A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 31, 2008

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: As Spirit and Opportunity Rove On, We Look Back on 2008

As 2008 fades to the pages of history, Spirit and Opportunity are closing in on the end of their fifth year of exploration on the Red Planet and moving the Mars Exploration Rover mission forward into a new year of bold scientific objectives.

"They have continued to succeed beyond our wildest expectations,” said Steve Squyres of Cornell University, principal investigator for the rovers’ science instruments, during an interview earlier this week.

After finding signs of past water both above ground and underground during their three-month primary mission in 2004, the twin robot field geologists have continued since then to fill out the stories of past environments at Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum, expanding knowledge about the planet that has forever captured human imagination, roving on from discovery to true exploration.

“The journeys have been motivated by science, but have led to something else important – humanity's first overland expedition on another planet,” Squyres summed up. “When people look back on this period of Mars exploration decades from now, Spirit and Opportunity may be considered most significant not for the science they accomplished, but for the first time we truly went exploring across the surface of Mars."

Despite the fact that 2008 dawned into dusty skies – the residual effect of the life-threatening global storm of 2007 that nearly took out Opportunity – the twins carried on, underscoring how longevity and the ability to move from one scene to another can magnify the science and engineering return of a planetary mission.

The resilience and stamina of the MERs enabled the robots and their ground crews to take full advantage of data from state-of-the-art instruments sent into Martian orbit onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) long after they landed, something that has helped further advance planetary exploration. With incredible images of the terrain snapped by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera, so detailed they show the rovers on the ground, and periodic weather reports from the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) instrument that takes long broad view images of the planet, the MER team has guided Spirit and Opportunity with a kind of precision once only imagined.

Spirit explores Home Plate

Spirit explores Home PlateMore than a year of Spirit's examination of the eroded over volcanic plateau in Gusev Crater known as Home Plate is chronicled in this animation of nine images from the HiRISE camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The images cover an area approximately 100 meters square. The geometry of Home Plate appears to shift from image to image because the orbiter often had to turn to one side or the other of its orbital track across Mars in order to view Spirit, so usually saw the raised topography of Home Plate from a point that was not directly over the rover. However, some of the apparent shifts in features are also real shifts in the distribution of dust around Home Plate with shifting winds and seasons. The global dust storm of summer 2007 almost completely blocked the view of Spirit at one point during the animation.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / Doug Ellison

The team itself made history on February 22, 2008 when women took the wheel. The entire tactical operations team for the mission that day, both onsite at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were designed and built and are being managed, and offsite at the various remote institutions, was comprised of women. “It was fabulous," said Cindy Oda, mission manager. "Women are driving on Mars and commanding rovers."

The most notable achievement for the mission this past year, however, has to be that both Spirit and Opportunity survived their third Martian winter, something that no one on the team back in 2004 when Spirit and Opportunity landed ever believed possible.

For Spirit, 2008 was pretty much all about surviving. Despite the odds against it, the intrepid MER-A held on through the brutally cold Martian winter, perched on the northern edge of Home Plate, a circular, eroded over volcanic formation. Ultimately, it recorded the lowest power levels to date on the mission – not during the winter as had been anticipated, but as a result of a dust storm that struck it dead-on in early November.

Spirit demonstrated the MER mettle once more, following power conservation instructions and phoning home right on schedule. As Sharon Laubach, MER’s integrated sequencing team chief at JPL, put it then: “It’s going to take a lot to put that rover down.”

Although Spirit remains coated in dust and power challenged, it is roving on as 2009 rings in, backing down off its winter perch on the northern end of Home Plate and heading south to two formations that have long intrigued the team, an unusual pit the size of a house and a mound, named, respectively, for rocket pioneers Robert Goddard and Werner von Braun.

The women who took the wheels

The women who took the wheelsOn February 22, 2008, the entire tactical operations team for the Mars Exploration Rover mission, both onsite at JPL and offsite at remote institutions, was female. Standing left to right:

On the other side of the planet, Opportunity devoted most of 2008 to completing its two-year investigation of Victoria Crater, a site that five years ago was considered an “impossible” target. In mid-October, the rover set off on what just may be the journey of its lifetime, a 12-kilometer (7.5-mile) trek to a crater 20 times bigger than Victoria, a monster-sized hole in the ground the team dubbed Endeavour.

The decision was a highpoint of the year, because “it has shaped the future of Opportunity’s mission in a fundamental way,” Squyres said. Endeavour is 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) away from Victoria. That is the same distance that Opportunity had driven all told since landing. But neither team nor rover wasted any time proving their determination. By the end of November, the rover, in six short weeks, put 1.25 kilometers (0.77 mile) on its odometer.

Throughout the year both Mars Exploration Rovers passed their physicals and despite a few physical ailments and signs of aging – not the least of which was the loss of the shoulder joint on Opportunity’s arm – all subsystems on each vehicle generally performed as expected. Consistently, Jake Matijevic, chief of rover engineering at JPL, reported: "Spirit and Opportunity are doing fine.”

Threats to rovers, however, can come from Earth as well as Mars and in 2008 the mission dodged a serious monetary pothole. A directive from NASA headquarters in February ordered JPL to reduce the cost of rover operations by $4 million, something that would have resulted in the plug being pulled on one of the twins and a number of team members being let go. But, fortunately for the mission, the orders had not been "fully coordinated" with the NASA Administrator and thus were never put into effect.

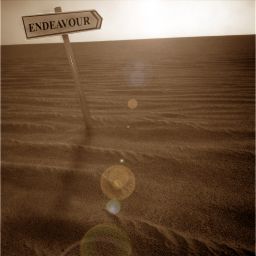

Onward

OnwardOpportunity put its pedal to the metal in October and left Victoria Crater, its home for the past two years, for good. It made a number of 100+-meter drives and nearly broke its own record that month when it logged a 216-meter drive. This image, which the rover took with its Pancam was enhanced with humor by Stuart Atkinson, a space exploration enthusiast and active member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Stuart Atkinson

Spirit and Opportunity went into a two-week communication blackout at the end of November because of solar conjunction – a biannual celestial event where Earth and Mars orbit into positions on opposite sides of the Sun. In this planetary configuration, communications between the two planets are disrupted for about a two-week period, so the rovers worked on autopilot.

Bent on conserving what little power it had, Spirit worked a scant 15 minutes a day only checking the dust in the sky and its own power supply, while Opportunity homed in on the composition of a cobble called Santorini.

On December 14, both rovers emerged from the communications blackout in fine form, all things considered. “Both Spirit and Opportunity are in good health, though they have a lot of onboard data we’re working to get down,” reported John Callas, MER project manager at JPL.

As the lights of the season blink out and the world down on Earth struggles with a global economic recession, up on Mars Spirit and Opportunity rove onward undaunted, toward exciting new destinations and another year of exploring, demonstrating the robot right stuff in full, reflective titanium glory, showing that dreams – beyond which we could ever imagine – can come true.

Solar conjunction

Solar conjunctionAbout every 26 months, when Mars and Earth are on opposite sides of the Sun, the Sun blocks communication. This celestial event is known as solar conjunction.

Although the rovers get a lighter workload, Spirit monitored atmospheric dust and Opportunity studied the atmosphere and the chemistry of a small rock known as a cobble.Spirit and Opportunity began talking to Earth and Earth began talking to the rovers on December 14, after a two-week silence. Credit: NASA / JPL

Spirit from Gusev Crater

Just before the Christmas holidays in 2007, Spirit pulled up to the northern edge of Home Plate, the eroded over volcanic formation it had been working on and around for more than a year. With the Sun rising and setting lower in the sky, Spirit – which is further from the equator than is Opportunity over on the other side of the planet – had to get onto a slope where it could tilt its solar arrays directly toward the center of the solar system in order to survive the dreaded season. The northern slope of Home Plate fortuitously offered just such a haven.

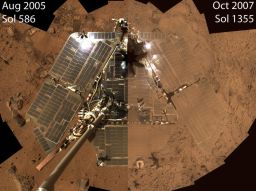

A dusty start to Spirit's third Martian winter

A dusty start to Spirit's third Martian winterThis image juxtaposes two "deck pans" the rover captured with its panormaic camera (Pancam) at different times during the mission. On the left is the self-portrait from the top of Husband Hill, when the rover's deck was nearly as clean as the day it landed. On the right is a view it took in September 2007 following the summer's global dust storm. Dust from the sky settled on both the rover deck and the surrounding landscape, nearly camoflauging it in the rusty terrain on which it was parked before it roved to the northern edge of Home Plate.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell

Over the next several weeks, it would inch backward down the slope, over the northern edge repositioning itself as it went and conducting what science it could before it settled in to ride out the season. But, as 2008 rang in, a cloud of uncertainty hung over the solar-powered rover’s prospects for surviving its third Martian winter. The accumulated dust on its solar arrays was blocking more than 65% of the sunlight shining down – meaning, Spirit was only able to utilize 34% of what was available to fuel itself. It had been some six months since it had experienced a gust of dust-clearing Martian wind and the rover was so dusty now that it was blending into the rusty red terrain.

Nevertheless, in January, Spirit completed the Tuskegee Panorama, named in honor of the Tuskegee Airmen, the African American pilots who flew the red tail P-51 Mustangs to fame for America in World War II, as well as an in-depth investigation of Chanute, a target on the top surface of the Home Plate stack of stratigraphy.

As the rover worked, an image among hundreds that Spirit had previously taken for the West Valley Panorama began circulating on the Internet and the MER mission was suddenly back in the news. Some thing – distinctly rusty red like the terrain but resembling the mythical Big Foot – appeared to be making its way through the Columbia Hills. For a couple of minutes, the image seemed to take on a life of its own. Everyone seemed to have a good laugh, as if space exploration – beyond the grand, singular feats – is only worthy of news when some something weird turns up.

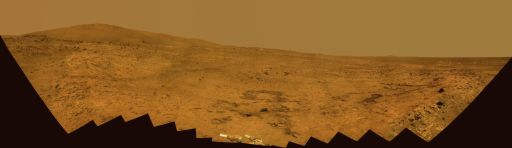

Tuskegee Panorama

Tuskegee PanoramaSpirit finished taking the hundreds of images required to make the Tuskegee Panorama in January 2008 and Panoramic Camera lead Jim Bell, now president of The Planetary Society, mosaiced those images into the finished product. The rover took the images from Sols 1412 to 1428 (Dec. 23, 2007 to Jan. 8, 2008) as it moved into place off the edge of Home Plate North, its third winter haven. This vantage point provides a particularly good view of the rugged top of Home Plate.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

In reality, “Big Foot” was a couple of rocks, no bigger than about 2 inches. “It must have been a slow news day,” Squyres sighed. At the end of the week, however, the West Valley Panorama became one of the most downloaded from the entire MER mission. "The JPL photo servers were just about brought to their knees by everybody trying to download this image," reported JPL’s Bruce Banerdt, MER project scientist.

Sporting a modest 260 watt hours of power – the rovers boasted around 950 watt-hours of power shortly after landing in 2004 – Spirit kept up with its science agenda as it made several short moves to nestle into its winter parking spot, making its last “bump” on Sol 1464 (February 14, 2008). There, with its front two wheels barely on the rim of the circular plateau, the rover’s solar arrays tilted at 29.9 degrees, about as far as it could safely go and still conduct science, according to Matijevic.

The Martian "Bigfoot"

The Martian "Bigfoot"Here is the image of that many people believed resembled "Bigfoot" or Sasquatch. It caused a veritable stir on television and the Internet in January 2008. Turns out that the Martian "Bigfoot" is comprised of two Martian rocks spotted by a jokester looking at Spirit's West Valley panorama.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Spirit would not move again for eight months, but it would not sit idle. In addition to keeping a close eye on the dust in the sky, the rover was assigned a winter science campaign, the centerpiece of which was a 360-degree panorama to be stitched together from more than 2,000 individual images snapped with the panoramic camera (Pancam).

Expected to be a panorama so rich, it was named in honor of beloved space artist Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986), who inspired an entire generation of astronomers, artists, writers, engineers and visionaries with his remarkable paintings.

To get the desired mural, Spirit would have to take 27 columns of images with its stereo camera system, from the foreground to sky. The rover would take each of the some 2,000 pictures "at low compression levels” and with all the camera’s filters, according to Planetary Society President Jim Bell, Pancam lead scientist, of Cornell University.

In February, Spirit made progress with its investigation of the layers or strata of bedrock that form Home Plate, finishing work on Freeman, named after the airfield in Indiana where the Tuskegee Airmen staged historical protests for civil rights, and began work on Wendell O. Pruitt, named for one of the renowned fighter pilots from St. Louis, Missouri. "The focus here is to try and understand the Home Plate stratigraphy," noted JPL’s Diana Blaney, deputy MER project scientist.

By March, however, Spirit was officially put on a reduced, winter operations schedule. The rover would get up each workday and put in 1 to 1.5 hours, then spend the following sol just recharging its batteries. Its prime directives became routine atmospheric observations and taking the Pancam pictures for the huge Bonestell Panorama.

Spirit settles in at Home Plate

Spirit settles in at Home PlateHuman explorers would be hard pressed to show more persistence than Spirit. After weeks of careful driving backwards dragging its broken front wheel, the rover finally made it to what team members call Home Plate North. It then gradually descended over the edge to get into position, as shown here, tilting its solar panels 13 degrees toward the sinking winter Sun to maximize its intake of light. Rover drivers plan to continue nudging Spirit forward, increasing the tilt, to track the Sun as it moves lower in the northern sky. The full-resolution version of this animation can be downloaded here (9.2 MB).

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Winter winds began blowing into Gusev in April, but Spirit continued to fare well, maintaining a respectable amount of energy due to a couple of factors. For one, the skies continued to clear of dust. Also, the rover just didn’t get as cold as the models had predicted.

Since it is further from the Martian equator than Opportunity, theoretically, Spirit should have been experiencing colder temperatures than it’s twin, but its parking spot on the side of a bedrock rich site where there is more rock than soil was believed to be actually a little warmer than the terrain on which Opportunity was working inside Victoria Crater, for the simple reason that rocks absorb the heat of the day and hold onto it longer than soils.

Still, both Spirit and Opportunity were experiencing cold beyond our human comprehension, downward of -95 degrees Celsius (-139 Fahrenheit).

With its power levels hovering around 237 watt-hours, the odds for Spirit’s survival improved significantly and team members heaved a collective sigh. "We generally are pretty pleased with Spirit's performance,” said Matijevic, who noted that the JPl engineers had passed the point of having “to do anything extraordinary" to keep Spirit alive.

"This is really significant," Squyres added. Earlier projections had held that engineers would have to put Spirit into a very low-power mode to make it through winter and have the rover turn off heaters to conserve power, much like they did with Opportunity during the global dust storm in June-July 2007.

Even so, since the cold winter temperatures on Mars could easily trigger the survival heaters on the rover electronics module (REM), engineers took the extra precaution of disabling those particular heaters on Sol 1533 (April 25, 2008). It was insurance, really, that Spirit would conserve its power.

The survival heater for the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES), however, was not disabled. The team was bent on using the mineral-seeking instrument to search for more silica – a sign of past water – once the Martian winter was over. And just because Opportunity’s Mini-TES survived the cold and still works – though its optics are completely obscured with dust from the 2007 global storm – doesn’t necessarily mean the device on Spirit will be as hardy.

During the month of May, the rover held onto its modest but workable power levels. "It's dropping much more slowly than first anticipated and it's pretty stable," Matijevic confirmed.

As the weeks passed, Spirit, managed to squeeze in some research with the Mössbauer spectrometer, looking for iron-bearing minerals in a soil exposure named for Tuskegee Airman Arthur C. Harmon, and continued its routine atmospheric observations. But its main science task remained the picture taking for the Bonestell Pan. “We're a little more than half way done,” said Bell toward the end of May.

That same month, down on Earth, the MER team's paper on Spirit's discovery of near-pure silica around Home Plate two years before, in May 2006, hit the pages of Science. The journal report – "Detection of Silica-Rich Deposits on Mars" – cited evidence for the silica found in soils and in bedrock forming under hydrothermal conditions as "strong indicators of a former aqueous environment.” Hydrothermal environments on Earth are known to support thriving microbial ecosystems, and Squyres and his co-authors concluded this discovery is "important for understanding past habitability of Mars.”

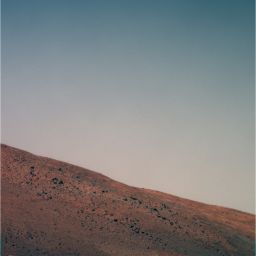

Spirit at Home

This image shows Spirit on the northern edge of Home Plate in the Columbia Hills of Gusev Crater. The picture was taken earlier this year just before winter solstice in Mars' southern hemisphere at about 2 p.m. local time on the rover's Sol 1591 (June 24, 2008). Home Plate is the elevated round and light toned mesa on the right side of the image. Spirit is visible at the large dark spot on the north-northeast edge of the circular volcanic formation. Mid-winter on Mars is the time of the clearest and least dusty atmosphere.

Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

During the Memorial Day weekend, while the Mars Exploration Rovers both forged onward slowly, heading into the depths of their third Martian winter, Phoenix assumed the Martian spotlight with its flawless touchdown in the north arctic region of the Red Planet. Beyond sending good luck wishes, the MER team bestowed the new mission with a generous and valuable gift, the services of renowned geologist and veteran Martian explorer Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis, who had overseen Spirit’s mission since landing and in decades past worked on Viking, the first two American landers on Mars.

Although Spirit’s power levels continued to drop as expected, dipping to levels just below 200 watt-hours, or about one-fifth the levels it had on landing, they didn’t drop as much as anticipated. Nevertheless, Spirit’s objective at least through the Martian winter solstice, June 25, 2008, remained the same: "Survival. Stay alive, that's it,” as Squyres put it.

By hunkering down and putting even its routine science agenda on hold for most of June, Spirit managed to cautiously cruise through its third Martian winter, even though it was experiencing temperatures that cycled from -20 to -30 degrees C (-4 to -22 degrees F) in the middle of the day to -110 Celsius (-166 Fahrenheit) at night. "Its current levels of about 230 watt-hours are better than we predicted," noted Matijevic in the sols after the winter solstice. "And we've basically gotten to the bottom of the energy curve, again."

Spirit’s future looked brighter than it had in months. Despite the ever-thickening coat of dust on its solar arrays, it was still taking in, remarkably, about 34% of the available sunlight for energy. The rover’s tilted position on the northern edge of Home Plate had enabled it to maximize intake and maintain power levels averaging around 225 watt-hours throughout July. So, the rover got right back into work, albeit slowly, tunnel-visioning its science efforts on taking pictures for the Bonestell Pan and keeping an eye on the dust overhead.

By August, Spirit was able to pick up the pace of its photography. The temperature was rising at Gusev Crater and thus decreasing the demand for survival heating.

In fact, the net survival heating for the rover's main batteries and its Mini-TES had decreased almost by half, taking only 50 watt-hours instead of the 80-to-90 watt-hours it was consuming leading up through winter solstice, according to Matijevic. The rover's power production, as a result, improved slightly to 235 watt-hours. "It's helped us free up some margin to do more science, so we've been starting to crank out a fair number of frames for the Bonestell Panorama this past month," confirmed Banerdt.

NASA, meanwhile, released the first half or south view of the Bonstell Panorma that month. It revealed the rover’s forward view of Home Plate in full Martian color, offering a good glimpse of what was to come.

Throughout September, Spirit kept its rover nose to the grindstone from its parked position on Home Plate, methodically snapping image after image, column after column of Pancam pictures for the grand panorama, as well as monitoring the dust in the atmosphere, and otherwise conserving power as winter slowly began to recede.

After months of working reduced hours in "winter ops,” the MER team returned in September to nominal planning for Spirit. In other words, Spirit got back to its regular daily work schedule and its team on Earth returned to uplinking commands three times each week, informed Laubach, who oversees mission managers, rover planners, and most of the people who sequence the commands that turn the scientists' objectives into the instructions sent to the rovers. As a result, the rover “picked up the rate of imaging for the Bonestell Pan,” she announced, “because of the increase in power.”

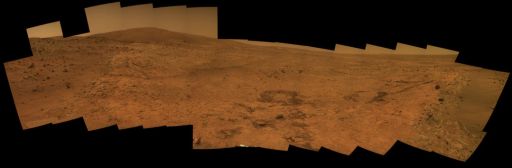

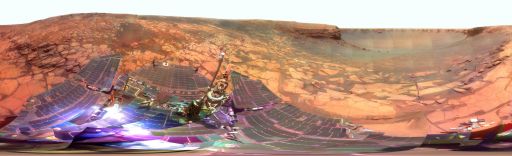

Bonestell Panorama, south view

Bonestell Panorama, south viewThis 180-degree panorama shows the southward vista from Home Plate North, where Spirit is spending its third Martian winter inside Mars' Gusev Crater. Home Plate, which is about 80 meters (260 ft) in diameter, is an eorded over volcanic formation. This view combines 168 different exposures that Spirit took with its panoramic Camera (Pancam) -- 42 pointings with 4 filters at each pointing. Spirit took the first of the images that are combined into this view on its Sol 1477 (Feb. 28, 2008), two weeks after the rover made its last move to reach the location where it would stop driving for the winter. Solar energy at Gusev Crater is so limited during the Martian southern hemisphere winter that Spirit does not generate enough electricity to drive, nor even enough to take many images per day. The last frame for this mosaic was taken on Sol 1599 (July 2, 2008). Spirit is to finish taking images for the northern half of the scene during the Martian spring. The northwestern edge of Home Plate is visible in the right foreground. The blockier, more sharply shadowed texture there is layered sandstone whose layering is tilted inward toward the edge of the Home Plate platform. A dark rock on top of Home Plate in that area is a porous volcanic basalt unlike rocks nearby. The northeastern edge of Home Plate is visible in the left foreground. Spirit first climbed onto Home Plate on that region, in early 2006.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

“We’re not driving obviously, but the other instruments can be active, so it makes sense for us to plan frequently enough to take advantage of all the power that we do have,” Squyres noted. “Everybody is kind of eager to get moving, but we have to wait for the power levels are high enough before we do it,” he added. It wouldn’t take long.

The Pancam team, however, had a valid interest in Spirit completing Bonestell before the rover moved, Bell confirmed. Otherwise, a lot of tedious adjustments would have to be made in “post-production” down on Earth. Toward the end of the month, the rover had managed to complete approximately 75% of the big panorama, although not all of that data had been downlinked. “We've got about 20 pointings left, so depending on power levels, downlink data volume levels, and other rover health issues, we might be able to finish this in perhaps two to three weeks,” Bell suggested.

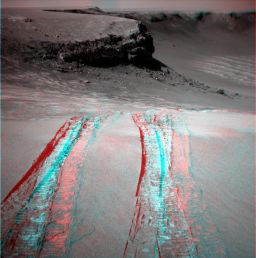

Spirit bumps upslope

Spirit bumps upslopeSpirit began its fourth season of motion on Mars with some short "bumps" up the northern slope of Home Plate. This animation is composed of four views taken from Sol 1707 (Oct. 21, 2008) to Sol 1713 (Oct. 27, 2008) with the forward Hazard Avoidance Cameras, mounted just below the solar panel deck in front of the rover.Credit: NASA / JPL / animation by Michael Howard

As the skies continued to brighten and the temperatures warmed at Gusev Crater, Spirit’s power production edged up to the 250 watt-hour threshold for which the team had been waiting since the Martian winter solstice. Finally, on Sol 1709 (October 23, 2008), the rover took the spotlight as it "bumped" a move.

The "bump" or short move was the first time Spirit had moved from its stationary position just off the northern edge of Home Plate in nearly eight months and it performed flawlessly. As the rover inched up the northern slope of Home Plate some 8 centimeters (3.1 inches) from its perch, it endeared the MER team and the hundreds of thousands of its human admirers around the world yet again. As rover driver Scott Maxwell has put it on numerous occasions: “How can you not love these rovers?”

In moving, Spirit changed the tilt of its solar arrays to a more productive 25-degree angle, a better position to take in the energy from the spring Sun. "I felt real good about seeing the wheels turn and about actually making uphill progress when we were on a 30-degree slope," Squyres said. If the rover could climb back on top of the circular formation, then it could take a more direct route to its next major destinations, Goddard and von Braun, to the south. "We were successful in moving uphill,” Squyres acknowledged, “but I'm not yet prepared to say that we're going to make it up onto Home Plate.”

A couple weeks later, in early November, Spirit’s outlook changed when it took a direct hit from one of Mars’ notorious dust storms. The MER team had gotten advance notice through a weather report from the MARCI crew on MRO and scrambled to uplink power-conserving instructions, commanding the rover to cut its energy demands to the titanium bone in an effort to avoid draining the main batteries. The rover was told to hold off on communicating for a few days and to pull the plug on the heater for the Mini-TES, which the MER team had worked so hard to keep online.

“This was a very serious storm and it was real scary,” Squyres admitted. “We were not able to predict how bad the conditions would be. We had to assume the worst, but, the thing is, we didn't know was how much dust was in the atmosphere or how much dust was on the solar arrays.”

Despite the heroic attempt by the engineers on November 8, the rover's next electronic communiqué, received November 10, revealed that the dust in the atmosphere – combined with the dust on the rover’s solar panels – caused Spirit’s power levels to plunge November 9 to an all all-time mission low of 89 watt-hours.

Such storms had sideswiped Spirit before, particularly during the global storm of 2007, but this one “just hit head on and the power plummeted,” Squyres said.

Since they had instructed the rover not to communicate until Thursday, November 13, the team had no way of knowing if Spirit would follow the conservation commands or if it was too weak to do anything. If Spirit shut down because of low power and drained its main power batteries, it might not wake up.

Dust storms come with the onset of spring in Mars’ southern hemisphere, so his storm was not exactly unexpected. But coming as it did, right after the rover had come out of winter, took an emotional toll on the team, Laubach said. But, seemingly fearless and dedicated beyond definition, Spirit lived up to its name, phoning home November 13, 2008, at 11 a.m. Pacific Standard Time, exactly like the MER team had asked it to do, boasting a conserved power level of 189 watt-hours.

Somehow, Spirit had not gone into an automatic low-power fault mode. "That was a shock to us," Laubach said. "Most of us thought that Spirit would have gone into her low power fault mode by the time we heard from her, because she certainly could not sustain that extremely-low power generation for long without draining her batteries."

Silica

SilicaSpirit shot this false color image looking toward Silica Valley, aka East Valley, on Sol 1213 (June 2, 2007) with its Pancam. The false color enhances some of the silica-rich soils the rover had been studying in the little Valley between Home Plate and Mitcheltree Ridge. The scientists on the MER team hope to be able to use the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) to find more silica in 2009.

Credit: NASA /JPL-Caltech / Cornell

The team at JPL cheered and celebrated with brownies and hugs. “It was a good day on Mars today,” said an obviously relieved Squyres, during an interview late that afternoon from the rovers’ mission control.

The hope had been that some gust within the Martian winds would blow off a bit of the dusty layer on the rover’s solar array, but Mars added insult to injury. “The storm blew more dust on her," informed Laubach.

The Mini-TES though kept on ticking. Truth told, team members thought maybe Mini-TES would survive based on the fact that Opportunity's Mini-TES has survived for years now in DeepSleep modes where its heaters are shut off along with everything else. But it was certainly nice to know for sure. "The Mini-TES instruments are turning out to be very robust to this kind of thermal cycling and very low temperatures," said Steve Ruff, of Arizona State University, the acting lead scientist for the instrument for Spirit.

The dust storm, however, was without doubt “a real close call” for Spirit. “We’re pleased we got through the dust storm,” said JPL's Callas. “That was dodging a bullet.”

From the storm, Spirit went into solar conjunction with a simple, autopilot objective, one it came to know pretty well in 2008 – conserve power and stay alive. It achieved that objective, and emerged producing 169 watt-hours of energy when operations returned to normal in mid-December. That is really low, as rover power levels go. But it’s enough power to allow Spirit to survive and keep on roving, at least for now.

During the final two weeks of 2008, Spirit attempted two more times to get up on top of Home Plate. But that was not to be. “We tried to do 10 or 12 meters of straight uphill driving and we slipped cross slope about 65 centimeters (about 25.5 inches) and down slope about 8 (about 3.1 inches) centimeters,” said Squyres. “This is Mars’ way of telling you you’re not going to get there from here.”

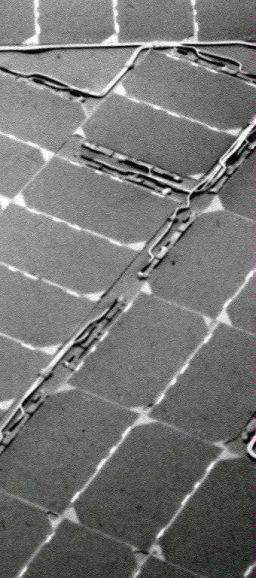

Dusty arrays

Dusty arraysSpirit took this image of its solar panels with its Pancam last October. The arrays are so coated in Martian dust they look like sandpaper. And, even though the rover "bumped" to better angle itself toward the Sun, the dust in the skies overhead fluctuated up and the power-challenged Spirit lost a little energy in October. Then, it got pummeled by a local Martian dust storm. It wasn't enough, however, to stop this rover.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

It was clear then that Spirit would have to back down off Home Plate and rove partway around the plateau into order to head to its next, long-awaited destinations located about 183 meters (200 yards) on down the road – an odd coupling of a house-size pit in the ground and nearby mound above ground – named, respectively, for American rocket pioneer Robert Goddard and his German counterpart Werner von Braun.

While von Braun might yield support for the finding that Home Plate is a remnant of a once more-extensive sheet of explosive volcanic material, a light-toned ring around the inside of Goddard may add to information about a nearby patch of bright, silica-rich soil that Squyres ranks as Spirit's most important discovery on the mission to date. The silica, the MER science suggests, was likely produced in an environment of hot springs or steam vents.

Goddard looks different, Squyres said. It “doesn't look like an impact crater. We suspect it might be a volcanic explosion crater, and that's something we haven't seen before."

The good part about Spirit’s new route to Goddard and von Braun is that the rover will get the tilt needed to get to a more comfortable power level quickly. “The main thing is the Sun is moving away from us now, moving away from our high tilt,” Squyres said earlier this week. “We want to be at a tilt of more like 12 or 14 degrees right now.” The downside to the new route, of course, is that Spirit will now have to go partway around Home Plate in order to head south, instead of taking a straighter shot across the top, making for what could be a lot longer journey. “That’s life,” said Squyres.

The hope remains that Spirit will experience a dust-cleaning event soon, but that isn’t necessarily likely even though this is the season for winds on Mars. “We’re in a geometry, a region where we’re not expecting the kinds of cleaning events we got when we were climbing the Columbia Hills two Martian years ago, so we’ll take what we can get,” said Callas. “It’s going to be tough going for Spirit. But the vehicle is still quite capable.”

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

As 2007 gave way to 2008 at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity was in the midst of its investigation of the tri-layered rock ring that circles the interior of Victoria Crater. The team had named the three layers for famous stratigraphers – renowned Danish physician-anatomist-geologist Nicholas Steno (1638-1686), who first described the organic origin of fossils and fundamental principles of stratigraphy; British geologist William Smith (1769-1839), the first scientist to apply the principles of stratigraphy on a large scale in the 1790s and early 1800s; and Sir Charles Lyell (1797-1875), the Scottish lawyer who became the leading geologist of his day, and an influence on a young Charles Darwin. The rover had worked its way down about 15 meters below the rim to the third layer, dubbed Lyell, as the New Year rang in. "We're on steep slopes, but the drives have been fine," said Jake Matijevic, of JPL, chief of the MER engineering team.

In February, Opportunity was still conducting its close-up examination of Lyell, homing in on its fourth target there, Buckland. Once it had completed that work, though, the rover descended approximately 6 more meters (about 19.7 feet) further down the slope toward a layer the team named in honor of American stratigrapher-geomorphologist-structural geologist-cartographer Grove Karl Gilbert (1843-1918).

Although this part of the crater slope features "very sandy" terrain strewn with the tiny spherules known as "blueberries" and Opportunity had trouble negotiating it, the rover and its drivers persevered. During the month of March, the rover managed to conduct a steady amount of science from a solitary position, maneuvering its arm in and out of position to finish the close-up examinations of targets in the Gilbert layer.

Opportunity then powered up and took off for the base of Cape Verde, driving 5.5 meters (18 feet) on Sol 1484 (March 27, 2008) and another 5 meters (16.4 feet) or so on Sol 1486 (March 30, 2008). Amidst its swift progress, the rover became snared in a nasty little sandpit, so small it had escaped its view.

Once engineers on Earth had analyzed the situation, Opportunity began its pullback and put four of its six wheels back on the bedrock path from which it came before calling it a sol on April 14. But when it went to unstow its arm, as had been standard operating procedure for a couple of years because of an “arthritic” shoulder joint, the arm stalled in the first movement, just as the rover was swinging its shoulder out to the side. The robotic arthritis suddenly brought the rover to a standstill.

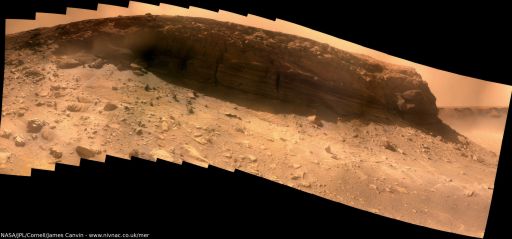

Lyell Panorama

Lyell PanoramaFor four months prior to the fourth anniversary of its landing on Mars, Opportunity examined rocks inside an alcove called Duck Bay on the western portion of Victoria Crater. The main body of the crater appears in the upper right of this panorama, with the far side of the crater lying about 800 meters (half a mile) away. Bracketing that part of the view are two promontories on the crater's rim at either side of Duck Bay. They are Cape Verde, about 6 meters (20 feet) tall, on the left, and Cabo Frio, about 15 meters (50 feet) tall, on the right. The rest of the image, other than sky and portions of the rover, is ground within Duck Bay. The rover's targets of study during the last several months are the rock layers within a band exposed around the interior of the crater, about 6 meters (20 feet) from the rim. Bright rocks within the band are visible in the foreground of the panorama. The rover science team named the three subdivisions of the band Steno, Smith, and Lyell, after legendary geologists. This view combines many images Opportunity took with its Pancam from Sols 1332 through 1379 (Oct. 23 to Dec. 11, 2007). Images taken through Pancam filters centered on wavelengths of 753 nanometers, 535 nanometers and 432 nanometers were mixed to produce this view, which is presented in a false-color stretch to bring out subtle color differences in the scene. Some visible patterns in dark and light tones are the result of combining frames that were affected by dust on the front sapphire window of the rover's camera. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Although Opportunity’s shoulder joint had been stalling occasionally for more than two years, the engineering team had designed a workaround that basically involved the rover applying increased voltage to overcome the problem and it had worked just fine. But most of the time, the stall happened when the rover was making tiny little motions. "This event was different," said Squyres. “This time it happened during an unstow event. We've never seen that before."

The engineers, not surprisingly, quickly zeroed in on the small motor that controls the azimuth or sideways motion – Joint 1 – and went to work figuring out if they could ever rely on it again and if not how the rover could keep on roving and make use of an arm it could no longer stow. The prognosis for Opportunity's shoulder was “not particularly encouraging," but the engineers "can develop a different operational regime," assured Matijevic. A broken steering wheel hadn’t been able to stop Spirit, and no one at this point could believe a frozen shoulder would stop Opportunity.

Opportunity deploys robotic arm

Opportunity deploys robotic armDuring its Sols 1531and 1532 (May 14-15, 2008), Opportunity successfully deployed its stuck robotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD) with a little help from its friendly ground crew.Credit: NASA / JPL / animation by Emily Lakdawalla

May literally blew in for Opportunity as Mars whipped up a series of santanas that cleared some dust from its solar arrays. With an increase in the amount of sunlight fuel it could access, the robot field geologist's energy levels rose to an average of around 420 watt-hours. Throughout most of that month, however, the rover, like an injured athlete sidelined but raring to go, was stuck in its tracks on the way to the base of Cape Verde awaiting diagnosis and treatment.

Since it couldn’t drive, Opportunity spent quality time conducting remote sensing and atmospheric research. It took measurements of argon gas in the Martian atmosphere with its alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), snapped some time-lapse movie frames in search of clouds with its navigation camera, and began taking some of the hundreds of Pancam images that would become the Garrels Panorama.

Named for Robert Minard Garrels (1916-1988), an American geochemist who applied experimental physical chemistry data and techniques to geology and geochemical problems, this panorama would present a sweeping view of Cape Verde and the slope where the rover was to exit Victoria Carter. Because of the global dust storm of 2007, the rover was shooting the Garrels Pan with a new technique.

"During the dust storm we accumulated some dust on the Pancam optics, so one side of the camera frame is dirty and one is kind of clean. Because we have the time to do it, we're taking half-frames, then overlapping those – obviously using the clean side – so we'll get a prettier panorama that way," Squyres explained. As May progressed, Opportunity “more than finished” the Garrels Panorama, he said, and continued with other science experiments.

Amidst that work – after engineers and scientists tested all the possibilities on the lab rover in JPL’s Mars Yard – Opportunity on Sol 1531 (May 14, 2008) finally moved its shoulder joint and opened its robotic arm, positioning it to the front. “It moved fine,” said Squyres. That alone was pretty amazing, really, considering the rover had survived more than four Earth years, and almost three Martian winters, a major dust storm, and more than 1,500 day-to-night temperature cycles on the Red Planet.

Opportunity’s drivers spent the rest of the month making sure their charge could actually drive with its arm out front or partially unstowed. As it turned out, it wasn’t the first time the rover had attempted to drive like that. "We did some minimal driving back about two years ago when we had our first problem with the shoulder joint, when we on our way over to Victoria Crater,” Matijevic informed. On Sol 1547 (May 31, 2008), Opportunity roved on for the first time in six weeks. At least it made the first move to extricate itself from the little sandpit that it had blindly run into the month before. The rover was commanded to drive out “straight backwards,” one or two meters, Squyres said – and it succeeded in moving a few centimeters.

Sporting energy levels up around 450 watt-hours, Opportunity bounded into June. With its arm unstowed and held out front in what the team dubbed the ‘fisher’ position, the rover, seemingly proudly, took three more drives to back out of the tenacious little sandpit. Then, it zigzagged in toward the base of Cape Verde, marking the winter solstice milestone on June 25 by roving on. "We're delighted," said Squyres. "It was looking kind of grim with that arm for a while.”

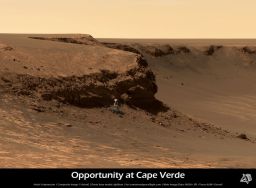

Cape Verde Panorama

Cape Verde PanoramaOpportunity captured this breathtaking view of Cape Verde during a weeklong pause in its crawl toward the cliff earlier this year. It is shown here at only half its full resolution; visit James Canvin's website for the full-resolution view.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / James Canvin

At about 8 to 10 meters (25-30 feet) from the base of Cape Verde, the team found Opportunity in “a beautiful position” for “taking a Pancam panorama for the ages of Cape Verde," as Squyres put it. The rover rose to the honor, sending home "spectacular" images from its Pancam, the likes of which the mission team had not seen before.

As Opportunity moved in toward the cliff base, the shadowed area near the cliff and the 12-degree adverse tilt toward the south caused its power levels to drop from 450 watt-hours to around 370 watt-hours. Even so, the plan was to get to one last target on the slope. But after slipping and sliding and not getting to that target, something happened that changed that plan. The rover experienced a spike in the electrical current to the motor for its left front wheel, an event ominously similar to what Spirit experienced just before it lost the use of its right front wheel for good back in March 2006.

During a subsequent series of diagnostic tests, the wheel maneuvered perfectly. "It seems to have been only a transient event," said Matijevic. That noted, the team had always been concerned that if this rover lost use of one of its wheels inside the crater, it would never be able to get out. “The slopes are just too steep for us to climb out at the same time we're trying to drag one of the wheels like we do with Spirit," the rovers’ chief engineer pointed out.

The MER team decided then it was time for Opportunity to bid adieu to Victoria Crater. It would exit the same way it entered, by way of the shallow slope at Duck Bay, "basically following the path it took to come over the rim and down the crater wall when it entered about a year ago," said Matijevic.

Still, “out of the crater,” as Callas noted then, was “up from where we are right now." The rover took the first drive to that end on the last day of July, Opportunity’s Sol 1607, moving 24 centimeters (about 9.4 inches) and making a 5-degree heading change despite significant slippage of around 90%.

During the next few weeks, Opportunity charted course back to Duck Bay. Roving now with its robotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD) partially opened and positioned out front, the rover proudly proved it has the poise, stability, and balance of an Olympic gymnast. "The arm did not move," Matijevic said. It was slow, slippery going at first, but once Opportunity managed to take leave of the slope and get back onto its previous tracks and a rockier road, it made swift progress.

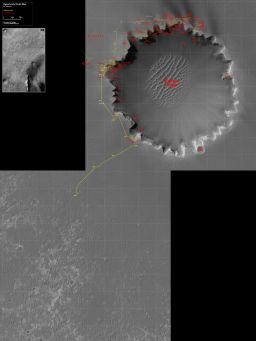

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapBy Sol 1691 (Oct. 25, 2008) Opportunity was more than 400 meters to the southwest of Victoria crater, which it departed on Sol 1682 (Oct. 16, 2008). The rover was headed for an area where the north-south dunes of Meridiani Planum are spread thinly over exposed bedrock, a landscape that provided the rover with a "highway" southward on its journey toward Endeavour Crater. The inset to the upper left shows the land between Victoria and Endeavour. Grid lines are spaced 100 meters apart.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / Eduardo Tesheiner

After driving a total of some of 50 meters (about 164 feet) to get back to Duck Bay, on August 28, 2008, Opportunity roved for 6.8 meters (22 feet) up and over the top of the inner crater slope, through a sand ripple at the lip of Victoria, and back onto the plains, crossing another mission milestone on the way. "The rover is back on flat ground," engineer Paolo Bellutta, one of the rover drivers at JPL, announced early Friday to the mission's international team of scientists and engineers as the confirmation arrived on Earth.

"We'd done everything we entered Victoria Crater to do and more," said JPL's Bruce Banerdt, MER project scientist. "Our main objective going into the crater was to, in effect, repeat the chemical stratigraphy that we did at Endurance Crater and compare the two to see if there are correlations between the profiles of the chemistry as the rover went down through the layers and back in time through the geology."

Opportunity spent a few Martian sols investigating the three sets of tracks it's made at Duck Bay over the last couple of years, then roved back toward the crater to check out a classic Martian ripple at the rim. There, it also “practiced new techniques” for how to reach its instrument deployment device (IDD) targets, said Laubach. The rover then headed toward an area the team named in honor of desert explorer Ralph Alger Bagnold.

“It looked like the cleanest patch of Meridiani dust that we’ve seen anywhere,” said Squyres. And the MER science team was anxious to determine its composition with its mineral detecting instruments. Opportunity slipped repeatedly trying to scale the ridge leading to the chosen target within Bagnold, Laubach said, so the MER team was forced to abandon that target and instead instructed the rover to move on. “We did our best to get to Bagnold, but it became clear after a few sols that we were just wasting our time,” Squyres said. “We could try for months and never get to it, so it was time to go.”

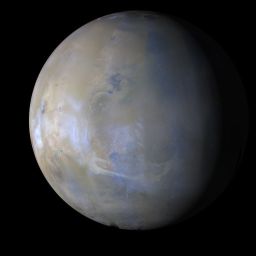

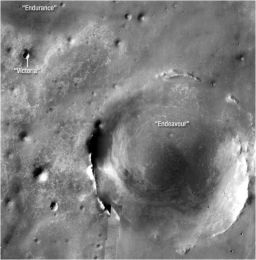

Opportunity's next big destination

Opportunity's next big destinationThe MER team has chosen a a crater more than 20 times wider than Victoria Crater as Opportunity's next destination. The rover began the long, 12-kilometer (about 7.5-mile) journey -- which p.i. Steve Squyres estimates will take about 2 years, with science stops along the way -- on Friday, Sep. 26, 2008 with a 152-meter drive. The crater, which is to the southeast of Opportunity's location at Victoria, dominates this orbital view from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) camera onbaord Mars Odyssey orbiter. Victoria is the most prominent circle near the upper left corner of the image. This view is a mosaic of about 50 separate visible-light images taken by THEMIS.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASU

On September 22, NASA and the MER team announced exactly where Opportunity would go next – a giant crater to the southeast – 22-kilometers (13.7-miles) in diameter and 300 meters (984 feet) deep. More than 20 times larger than Victoria Crater, this new mammoth crater – which the MER team provisionally named Endeavour – is “staggeringly large compared to anything we've seen before," as Squyres put it.

As MER objectives go, it was "bolder, more aggressive” than any before it, added Callas.

It’s an ambitious destination to be sure. Endeavour lies 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) from Victoria. That is the total distance Opportunity had driven in the four years and almost nine months it had been on Mars. In fact, it just crossed that 12-kilometer milestone.

"We keep setting the bar higher for what these rovers can do," said Frank Hartman, a JPL rover driver. "Once it seemed like a crazy idea to go to Endeavour, but now we're doing it."

Endeavour is the largest formation or object that the MER team has targeted for either rover and it is the first moniker of a rover destination that the team has officially suggested to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), which officiates over the naming of landmarks on other planets.

Blessed by a series of Martian gust that continued to clear some of the accumulated dust on its solar arrays, Opportunity was amped, its power levels shooting up past 650 watt-hours in September. Neither rover nor drive team would hold back.

On September 26, Opporutnity put the pedal to the metal and logged an impressive 152 meters (about 498 feet) on its odometer, according to Squyres. Actually, it was kind of taking it easy because it still had some work to do to complete its picture of Victoria. “It's roving not too far from the rim, driving counterclockwise around the crater in the other direction from 2005 tour,” said Laubach.

Opportunity spent most of October bidding a final farewell to the hole in the ground that had been its home for the past two Earth years. From Duck Bay, it roved around the crater to the south, past Cape Pelar to the north end of Cape Victory in order to take some Pancam pictures of Cape Pelar. It then roved on to the next promontory to the south, to turn back and image Cape Victory.

A parting shot

A parting shotFrom the crater rim, Opportunity gave a final salute to Victoria Crater, raising its robotic arm on its Sol 1639 (Sep.2, 2008) and taking a snapshot of its shadow with the front hazard-avoidance cameras. The rover completed the salute by swinging the arm at its elbow joint back to the starting position.Credit: NASA / JPL

Then, on Sol 1682 (October 16, 2008), it really “hit the gas,” as Squyres put it, leaving Victoria for good. The rover was "ripping," he said, logging a breathtaking 216-meter (709-foot) drive that fell short of the mission’s all-time record “by just 4 meters.”

Opportunity made its longest drive of 220 meters (about 722 feet) way back in 2005 on Sol 410, "a little ways south of Endurance and toward Victoria," recalled Squyres. "But that was a long time ago and the terrain there was much easier than the terrain we're driving in now."

Since Endeavour is so far away, Opportunity’s mission turned from one of crater investigation to one that is all about driving and the driving was good. Although the Meridiani highway is paved with ripples as well as bedrock patches, most of the ripples in the region south of Victoria are of moderate size, standing about 10 centimeters (about 4 inches) tall.

Using orbital images taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera, they spotted larger ripples, however, ripples or mounds more in the range of 35 centimeters (almost 14 inches), more like the size of Purgatory Dune, which trapped Opportunity back in April 2005 and held it prisoner for six weeks.

The larger ripples are so reminiscent of Purgatory Dune – and that experience was so frighteningly memorable – the MER team, revealing its life-preserving sense of humor, decided to pay homage. "We're starting to see some purgatoids,” said Squyres in October, “and we're being real careful to avoid those."

Opportunity’s objective for November was to get to an intermediate destination of extensive outcrop of layered rock – which the team also saw in the HiRISE high-resolution images – before solar conjunction. "We nailed it," said Squyres, who is also a member of the HiRISE team. Since leaving Victoria Crater in mid-October, the rover had logged 1,253 meters or 1.25 kilometers (0.77 mile) in six fast weeks.

On its arrival at the patch of outcrop, Opportunity followed its accomplishment with another achievement – roving right up to a cobble where it would spend the two-week communications blackout of solar conjunction. They had been looking for “a good size cobble” to study during for conjunction. “We drove and drove and weren't seeing any cobbles. Then, right when we needed one – boom – there's Santorini, right there in front of us," Squyres marveled.

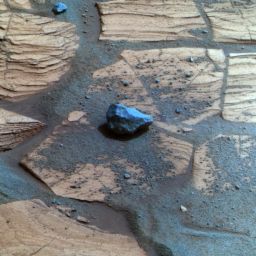

Santorini

SantoriniOpportunity used its panoramic camera (Pancam) to take this false color image of Santorini, the cobble it studied up close through solar junction. The rover snapped the picture on its Sol 1713 (Nov. 17, 2008), the same day it nudged up to it and puts its instrument deployment device (IDD) on its surface.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

The rock was named after the small archipelago of volcanic islands in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 kilometers southeast from Greece’s mainland. “These cobbles are like little islands out in the sea, and I figure we’re going to see a lot of cobbles and there are a lot of islands,” explained Squyres of the new naming theme.

Santorini’s composition became the prime directive and as this rover’s unbelievable luck would have it, Opportunity managed to place the Mössbauer spectrometer on it with the first try. Once the contact switches on the instrument confirmed that the spectrometer had touched the surface, the German-made spectrometer was turned on and the analysis of the cobble’s iron content got underway. "This is the first time we’ve tried to do in situ measurements on a cobble since the shoulder azimuth joint was disabled," Laubach pointed out. “We had done IDD measurements on that ripple at Duck Bay, but that was a nice broad target. This was the first time where we had a very specific target we wanted to hit and the team did the placement on the first attempt."

Throughout 2008, Opportunity continued its routine of regularly going into DeepSleep, a mode where it shuts down systems, turning everything, including heaters, off for the night. It began this routine not long after landing in January 2004 when engineers discovered that one of the heaters in its warm electronics box was stuck in the ”on” position and draining precious energy. So far, somehow, the rover doesn’t seem much worse for the wear of the Martian cold. “Things are pretty good at Meridiani Planum these days,” Squyres summed up.

As Opportunity returned to its normal schedule following solar conjunction, it continued its close-up investigation of Santorini taking measurements with its alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) and some close-up pictures with its Micrcoscopic Imager (MI). The cobble, Squyres announced this week, turns out to be another meteorite, a type of stony iron meteorite called a mesosiderite, basically “a dead ringer” for Santa Catarina and Barberton. “You don’t see this type of meteorite very often on Earth, but of the four meteorites we’ve found at Meridiani Planum, three are like this,” Squyres pointed out. “They are so similar to one another that we suspect they may be pieces of the same thing.”

The name "mesosiderite" comes from the Greek mesos for "middle" or "half," and sideros for "iron" and reflects the fact that these meteorites are roughly equal mixture of differentiated silicates and iron-nickel. Mesosiderites are thought to have formed through the action of catastrophic impact events that mix the surface of the parental body with the nickel-iron core material.

In the final weeks of December, Opportunity has checked out a rock and soil sample, as part of what is to become a systematic sampling of the chemistry and bedrock of the terrain. “It’s something we’ve decided we should do every so often – like every kilometer or two as we work our way south – to see if there are any trends,” said Squyres. “So we finished with Santorini, did a little bump forward to get into position to where we could take some measurements of rock and soil and we’re making APXS measurements and MI imaging there.” Once that task is finished, Opportunity will rove on, he said, “and we’ll start driving fast again.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth