A.J.S. Rayl • Nov 30, 2007

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Thrashes with Tartarus, Opportunity Wrestles RAT at Victoria's Ring

Nail-biting drama and the inevitable signs of aging marked the month of November for the Mars Exploration Rovers, with Spirit accidentally encountering Tartarus, a dust-filled crater, on its way to its winter haven and having to thrash for its life, and Opportunity spending a lot of its time conducting tests on its RAT (rock abrasion tool), which lost another encoder.

But true to their resilient robot natures, the roving field geologists persevered, even worked in the face of hardship, and managed to chalk up another respectable month of exploration and experience.

As the Martian winter looms large on the horizon, the spotlight remains on Spirit at Gusev Crater. Although Opportunity took the brunt of the global dust storm in July, it is Spirit that is now suffering the most from the fallout of the summer storm. In the weeks after the storm whirled itself out in August, Opportunity was graced with a series of wind gusts that cleaned much of the accumulated dust from its solar panels. Spirit only experienced one, minor wind gust in October that resulted in a modest 10 watt-hour boost in power; consequently, its solar arrays are laden with dust.

With no wind in sight or in the forecast and given the fact that Spirit's location is not quite as close to the equator as Opportunity's site and thus will likely experience colder winter temperatures, the negative impact on the rover's energy is a no-brainer. Spirit's power levels in all probability will plummet to life-threatening levels as winter sets in. Even if the MER team weren't comprised of rocket scientists, it would have opted for the obvious -- get the rover to its next winter haven sooner rather than later.

The MER team chose that new haven November 1 and Spirit literally drove into the new month, following commands to head to Home Plate North, where it will hunker down for the next six to eight months. Along the way, it continued its picture-taking campaign of the West Valley to see if it might be a potential route to take south of Home Plate next spring, to get to two geologic targets of intense science interest, a hill named von Braun and a sunken sort of formation dubbed Goddard. Only one in-depth science study, however, of a rock called Pecan Pie was actually scheduled into Spirit's science agenda during the drive to Home Plate North.

By mid-month, Spirit had sent home that data, an early Thanksgiving gift you might say for its team, and moved on toward Site 6 and then Site 7 and a hummock to get "a good view" and new perspective of the West Valley. Somehow, as it roved northward along the western margin of Home Plate on Sol 1378 (November 18, 2007), Spirit rolled right smack -– all six wheels -– inside a shallow, dust-filled crater, where it spent most of the rest of November.

"We drove into this crater not realizing what it was until we were in it," Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, principal investigator for rover science, informed during an interview yesterday. "It wasn't a big, steep-sided hole the ground. These were gentle slopes. But Spirit has trouble with gentle slopes."

The crater was small indeed, "a little over a rover length in diameter, around 2 meters, with a 10-centimeter (about 4-inch) lip," according to Jake Matijevic, chief of the rover engineering team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were designed and are being managed. It may not seem like much of crater, "but it was big enough to cause us trouble," Squyres said. "This was just an insidious trap waiting for us. We sunk well down into this bowl-shaped crater with a lot of loose soil in it, all six wheels. We were stuck. It was a bad situation."

The little 10-centimeter (4-inch) tall lip, which was consistent all the way around the depression, was for the five-wheeled Spirit a big deal. "With the rover dragging the disabled right front wheel, even a small rise represents a significant obstacle," Matijevic explained, because "dragging results in the right front wheel embedding into the terrain."

After a week and a half of thrashing, popping at least one wheelie, the rover was only digging in deeper. On Wednesday, November 28, RPs sent up a series of commands instructing Spirit to do the dangerous -– drive forward. "If [Wednesday's] drive didn't work, I don't think we had too many other cards to play," Squyres said. "We were basically out of tricks."

At 5 a.m. Pacific time yesterday, Thursday, November 29, the rover sent home its telemetry. "We got one of the best downlinks we've gotten on this mission," beamed Squyres. "We had an extraordinarily successful drive. The RPs were just magnificent. The intuition that they showed in designing a drive that did what it did, well, it was really their finest hour I think. We're still in a precarious position, but we've got a fighting chance now," added Squyres. Once Spirit escaped its the crater's clutches and the team members could breathe a little easier, they christened it Tartarus. It was, after all, Squyres pointed out, "a pit of torment."

The sole objective for December is getting Spirit in its winter position at Home Plate North, still an estimated 40 meters (131 feet) away. On a good day, that's a single drive. These days for Spirit, it's anyone's guess how long it might take. "Low power, beyond cutting into the science, restricts how much the rover can drive every day," reminded Bruce Banerdt, of JPL, MER project scientist. "The length of the drive must now be paced with the amount of energy," he noted. Driving, in fact, takes a good bit of a rover's energy and as Spirit's power levels dropped from 345 to 310 watt-hours in November, it was forced to devote every sol after a drive to re-charging its batteries. As a result, the MER team changed the deadline for the rover to be parked for Martian winter from January 2008 back to December 23, 2007.

"We want to be sure to make progress early on, especially now that we've lost about a week's worth of drive days due to [Thanksgiving] and this latest issue of being stuck," said Banerdt. "We're getting shorter and shorter drive days as the winter progresses, so the drive today is always better than the drive will be tomorrow.. If we get stuck a couple more times that could put us into a tight situation like we were in last winter, so we want to be conservative in our planning," he added. "And with the holidays coming up, we want to be in place before Christmas."

The RPs have "driven in this territory" of Martian winters and low energy before and while they're a little more comfortable with the lower power numbers, they are expecting levels on Spirit to go down into the same life-threatening, low range of 130 to 160 watt-hours that Opportunity experienced during last summer's global dust storm. Not surprisingly, all the available energy Spirit's got right now is going into driving.

The MER team has selected the general area at Home Plate North to which they are directing its charge. "It's right along the northern edge of Home Plate," informed Squyres. "We want to get a pure northward tilt and we think we'll get something close to 25 degrees of tilt there."

The engineers at JPL have been running simulations for various tilts. "Even at tilts on the order of 25 degrees, we could be seeing energy levels on the order of 160 watt-hours in the dead of winter, maybe lower," said Matijevic. Several significant variables are at play, of course, not the least of which is how harsh the Martian winter will be and how much more dust Spirit will accumulate on its solar panels between now and the dead of winter.

Despite the newfound urgency, there is "cautious optimism" that Spirit will survive. "After Tartarus, I'm back to feeling optimistic that we'll make it to the haven and we'll make it through winter," said Squyres. "There are an awful lot of unknowns and we've been dealing with that for years now and we'll continue to deal with it." Added Banerdt: "We're confident we can get through it, but it's definitely going to be difficult."

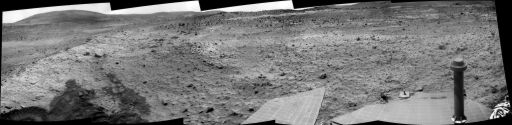

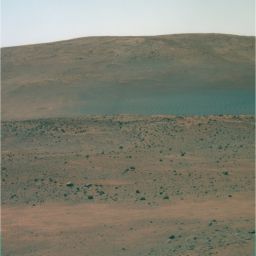

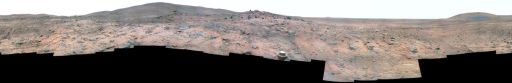

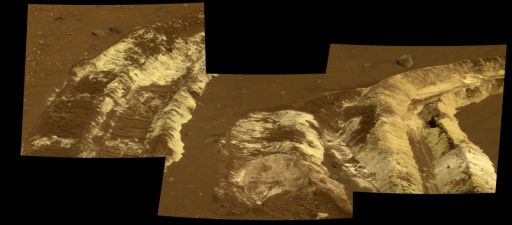

West Valley

West ValleyThis image is part of the new panorama that Spirit acquired on Sols 1366-1369 (Nov. 6-9, 2007), looking from atop Home Plate towards the valley to the west. The panoramic camera (Pancam) imaging team is still waiting for additional data to be fully downlinked in order to complete processing of the full panorama.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

On the other side of the planet, Opportunity spent November at Merdiani Planum, just inside Victoria Crater, continuing its investigation of Smith, a target in the second or middle layer of the tri-layer rock ring that encircles the interior of the massive hole in the ground. At approximately 800 meters (one-half mile) wide, Victoria is the largest crater the rover has visited, about five times wider than Endurance Crater, and 40 times as wide as Eagle Crater, where it bounced to a landing in January 2004.

Although it is sporting more than twice the amount of energy than its twin, Opportunity also encountered an issue that slowed its pace during the last four weeks, with its own rock abrasion tool (RAT). After glitching late in October, the rover conducted a host of diagnostic tests to determine the cause of the instrument's intermittent faulting.

As it turned out, the RPs discovered that Opportunity lost a second encoder on the RAT, the one that signals the actuator that spins the instrument's brush. The engineers devised a workaround to enable the rover to still use the brush, but then during a test of the planned workaround, an incorrect command sent the brush spinning the wrong direction and in split seconds, it stuck on a rock and bent. The engineers conspired again, according to Matijevic, and while the brush may not be useable in the way it was originally intended, the new strategy of another workaround for grinding into targets is slated for testing this weekend.

"This problem with the RAT has been a particularly difficult one, but the test bed work has really illuminated how to deal with it and we think we have a strategy that's going to work," said Squyres.

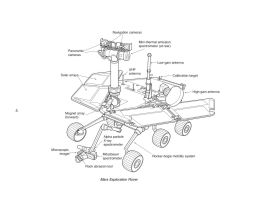

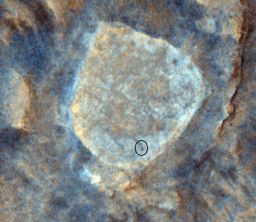

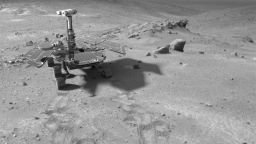

Spirit at Home

Spirit at HomeThe High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment -- or HiRISE -- camera team, led by the University of Arizona's Alfred S. McEwen, released this new image of Spirit at Home Plate this month. The rover (circled) can be seen inside the perimeter of Home Plate, where it was when the camer took the image on Sept. 27, 2007, at 2:19 p.m. local Mars time, according to HiRISE team member Ken Herkenhoff of the USGS. HiRISE, which is onboard MRO, is the most powerful camera ever to orbit another planet. At the time it took this image, the orbiter was flying about 270 kilometers (168 miles over the surface, from which it can resolve objects as small as 81 centimeters (32 inches).

Credit: NASA/ JPL - Caltech/UAz

Spirit and Opportunity may have lost a little research time in November and each struggled with issues of aging that slowed them down, but the intrepid robot geologist-explorers remain in overall good health, with most instruments still working to one capacity or another.

On November 26, the team working with the most powerful camera ever to orbit another planet -- the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), headed by the University of Arizona's Alfred S. McEwen -- released another, color image of Spirit. It shows the rover atop Home Plate, in the position it was on Sept. 27, 2007, at 2:19 p.m. local Mars time, when the camera orbited 270 kilometers (168 miles) overhead and took the image, according to HiRISE team member Ken Herkenhoff of the United States Geological Survey (USGS). As the robot field geologists rove toward their 4th Earth birthday, coming up in January 2008, the image speaks a thousand words about the value of this ongoing overland expedition of Mars.

The rovers' greatest challenges may well now lie in the wintery sols ahead. There is no exact date for the start of Martian winter –- "where you want to draw the label of winter is kind of up to you," Squyres suggested. [See McMurdo Pan Sidebar] "But it is coming," he said. "Things are tough and getting tougher."

If any rovers can beat the odds, it's these Spirit and Opportunity. Overcoming challenge is written, one might say, into their robo-nucleic acid. "Just to meet the basic objectives of the MER mission, these rovers presented a series of engineering challenges that had to be met," noted Matijevic. "The design was a leap in the general engineering of the vehicle system, as well as the robotics of the mobility." Although Mars Pathfinder's Sojourner took the first baby roves to prove the value of rover technology, "[i]t's a very different situation being thousands of meters away from the landing site, versus only 10 or so meters in the case of Sojourner. Having the vehicle in a sense encounter a different sort of environment every day they move on the surface is a major step up in the operational capability. You just don't see the same kind of challenge in missions we've flown either in orbit around planets or in other kind of flyby missions, so there's quite a bit we've learned as a consequence."

One important lesson learned is the longevity that can be offered in the designing of the general engineering capabilities of the vehicle system. "This is quite a pounding Spirit and Opportunity have taken over the course of these almost four [Earth] years, with daily thermal cycles and environment changes from one season to the next," Matijevic said. "Yet, they are well beyond what we would have asked for in the sense of their general capability, even to the extent to the resilience in the design, which has allowed us on several occasions to overcome breakdowns in the componentry. That's a testament to the basic capabilities that are in the MER system," which, he added, emanate from "a general engineering expertise [that] has been built up [at JPL] over the course of many years." That expertise, he underscored, is "what makes it possible for us to have a vehicle that can still perform successfully in challenging contexts" or, in other words, adapt to losses with workarounds."But workarounds are only possible if you actually have some resilience in the system inside."

Arguably, they are probably also only possible with a dedicated support team. Spirit and Opportunity have been roving for so long now that many of the MER team members are having to juggle duties on two or three missions. Even so, there's no slagging of interest. "There's a general recognition that this is a unique mission and a unique opportunity for us and we're certainly not blasé about the fact that this has been going on for several years," said Matijevic. "These are once-in-a-lifetime opportunities for in situ exploration on the surface of Mars and as long as they can productively perform their science functions at these sites, it's worth keeping them going." Not to mention, of course, that it's still pretty cool to come into work and drive a rover on Mars. But there's dedication and then there's dedication.

With Spirit once again in a race for its life, the MER team's actions this week reflect the seriousness of the situation as much as its unflagging dedication to the rovers. For the first time in years, MER leaders authorized planning for the weekend, instead of sending up one set of commands on Friday to cover a 3-day schedule, keeping the rover busy through the weekend as has been the general routine. "We're pushing pretty hard here," Squyres acknowledged. "This is an unusual circumstance. Winter is coming on and we've got to get this rover to a safe haven."

When it became clear that it was going to be a good idea for Spirit's ground team to work this coming weekend, Squyres and Sharon Laubach, the chief of the rover sequencing team, who also schedules almost the entire engineering tactical team, had to go to their crews and "reluctantly ask for volunteers to come in and work on the weekend," Squyres recounted. They each had to turn people away, many people away. "I could have staffed three rovers this weekend," Squyres marveled. "Sharon experienced the exact same thing on the engineering side. That says really something special about this team -- that after four years of this we still have people begging to work the weekends, to help us save this rover. It is truly gratifying. There are an awful lot of unknowns. But we've been dealing with unknowns for years and we'll continue to deal with them. "

Spirit From Gusev Crater

While the MER team on Earth spent Halloween mulling over last-minute data and considerations about where to send Spirit for the coming Martian winter, the rover worked away on Mars, checking off its assigned science tasks.

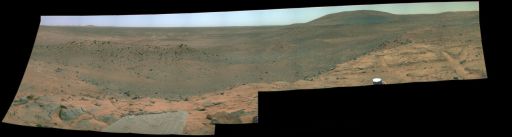

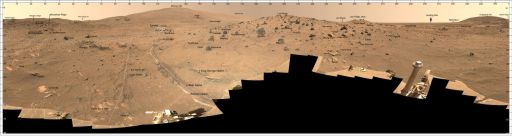

Home Plate South Panorama

Home Plate South PanoramaSpirit acquired this panorama with the Pancam between Sols 1325 - 1332 (Sep. 25 - Oct. 2, 2007). This false color rendering uses the same filters as used in the panorama shown above, but is presented in a way dramatically different from "true color" in order to enhance the many striking, but subtle, color differences between rocks, soils, hills, and plains in the scene. The Pancam team, led by Jim Bell of Cornell University, has worked to eliminateimage-to-image seams from the sky portion to better simulate the vista a person standing on Mars would see.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

Spirit spent a rather full and unfrightful All Hallow's Eve taking a mosaic of microscopic imager (MI) pictures and alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) data of a soil target called Pumpkin Pie, as well as some full-color pictures of another soil target, Candy Corn, a survey of the horizon with its Panoramic camera (Pancam), and some movie frames in search of dust devils. The rover also continued diagnostic tests on its rock abrasion tool (RAT), which had stopped functioning properly in the final days of October.

With that third RAT test, engineers determined that the grind motor on Spirit's RAT failed on Sol 1341 (October 11, 2007), just as the grind motor on Opportunity's RAT had failed on its Sol 1045 (January 1, 2007). That was just the beginning of the challenges Spirit would confront in November.

The global dust storm of the summer blew itself out in August, but the dust that it spewed high into Mars' atmosphere continued to dust Gusev Crater and Spirit's solar panels throughout the month. The rover was gifted with one light gust of wind in October that superficially dusted off its solar arrays and gave it a 10 watt-hour "bump" in energy, but it has not seen any wind since. As a result, the rovers planners anticipate its power levels to drop lower during the coming Martian winter than they did during the last Martian winter – and that means as low as the mission has seen.

Given the dust factor and power levels of 345 watt-hours and dropping, the MER team decided on November 1 (Spirit's Sol 1361) to trade location for power and head toward a winter haven on the north edge of Home Plate. It was the only one of the possible candidate locations that offered a safe 25+ degree northern slope where the rover can angle its arrays to draw in the maximum amount of sunlight fuel possible.

Ultimately, the Home Plate North location puts the rover about 10 drive sols farther away from the objects of the scientists' desire -- a hill called von Braun and nearby formation called Goddard to the south. At the same time, it will allow the rover a safer, steeper northward slope that translates into an additional 10 watt-hours. "It's a simple, straightforward trade of 10 watt-hours for 10 drive sols," as Squyres put it earlier this month. "There are lots and lots of other factors that go into this decision. Boil it all down and it really comes to that."

Up on Mars, Spirit wasted no time. In preparation for the next sol's drive, it stowed its instrument deployment device (IDD), the robotic arm with which it collects many of its data, took full-color images of tagerts dubbed Elk and San Juan, surveyed the sky at both low Sun and high Sun with the Pancam, then acquired a mosaic image with its navigation camera as part of the 360-degree panorama for drive planning.

The agenda called for Spirit to continue its routine atmospheric and dust measurements and its recent imaging campaign of the West Valley, as well as its regular communication schedule, receiving morning instructions directly from Earth via its high-gain antenna, sending evening data to Earth at UHF frequencies via the Odyssey orbiter. But only one specific target, a rock dubbed Pecan Pie at Site 5, was selected for close-up investigation. On Sol 1362 (November 2, 2007), the rover began the trek toward its winter destination, stopping mid-drive to take some full-color images of Pumpkin Pie with the Pancam, then heading toward toward Site 5 and its assignment at Pecan Pie.

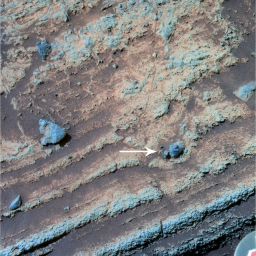

Volcanic Home Plate

Volcanic Home PlateSpirit took this false color image of an edge of Home Plate with its Pancam. It shows some of the evidence on which the science team is basing its hypothesis that the circular plateau was created from volcanic activity. The lower coarse-grained unit shows granular textures toward the bottom of the image and massive textures. A feature interpreted to be a "bomb sag," which is 4 centimeters across, is pointed out.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS/Cornell

After taking some pre-drive, Pancam images of targets atop Home, called Posole, Green Chile, and Flan, Spirit drove 24.83 meters (84.46 feet) up to Site 5 on Sol 1363 (November 3, 2007), finishing its day by taking post-drive image mosaics with the navigation cameras and Pancams. The next sol, the rover completed a survey of rock clasts with the Pancam and took a mosaic picture with the navigation camera, acquired some new images of the El Dorado dune field off in the distance with the Pancam, and after communicating with the Odyssey orbiter during its overhead pass, measured atmospheric argon with the APXS, in what is an ongoing study.

While Spirit took it easy on Sol 1365 (November 5, 2007) to recharge its battery, it got up bright and early the next sol to search for dust devils with the navigation camera. The roving field geologist then turned to Pecan Pie and brushed it with the RAT. It marked the first time this rover had used the new, two-sol brushing procedure that engineers had devised as a workaround to enable it to continue to use the device following the grind encoder failure. Considering the success, it was a good sol. But this rover didn't stop there. It continued working, taking pictures of the brushed target with the microscopic imager (MI) and analyzing its mineral composition with the APXS. It finished out the first week of the month by taking more images of the West Valley, completing its examination of Pecan Pie, and acquiring movie frames in search of dust devils with the navigation camera and full-color Pancam images of its tracks.

As the second week of November got underway, the pressure to get Spirit in position for winter intensified. With the dust inhibiting sunlight from reaching the rover's solar panels, the Sun to begin appearing lower on the northern horizon as the Martian season moves toward winter, and the number of good driving sols diminishing, Spirit was suddenly in something of a race against the clock to get to its winter haven. Its handlers were predicting its energy levels would decline from its then-current 325 watt-hours to about 260 watt-hours, the minimum safe power level for driving on level ground, by late December.

Already drawing more power for driving than can be provided by the solar arrays alone, Spirit's occasional day of rest and recharging became requisite after each sol of driving. That alone cut potential drive time in half. In addition, the rover wouldn't be driving on some weekend days, or during Thanksgiving or Christmas holidays. Yet, it is absolutely critical for the rover to reach the north face of Home Plate while it can access enough solar energy to survive. Playing it conservatively, the MER team moved up Spirit's desired estimated time of arrival (ETA) at Home Plate North. "We want the rover in its winter position, on a suitable, north-facing location at the north edge of Home Plate by Sol 1412 (December 23, 2007), before the Christmas holiday," Bruce Banerdt, of JPL, MER project scientist confirmed.

On Sol 1368 (November 8, 2007), Spirit conducted more studies of Pecan Pie, brushing the surface of the rock target with the RAT, acquiring stereo MI pictures of the brushed surface, and collecting nine hours of compositional data with the APXS. The rover also took another mosaic picture of the view of West Valley with the Pancam. During the ensuing sols, the rover ran more diagnostic tests on the RAT, took still more images of West Valley View and pictures of nearby ripples with the Pancam, analyzed Pecan Pie with the Mössbauer spectrometer, and acquired movie frames to record the progress of any dust devils that might be passing by. There were none.

Spirit stowed the robotic arm on Sol 1371 (November 11, 2007), took some final full-color pictures of Pecan Pie with the Pancam, then drove 17.5 meters (57.4 feet) toward Site 6 (also known as Site A) atop Home Plate. It took the usual pictures with the hazard avoidance camera just before and after ending the drive, as well as post-drive images with the navigation and Pancams.

After measuring the atmospheric dust by checking tau levels with the Pancam, Spirit spent Sol 1372 recharging its batteries, then on Sol 1373 (November 13, 2007) drove approximately 9 meters (30 feet) to Site 6. The rover wrapped up the second week of November conducting its routine atmospheric observations, snaping some full-color Pancam images of its tracks, and resting in a state of recharge.

Spirit roved on into the third week of November on Sol 1375 (November 15, 2007) and logged another 15 meters (49 feet) toward Site 7. The next sol, after measuring atmospheric dust with the Pancam, then monitoring dust on its mast, the rover recouped by recharging, as it was regularly doing now after every drive according to the new plan.

The rover acquired another mosaic picture of the West Valley on its Sol 1377 (November 17, 2007), as well as thumbnail images of the sky with the Pancam. It was slated to take off the following sol toward a hummock or elevated area in the distance of the area called Site 7. The drive on Sol 1378 (November 18, 2007) ended early, however, when Spirit's unusable, right front wheel stuck. At first, team members figured it had gotten caught up by a rock buried in the loose soil, though later analyses indicated it just may have gotten stuck in the morass of Martian soil "the soft, berm-like edge to this hollow," as Matijevic described it. Whatever ultimately turns out to be the case, when the wheel stuck, it caused the rover to turn and wheel around and wind up in a shallow crater.

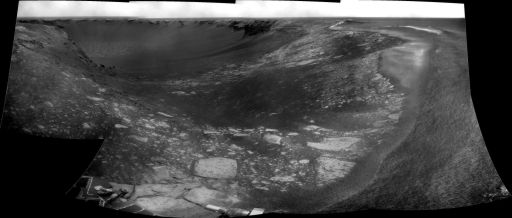

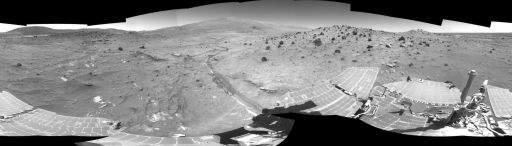

Spirit's last Martian winter haven, Low Ridge

Spirit's last Martian winter haven, Low RidgeSpirit acquired the images in this mosaic with the navigation camera on Sol 807 (April 11, 2006). Approaching from the east are the rover's tracks, including a shallow trench created by the broken front wheel. On the horizon, in the center of the panorama, is McCool Hill.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The pictures that Spirit took just before and after ending the drive with the hazard avoidance, navigation, and Pancams indicated Spirit was in trouble. During the ensuing 10 sols, the rover struggled, trying unsuccessfully to climb out of the crater and make the much-needed progress toward its winter haven. Subsequent pictures clearly showed Spirit was stuck, mucking around in this Martian soil. Despite it's predicament, the rover continued to taking pictures.

On Sol 1380 (Nov. 20, 2007), Spirit tried once again to escape, and again the drive faulted out when the rover experienced more than 90-percent slip after traveling 3.6 meters (11.8 feet). The team decided it should chill, but the rover completed a survey of rock clasts, took images of its tracks to look for compositional changes revealed by trenching, and scanned the Martian horizon with the Pancam before it said goodnight, reserving Sol 1381 (November 21, 2007) to power up with a recharge.

Spirit has collected a good bit of data from targets atop Home Plate, but so far there hasn't been any "real eyebrow-raising results lately," Banerdt reported. "So far the analyses we've been doing in the last couple of months have not come up with anything that's terribly striking. There are minor variations in some of the chemicals and people are looking at those. Perhaps there will be a story that will eventually come out of that. But there's nothing like the silica that just popped out, on the other side of Home, in the Silica Valley."

While Spirit's ground crew indulged in a day of feasting and relaxation, the rover spent Thanksgiving Day, its Sol 1382, monitoring dust on its Mini-TES, taking some Pancam images of a target called Sorbet near the center of Home, and acquiring movie frames in search of dust devils with the navigation camera. Good food and family aside, in the backs of probably every team member's mind was the fate of Spirit.

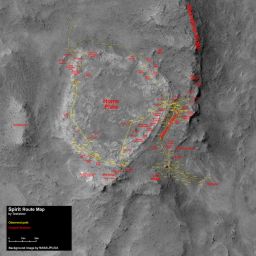

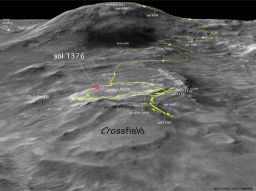

Home runs

Home runsWhile roving to Home Plate North where it will hunker down for winter, Spirit accidentally rolled into a dust-filled crater. After thrashing around for a week and a half, the rover finally emerged from the site now called Tartarus on Sol 1388 (Nov. 28, 2007) Spirit's goal now is to get to its winter haven before Christmas, so it can orient its solar panels to the north and take in as much sunlight "fuel" as possible. This map shows the rover's progress from July 2004 to November 2007. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS/UNM/UAz

At just two meters in diameter, "a little over a rover length in diameter," as Matijevic described it, "with a 10-centimeter (about 4-inch) lip," this crater is hardly a major feature. "But it is big enough to give us trouble," said Squyres. "If it had been big and obvious, we wouldn't have driven into it. It was insidious, because it was subtle enough that you could easily drive into without realizing it, but deep enough and bad enough to have trapped us."

"Because Spirit's right front wheel can't turn, it basically acts like a plow we have to drag through the sand and that just takes time," explained Matijevic. "The mechanization of the driving that we do with the absent right front wheel is that we're constantly looking for shifts in the position of the vehicle -– whether it's the orientation or whether in the lack of progress in moving forward. Those things are what terminated the drives over the past week or so."

So, Matijevic and his engineers changed the mode and temporarily altered the rules for driving Spirit. On Sol 1388 (November 28, 2007), the rover at last bolted free from the dust-filled crater the MER team quickly dubbed Tartarus. "We just named it," Squyres said late Thursday morning, November 29. "It means -- from Wikipedia: In classic Greek mythology, below Heaven, Earth, and Pontus, is Tartarus, or Tartaros . . . It is either a deep, gloomy place, a pit or abyss used as a dungeon of torment and suffering that resides within Hades or the entire underworld with Hades being the hellish component."

"Tartarus is a pit of torment and that's where we've been for the last week and a half on Spirit," Squyres said: "It was at least as bad as Tyrone, different from Purgatory. These craters tend to accumulate dust and soil. Dust will blow in and doesn't blow out as easily, so they tend to hold more loose debris than other spots do and that makes for bad traction. "When we realized what had happened and knew we had to start driving out of here, we started to drive backward. We have to drive backward with the [broken] right front wheel."

Actually, Spirit was facing a "triple-whammy" of a dilemma: a steep-sided hole in the ground, a busted wheel, and soft loose soil that makes for poor traction. "We just thrashed," said Squyres. "We made a complete mess of the soil and were digging in and digging in. The worst thing was that the two middle wheels dug in deep." On the rovers' rocker bogie suspension systems, the middle wheels and rear wheels on each side are on a bogie with a pivot point in the middle. "That means whenever the middle wheels go down, the rear wheels go up," he explained. "As we're driving backward, the middle wheels dug in and that popped the rear wheels off the ground completely. We popped a wheelie with both rear wheels. Both rear wheels were off the ground."

Spirit's bum wheel digs up bright soil

Spirit's bum wheel digs up bright soilAs Spirit headed eastward toward a hoped-for winter haven on McCool hill on Sol 788, its wheels stirred up an unusually large quantity of bright-colored, salty soil. For the full-resolution image, visit the Planetary Photojournal.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech /Cornell

"Think this through," Squyres continued. Indeed. And picture it. "You've got a six-wheeled vehicle, but only four wheels are in contact with the soil. Of those, one wheel is dead. So now we had a three-wheeled vehicle." Not to mention that the middle wheels don't steer and the right front wheel is dead weight. "And we're trying to climb an 11-12 degree slope in loose soil. We could basically go forward or backward. That's a bad situation. We couldn't steer. The risk in driving forward is that Spirit would dig deeper in -- and it was only card we had left to play effectively. We'd tried everything going backwards and it just wasn't working."

Spirit's Sol 1388 (November 28, 2007) drive forward was followed by "some very complex driving techniques to flatten out the bogies, get the rear wheels back on the ground," Squyres said. The rover then "did a clockwise turn in place" and tried backing out in a different direction. "Everything worked. All six wheels are back on rock right now. The drive went as far as we want it to go," he announced.

"The rover planners were just magnificent. It really was their finest hour I think," Squyres reflected. "If Wednesday night's drive plan hadn't work, I don't think we had too many other cards to play. By 5 a.m. Thursday morning, the team knew it didn't need any. The golf-cart sized rover had overcome a life-threatening challenge one more time and sent home picture to prove it was back out on bedrock.

Spirit in the Columbia Hills

Spirit in the Columbia HillsThis FX or manufactured image of Spirit in the Columbia Hills was produced using "Virtual Presence in Space" technology, developed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where the rovers were designed and built. This technology combines visualization and image-processing tools with Hollywood-style special effects to create a realistic image comprised of a photorealistic model of the rover and an image taken by Spirit with its navigation camera on Sol 438 (March 27, 2005). The size of the rover in the image is approximately correct and was based on the size of the rover tracks in the navigation-camera image. Dan Maas created the MER model; synthetic image by Koji Kuramura, Zareh Gorjian, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Spirit has no time to waste. It's only top priority now is to reach the north-facing slope of Home Plate. "We've picked the spot," Squyres said. "We don't want any eastward or westward tilt at all, but as much tilt to the north as we can possibly get it. The location we're looking at is pretty close to being centered on north edge of Home Plate, hanging off the northern side. It's this plateau with steep slope all the way around. It's not place we've driven onto before, but is a place we've imaged from off the north side."

"We've gotten some grids based on the imaging the rover did f the northern face around Sol 740, as it headed toward McCool Hill, so we have some pretty good relief grids of that area," elaborated Banerdt.

"We know the spot and we've done simulations," Squyres continued. "We think we'll get something close to 25 degrees of tilt. We're going to drive onto the steepest part of the slope on the northern most part and try to find the steepest spot we can."

Once Spirit gets to the Home Plate North area it will conduct, of course, a little bit of reconnaissance of the general area to pick the exact spot that has both the kinds of slopes the engineers are looking for and some level of scientific benefit for the scientists since the rover is likely to be hunkered down there fro more than 7 months. "When we're positioned, the consideration will be whether we have reasonable area underneath the vehicle and in front of the vehicle so that we can do some IDD activities at least over the course of part of the winter," said Matijevic. "It really doesn't matter whether we're parked in a front orientation pointing north or a back orientation pointing north. It's a matter of more how can we safely get to a tilt that's north facing so that we have our best chance of getting through the winter season and whether we can do something reasonable from that position."

Even with the best of positions and tilts, the MER team is anticipating that the rover will have to go to a low-power or even survival-only mode for a matter of not just sols but weeks. "We don't know until we get there, but that's the way things are looking right now," Banerdt said. "We're looking to spend substantial amount of time where we won't be able to do much science and communication will be limited." The rover and its team will be as prepared as it possibly can be. "We're doing the planning now to be able to go into that mode."

Unlike Opportunity, Spirit doesn't really have the option of going to a DeepSleep mode, "[p]artly because of the general temperature values we see here in the middle of winter," pointed out Matijevic. "It's actually somewhat warmer at the Meridiani Planum site and it was certainly warmer there during the dust storm, which was the summer season. In winter, the temperatures are quite a bit colder at Gusev where Spirit is."

The trouble with employing a DeepSleep strategy -- which they've done on Opportunity now countless times -- is, Matijevic said, "that essentially we put the vehicle in a state in which it cannot discharge from the batteries overnight. This is so we can minimize the energy drain on the batteries during this period. [The batteries are connected directly with the mission clock. The clock electronics is a continuous small energy drain even when the batteries are disconnected from other electronic loads.] But we also let the components inside the Warm Electronics Box (WEB) essentially ride with the diurnal temperatures we would see. These temperatures tend to make the components very cold as a result.

When is the Martian winter anyway?

When will winter begin this time in Mars southern hemisphere?

"It's totally arbitrary," says Steve Squyres, principal investigator for rover science. "You can view each season as [taking] one-quarter of the Martian year if you want, but the amount of power that we get on the rovers follows a kind of sinusoidal shaped curve. We're on the downward part of that curve now and it's going to flatten out [winter] and turn around sometime around June or so." The seasonal divides are arbitrary on Earth too. "On December 21,the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere, everyone in the news media says it's the first day of winter. It's actually the point at which the amount of sunlight is least, the shortest day of the year. From that point, you start moving back to summer as soon as winter has started."

Consider too that even though the day of least sunlight in the northern hemisphere comes on December 21, the coldest part of the year is generally in January and February. "There's a lag time, so even though you start getting more sunlight, because the system has so much mass, particularly the mass of the water in the oceans, it takes a while to respond," he explains. Therefore it's still cooling down in January and February even though you're actually getting more sunlight. "The point is, sums up Squyres, "the delineations of the start of fall or winter are completely arbitrary constructs that have no bearing in reality. You shouldn't worry about it."

Spirit took this panorama during the last Martian winter when it was parked at Low Ridge. It the largest panorama collected to date on the mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

The WEB is the insulated box that contains the batteries, the rover electronics module (REM), and the Mini-TES instrument. It essentially traps heat during the day and slowly dissipates it overnight, keeping the three components inside warm, as well as protected from the ambient conditions outside. When the temperature drops to -40 Celsius, the rover's heaters automatically come on. When the heater kick on, they drain considerable amounts of energy the rover won't have.

The brutally cold Martian winter temperatures are a particular concern for the batteries. "We know the batteries lose a certain amount of discharge capability when they get to -30 degrees C temperatures, so in order to preserve a certain amount of capability on the vehicle through this period we cannot use DeepSleep as an operation option on Spirit this winter," explained Matijevic.

So what then is the best way to keep the vehicle above that -40 degrees Celsius point when the survival heaters automatically turn on and begun sucking the power out of Spirit?

"The strategy is that we'll probably disable the heaters for the REM and the Mini-TES and let the survival heaters for the batteries work the way they normally do," said Matijevic. "We should be able to come through with about 160 watt-hours or a little less per day. That, plus keeping the batteries the way they normally are – with survival heating kicking on when it does -- means we'll come in around 140 to 150 watt-hours with the rest of the system."

"We've really done this same kind of analysis twice before for the prior winters," Matijevic continued. "The only difference here is that the energy levels are lower and to a certain extent there is uncertainty to what we'll see as temperature range. Disabling the other heaters plus all the other accommodations will probably mean the batteries won't see temperatures below -20 Celsius. The heaters activate around -17 Celsius. They kick on for a few cycles until it rises above -15 or so and they kick off. After we'd done the analysis, my own feeling is that there is a way to keep the vehicle going throughout this period. The benefit to the rovers built-in resilience is that, theoretically, it could almost hibernate until springtime or summer, then be started up again. "We should be okay. I believe Spirit will pull through."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

While JPL and Honeybee Robotics engineers worked in the rover test bed at the lab to figure out the cause of the latest "funky thing" going on with Opportunity's rock abrasion tool (RAT), the real rover spent Halloween checking for iron-bearing minerals in the light-toned rock ring that encircles the interior of Victoria Crater with the German-made Mössbauer spectrometer.

A new view of Cape Verde

A new view of Cape VerdeOpportunity took this false-color image of Cape Verde, one of the promontories that juts out from the walls of Victoria Crater, with its Pancam on Sol 1329 (Oct. 20, 2007), more than a month after it began its journey inside and just 9 sols shy of its second Martian birthday on Sol 1338 (Oct. 29, 2007). The rover used three Pancam filters, admitting light with wavelengths centered at 750 nanometers (near infrared), 530 nanometers (green) and 430 nanometers (violet) ont his image.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

Opportunity's planned operations with its RAT had failed on Sol 1334 (October 25, 2007), during both the calibration and grind-scan, the procedure for placing the instrument on the target. Data from the vehicle indicated unusual behavior in the encoder of the revolve motor. On Sols 1336 (October 27, 2007) and 1339 (October 30, 2007), the rover conducted more diagnostic tests that indicated the encoder for the actuator that makes the instrument revolve was functioning as expected. The encoder for the actuator that causes the RAT to grind, on the other hand, has not been functioning since it failed on Sol 1045 (January 1, 2007). Based on the latest test results, the team decided Opportunity would retry the grind-scan procedure on Sol 1341 (November 1, 2007).

Throughout the month, Opportunity, like Spirit, maintained a regular communication schedule, with morning uplinks directly from Earth via its high-gain antenna, and evening downlinks to Earth via the Odyssey orbiter at UHF frequencies, in addition to its routine atmospheric measurements and surveys of the horizon with the panoramic camera (Pancam).

Other than that, the rover spent virtually the entire month of November checking out Smith, a target in second or middle layer of the tri-layered ring, taking mosaic pictures of Lyell with the Pancam, a target on the third layer, located about two meters further into the crater. It also began an imaging campaign of Cape Verde and Cabo Frio, two of the cliff faces that form the Victoria's scalloped rim. While the light-toned rock ring would remain the focus of the rover's research for some weeks to come, the subtle stratigraphy that began turning up in the high-resolution images streaming down through the Deep Space Network (DSN) to JPL this month started turning more and more heads.

On Sol 1341 (November 1, 2007), Opportunity followed commands for the grind-scan procedure for placing the RAT on a target, acquired full-color images of a rock target called Oppel, and watched the sky for clouds with its navigation camera. After communicating with Odyssey, the rover turned the alpha-particle X-ray (APXS) skyward and measure atmospheric argon. The next sol, it turned its attentions to imaging Cape Verde, then went into DeepSleep mode. The sol after that, Sol 1343 (November 3, 2007), the rover conducted more diagnostic tests of the RAT and collected more compositional data from Smith with the Mössbauer spectrometer.

As the week wore on, Opportunity ran more diagnostic tests on the RAT and continued its study of Smith by acquiring more compositional data with the Mössbauer and taking some full-color Pancam images. Additionally, the rover took Pancam images of Lyell and other rock targets, including ones named Jin and Gressly, then acquired thumbnail images of the sky and measured atmospheric argon with the APXS.

Meanwhile, the team working on Opportunity's RAT issue had determined the RAT encoder that operates the revolve motors, which make the brush rotate, was lost. Normally, the RAT software monitors the safe operation of the grind or brush using the two encoders, which detect stalls that can occur during grinding and encoding. In the event of a stall, the encoders measure the z-axis position, the point where the RAT contacts the rock surface. Now Opportunity's RAT had lost both those encoders. The engineers and scientists working in test beds and computer-sequencing rooms had devised a workaround that relied on current limits and contact switches to know when the RAT's grind teeth come into contact with a rock surface and on Sol 1347 (November 7, 2007), Opportunity successfully completed a new, seek-scan procedure with the RAT. With this "workaround," the rover locates a rock surface by simultaneously spinning its grind teeth and wire brush while extending toward the rock surface.

During another test, the rover was mistakenly commanded to rotate the brush in the wrong direction. As a result, the brush spun around the wrong way and bent outward, perpendicular to the plane of rotation. Following first assessment of the damage, the science team directed the rover on Sol 1348 (November 8, 2007), to retract the RAT 1 millimeter and brush the surface of Smith. The brushing proceeded as planned and in addition to completing an encoder-less brush of the surface of Smith, the rover acquired microscopic imager (MI) pictures of the brushed surface, and analyzed its mineral content with the APXS.

Rock on, Victoria

Rock on, VictoriaOpportunity took this image of light-colored rocks inside Victoria Crater on Sol 1341 (Nov. 1, 2007), where it is studying a tri-layered rock ring that encircles the massive hole in the ground. The MER scientists thinkthese rocks may be representative of the original surface before a meteor formed the crater and splattered debris onto it.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

In the sols that followed, Opportunity spent much of its time snapping pictures like a just-landed tourist. The rover took mosaic images with its Pancam of Cabo Frio, Cape Verde from below, of Smith and a layered rock target known as Brongniart, and a mosaic of images of Lyell. It also took some full-color Pancam images of the freshly-brushed surface of Smith, placed the Mössbauer spectrometer on the brushed Smith target to measure the abundance and composition of any iron-bearing minerals, measured argon in the Martian atmosphere with the APXS, and conducted more diagnostic tests of the RAT.

The rover finished out the second week of November continuing its Mössbauer analysis of Smith, taking more pictures of Cape Verde and Cabo Frio at different times of day, as well as spot images of the sky with the Pancam, an APXS analysis of the external capture magnet, conducting still more diagnostic tests of the RAT, and on Sol 1354 (November 14, 2007) testing UHF communications with the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) in preparation for next year's arrival of the Phoenix lander.

During the third week of November, Opportunity did more Mössbauer analysis of Smith, collecting a total of 47 more hours worth of data, and spent quality time taking super-resolution images of Cape Verde and Cabo Frio. It also filled out its workday, taking spot images of the sky and surveys of the horizon with the Pancam, searching the sky for clouds with the navigation camera, and measuring its attitude by looking at the Sun.

As it turned out, the images of Smith following the post-bent brush incident workaround brushing indicated that the brush had gouged into the target. "When we did this brush at the Smith location, we actually ground in a little couple of donut shapes into the rock there, instead of just brushing a nice clean surface," Banerdt explained. There is some thinking now that the RAT brush may not be useable in the way it was meant to be used and may be permanently bent.

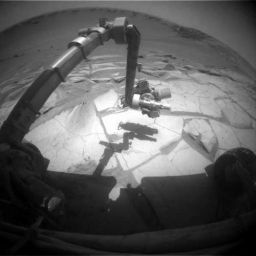

Smith

SmithOpportunity took this image with its front hazard camera on Sol 1366 (Nov. 26, 2007) as it conducted tests with its rock abrasion tool (RAT). The rover is preparing to grind into Smith, the second or middle layer of the tri-layer rock ring that encircles the interior of Victoria Crater.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The unexpected mess at Smith instigated the team to have Opportunity reach for nearby clean spot of rock surface on this layer, a spot now known as Smith2. "When the brush went backward, rather than clean up the Smith RAT hole, we decided start over basically at Smith2," confirmed Squyres. "We identified a second target at Smith that is just a few tenths-of-centimeters away, so we're just moving the arm. Banerdt expounded. "We don't have to reposition the rover itself."

On Sol 1359 (November 19, 2007), Opportunity made the reach – and switch to Smith2. While the rover was taking close-up picture mosaics of the new target on the rock layer with the MI, however, a joint in Opportunity's robotic arm (Joint 1) that controls azimuth (left-right motion) stalled during the acquisition of microscopic images of the un-ground surface of Smith2. Instead of finishing the imaging, the rover acquired 12 hours worth of compositional data from the Martian atmosphere with the APXS. The next morning, the rover took care of some basic business, calibrating the Pancam by taking images in darkness, scanning the sky for clouds using the navigation camera, monitoring dust on the rover mast, and taking spot images of the sky. And on Sol 1360 (November 21, 2007), Opportunity acquired a mosaic of images of Paolo's Pan with the Pancam then calibrated the camera by taking images in darkness.

During tests of the RAT on the analogue test bed rover, engineers discovered that unbending the brush on Opportunity's RAT may not be possible. Instead of brushing the surface of a new rock target known as Smith2, rover handlers opted to proceed directly to grinding the rock surface in coming sols. The engineers, meanwhile, refined their alternate strategy "to still use what appear to be good motors on these devices and yet achieve roughly the same sort of affect," Matijevic reported Wednesday. "We'll probably see some evidence of this in the next week or so as we implement these processes on Mars."

"We've gone through a very extensive test program on the ground using the RAT with these failed encoders to do what we call an open-loop grind and we think we've got that problem all squared away," Squyres elaborated yesterday. "If the grind scan we sent up Wednesday goes well, we'll be planning the RAT grind into Smith2 soon, maybe this weekend." Once that assignment is finished and the rover has acquired the measurements needed in that RAT hole, Opportunity will rove deeper into the crater just a couple of meters to Lyell, as planned.

Scientifically, the recent data that Opportunity has sent home from Victoria's rock ring is still being analyzed and data on Smith is, as mentioned above, still being collected. But it would appear that Opportunity has found anything particularly unusual or unexpected. "Steno turned out to be extremely sulfur-rich," Squyres informed. "It's one of the most sulfate rich targets we've ever seen. Interesting, but not surprising because all along the most sulfate-rich stuff we've found is the stuff at the top of the section. The interesting thing is going to come when we can compare Smith to Steno, Smith to Lyell, Lyell to Smith to see if we can tell what's going on." Squyres isn't yet willing to speculate, not surprisingly, on what they think they may see or what it will mean. "We'll just wait until Mars tells us."

For all the MER Updates, go to: http://www.planetary.org/explore/space-topics/space-missions/mer-updates/

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth