operations team held it annual meeting at JPL. The discussion focused on the plan for Opportunity, "which way to drive, what we're going to do along the way, including characterizing the bedrock and the ripples, what we're seeing off the horizon, what we expect to see at Endeavour, and how that relates to what we've seen from the orbital data, juxtaposed with papers based on six and a half years worth of data," summed up Arvidson.

The Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), Context Camera (CTX), and the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), all of which are onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), have each contributed data that the MER team has used for years now to monitor and direct the rovers. With Arvidson a co-investigator on CRISM and head of the Surface Geology subteam, and Squyres a co-investigator on the HiRISE team, the team is in the immediate loop of new discoveries from on high.

Endeavour west rim map

Endeavour west rim mapThis geological map -- based on observations by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter -- indicates some of the information gained from orbital observations of Endeavour, a 22-kilometer (14-mile) diameter crater. The team chose it as the rover's destination in Sep. 2008. This map covers only a small portion of the crater's western rim. A discontinuous ridge runs north-south, exposing basalt (coded blue) and clay minerals (coded green) believed to be from a time in Martian history before the deposition of sulfates on the portions of the Meridiani Plains region that the rover found previously. Opportunity will pull into the Endeavour rim near Cape York, which is about 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) from the rover's location as of Dec. 31, 2010.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / JHU-APL

"Through CRISM, we have evidence now for putative phyllosilicate signatures from the Noachian crust, at Endeavour," said Arvidson. The Noachian epoch, between 4.6 and 3.5 billion years ago, is when the oldest extant surfaces of Mars formed, and was a period marked by numerous, large impact craters. Many scientists believe that there was extensive flooding by liquid water late in the epoch.

During that meeting, the team firmed up the decision on where Opportunity will make "landfall" at the big crater. "We're going to go to the nearest spot on the rim, Cape York," announced Squyres. "This isn't a time to mess around." As fate would have it, the clay minerals detected from orbit are not too far away.

Opportunity began the month of June however at a standstill, with a possible injury to her “neck,” something that caused the team anxiety. “We were kind of dead in our tracks, troubleshooting what we thought was a problem with the Pancam mast assembly (PMA) actuator,” recalled Squyres.

It turned out that the rover's PMA or "neck" was fine. It was the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) that was acting up. “But that was a scare,” admitted Squyres admitted. “If we would have lost that actuator, it would have meant Opportunity couldn’t turn its head."

The Mini-TES had been unusable since the global dust storm of 2007 obscured its mirrors with dust, but the team had been periodically opening the lens cover in hopes Mars would send a gust or two of clearing winds its way. For some reason, the Mini-TES failed to send a sign-off signal to the PMA, so the PMA did not move. The rover turned off the Mini-TES and the spectrometer team at ASU began working on trying to figure out what happened and why.

By mid-June, Opportunity was back on the road, heading due east toward Endeavour and making tracks with long drives. “We’re just driving and crossing ripples … 70 meters in a cloud of dust every day,” Squyres said then. “We’ve been averaging driving three times a week for the past couple of weeks,” Callas elaborated. “And we crossed the half-marathon in odometry this month, 13.1 miles. Now, we’re going to go for a full marathon.”

The Pancam views of the crater rim or the Endeavour hills, as they came to be known, reinvigorated team members. “It is so good, so nice to see details, especially in the Pancam images you can see lots and lots of detail,” offered Paolo Bellutta, of JPL, one of the mission’s rover planners (RPs). “Seeing the features on the rim makes it real now.”

That was exactly what Squyres had anticipated way back in September 2008 when the rover left Victoria. “We had to pick some direction to go," he recalled. "To the southeast was as good as anything. The nice thing about it is that rover is driving down section, giving us a good opportunity to see new rock strata we haven't seen before, so it made sense to go southeast even if we were never going to get to Endeavour. We decided that when we found interesting things along the way we would stop."

At the same time, Squyres realized something else. “It was just intuitively obvious to me – that if we had a distant goal that seemed almost impossibly far away, but not completely impossible, that if it was visible on the horizon it would sort of draw us onward, and be a wonderful motivator," he said. "As soon as we made that decision, the idea of this trek, this goal, this quest, if you will, to get to this almost impossibly far away thing with this aging vehicle that we were going to have to coddle the whole way, it was just a marvelous challenge. It just energized the whole team."

On the rippled road to Endeavour

On the rippled road to EndeavourOpportunity took this image with its panoramic camera (Pancam) on its Sol 2280 (June 23, 2010). Damien Bouic, aka Ant 103, an active member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com processed it in living Martian color.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / processed by D. Bouic

Winter lingered at Meridiani Planum in July, just as in Gusev Crater, but the Martian wind blew in to clear some of the accumulated dust from Opportunity's solar arrays. That enabled the rover to take in more sunlight and produce more power. Not only that, but for the very first time, this rover was able to capture an image of a dust devil. It was a good omen for things to come this spring.

Still around 11 kilometers (6.83 miles) away, the way the Martian ‘crow flies,’ Opportunity worked out the month by sampling some bedrock and soil to add data to the ongoing science campaign of analyzing the terrain between Victoria and Endeavour. And as July came to a close on the Red Planet, the light and warmth of spring seemed to finally turn the page on the rovers’ fourth Martian winter. The outlook looked brighter than it had in a long time.

Opportunity seemed to have the wind beneath her ‘wings’ in August as she put another half-mile behind her even with two stops to rest, conduct research, and "smell the roses,” as Callas put it. After wrapping up work on a ripple called Juneau at the top of August, the rover chalked up another 770.85 meters (0.478 mile) on her rocker bogie before stopping the weekend of August 21-22 to inspect an outcrop called Cambridge Bay.

It was around this time that the MER science team threw down a gauntlet to the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) scientists and their bigger, faster rover Curiosity. “We’re going to try and beat MSL to find phyllosilicates,” Arvidson announced. Squyres had politely presaged the race in previous editions of the MER Update, but it was made official in August if it wasn’t before: the race is on.

Phyllosilicates are minerals that form in neutral to alkaline chemical conditions, unlike sulfates, for example, which favor acidic conditions. Finding these minerals on Mars is significant because biologists view near-neutral or alkaline water conditions as more conducive to the origin of life. So, where there are phyllosilicates -- such as mica, chlorite, serpentine, talc, or clay -- there may have once been a haven for life to emerge.

Although Curiosity isn’t even at the pad yet much less off it, the race could be close – or not. The MSL rover, whose mission is to determine whether Mars ever was or is still today an environment able to support microbial life, is slated to launch in late 2011. If all goes as planned, it will rocket down to the surface at a still-to-be-determined site in August 2012.

Opportunity, meanwhile, is on her way to sites along the western rim of Endeavour Crater where the CRISM instrument onboard MRO recorded the signature of hydrated minerals, and clay minerals, specifically smectite, a type of phyllosilicate brimming with iron and magnesium. The MER luck is still working – the discovery of clay minerals was only announced after Opportunity was en route and blazing a trail to the humongous hole in the ground.

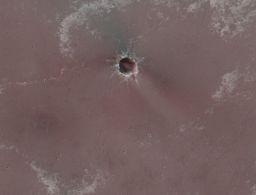

Mineral map of Endeavour's western rim

Mineral map of Endeavour's western rimCRISM spectral maps of Endeavour's western rim show smectite (red) associated with the upraised rim rocks and hydrated sulfate minerals (blue) associated with the lower-elevation sedimentary fill. The image is roughly 1.5 kilometers wide.Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / JHUAPL

In September, Opportunity picked up the pace big time. The drive limits imposed last year on the rover because of her chronic, ‘hot’ right front wheel were eased, ‘unleashing’ her to drive as much as 140 meters in one sol if possible, thus potentially doubling the 70 meters to which it had been restricted. “We haven’t been doing any drives that are getting us that far yet, but 140 meters is a number we can probably hit and it’s going to be a nice comfortable distance for us,” Maxwell said then. Past that, he added, the rover drivers are talking about some other “tricks” that would enable Opportunity to drive even farther and “faster."

Pressing on, the rover consistently and consecutively zipped along for 100+ meters in a single jaunt logging more than 935 meters or half-a-mile in October. “We’re driving across what is really one of the last large expanses of bedrock that we’re going to see,” noted Squyres. “It sort of peters out after this.” That is, he reflected, both a bad thing and a good thing. “There’s a lot of science in the bedrock and we’re not going to see much more of it for a while. But at the same time, the sand is easier driving as long as there aren’t big ripples. Once we motor past the last of the bedrock, it’s basically pedal to the metal,” said Squyres.

Endeavour was still some 8 kilometers (4.97 miles) away by the charted course, but the hills of Endeavour on the horizon continued to become ever more alluring for team members and fans alike. And, other than her old injuries -- the broken shoulder joint on her arm, the troublesome, slightly toed-in, “hot” right front wheel, and an unresponsive Mini-TES, Opportunity demonstrated the legendary MER mettle throughout 2010. Driving backwards, with her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm in a slightly unstowed position because of the broken shoulder joint, the rover roved on. Even though she was never designed to drive with her arm out, she pulled off sequenced drives and autonomous drives brilliantly, with seemingly nary a care or problem. “As long as we’re driving backward, it’s been smooth sailing,” reported JPL's Matt Keuneke, the integrated sequencing team chief and a mission manager.

Technology on Earth meanwhile marched on, and the MER mission blazed another trail as the first NASA space mission to use cloud computing for daily mission operations. A term that refers to computing capacity (space, power, speed) on demand, cloud computing is basically a method of gaining speed and flexibility in computing ability, as if from the clouds, hence the name. “You can rent the computing space and power when you need it, ordering it from a web browser so it’s self-service, and pay only for what is used," explained JPL’s chief technology officer Tom Soderstrom, of the Office of the Chief Information Officer, who spearheaded use of the industry trend at the Lab.

“The cloud is the ability to access computing power when you want it without having to own it,” Soderstrom summed up. The benefit, he said, is that MER scientists around the world are now getting the rover planning data at record speed. “We went from queries taking tens of minutes to just a second or two. And we are seeing cost savings.”

Opportunity roved on through a field of craters toward Endeavour Crater, quietly claiming title in November to being the first roving robot to drive 25 kilometers on Mars. With miles to go to get to its ultimate destination, the rover seemed content almost to just keep on driving, and she literally cruised through November, putting another 680 meters (0.422 of a mile) behind her with relative ease.

Powered up with plenty of Sun-fueled energy, the rover zipped across the landscape with 80-to-100 meter drives, snapping pictures of various craters she passed. “One of the things we want to understand is how do craters get erased on Mars?" said Squyres. "By adding images of these craters in different stages of degradation to the Mars database, we can begin to figure that out.”

Intrepid Crater

Intrepid CraterIntrepid Crater is presented here in false color to make differences in surface materials more visible. This image combines exposures that Opportunity took with its Pancam through three filters admitting wavelengths of 752 nanometers, 535 nanometers and 432 nanometers. Intrepid crater is about 20 meters (66 feet) in diameter, about the same size as Eagle Crater into which the rover bounced on landing, and where it found signs of past water.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

The MER team remembered a few of the pioneers who inspired them in November. In honor of the 41st anniversary of Apollo 12, the second mission to land on the Moon, the team members christened two craters Opportunity was imaging Yankee Clipper and Intrepid after the Apollo 12 spacecraft.

By November's end, Opportunity was on her way to the last major geologic formation on the way to Endeavour, a smaller, fresher crater called Santa Maria, about 1.3-to-1.5 kilometers away. From orbit, CRISM indicated there was a patch of ground rich with hydrated minerals, something not seen before on Opportunity's path from orbit. It was another history-making moment for MER.

Opportunity spent her sols this month racing to the end of “a good year,” as Squyres put it. “We have really been driving the heck out of this rover,” said Maxwell.

Since driving autonomously backwards requires more imaging and that fills up the rover's flash memory, another morning Ultra-High Frequency (UHF) relay pass with Mars Odyssey was sequenced and the first was executed successfully on Sol 2456 (December 21, 2010), returning 71 megabits of data. Downloading more data more frequently will allow the rover to drive even longer distances in coming sols.

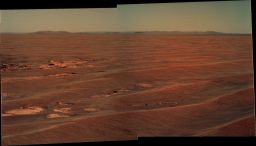

On December 16, 2010, Opportunity arrived at Santa Maria. The not-exactly-circular, 80-to-90-meter-diameter (262-to-300-foot) crater that is about the size of a football field is reminiscent of Endurance Crater. "Even though it's a bit smaller, it's fresher and even more spectacular visually," said Squyres. "We've got a much higher rim, and we have much more ejecta as a consequence exposed in the crater walls.”

Santa Maria in color

Santa Maria in colorThis is a colorized version of Opportunity's image of Santa Maria Crater. "Colour can be derived from the small 64x64 thumbnail images that are sent down first (so that the rover team can check that they we taken properly)," notes colorist James Canvin. "In this image I have overlaid this colour information onto a greyscale navcam image taken at the same spot. Quite a view!" Indeed.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / color by J. Canvin

“It's the largest, freshest crater that we've ever seen so far and it gives us a chance to map in detail the structure and morphology of a geologically young crater," expounded Arvidson. "There are ejecta rays, and ejecta blocks and it looks like the only modification has been a little bit basaltic sand that has filled up the floor. Some of it has been blown out to the northwest, but otherwise Santa Maria looks like a crater that formed fairly recently, but just how recently, we don't know."

As the end of December brings the curtain down on 2010, Opportunity is into an in-depth science campaign at Santa Maria. The plan calls for the rover to hang out at the crater through solar conjunction, the two week period beginning in mid-late January and extending into early February where the Sun will separate the Earth from Mars and communications between the two planets are limited to non-existent. In addition to documenting the crate with wide-baseline stereo-imaging from several positions around the crater, the rover will study the rocks exposed or ejected by the impact that created Santa Maria, and, of course, examine the southeast part of the rim where CRISM detected hydrated minerals.

Meanwhile, CRISM is “oversampling" Santa Maria. Last fall, the instrument began using a pixel-overlap technique that promises to provide even better resolution of what's there. "We're overlapping to get multiple views of the same site," explained Arvidson. "Imagine that you have a whole bunch of 18-meter circles that are spaced maybe 6 meters apart along the outcrop. In the along-track direction, you can re-process the data to make it sharper. It is a work in progress. We're planning to coordinate data with Opportunity and CRISM. We'll get day-and-night data and we'll get color HiRISE images."

Anaglyph of Santa Maria Crater

Anaglyph of Santa Maria CraterA red-blue anaglyph of the 100-meter-diameter Santa Maria Crater, where Opportunity arrived on Dec. 16, 2010. Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / anaglyph by Marswiggle

The scientists don't really expect of find any strange new Martian mineral. “It's probably the same mono-hydrated sulfates we've seen elsewhere on the planet but nowhere Opportunity has been,” noted Arvidson. “It's not that we expect to identify a new mineral, but it is the first time we're seeing hydrated minerals from orbit here, and the question is why. The idea is that Santa Maria is so fresh that it hasn't been coated. So this is getting at the weathering of the rocks. That's the working hypothesis." Squyres agreed: "Santa Maria combines Mars size and freshness to a greater degree better than any place we've ever been with this rover yet, so,", "I suspect it does have to do with how fresh the crater is."

One leading theory is that CRISM has detected kieserite, a hydrated magnesium sulfate (MgSO4·H2O) that is typically abundant in evaporite deposits. “If it's kieserite, then Mini-TES, before it stopped, inferred the presence of kierserite for other parts of the outcrop," noted Arvidson. It won't be long before they know for sure.

From Santa Maria, Opportunity will head straight on to Endeavour, with only a handful of planned stops along the way. “When we set out from Victoria [in October 2008], Endeavour seemed impossibly far away," recalled Squyres. Because the rover would have to divert from a straight-shot course to avoid the largest ripples or purgatoids in the field of ripples along the way, the path chosen was approximately 15 kilometers (9.32 miles) and the rover team has made some changes and adjustments along the way, extending the distance driven even further. Now, the rim is coming into better view with every week that passes. "While Endeavour is still a very distant 6.5 kilometers," he noted, "it doesn't sound impossible.”

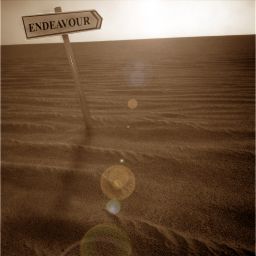

Onward

OnwardOpportunity put the pedal to the metal in Oct. 2008, leaving Victoria Crater, its home for two years, for good. The rover is now just 6.5 kilometers from what back then seemed like an almost impossible dream. This image, which the rover took with its Pancam was enhanced with humor by Stuart Atkinson.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / S.Atkinson

“It was a hope that now it seems realistic,” summed up Arvidson.

Anything can happen anytime, of course. This is Mars and the rovers are machines. “Opportunity has been stressed as much as it ever has been in any given year since landing, and yet it continues to exceed our expectations," said Nelson. "While past performance is no guarantee of the future, if past performance is our guide, we should make to Endeavour in 2011.”

“I happen to think there is nothing to slow Opportunity down,” added Maxwell. “Opportunity has had a terrific year. She has performed just absolutely beautifully and she continues to perform absolutely beautifully."

In fact, Opportunity blew away her own 2009 record of 5.310.23 kilometers (3.299 miles) this year, putting 7.578.08 kilometers (4.709 mi) behind her -- more kilometers (miles) than in any other single Earth year.

"As amazing as 2010 has been, I really think next year is going to be even better," Maxwell predicted. "And that's a heck of a thing to be saying seven years into a 90-day mission.”

Making it to Endeavour would be a hugely significant mission milestone, an astounding achievement actually. "I'm making no predictions," Squyres said. "But," he added, "we are 6.5 kilometers away with a rover that drove more than 7.5 kilometers this past year. You do the math.”

With the dawning of another New Year, the MER mission is roving on.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth