Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 17, 2007

MESSENGER update

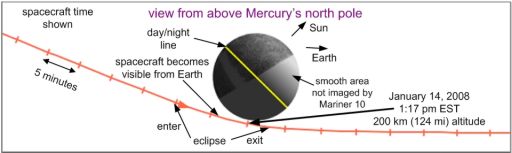

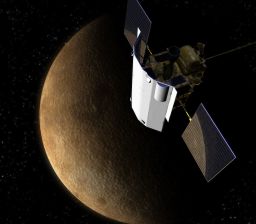

The MESSENGER spacecraft is headed toward its first of three flybys of Mercury, on January 14, 2008. (It will take three flybys to match its orbital geometry close enough to Mercury's so that it will be able to enter Mercury orbit on March 18, 2011.) It is now in a pretty tight orbit around the Sun, and on September 1, it will reach its closest perihelion yet, passing through a minimum distance to the Sun of only 0.33 Astronomical Units. Being three times closer to the Sun than Earth means that the Sun now feels nine times stronger to MESSENGER than it does to the Earth-orbiting spacecraft that MESSENGER left behind three years ago.

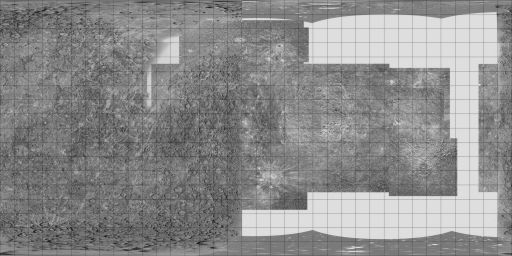

Louise Prockter is an outer planets scientist who's also working on the MESSENGER MDIS camera team, and during the conference she invited me to take a look at a preliminary imaging plan for the January flyby. The three-flyby plan is strangely similar to the mission of Mariner 10, which flew by Mercury three times in 1974 and 1975. Because of Mercury's spin-orbit resonance, Mariner 10 saw the same hemisphere, with pretty much the same lighting geometry, on all three encounters, which means that fully half of Mercury has never been seen by spacecraft. MESSENGER, too, will see the same hemisphere sunlit on all three of its flybys, but whether due to good fortune or good planning or some combination of the two, the MESSENGER hemisphere will be almost exactly that side of Mercury that was not seen by Mariner 10.

The post-flyby sequence starts with the highest-resolution mosaic centered on the equator, then as MESSENGER recedes, it shoots full-planet mosaics. After receding a bit more the imaging switches to color views; flash-flash-flash, MDIS grabs 11 images of the same spot through each of its color filters before moving to the next spot. And, because none of the other instruments can operate, every time MDIS finishes a global mosaic, it starts over with another one. Louise told me that they want to make absolutely totally sure they get this view of the unseen side; it's one of their major mission success criteria, and one they can accomplish long before they go into orbit. She said she didn't know how many of the mosaics they'd really be able to do, but they'll do as many as data volume allows. At some point they switch from shooting global mosaics to a narrow-angle, single-color movie of the departure; it will start with Mercury more than filling the field of view, and end with it appearing as a small ball in the center.

Louise says that the current plan is for the radio science team to be "doing something" for the couple of days following the encounter, so image data won't start returning to Earth until after that, and that the order in which it will be returned has something to do with the compression being performed onboard the spacecraft.

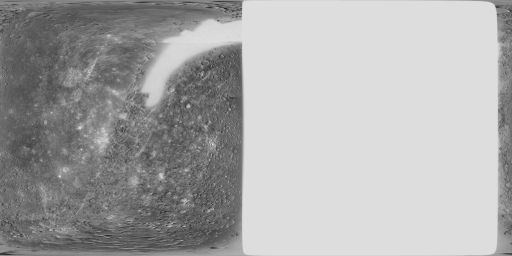

That hemisphere of Mercury is, I think, the largest surface in the solar system that hasn't been seen by a spacecraft (at 5,000 kilometers in diameter, half of Mercury is actually bigger than, say, all of Pluto or Eris, which are about 2,300 and 2,400 kilometers in diameter, respectively). However, I should point out that that hemisphere isn't actually completely unknown. Far from it, in fact. Here's a recent map that combines the Mariner 10 data with radar images produced by Arecibo.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth