A.J.S. Rayl • Nov 30, 2008

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Recuperates from Dust Storm, Opportunity Hits on Santorini

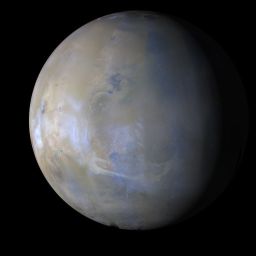

The Mars Exploration Rovers are nearing the end of their fifth year of exploring the Red Planet in dramatically different ways.

At Gusev Crater, Spirit is hunkered down and fighting for its life after a dust storm darkened its doorstep in mid-November, causing its power levels to drop to a life-threatening, record low.

On the other side of the planet, Opportunity seemed to be pushing the limits of robot life, bursting with energy as it cruised the plains of Meridiani Planum. When it roved onto a spread of bedrock and to a pitstop on its long journey to Endeavour Crater, it stopped right at a much hoped-for cobble, some 1.25 kilometers (0.77 miles) from Victoria Crater.

Spirit -- while still in its parked position on the northern edge of Home Plate, the circular volcanic formation where it hunkered down to survive its third Martian winter -- ultimately took “a direct hit” from a fierce and sudden local dust storm, according to Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, the principal investigator for rover science. It was a storm they knew about, however, in advance.

Mars exploration has advanced so significantly since the rovers landed on the Red Planet in January 2004 that the MER team can now acquire rather sophisticated images of terrain and weather reports from instruments on orbit to direct Spirit and Opportunity. On November 8, the scientists working with the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) alerted Spirit's ground crew that thick, swirling dust clouds were advancing from the west and would likely descend on the rover.

Engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were designed, built and are being managed, responded promptly to the forewarning. A team came in over the weekend and uplinked instructions for Spirit to conserve energy.

The rover's next communiqué, sent down on November 10, revealed that its power levels had hit all all-time mission low of 89 watt-hours. So, in the next plan uplinked, the MER team cut Spirit's power demands to the bone, and even commanded it to disable the heater for its miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES), which the team tried so hard and so effectively throughout the Martian winter to keep online. They had no way of knowing if Spirit was following instructions or too weak to do anything. After four days of silence, they got their answer. Spirit phoned home right on schedule on November 13, just like the crew asked.

The team cheered when they heard the news. Spirit was alive, listening, and talking. Once again, Spirit – and the MER mission – were back in the spotlight and daily headlines – even if some reporters got the rover mixed up with the Phoenix lander that did pass away in November as the Sun fell below the north pole horizon.

Dust storm hits Spirit

Dust storm hits SpiritA fierce regional dust storm descended on Spirit this month. It can be seen in the lower, left-to-middle section of this image taken by the Mars Color Imager, known as MARCI, onboard MRO. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS)

Somehow, Spirit had not gone into an automatic low-power fault mode. "That was a shock to us," admits Sharon Laubach, of JPL, MER’s integrated sequencing team chief. "Most of us thought that Spirit would have gone into her low power fault mode by the time we heard from her on Thursday, because she certainly could not sustain that extremely-low power generation for long without draining her batteries."

The rovers’ low power fault modes automatically protect the vehicles from draining the batteries by shedding electronic loads until the batteries could be re-charged through the solar arrays.

Spirit, true to the MER nature, held on, and reporting that it had nearly doubled its solar power production to 161 watt-hours by following the power conservation commands it had received. The rover engineers uplinked new plans for it to continue to conserve energy for the rest of November and then through the period of solar conjunction that more or less begins today and goes through December 13, 2008.

During this time, both rovers will be taking it easy for a while. This celestial event – where the Sun moves between the Earth and Mars -- occurs approximately every two years and disrupts communication with the two rovers for about a two-week period. Consequently, both Spirit and Opportunity will be parked, working on autopilot, and more or less incommunicado.

"When you go into conjunction is kind of an arbitrary thing, like when does spring start?" Squyres noted. "What happens is the link margin or the quality of communication with the spacecraft degrades for a while and then it comes up again. At some point, you decide, okay, this is where we stop trying. But it's not like all of a sudden there's a sharp cut-off."

Regardless of when exactly solar conjunction begins and ends, the plan for Spirit remains the same: conserve power and do little more than check batteries and the amount of dust around and about and on it. "We're conserving energy and doing taus all through conjunction," Squyres confirmed.

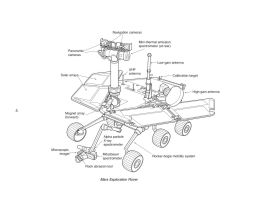

Dusty deck

Dusty deckSpirit's deck is so dusty that the rover blends into the Martian landscape in this image assembled from frames it took with the Pancam from Sol 1355 through Sol 1358 (Oct. 26-29, 2007). Dust on the solar panels reduces the amount of sunlight able to penetrate the arrays and thus reduces the amount of electrical power the rover can generate each sol. The vertical projection used here produces the best view of the rover deck, though it somewhat distorts the ground and antennas. The eight-pointed star shape near the front of the rover (bottom of image) marks the location of the camera mast, which is out of view of the Pancam atop the mast. This mosaic, in approximate true color, is a composite of frames taken through the Pancam's filters centered on wavelengths of 600, 530, and 480 nanometers.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

This past week, Spirit's power levels fluctuated as the dust levels in the atmosphere fluctuated as the dust from the storm began to fallout. However, the rover was producing 174 watt-hours of power when it last checked in several days ago, according to Laubach, much better than that new all-time mission low of 89 watt-hours and slightly better than when it phoned home November 13.

Unfortunately, there is no indication that the storm that dumped on Spirit brought any gusts at all to taketh away what it has giveth. The winds that whip up and spread the dust around the planet are, ironically, the very element that has kept the rovers alive so long. Powerful little gusts from those winds have from time to time cleared the powdery, electrostatic dust stuff from the rovers' solar arrays. "I was really hoping for a cleaning, but it didn't seem to happen," said Squyres.

“Actually, the storm blew more dust on her," Laubach said.

While the skies cleared substantially according to the data Spirit returned November 13, the dust buildup on its solar panels got thicker. Now, only 30 percent of the sunlight hitting them gets through the dust and is useable by the photovoltaic cells, down from 33 percent before the storm. As the dust storm continued to dissipate, it left the expected "residual haze," Squyres said. The haze is the dust of course and it will fallout, adding more powder no doubt to the already thick coating on Spirit's solar arrays in coming sols.

There is some good news from Gusev. After two weeks of having no heater to keep it warm, “the Mini-TES has not suffered any catastrophic failure or any ill effects that we can see," said Steve Ruff, faculty research associate, Arizona State University, Spirit's lead scientist for that instrument. "We've been able to do a couple of health checks, very modest activities to keep the power consumption down even on those."

Truth told, they thought maybe Mini-TES would survive based on the fact that Opportunity's Mini-TES has survived for years now in DeepSleep modes where its heaters are shut off along with everything else. "The Mini-TES instruments are turning out to be very robust to this kind of thermal cycling and very low temperatures," Ruff noted.

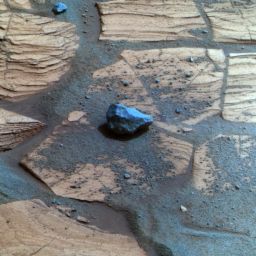

Opportunity finds Santorini

Opportunity finds SantoriniBefore solar conjunction, the celestial event where the Sun moves in between Mars and Earth, essentially cutting off communciation for a couple of weeks, Opportunity roved up to a tiny rock named Santorini on its Martian day or Sol 1713 (Nov. 16, 2008). Later that same sol, the rover positioned the instruments on the end of itsrobotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD) on the cobble and prepared to take a nice long measurement of its composition during the communications hiatus.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Since Spirit is farther away from the equator than Opportunity, it has generally experienced colder temperatures in Gusev than its twin has in Meridiani Planum. But they are on Mars and that is not always the case. On November 25, Spirit's Sol 1741, the diurnal range of atmospheric temperatures it experienced was from -30 degrees C to -95 deg C, while on the same day, Opportunity's Sol 1721, was approximately -27 deg C to -107 deg C. Spirit appears to be experiencing warmer temperatures as a result of being parked on bedrock, which heats up more during the day and takes longer to give up that heat overnight, thus keeping the rover a bit warmer than it would be otherwise. Opportunity only recently arrived to park for a while on bedrock, so this picture could change again soon.

In any case, Spirit from the very beginning has always been the more challenged of the identical twin robot field geologists, because of its particular location more than anything else. Its most recent woes have been especially difficult for the team, Laubach admitted, but not defeating. "We’re not thinking Spirit won’t make it to her fifth anniversary,” she said. “We’re expecting to be celebrating both rovers’ anniversaries in January.”

Although Spirit’s team took a break for Thanksgiving, they are mentally "dug in,” as always. “It’s going to take a lot to put that rover down,” said Laubach.

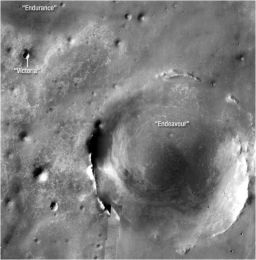

As difficult as November was for Spirit, it seemed to be a breeze for Opportunity. Bounding with power levels ranging from around 565 watt-hours to just below 600 watt-hours, this rover seemed to almost glide effortlessly across the plains of Meridiani on its 12-kilometer journey toward the really big hole in the ground the team has dubbed Endeavour Crater. At 22 kilometers (13.7 miles) wide, the entire island of Manhattan would fit neatly inside this monster bowl.

Opportunity's objective for November was to get to an intermediate destination of extensive outcrop of layered rock, which the MER team could see in the high-resolution images taken from orbit by the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) onboard MRO. "We nailed it," said Squyres.

It followed that accomplishment with another achievement -- roving right up to a cobble where it will spend the next two weeks during solar conjunction – and then another -- placing the Mössbauer spectrometer on it with the first try.

Santorini

SantoriniOpportunity used its panoramic camera to take this false color image of Santorini, the cobble it will be studying up close through solar junction. The rover snapped the picture on its Sol 1713 (Nov. 17, 2008), the same day it nudged up to it and puts its instrument deployment device (IDD) on its surface.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Since leaving Victoria Crater on Sol 1682 (October 16, 2008), the rover has logged 1,253 meters or 1.25 kilometers (0.77 mile), an impressive demonstration of just how serious Opportunity and its ground team are about their latest Endeavour.

The tau or amount of dust in the sky over Meridiani did go up, but it wasn't by much. "It's getting into the time of year when the tau is volatile, so we’ll see the dust levels bouncing around for both rovers," said Squyres. "But Opportunity is in such good shape that tau fluctuations of the magnitude we typically see at Meridiani Planum this time of year are not expected to be a factor."

The dust is, however, still a factor for Opportunity's Mini-TES. The team attempted to "shake" or vibrate the top mirror on the instrument again in November, again to no avail. "There was no apparent clearing," reported Ruff. They're not giving up.

The next plan is to simply open the cover on the instrument and expose it to the Martian elements, and wait for just the right gust of wind to clear the powdery substance. But no one seems to be terribly optimistic that will clear the dust either. "The reality is there's likely dust more surfaces than just that mirror that we can shake," Ruff explained. "There are other optics – another mirror and another window even that are down in the bottom of the Pancam mast assembly and those are likely components to be dusted as well. In that case, there's no way that we can actively try to remove dust from those surfaces."

As solar conjunction sets in, Spirit and Opportunity go into autopilot for the next two weeks or so. Both rovers prepared for the period of communications blackout that begins today by clearing their slates or unloading the accumulated backlog in their flash memories in October and early November, to free up room for the science and engineering data gathered while they are incommunicado.

Spirit "bumps" upslope

Spirit "bumps" upslopeSpirit succeeded in October in "bumping" or making short moves up the northern slope of Home Plate, where it hunkered down through its third Martian winter. This month, the moves didn't go so well. This animation is composed of four views taken with the forward hazard avoidance cameras, which are mounted just below the solar panel deck in front of the rover.

Credit: NASA / JPL / animation Michael Howard

Even before the storm, the rover team had not planned to drive Spirit away from its location until after the blackout period was over, so Spirit will be spending the solar conjunction period, according to plan, on the northern edge of the circular volcanic formation called Home Plate, where it’s been for more than eight months.

Opportunity, meanwhile, will be trying to determine the iron content of the Santorini cobble with the German designed and built Mössbauer spectrometer.

Despite being naturally a "little nervous" about the rovers during solar conjunction and the two-week period of communication blackout, the team remains cautiously optimistic about Spirit. "We feel confident that we can keep the vehicle alive and healthy if we don't get hit by some monster dust storm," said Squyres. "But we could sure use a gust of wind to clean the dust off some."

"We’re definitely hopeful about what we see on the other side," added Laubach. "We all have our fingers crossed that we’ll get on the other side of conjunction and find that Spirit's had a cleaning event and she’s back to 600 watt-hours or more."

That's a big wish. One that is not exactly in the rover's control right now. Things are getting tougher for Spirit – certainly not because of a failing in the dedication of the rover team or even in the robot’s uncanny "desire" – but because of Mars.

"Our next uplink planning cycle is December 14 and that's when we'll start commanding the vehicles again," said Squyres. Until then, as he is wont to say: It’s up to Mars.

For now, however, Spirit is very much alive, following commands, and conserving power contrary to confusion created in the media when Phoenix, the north pole lander, passed away around the same time the storm hit the rover.

Still, the next two weeks are going to be, in Laubach’s words, “pretty quiet.”

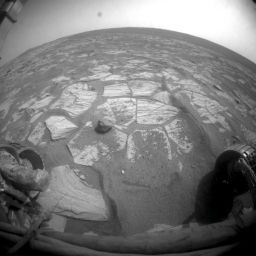

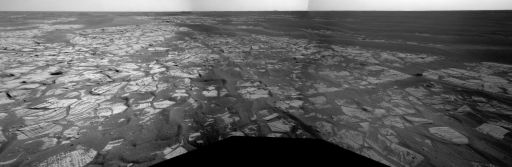

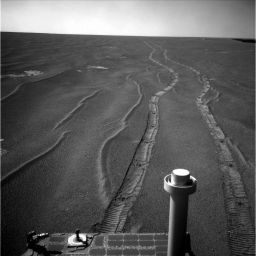

Opportunity's view just before solar conjunction

Opportunity's view just before solar conjunctionThis is a small portion of the view from Opportunity's navigation camera as it paused on its drive to Endeavour Crater, to wait out the Mars solar conjunction. The rover is currently parked on an area of bedrock that is relatively clear of the dark and tenacious Meridiani sand. The full panorama may be viewed and rotated in this Quicktime VR view, produced by Michael Howard (3.5 MB).

Credit: NASA / JPL / mosaic by Emily Lakdawalla

Spirit from Gusev Crater

As November fell on Mars, Spirit was pretty much exactly where it was as Halloween spooked Earth, trying to drive up slope onto the top of Home Plate. Beyond achieving a more favorable tilt of its solar panels toward the Sun as it moves higher in the sky, moving up would position the rover to be able to take the shortest route – across the volcanic formation – to its next set of attractions to the south, a mesa and non-circular hole in the ground to the south, named for rocket pioneers Werner von Braun and Robert Goddard.

While Spirit had made promising progress at the end of October, with successful “bumps” or short moves on Sols 1709 (October 23, 2008) and 1713 (October 27, 2008), subsequent drives during the first week of November were not so successful. When the rover tried to inch forward onto Home with on Sol 1718 (November 2, 2008), it veered to its right. "We successfully moved up some and then started seeing sideways movement," confirmed Laubach.

Spirit shimmies sideways

Spirit shimmies sidewaysSpirit continued its attempt to bump up the slope of Home Plate as October gave way to November, but a drive on its Sol 1715 (October 31, 2008), resulted in a sideways shimmy instead. Two subsequent drive moves during the first week of November also took the rover sideways. An animation of Spirit's motion from Sols 1709 to 1715 can be downloaded here (Quicktime).

Credit: NASA / JPL /animation by Michael Howard

Since the right front wheel is frozen and no longer moves, if it did slip off the top edge and onto the slope it could be extremely difficult to get it, and thus the rover, back on top of Home Plate from the position in which it is in now. As fallbacks, the engineers could always direct the rover to drive downslope and take an alternate route back up Home Plate or back down and go around the elevated plateau.

Those were looking like valid options when Spirit’s next attempted bump up, on Sol 1721 (November 5, 2008), veered the rover to its right again, this time pushing the broken right front wheel right to the very edge of Home Plate.

While the engineers -- who always manage somehow to keep the rovers roving -- were deciding on what move Spirit would make next, the robot field geologist focused on its science agenda.

During the first week of November, Spirit acquired four, time-lapse movie frames in search of clouds with the navigation camera, completed a "quick fine attitude" adjustment to determine its precise position relative to the Sun, and took some images with the rear and front hazard-avoidance cameras, as well as used visual odometry, to track its actual position based on the surface imprints made by its wheels. In addition, it measured the tau or dust-related changes in the sky every sol or Martian day with its panoramic camera (Pancam) and also checked for drift or changes with time in the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) before using it to conduct a series of mini-surveys of the sky and ground.

Before the rover’s engineering team had a chance to instruct Spirit to try again to push uphill, the weather report from the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) sounded an alarm. From orbit, the instrument showed thick, swirling dust clouds advancing from the west and heading straight for Spirit.

On Saturday, November 8, 2008, Bruce Cantor, of Malin Space Science Systems, a MARCI co-investigator, sent the MER team a weather alert that a large, regional dust storm was heading toward Spirit. Within hours, members of the MER team were heading into JPL. They uplinked commands to Spirit to delete planned communications for Sol 1726 (November 10, 2008). That would conserve much-needed energy.

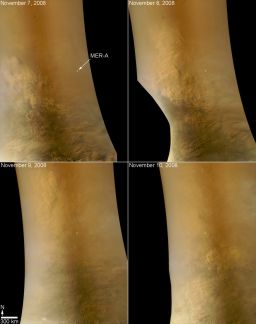

MER-ci MARCI

MER-ci MARCIIn this series of images taken with the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, you can see how the Martian dust storms blur the atmosphere and mute the landscape. From orbit, the instrument showed thick, swirling dust clouds advancing from the west. The MARCI team passed that advance weather warning to the MER team, which in turn was able to respond quickly and effectively, instructing the rover to conserve energy. They told Spirit to turn off a heater and do only two things each day -- check battery power and dust in the atmosphere. On Nov. 13, 2008, as directed, the rover phoned home and its ground team cheered.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Spirit’s average solar power production of about 250 watt-hours – compared to more than 900 watt-hours in the early sols after landing – had dropped in October to 230 watt-hours. Although that is, by MER standards, low, it had been enough for the rover to carry out its driving moves and science assignments, according to Jake Matijevic, of JPL, chief of rover engineering. But it wasn’t enough for Spirit to get dumped on by a dust storm and emerge still functioning nominally or, in robot terms, power positive.

The team received a report from Spirit on Sunday (November 9, 2008) and learned that the rover was witnessing a spike in atmospheric opacity (tau) to 2.3 and that its solar power had plummeted to 89 watt-hours -- a record low for either rover, beating Opportunity’s lowest low of 127 watt-hours during the global dust storm of 2007.

Spirit’s power was so low, it caught the team by surprise, according to Laubach. They knew there was “no way” the rover could sustain that extremely low power generation for long without draining its main batteries.

The MER team prepared two plans for uplink to Spirit on Monday, November 10, 2008: a nominal plan and a contingency plan. The nominal plan was extremely conservative with regard to power, permitting Spirit only to be awake briefly to collect data essential to monitoring the health and safety of the vehicle, basically check battery power and dust in the atmosphere. It also instructed the rover to disable the Mini-TES heater even though it meant risking damage to the instrument from the beyond freezing, nighttime temperatures. That would save about 27 watt-hours each sol. Then, they hoped for the best.

The team knew the dust storms were looming, but the timing was hard to take. "Frankly was a real blow," said Laubach. "This team has worked really hard to scrimp and save and nip and tuck to keep the heater on through winter solstice. Right when we thought we were coming out of that, to be just hit by the reality of that so suddenly was a blow to the morale.”

Despite the fact that the Mini-TES on Opportunity has survived for nearly five years without a heater, the initial reaction to the decision to pull the heater plug on Spirit’s was “one of concern," confirmed Steve Ruff, of Arizona State University, who oversees the sol-to-sol activities of the instrument on Spirit. "There's no guarantee that they're identical in all of their behaviors, and actually they aren't. This instrument may not fare as well as the other one on Opportunity." Time would tell.

The nominal plan included only one short UHF communication session on the afternoon of Sol 1729, Thursday, November 13, 2008. The session would only happen if the Spirit did not trip a low power fault. The contingency plan, on the other hand, allowed engineers to listen for a signal at specific time intervals, known as communications windows, in the event Spirit did go into low power fault mode.

Since the team would not hear from the vehicle until November 13 in the nominal case, engineers continued to listen for Spirit during an established time set aside for fault communications, just in case. They heard nothing. And the silence told them nothing. It could mean that the rover was under normal, low power sequence control or it could mean it had experienced a low power fault and did not have sufficient energy to support communications.

The answer to the mystery arrived shortly after 11 a.m. PST Thursday, November 13, 2008. Spirit phoned home, sending a normal transmission via its UHF antenna to the Odyssey orbiter, which in turn relayed the signal to Earth. The team cheered.

It turned out that Spirit had not tripped the low power fault mode and that surprised the team. “Most of us thought that Spirit would have gone into her low power fault mode by the time we heard from her on Thursday,” Laubach said.

They learned that Spirit’s solar-array power had instead nearly doubled, increasing to 161 watt-hours, and atmospheric opacity had fallen to about 1.0 from a peak of 2.3 during the storm. The hope had been the rover would get some of the dust coating its solar panels clear off by the winds that whipped up the storm. That did not happen.

Got dust?

Got dust?The global dust storms of June-July 2007 left a Sun-blocking haze in the atmosphere and a thick sunscreen of particles on Spirit's solar panels. As winter set in and the skies cleared, more dust fell and so far this rover has not been graced with any clearing wind gusts.In fact, it took on more dust this month from a passing storm

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / USGS

Rather, Spirit, appears to have taken on more dust, said Laubach, given that its dust factor had dropped since the storm.

According to the downlink, the rover's dust factor was 0.33 before the storm, dropping to 0.30 after the storm. The translation is, indeed, bleak -- only 30 percent of the sunlight reaching the rover’s solar panels was penetrating the coating of dust to generate electricity. Nevertheless, the rover was alive and listening and talking.

Spirit’s near-death experience and comeback proved another example of the undeniable resiliency that has come to define the Mars Exploration Rovers. Of course, it’s every bit as much testament to the efforts of the men and women who designed, built, and operate these hardy robot field geologists – and who are well aware they cannot rove forever.

All in all, it turned out to be a good week. The MER team could be nothing less than elated about their Spirit and they celebrated with home-baked brownies, courtesy of Dina El Deeb, MER’s Strategic Engineer for Mission Assurance Management.

In the plans uplinked on November 14, Spirit was ordered to limit activities to those necessary for maintaining engineering health and safety. After briefly observing the sky with the Mini-TES on Sol 1730 (November 14, 2008), the rover spent the next three sols, 1731-1733, resting and soaking up the Sun's rays to recharge the batteries.

Spirit endured yet another challenge when new commands from Earth for Sol 1734 (November 18, 2008) did not arrive. At that point, the rover automatically began to execute a backup set of activities known as a runout plan and continued executing that plan for the next two sols.

On Earth, engineers created a new sequence of commands for Sol 1736 (November 20, 2008) to manage communications and preserve power. Meanwhile, they began investigating why Spirit did not receive their previous commands.

Currently, Mars weather reports indicate that the ferocious little dust storm has dissipated. No other storms have been identified within a couple of thousand kilometers of Spirit's location and the sky over Gusev Crater is expected to continue to clear during the next few weeks. There is still a lot of dust suspended in the atmosphere, however and, as the sky clears, some of the powder-fine substance – no one can say how much -- will fall onto Spirit's solar arrays, thickening the layer already covering the panels.

Spirit at Home

Spirit at HomeThis image, taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard MRO, shows Spirit at its approximate current location on the northern edge of Home Plate in the Columbia Hills, at Gusev Crater. The picture was taken during the southern hemisphere winter solstice at about 2 p.m. local time on the rover's Sol 1591 (June 24, 2008). Home Plate is the elevated round and light toned mesa on the right side of the image. Spirit is the little dark "bump" on the north-northeast edge of the circular volcanic formation. Mid-winter on Mars is the time of the clearest and least dusty atmosphere.

Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

Making the prospects of survival even more challenging, Spirit probably will see more seasonal storms of this nature over the next few months. “This is the time of the Martian year when storms like this can occur,” John Callas, MER project manager at JPL, reminded. "The plan ahead is to stay cautious with the rover.”

The MER team will continue to monitor power and weather conditions closely. They will also continue to monitor the Mini-TES and plan to turn the heater back on as soon as it is safe to do so. Despite their determination, Spirit's setback in November hit the team pretty hard. After a long, stationary Martian winter, everyone on Spirit’s shifts was ready, willing, and anxious to rove on. "There has been a change in mood,” said Laubach. “It went from Spirit successfully bumping up on five wheels, changing her tilt from about 30 degrees to 25, to all of a sudden getting hit by this dust storm, and going back to stationary low power ops.”

Where there is darkness, however, there is still light. Although Spirit is in a serious power situation, all subsystems have been performing as expected and late word is that the Mini-TES has apparently survived its first couple of weeks without nighttime heat. "It turns out, Spirit's Mini-TES does seem to be doing as well as Opportunity's," says Ruff. "It looks like it's doing fine and I think the Mini-TES will come through. As we continue to get good health checks, my concern is fading as the days go by. It’s the fate of the rover that is actually more of a concern now. Can we come out the other side of conjunction with a rover that makes it through and can actually move around and do some science?”

That is the $64,000,000-dollar question (with inflation) for MER right now.

Spirit shifted to its solar conjunction plan today, which essentially is more of the same routine as the last two weeks, take taus or measurements of dust in the atmosphere, check batteries and otherwise rest, and conserve all the energy it’s got.

While Spirit’s solar conjunction will go from Sols 1746-1760, there won’t necessarily be a full-scale communications blackout, Laubach said. The team, actually, will attempt to touch base with the rover over the next two weeks. Beyond the passes just before and at the end of conjunction, there are several Odyssey relays scheduled in the midst of the celestial event, one on Sol 1748 (December 2, 2008), another on Sol 1754 (December 9, 2008), and an MRO relay on Sol 1757 (December 12, 2008). There are no guarantees though. These relay sessions will probably be spotty or may not return any data at all.

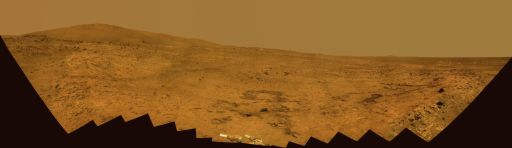

Bonestell Panorama, south view

This 180-degree panorama shows the southward vista from Home Plate North, where Spirit is spent third Martian winter inside Mars' Gusev Crater. Home Plate, which is about 80 meters (260 ft) in diameter, is an eorded over volcanic formation. This view combines 168 different exposures that Spirit took with its Pancam -- 42 pointings with 4 filters at each pointing. Spirit took the first of the images that are combined into this view on its Sol 1477 (Feb. 28, 2008), two weeks after the rover made its last move to reach the location where it would stop driving for the winter. Solar energy at Gusev Crater is so limited during the Martian southern hemisphere winter that the rover does not generate enough electricity to drive, nor even enough to take many images per day. The last frame for this mosaic was taken on Sol 1599 (July 2, 2008). Spirit is to finish taking images for the northern half of the scene during the Martian spring.

The northwestern edge of Home Plate is visible in the right foreground. The blockier, more sharply shadowed texture there is layered sandstone whose layering is tilted inward toward the edge of the Home Plate platform. A dark rock on top of Home Plate in that area is a porous volcanic basalt unlike rocks nearby. The northeastern edge of Home Plate is visible in the left foreground. Spirit first climbed onto Home Plate on that region, in early 2006. Rover tracks from driving by Spirit are visible on Home plate in the center and right of the image. These were made during Spirit's second exploration on top of the plateau, which began when Spirit climbed onto the southern edge of Home Plate in September, 2007. In the center foreground, the turret of tools at the end of Spirit's robotic arm appears in duplicate because the arm was repositioned between the days when the images making up that part of the mosaic were taken. On the horizon, the highest point is McCool Hill. This is one of the seven larger hills in the Columbia Hills range.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

If on the other side of solar conjunction things do improve for Spirit, it will try again to rove back up on top of Home Plate. "We’ve certainly not run out of the options we could try," said Laubach. If things don't improve, the solar-powered rover will eventually likely go into self-induced, low power fault mode.

Since the MERs are solar-powered there is really no way to take Spirit off off-line and put it in a hibernation mode, say, unless it goes into the low power fault mode. That, in essence, would be a kind of hibernation. Everyone’s hoping it won’t come to that -- not yet anyway.

Still, there may be many more surprises to come on this mission. Consider that if Spirit did go into a low power fault mode, the rover could resurrect later when, say, a wind gust clears its arrays. In other words, it won't be over – until it's over. "If anything can be done to pull Spirit through this,” Laubach said, “the team will do it.”

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

Opportunity roved into November on Sol 1697 with just under 600 watt-hours of power and put the pedal to the metal again. It logged another sporting drive toward Endeavour Crater, taking the usual pictures just before and after ending the drive with the navigation camera and panoramic camera (Pancam). It then relayed data, as usual, to Odyssey then went into a DeepSleep.

Changing terrain

Changing terrainFor every sol Opportunity drove this month and last, it had to chose a route through one of two kinds of Martian terrain -- one hard and smooth, the other soft and sandy, both of which are shown in this flicker pic, comprised of images the rover took with its navigation cameras and Pancam. Paving the way are flat-lying rocks formed long ago with help from liquid water. Threatening to bury the rover's wheels are waves upon waves of sand ripples. Both features fill the region that separates the Mars rover from Endeavour Crater. The trick is not getting snared in another purgatoid or sand dune trap.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

During the last couple months or so, Opportunity has been taking a route through two kinds of Martian terrain – one features flat-lying rocks formed long ago with help from liquid water, making for a mostly smooth, hard surface. The other, waves upon waves of sand ripples, is a soft and sandy kind of topography that constantly threatens to bury the rover's wheels.

These two types of terrain, which fill the region that separates the Mars rover from Endeavour Crater, will be Opportunity’s landscape for the foreseeable future. As much as possible, the rover will be directed to stay on the rocky part of the road and avoid the sandy seductions as much as possible or, in other words, make sure that the rippled terrain of waves is the road less traveled.

In the first week of November, Opportunity spent some quality time measuring atmospheric argon with its alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) and using the Pancam to snap some pictures of its tracks, as well as the albedo or surface reflectivity of the ground around it. Like Spirit, it also regular took daily measurements of dust-related changes in atmospheric clarity with the Pancam, as well as regularly monitoring the dust accumulation on the camera system's mast assembly.

Opportunity also completed downlinking or eliminating most hold-over science observations, as well as auto-navigation drives from its flash memory at the top of the month to free up room for science and engineering data to be collected and store during solar conjunction. The need to free up memory actually impacted the rover’s driving in November, for the simple reason that it takes a memory to drive alone.

The MERs have two modes of driving: autonav [automatic navigation], where they get to choose their path using their own computer brain; and blind drives, where the engineers on Earth guide the rover using three-dimensional maps and images of Mars. Engineers permit autonav only where terrain is fairly predictable, for obvious reasons.

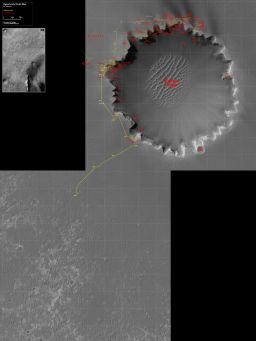

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapBy Sol 1691 (Oct. 25, 2008) Opportunity was more than 400 meters to the southwest of Victoria crater, which it departed on Sol 1682 (Oct. 16, 2008). The rover headed for an area where the north-south dunes of Meridiani Planum are spread thinly over exposed bedrock, a landscape that would provide the rover with a kind of "paved" road southward on its 12-kilometer journey toward Endeavour Crater. The inset to the upper left shows the land between Victoria and Endeavour. Grid lines are spaced 100 meters apart.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / Eduardo Tesheiner

Interestingly, Opportunity’s most efficient drives of late seem to be those where its uses a combination of the two driving modes. The rover recently achieved near-record drive distances by using autonav drives at the end of blind drives. The greater distances come at a price, however, because the autonav drives generate a lot of data. Since the goal became gaining as much distance as possible while still keeping an eye on data volume in November, Opportunity returned to doing shorter blind drives as the month wore on, to keep flash memory data volume to necessary levels.

The skies above Meridiani got hazier over the past month and the tau, a measure of the darkness caused by atmospheric dust, increased a little to 0.478, even though Opportunity did not experience a storm like Spirit did. At the same time though, this rover’s dust factor, the measure of the fraction of sunlight penetrating dust on the solar arrays, remained relatively stable at 0.7151, meaning it was processing more than 70 percent of the sunlight hitting the arrays for power. As a result, the team has attributed the increase in haze to the arriving spring season.

As the second week of November took hold on Sol 1704 (November 8, 2008), Opportunity took stock, surveying the horizon, taking pictures of surface ripples and looking for the pearl-shaped mineral deposits known as "blueberries" with the Pancam. The rover then, resumed driving, taking the usual images at the end of the drive with the navigation cameras and the Pancam, uplinked data to Odyssey, and went into a DeepSleep.

During the ensuing sols, Opportunity shook – actually vibrated – the top mirror of the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) in an effort to remove dust that seeped onto it during the global dust storm of June 2007. The rover also took more measurements of atmospheric argon with the APXS, completed another horizon survey with the Pancam, and took a six-frame, time-lapse movie in search of clouds with the navigation camera.

Unfortunately, the analysis of the post-shake images of the sky and ground with the Mini-TES -- as well as navigation-camera images that documented the conditions -- indicated that, again, the shake tests did nothing to clear the instrument's mirror.

Opportunity's next big destination

Opportunity's next big destinationThe MER team chose a a crater more than 20 times wider than Victoria Crater as Opportunity's next destination. The rover began the long, 12-kilometer (about 7.5-mile) journey -- which p.i. Steve Squyres estimates will take about 2 years, with science stops along the way -- on Sep. 26, 2008 with a 152-meter drive. The crater is located to the southeast of the rover's previous location at Victoria Crater and dominates this orbital view from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) camera onboard Mars Odyssey orbiter. Victoria is the most prominent circle near the upper left corner of the image. This view is a mosaic of about 50 separate visible-light images .Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASU

On Sol 1707 (November 11, 2008), Opportunity hit the Meridiani Plains highway again for another day of driving, keeping to schedule in order to reach the next intermediate destination before solar conjunction blocks communications.

Two sols later, on Sol 1709 (November 13, 2008), the rover took off again, this time on a 93-meter (310-foot) drive that took it to that destination, a large expanse of bare outcrop that the team had seen in the pictures taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

The team had been hoping to find a nice, good-sized cobble (small rock) for Opportunity to examine up-close during the coming solar conjunction, and the lucky little rover homed in on one just when the team was almost about to give up hope. It had driven just 17 meters (56 feet) on Sol 1710 (November 14, 2008) when it spotted a choice cobble just about 8 meters (30 feet) away.

Three sols later, on Sol 1713 (November 17, 2008), Opportunity set out on an 8-meter drive that took it right up to the cobble the team would dub Santorini, within reach for science instruments on its robotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD).

The MER team has chosen islands are the namesakes for the cobbles Opportunity will encounter and this cobble is named after the small archipelago of volcanic islands in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 kilometers southeast from Greece’s mainland. The sunsets on Santorini are said to be “the best in the world.”

“These cobbles are like little islands out in the sea, and I figure we’re going to see a lot of cobbles and there are a lot of islands,” explained Squyres.

After looking for a few months for a good cobble to study, it’s almost strange that Opportunity found a really good one just in time for solar conjunction. But, given this rover’s history, not really strange.

"I am thrilled with the cobble," Squyres said. "We have been looking for a good size cobble that we could be on for conjunction and we drove and drove and weren't seeing any cobbles. I was getting really frustrated. Then, right when we needed one – boom – there's Santorini. Big and juicy and right there in front of us. " Then, things got even better for Opportunity.

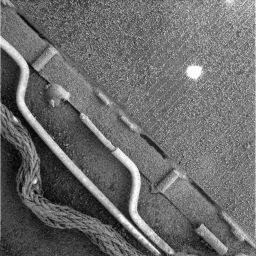

Opportunity's IDD on Santorini

Opportunity's IDD on SantoriniIn preparation for a break in driving over Mars solar conjunction in November 2008, Opportunity placed the "hand" of its robotic arm in position to do a long analysis on a small rock called Santorini.Credit: NASA / JPL

Since Opportunity is not able to change the azimuth of the shoulder joint, that is, move it from side to side, because the shoulder azimuth joint (Joint 1) was disabled due to degraded performance, the placement of the science instruments on Santorini using only 4 degrees of freedom of the robotic arm, instead of the usual 6, was the challenge. Together, the rover and its ground team met that challenge on Sol 1714 (November 18, 2008), as Opportunity successfully placed the Mössbauer spectrometer on a faceted surface of the cobble.

"We put the Mössbauer spectrometer on it and nailed that placement on the first try," Squyres said. The contact switches on the instrument confirmed that the spectrometer had touched the surface. The instrument was turned on and the analysis of the cobble’s iron content got underway.

"This is the first time we’ve tried to do in situ measurements on a cobble since the shoulder azimuth joint was disabled," Laubach pointed out. “We had done IDD measurements on that ripple at Duck Bay, but that was a nice broad target. This was the first time where we had a very specific target we wanted to hit and the team did the placement on the first attempt."

Ironically, she noted, that gave Opportunity's engineers less to do. "We were expecting to take that week and a half leading up to Thanksgiving doing the fine positioning and re-trying the placement. But they got them both on the first try and kind of put themselves out of a job until after conjunction," said Laubach.

"With all the experience in the crater and on the plains and going through the dunes around Purgatory and now south of Victoria, this team thoroughly understands this rover,” she continued. “We don’t expect to have this kind of luck every time, but it’s nice to see the rover planners validate their approach of how to put the IDD on these targets works."

Opportunity looks back

Opportunity looks backAfter a drive of more than 150 meters on Sol 1663, Opportunity took a day of rest to look around and contemplate its tracks on the rippled sand of Meridiani Planum.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Opportunity took advantage of the extra time and to snap some pictures for a panorama using multiple filters of the Pancam, measure atmospheric argon using the APXS, and create the occasional, time-lapse movies of clouds with the navigation camera, as well as keeping daily tabs on the amount of dust is in the atmosphere.

The rover again shook the Mini-TES mirror again during the next weekend, but analysis of the post-shake images of the sky and ground with the instrument -- as well as navigation-camera images to document conditions – indicated, again, there was no change in the instrument’s obscured optics.

Opportunity is currently parked on the “broad expanse of pavement, of fractured bedrock," as Squyres described it, and will remain there now for the next few weeks. "There are drifts and purgatoids around us,” he said, “but we're on mostly bedrock.”

Throughout November, Opportunity continued its routine of regularly going into DeepSleep, a mode where it shuts down systems, turns off everything, including heaters, for the night. The rover began this routine not long after landing in January 2004 when engineers discovered that one of the heaters in its warm electronics box was stuck in the ”on” position and draining precious energy and it will continue its DeepSleeps as the mission continues. So far, the rover doesn’t seem much worse for the cold.

“Things are pretty good at Meridiani Planum these days,” Squyres summed up.

In fact, things really couldn’t be much better for Opportunity. "Where we are right now is a really good place to be for solar conjunction,” he said. “We've got this big juicy cobble right in front of us and the Mössbauer spectrometer is down on Santorini and cranking away and we're already getting data from it.”

It's “too early to say" exactly what that data reveals, said Squyres. However, "some of the early betting within the team" is that Santorini is going to turn out to be a meteorite. "Right now we don't know," he cautioned.

Rove on, Opportunity

Rove on, OpportunityThis rendered image of Opportunity is an image produced using "Virtual Presence in Space" technology, developed at JPL. It combines a photorealistic model of the rover and a false-color mosaic taken by the rover on Sol 134 (June 9, 2004) with its panoramic camera while in Endurance Crater. Credits: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / rover model by Dan Maas /synthetic image by Zareh Gorjian, Koji Kuramura, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong

With a continuously decaying radioactive source, the Mössbauer spectrometer signal strength now is much, much lower than it used to be, so it takes a really long time to get a useable Mössbauer spectrum. “Remember, we just started and we have a beautiful, long time period now to get a really good Mössbauer integration, then we still have to do the APXS,” he added.

Since leaving Victoria Crater on Sol 1682 (October 16, 2008), Opportunity has driven 1.25 kilometers (0.77 miles), a little more than one-twelfth of the way to Endeavour Crater and once solar conjunction is over, the rover won't waste any time moving on. "As soon as we're commanding again – December 14 – we will wrap up the Mössbauer integration, take the microscopic imager pictures and APXS measurements on Santorini,” Squyres said. “Then, we'll be on our way."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth