Emily Lakdawalla • Nov 16, 2012

Dawn Vesta Data is publicly available (for real this time!)

Way back in January I wrote a blog post celebrating the release of Dawn data. Unfortunately, my celebration was premature; the data had not been authorized for release, and it was taken down from UCLA's website shortly after. It took me a while to find out what was going on that was holding up the release of the data. It came down to a dispute about the choice of coordinate system, a dispute that was a small part of a larger conflict over who should have the right to dictate names and coordinate systems. I'll let Eric Hand fill you in on the details.

Anyway, the dispute has been resolved, and data were provided to the Planetary Data System on November 9. This first release covers the Approach, Survey, and High-Altitude Mapping Orbit phases of the mission, including May 4 through November 2, 2011. You can browse or download it here.

It is a lot of data -- 36 GB, if you download the single .tar file. I tried that and the file was corrupt (not sure if it was my problem or theirs); so I used wget and got the versions of the data that I needed.

It's been a long time since I approached a new data set for the first time. It can be really hard, when confronting a folder tree containing 11,000 files, to know where to start. I've got my own method for exploring new data sets that I don't think anyone else I know uses: I build web pages displaying all the thumbnails and a selection of the metadata describing each image. It helps me understand not only what kinds of images were taken but also get some insight into why they were taken.

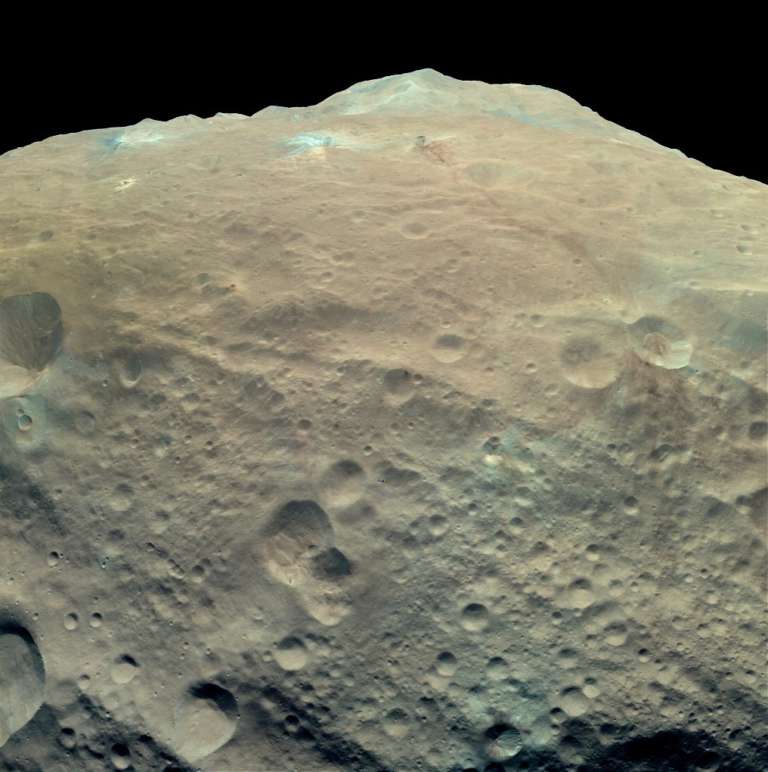

I haven't finished building pages for the entire data release yet, but I have finished the Approach and the Survey phases. You see Vesta turning from a dot into a world. A lumpy world, and a colorful one, too. Most asteroids are pretty monochromatic, a faintly reddish gray with maybe a couple of lighter-colored spots where there have been more recent impacts. Vesta is grayish and reddish and greenish with wisps of reddish stuff and crater splats of both bright and dark material, often in the same crater. Here's a global view processed from the newly released data by Daniel Macháček.

You may notice that this view is truncated on one side. This is one of my biggest frustrations about the data set: in all the 11,000 images, there is not a set that you can use to compose a global view that is not truncated somewhere. At least during these phases of the mission, the imaging team did not deem it a priority to create a portrait of their target world suitable for printing as a poster. Hopefully they included such a sequence in their plans before they departed.

Even if they didn't, there is hope for a color global view, but it will be really hard work. You can make a global view of a world by taking lots of images of pieces of the world and correcting the geometry of the view for the spacecraft's position, assembling numerous images onto a flat map that you can then "reproject" into the shape of the original world. This works really, really well when the world you're dealing with is spherical or some other mathematically (relatively) simple shape like an ellipsoid. But Vesta ain't no ellipsoid. It's the lumpiest, bumpiest, extremest-topography big world in the solar system. In order to generate a simulated global view, you first have to build a 3D model of this lumpy, bumpy world so you can understand the geometry of the images, skin the planet, assemble all the bits and pieces, and stuff the planet back inside your newly assembled skin. It's like planetary taxidermy.

Now, I know that the imaging team has, in fact, created a 3D model. A goodly proportion of the data taken during the survey phase of the mission was intended for just that purpose. They watched Vesta rotate underneath them, to explore the way its limb and its shadows changed shape. Here's a little animation of one part of one of those observations:

We've seen the 3D model in animations published by the mission. But that model is a work in progress. As what's called a higher-level data product, it's not going to be released any time soon.

Until then -- or until some amateur image processor goes through the trouble of making their own 3D shape model -- we'll have to settle for partial views of this world. But those partial views are very pretty. Included in this data release are numerous surveys covering the whole body in visible and infrared wavelengths. Here's one example view, sighting across south polar terrain to the peak of the Rheasilvia basin. Marching from the right foreground toward that mountain is a strange reddish wisp, an enigmatic feature unique to Vesta. What is it? It doesn't look like crater ejecta, though a crater seems to have smashed into some of it. If it wasn't caused by cratering, what else could it have been? The only other process likely to have operated on Vesta -- that we know of -- is possible ancient volcanism. Is this an exposed dike or something? Whatever it is, it's going to be hard to figure it out. But fun. Scientists don't do science because they expect it to be easy!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth