Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 14, 2007

Ices, Oceans, and Fire: Monday afternoon: New Horizons at Jupiter

Monday afternoon John Spencer gave a lengthy talk about the New Horizons encounter with Jupiter. I've posted extensively on this in the past: approaching Jupiter; Jupiter rotating; full frame on Jupiter; Jupiter cloud motion; Io erupting; Alice's view; retreating view of Io and Europa; early science results; Europa images; Tvashtar movie; etc, etc, etc. And in fact John Spencer posted here too, about approaching Jupiter and Io's eruptions. So I'll try to keep to things that were new to me.

John went over New Horizons' trajectory to Pluto, and mentioned that during the long cruise they will actually be doing a little bit of science on Uranus and Neptune. New Horizons will be way too far away to resolve either planet, but will be able to measure each planet's brightness at a variety of phase angles. From Earth, we pretty much only see Uranus and Neptune almost fully lit by the Sun (that is, from very low phase angles); New Horizons will get much higher phase views.

He mentioned that the goals for the Jupiter encounter were fourfold. First in importance was the gravity assist; second was for the science team to undergo a stress test ("at this," John remarked, "we were very successful.") Third was to calibrate the instruments; science came in last, but they still managed to accomplish a lot.

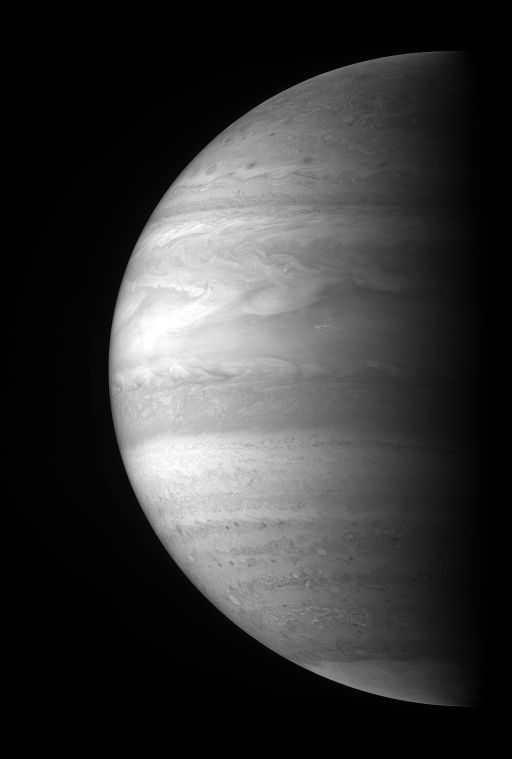

He showed some images from the Ralph MVIC multispectral imager that I hadn't seen before. Ralph could not be used much at Jupiter because it was too sensitive for the bright lighting conditions there; the detectors would be totally saturated, even with the shortest possible exposures. But there was an exception: one of the filters is a narrow-band one in a wavelength in which methane strongly absorbs light. Because Jupiter has a lot of methane in its atmosphere, and methane absorbs so much of the light, Ralph was able to capture a 3,000-pixel portrait of Jupiter in this methane band. Turns out the images was released on the mission website in May; I just hadn't noticed it before. Here it is in all its glory.

NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI

New Horizons view of Jupiter in a methane band

New Horizons captured this incredibly detailed view of Jupiter's high-altitude, methane-rich clouds on Febriary 28, 2007, near the spacecraft's closest approach. The image was taken at a near-infrared wavelength of 890 nanometers. This wavelength of light that is strongly absorbed by methane gas.The image reveals a range of diverse features. The south pole is capped with a haze of small particles probably created by the precipitation of charged particles into the polar regions during auroral activity. Just north of the cap is a well-formed anticyclonic vortex with rising white thunderheads at its core. Slightly north of the vortex are the tendrils of some rather disorganized storms and more pinpoint-like thunderheads. The dark "measles" that appear a bit farther north are actually cloud-free regions where light is completely absorbed by the methane gas and essentially disappears from view. The wind action considerably picks up in the equatorial regions where giant plumes are stretched into a long wave pattern. Proceeding north of the equator, cirrus-like clouds are shredded by winds reaching speeds of up to 180 meters per second (400 miles per hour), and more pinpoint-like thunderheads are visible. Although some of the famous belt-and-zone structure of Jupiter's atmosphere is washed out when viewed at this wavelength, the relatively thin North Temperate Belt shows up quite nicely, as does a series of waves just north of the belt. The north polar region of Jupiter in this image has a mottled appearance, and the scene is not as dynamic as the equatorial and south polar regions.

NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI

Glowing Tvashtar

New Horizons captured this view of a crescent Io on March 1, 2007, 19 hours after its losest approach to Jupiter. The dayside is deliberately overexposed to bring out faint details in the plumes and on the moon's night side. The plume erupting 330 kilometers from the top of the globe is from the volcano Tvashtar. The plume is lit both by sunlight and by Jupitershine. Beneath the plume is the incandescent glow of hot lava.He discussed the cool Io eclipse images too:

NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI

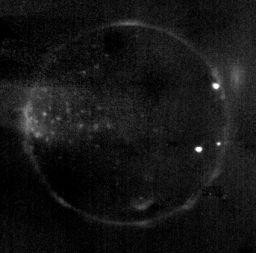

Io in eclipse

As New Horizons sailed past Jupiter on February 27, 2007, it watched Io pass in to Jupiter's shadow. Without the Sun illuminating the surface, New Horizons could keep its shutter open for a very long time, capturing the glow of hot spots and aurorae on Io's surface and atmosphere. The three brightest spots are from the incandescent glow of hot lava erupting from volcanoes: Pele and Reiden (south of the equator), and a previously unknown volcano near 22°N, 233°W. The disk is outlined by an auroral glow, produced by the interaction of Europa's thin atmosphere with the intense magnetic field of Jupiter. A spot at 2 o'clock is a cloud of atmosphere that is somehow levitating 330 kilometers above the surface. On the left side of the disk is a spotty region on the side of Io that faces Jupiter.Looking at the famous Tvashtar plume movie:

NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI

Tvashtar in motion

In this amazing animation from the New Horizons flyby of Jupiter, the 300-kilometer-high plume erupting from Io's Tvashtar volcano is visibly in motion, its fountains of lava spraying up, out, and back down to the Ionian surface. New Horizons captured the motion fortuitously; the images were part of an observation of the ring system designed to search for structures in the rings, and because Io was close by the science team planned the ring images to encompass Io in the same frame. The animation contains five images taken over an eight-minute span of time beginning at 23:50 UT on March 1, 2007.He noted that all of their temperature measurements indicated that the lavas were likely of ordinary basaltic composition; they see no evidence for higher temperatures requiring exotic lava compositions.

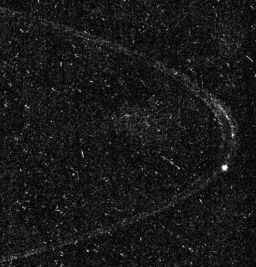

Commenting on the satellite search, he said "We did not find any satellites that we believe yet, down to 1 kilometer in size. But we found something more interesting. We found two ring clumps confined to a narrow bright arc. At first Mark Showalter thought these were collisional remnants from a recent collision, but we do not see them brightening at high phase angle" as they would expect from a collision, which would have produced dust. "So they may be confined arcs like at Neptune or in Cassini's G ring, related to orbital resonances with Metis."

NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI

Clumps following Adrastea

One of the surprising discoveries from New Horizons' encounter with Jupiter was three clumps in the main rings following the tiny moon Adrastea (16 kilometers in diameter). The discovery of the clumps was made by Mark Showalter, who had designed the imaging sequence to search for previously undiscovered moons in the rings.

NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI

Io and Europa

Io and Europa shone as jewel-toned crescents to the MVIC imaging spectrometer on New Horizons as the spacecraft sped away from Jupiter at 10:34 UT on March 2, 2007. Europa appears to be the larger of the two, but that's an optical illusion because of their different distances from the spacecraft: larger Io (3,630 kilometers in diameter) is 4.6 million kilometers from New Horizons, while smaller Europa (3,122 kilometers in diameter) is closer at 3.8 million kilometers away. When this image was taken, Io was on the far side of Jupiter from New Horizons, while Europa was closer to Jupiter than New Horizons. Being on the far side of Jupiter, Io's night side is lit by sunlight reflected off of Jupiter's cloud tops. Europa's night side is not, because the side of Europa that is receiving reflected light from Jupiter is the side that is facing away from New Horizons.Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth