A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 31, 2009

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Perseveres Struggles, Opportunity Digs in at Marquette Island -- And We Look Back on 2009

The Mars Exploration Rovers quietly wrapped up 2009 this month: Spirit continued to valiantly spin its wheels in an attempt to get out of its embedded location on the west side of Home Plate in Gusev Crater; and Opportunity continued its investigation of Marquette Island, perhaps the oldest Martian rock it's found to date at Meridiani Planum.

Spirit, which has been mired since last April in the sandy soils of Ulysses at a place dubbed Troy, made very little progress in its objective of driving out of its dilemma in December. The prospects of it achieving that goal didn't get better. The rover’s right rear wheel, which had been repeatedly stalling in November, was declared inoperable late this month, a loss that further stacked the odds against the little rover.

“We’d like to drive completely out of Troy, but we’re not sure that’s possible before we have to settle in for winter,” said Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis, during an interview earlier this week. “The egregious issue is that we’ve got two drive wheels on the left side that are deeply embedded, middle wheels on both sides that aren’t gripping, and a front and rear wheel on the right that aren’t helping,” he lamented, reluctantly admitting that there is a good chance now that the rover won't ever be able to free itself.

Arvidson, who has handled the day-to-day directing of Spirit’s science research, while Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, directs Opportunity’s science meetings and oversees all rover science, is partial to his charge but not as optimistic as he was just last month. "Spirit's in a tough situation," he summed up.

“It's a very complex situation, very difficult situation for the rover,” assessed MER Project Manager John Callas, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were designed and built, and are being commanded. The right rear wheel is apparently no longer working and with its right front wheel out of commission since March 2006, Spirit has only four dependably operable wheels. “If it was questionable as to whether we could get a five-wheeled rover unstuck, it's certainly even more questionable as to whether we can get a four-wheeled rover unstuck,” Callas pointed out. “We basically have no experience driving a four-wheeled rover either on Earth or on Mars,” noted Squyres.

At the same time Spirit’s right rear wheel stopped revolving, the MER engineers detected a problem with the electrical mobility system on the rover and suspected the motor control board, the 'motherboard' for the mobility actuators or motors

Simulation of Spirit's predicament

Simulation of Spirit's predicamentThis artistic image -- in which Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover -- illustrates Spirit's predicament at the location in Gusev Crater known as Troy. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers the casual reader a glimpse into the present scene on Mars -- and this rover scribe thinks it's a pretty cool illustration.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

Still, Spirit persevered through December, making a few centimeters of progress for all its efforts and carrying out diagnostics tests, including electrical resistance tests on all the wheel actuators (motors). Amidst those tests on December 12 -- wonder of wonders -- the motor for the right front wheel -- which has been out of commission since March 2006 -- came on board. Three sols later, Spirit gave the team a big surprise.

“We turned the motor for the right front wheel and it worked,” Arvidson recounted. The wheel did a number of rotations and, “even had traction and was trying to pull the vehicle forward,” he said. “It did dig in a little bit.”

“That was completely unexpected,” said Callas. “Suddenly it's working. It's not completely dead.”

The rover hasn’t done much with its right front wheel since then, although it has followed commands to turn it on and the wheel starts to rotate. After a couple of seconds, however, “it just stops,” Arvidson reported. Still, that Spirit’s right front wheel is moving at all seems downright weird. Weird enough to assess whether or not that wheel might have a little life left in it. Weird enough to keep the faith.

When Spirit spun its wheels the day after that though, on its Sol 2117 (December 16, 2009) neither of the troubled wheels helped and the rover again went nowhere. It did, however, discover a persistent, negative voltage, known as a single-point ground, between the robot’s electric ground and its chassis, where no voltage should exist. That, the engineers say, points to some sort of electrical short to the rover chassis. It also supports their contention that this and other unusual electrical behavior means there is trouble with motor controller board, something pretty well confirmed as they tested and saw unusual behavior with all 10 motors associated with that electronics board.

It was a logical deduction, especially considering that other motors not related to the wheels seem to be okay. The motors controlling other parts, like the robotic arm, the Pancam mast assembly, and the high gain mast antenna, in fact, were each tested and "they were fine," noted Callas. “It makes for a very complicated story here for what's going on with the mobility system," he said. “The reality here is we have a rover that is well past warranty and things are wearing out."

Meanwhile, with the Martian winter on the horizon, the temperatures are beginning to fall and the Sun is rising and setting lower in the sky; consequently, Spirit’s energy levels are dropping. “The issue for Spirit now is not only extrication, but also survival through the next winter,” said Callas. “The depth of winter is still five months away, but we’re looking now at what it can do to maximize the survivability of the rover.”

Right now, Spirit is embedded with its solar arrays pointing to the south about 5 degrees. Since the rovers cannot tilt their solar arrays, they have to physically move position to angle their arrays toward the Sun. If Spirit can move forward just a little – a "wild guess" suggests "15 centimeters or so,” Arvidson said -- the rover could be tilted 5 degrees more to the north. Just moving that much would make for a “more comfortable” winter, he said.

If Spirit can’t move, if it can't get more northward tilt, the rover can still survive in its current position with what power it has, according to Callas and Squyres. A series of dust clearing gusts earlier this year that pretty thoroughly cleaned Spirit’s solar arrays are now making survival possible. "But it's going to be close,” said Squyres. “When we run the projections forward, Spirit can make it, but we're right on the ragged edge of survival.”

“As we trend the dust accumulation through the winter, we think Spirit could survive with something on the order of 150 watt-hours of energy -- if we turn off the heaters for the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES),” elaborated Callas. The rover has a little less than double that right now and solar power production on Mars is contingent on various factors. The scenario could change in the blink of an eye if more dust falls onto the rover’s solar arrays or if the temperatures outside get colder than expected or if the atmospheric opacity gets denser than anticipated.

Right wheel turning

Right wheel turningThis three-frame animation shows the performance of Spirit's right-front wheel during a drive on its Sol 2117 (Dec. 16, 2009). This wheel, on the right side of the images, had stopped operating in March 2006 and had not been used for driving since then. However, it revolved with apparently normal motion during the first three of four driving segments on Sol 2117. It completed about 10 rotations, then it stopped early in the fourth segment of the drive. The three wide-angle views shown one after the other in this animation come from Spirit's front hazard-avoidance camera and were taken at different stages of the Sol 2117 drive. The most obvious change is in the position of shadows, a change unrelated to the wheel's movement during the drive. The frame with the rover arm's shadow farthest to the left is the first image in the sequence of three. The view is northward.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

From the looks of things – and especially considering that the Martian winter won’t reach solstice until mid-May 2010 – Spirit needs a miracle. Where this kind of situation would surely speall ‘curtains’ for other robots, the MERs have miraculously survived all kinds of threats, from the largest solar flare on record during their trip to Mars to a global storm that dusted the planet in 2007, and thousands of harsh thermal cycles that vary temperatures as much as 100 degrees in a single sol.

Not only that, the beauty of the resilience built into these solar-powered rovers is that even in the worst-case scenario, if Spirit depletes all the power in its main batteries, for example, it can still “resurrect” come spring. “As long as something doesn't break on the rover, it can be quiet for a long period of time, and then -- even if Spirit has been completely depleted, to the point of where the clock doesn't even operate -- if it gets enough sunlight on the solar arrays it can wake up. It can boot up. Much like if your alarm clock doesn't work, you wake up when the Sun comes streaming in your window.”

And, if Spirit cannot get out of Troy with four operable wheels and is ultimately declared permanently stuck, it can still live on as a fully active lander. Everyone agrees that there is still a significant amount of work for the rover to do from where it is parked now. That's why no one can give up yet.

In any event, the MER team is prepared. Science team members have outlined a fall-winter science campaign for Spirit that consists of three primary areas of study:

- A radio science analysis to “accurately define Mars’ polar rotation,” which will help reveal more about the planet’s interior;

- A continued study of the atmosphere and surface to better inform scientists about Mars' current environmental and climatic conditions; and

- Remote sensing of geologic formations in the surrounding area, including von Braun and Goddard, the mound and large pit that have long been Spirit’s next major attractions.

Spirit at Troy

Spirit at TroyThe little white dot on the left side of this image is Spirit sitting in the sandy soils of Ulysses on the western side of Home Plate in an area the team calls Troy. This image was taken erlier this year by the University of Arizona's HiRISE camera, which is onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

The science campaign will begin slowly, Arvidson said, "between drives."

“We are not focusing on that science campaign now, because we're still trying to get the rover out," Squyres underscored. “We've still got a few tricks up our sleeves and until we've exhausted all the possibilities, that's going to be the focus. If at some point it becomes obvious that every trick we've got is not going to work, then we will shift our attention to maximize the science of a stationary vehicle, but the focus now is still mobility.”

All in all, 2009 was a year of increasing physical challenges for Spirit -- “the toughest year on record for this rover in terms of mobility,” Arvidson noted. "I's hardly surprising that we've gotten stuck as we have,” added Squyres. “We just don't have the six-wheeled mobility system these things were designed to operate with.”

Spirit being Spirit, that’s been easy to forget. “We lost the [use of] the right front wheel on Sol 800 and have been mobile for many, many hundreds of sols after that, making important discoveries, including the most important discovery the rover ever made [near pure opaline silica] because of that broken wheel," Squyres noted. "So yeah, it's easy to lull yourself into thinking, it's perfectly able to work as a five-wheeled vehicle. No, it's not the way these things were designed to work at all,” he pointed out.

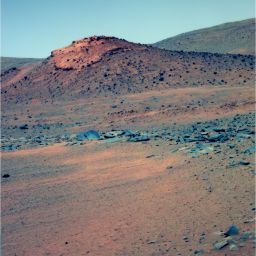

Von Braun

Von BraunSpirit snapped this picture of von Braun on its Sol 2114 (Dec. 13, 2009) with its panoramic camera (Pancam). The rover and its team had hoped to have gotten to this geologic formation long ago, but 2009 proved to be a year of challenged mobility for this rover. Spirit remains embedded in the sands of Ulysses at Troy, where it has been since last April with this view of its elusive next-big-destination. Von Braun may be what's left of an old volcano and given this rover's findings that would not be too surprising.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

In fact, Spirit spent the entire year trying to get around Home Plate and to the large pit and intriguing mound about 300 meters to the south named Goddard and von Braun, respectively.

As 2009 rang in, the rover was preparing to back down the northern edge of Home Plate after spending its third Martian winter there. The initial plan had been to inch back up on top of Home and take the short cut across the circular plateau to the other side, but with its broken right front wheel that was just not possible.

"It was a little bit of a disappointment not to have made it up onto the top, but it was not unexpected," Bruce Banerdt, MER project scientist, of JPL, said then. “We were sitting on a 30-degree slope and that is challenging driving even with all six wheels.”

After roving down, Spirit set out toward the next big attractions, taking the long way around Home in order to avoid troublesome terrain. By April, Spirit was only about half way to its dual-destination and by the end of that month, it had encountered the sandy soils of Ulysses at Troy. It was ordered to stop in its tracks in early May and it's been there ever since.

“We've spent an enormous amount of Spirit's time over the past year kind of bogged down and figuring out how to deal with it,” added Squyres.

“The counterpoint is we're embedded in a geologically very rich site,” Arvidson said, picking up the review of Spirit’s year. The MERs main mission was to ‘follow the water’ and to that end, Spirit brought home the gold again in 2009.

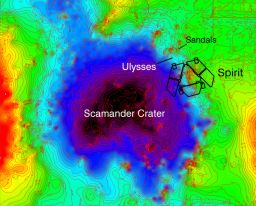

Topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy

Topographic map of Spirit's location at TroyThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed based upon Spirit's camera images of the location, taken before it got mired at Troy. The topographic model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State University

In August, Arvidson realized that the rover was actually right on the edge of a small, shallow, sand-filled crater the team would dub Scamander. Sitting astride “two timescales with evidence of water interacting with the rocks and soils,” the rover somehow, fortuitously, really had found just about the best place around to encounter its potentially mission-changing predicament. What were odds of that?

“It's becoming clear that material in Scamander Crater is of hydrothermal steam vent origin, but it's also been systematically altered from the top down and the more soluble sulfates have been moved down. It's probably post-volcanic and probably associated with times when the equator was covered with snow. So, we have solid state greenhouse effect and it's got these thin films of water moving the more soluble salts further down into the sections. It’s a pretty great place to be embedded,” Arvidson reiterated one more time. “But, I sure as hell wish we could get out of there,” he added, echoing the sentiments of the entire team.

"We've been living on borrowed time with Spirit ever since we lost the right front wheel back in 2006,” Squyres said, pausing to reflect. “This rover has been in tough spots since then. Maybe we'll get out and maybe we won't.”

Bleak as the outlook may be, no one is ready to give up. In fact, Spirit has the whole world on its side. The MER team has enlisted robotics and mobility research experts from coast to coast and across the Pond.

“Holy smokes!” Arvidson exclaimed. “We have canvassed the whole engineering community involved in mobility research, including people on our review board who are experts, the lunar mobility community from the Johnson Space Center in Houston, and other NASA centers, and now folks at the various NASA centers involved in mobility research and two groups at the DLR, the German space agency -- and anyone and everyone in the field of terra mechanics, the study of deformable soil. We’re not doing this in isolation by any means,” he said. “We're getting as much advice as we can muster and everyone's still scratching their heads and saying we have a difficult problem.”

The year ends for Spirit with many unknowns, but as 2010 sets in, what is known is this: Spirit will keep on keepin’ on. “The prime directive for now,” said Squyres, “is to try and get this rover free.”

While the world on Earth below rushed into the winter holiday season, Spirit and Opportunity forged ahead slowly, steadfastly on ‘auto-pilot’ carrying out a five-sol plan that allowed its team to take December 23-27 off for the holidays.

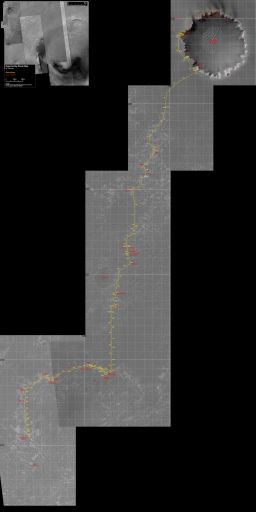

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis image, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) was labeled by rover affciando Eduardo Tesheiner to chronicle Opportunity's route from Victoria Crater to Endeavour Crater. This map shows Opportunity's travels up to Marquette Island, which the rover is currently investigating. For Opportunity, Marquette is, according to P.I. Steve Squyres, the "most exciting find in 2000 sols." Tesheiner is a senior member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / Eduardo Tesheiner

Opportunity spent the entire month of December at Marquette Island, where it’s been since early November. The rover pulled off the Meridiani highway to rest its wheels, but it wound up finding that Marquette Island may be the coolest and oldest Martian rock it’s found on the whole mission, with the possible exception, Squyres noted, of Bounce Rock. That’s the rock that the rover hit when it bounced down to the surface and later checked out back in 2004. Thus, Marquette Island is a perfect scientific cap to a year of good roving -- and it made for Opportunity ending the year much like it started it, in a mellow, studious mode.

Opportunity was quietly finishing up research at Crete as 2009 dawned at Meridiani Planum. It was the first of the rover’s soil/bedrock studies that it’s conducting all along the route to Endeavour Crater. After that, the rover took off, putting more than 5300 meters (3.3 miles) on its odometer this past year, cruising along at a pretty decent clip on its long journey, especially considering its right front wheel began last spring to show the strain of its long 100-meter jaunts sol-after-sol.

The motor to that wheel, to be specific, began drawing more current normal as the rover raced across the plains and along the edge of a purgatoid field. Here and there, Opportunity did have to stop to rest that “hot” wheel. But, as this rover's luck would have it, there was always a choice bit of bedrock, intriguing cobble or crater nearby for the rover to check out while it cooled its wheels.

“We've put a lot of mileage behind us. We found three iron meteorites – Block Island, Shelter Island, and Mackinac Island," Squyres chronicled. "That was a big surprise, especially all the weathering these meteorites showed. Then we found Marquette Island.”

Opportunity first spotted Marquette Island in late October, after roving upon the three meteorites amidst the cobbles that dot the Meridiani landscape. As interesting as the meteorites are, they’re ultimately from someplace else. Marquette, though, is Martian and that makes it an important, textbook-informing discovery. Even as the rover’s investigation of the rock began in November, it was looking like it might be one of the most significant discoveries on the mission.

A magical meteorite tour

A magical meteorite tourThis image -- put together by Stuart Atkinson, a moderator and the "Poet Dude" at UnmannedSpaceflight.com -- shows the four iron-nickel meteorites that Opportunity has found: counterclockwise Shelter Island, Block Island, Mackinac, all discovered this year, and Heat Shield Rock, which it found back in 2005.Note: This image is not to scale.Atkinson posts his pictorial efforts and his poetry on a blog called The Road to Endeavour. Check it out at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / assembled by Stuart Atkinson

There’s nothing like the real data, so the scientists had Opportunity rove around the rock and take pictures from all angles, with the panoramic camera (Pancam) and the microscopic imager (MI), and to move in close enough to study the composition with its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS).

That data in hand, the team decided that before Opportunity hit the road again for Endeavour Crater, it should use its rock abrasion tool (RAT) to grind into Marquette.

During the second week of December, the rover positioned itself to do just that. It nuzzled up to be able to reach the surface target called Peck Bay, where it previously had done some compositional analysis. By its Sol 2093 (December 13, 2009), it was ready to rock, err grind.

“We've completed 1.5 millimeters of grinding on Peck Bay,” Squyres announced earlier this week. On its Sol 2109 (December 29, 2009), Opportunity was slated to take the RAT away and take pictures of the grind spot with the MI, “to see how well we did,” he added. “Then we're also going to image the RAT bits to see if we can get a sense of how much RAT bit capability we lost in doing the grind.”

There is no way for the rover to tell exactly how old the rock is, Squyres said, but the compositional analysis completed this month seems to support the leading hypothesis that Marquette Island came from deep down under, expelled from beneath the surface during an ancient impact. From the miles and miles of tracks laid right up to Marquette, 2009 was “a real good year for Opportunity,” he summed up.

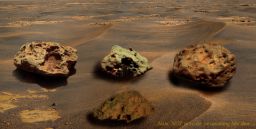

Marquette Island

Marquette IslandFrom a distance, scientists at first thought Marquette Island -- rendered here in near-true color by MER enthusist Stuart Atkinson -- might be another meteorite. Now, they think it was hurled up from deep beneath Mars'surface by an ancient impact. Opportunity has spent the last two months checking it out as it takes a break from its long journey to Endeavour. You can see more of Atkinson's enhanced images at his blog, The Road to Endeavour at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / enhancement by Stuart Atkinson

Despite the physical challenges the senior robots confronted, 2009 will no doubt be remembered as a year of great discovery for the Mars Exploration Rovers, notably Spirit’s further confirmation of the presence of volcanic steam vents and water-impacted rocks at and around Home Plate and, of course, Opportunity’s discovery of Marquette Island.

Through it all, the rovers produced a lot of new data and thousands of new pictures this past year, while continuing to blaze new engineering trails.

Now, as December 2009 fades to history and the twin robot field geologists cruise toward the end of their sixth Earth year of exploring Mars, the end of the sixth year of the first robotic overland expedition of another planet, they are, aches and pains and breakdowns of aging aside, in remarkably good health.

Spirit and Opportunity both still sport plenty of 'right robot stuff' and each is producing enough solar power to celebrate their anniversaries in true MER style next month – by working and roving on. Which, actually, gives pause for thought … with everything that went wrong down on Earth in 2009, up there, on Mars, Spirit and Opportunity 'went right.' Priceless.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth