Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 04, 2007

The Space Age turns 50

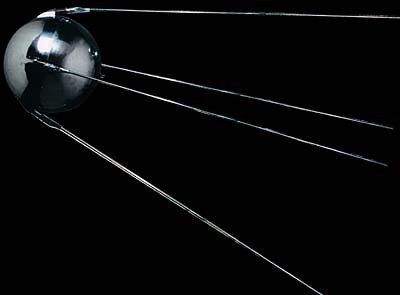

Around the world, there is conversation today about the fiftieth anniversary of the launch of Спутник, that is, Sputnik, Earth's first unnatural satellite. When Sputnik was tracked across American skies it inspired fear and paranoia in some, wonder and curiosity in others. It was the fear and paranoia that led the American government to commit the resources necessary to land men on the Moon within a dozen years, but it was the wonder, curiosity, and thrill of the challenge that drove -- and continue to drive -- the men and women who built and operated spacecraft, launching them from points across the globe to orbits across the solar system.

There is no doubting the significance of Sputnik in launching the Space Age. In media outlets around the world, people are speaking about how Sputnik changed everything, leading to amazing achievements in technology and exploration. There is a lot of talk, too, about the failure to deliver on the promises of the dawn of the Space Age: there are no moon bases, and no humans have ever been to Mars; here on Earth there are no jet packs or antigravity boots.

I'm impatient with such talk. Sure, there are no moon bases, and that's a bummer if you believed, as you watched the Apollo landings on TV, that you would get to go someday. But we're not too good at predicting the future in any industry, and I think that it's silly to feel regret about the failure to achieve some of the starry-eyed prognostications of the past. There's no manned mission on the Moon right now, but there are twenty -- twenty!! -- robotic spacecraft currently active on missions to explore other worlds in solar system, going places no human may ever go.

Just think about what these spacecraft are doing, have done, or are about to do. Five of them are currently exploring Mars: Mars Odyssey, Mars Express, Spirit, Opportunity, and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and a sixth, Phoenix, is on the way. Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are pushing the outer boundaries of the solar system, way beyond the orbit of Pluto. Also far out are Cassini, just reaching the midpoint of its currently planned exploration of the Saturn system, and New Horizons, on its way to the Kuiper belt. Looking inward, Venus Express is watching the skies of our sister planet, and MESSENGER is on its way to map Mercury, including the hemisphere that's never been seen up close. A crowd of spacecraft is studying the smaller bits of rocks, ice, and dust that make up the solar system between the planets; Rosetta and Dawn are on their way to comets and asteroids, Stardust and Deep Impact are embarking on extended-life missions, Hayabusa is struggling home, maybe with asteroid samples, and Genesis is awaiting further orders. Finally, Kaguya is ushering in a new age of lunar exploration, having just entered orbit today. No, we don't have our moon base, but we have a fleet of robots millions and even billions of kilometers from Earth, exploring places too dangerous or inclement for human explorers. I, for one, don't feel that the Space Age has failed to deliver on its promises.

It would be hazardous, though, if satisfaction led to complacency. As humans -- and human-made institutions -- age beyond 50, it's natural for them to become more conservative in their outlook, preserving their successes, continuing to do things in the ways that have served them well in the past, and not taking any great risks. I think that attitude shows in the current plans for the future of human exploration. It also shows in the trepidation with which we approach future plans for robotic exploration. Some new enabling technologies are now coming of age, like the ion propulsion system that is operating on Hayabusa and just launched with Dawn, and a few people are still willing to take great risks exploring the unknown, as seen with the Huygens landing on the terra incognita of Titan. But other technologies and goals look stalled in the laboratory, deemed too risky for selection for future missions, things like balloons for Titan, Venus, and Mars, and electronics that can survive the extremes of pressure and temperatures found in the atmospheres of the giant planets and on the surface of Venus. The Voyagers ushered in an age of exploration of the outer solar system, and Galileo, Cassini, and New Horizons got off the ground; but when will there be dedicated missions to Uranus or Neptune? When are we going to dive into the oceans of Europa or sludgy seas of Titan? When are we going to pick up a piece of Mars and bring it back to Earth?

We've got to keep pushing to turn our dreams into reality. Like antigravity boots and lunar vacations, some -- probably most -- of these dreams will not come true in our lifetimes, if ever; but to achieve success by lowering expectations is to encourage cynicism and disappointment. Don't let this anniversary be just a reminiscence of glory days past -- let's mark it and move on!

There are lots of great places on the Web to read what other people think about the significance of the anniversary of Sputnik's launch. One of the best is on the New York Times. Other places you can check are Wired, James Oberg's site, and the Economist.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth