Marc Rayman • Oct 30, 2015

Dawn Journal: A Bounty of Data

Dear Exuldawnt Readers,

Dawn has completed another outstandingly successful campaign to acquire a wealth of pictures and other data in its exploration of dwarf planet Ceres. Exultant residents of distant Earth now have the clearest and most complete view ever of this former planet.

The stalwart probe spent more than two months orbiting 915 miles (1,470 kilometers) above the alien world. We described the plans for this third major phase of Dawn’s investigation (also known as the high altitude mapping orbit, or HAMO) in August and provided a brief progress report in September. Now we can look back on its extremely productive work.

Each revolution, flying over the north pole to the south pole and back to the north, took Dawn 19 hours. Mission planners carefully chose the orbital parameters to coordinate the spacecraft’s travels with the nine-hour rotation period of Ceres (one Cerean day) and with the field of view of the camera so that in 12 orbits over the lit hemisphere (one mapping “cycle”), Dawn could photograph all of the terrain.

In each of six mapping cycles, the robot held its camera and its infrared and visible mapping spectrometers at a different angle. For the first cycle (Aug. 17-26), Dawn looked straight down. For the second, it looked a little bit behind and to the left as it completed another dozen orbits. For the third map, it pointed the sensors a little behind and to the right. In its fourth cycle, it aimed ahead and to the left. When it made its fifth map, it peered immediately ahead, and for the sixth and final cycle (Oct. 12-21) it viewed terrain farther back than in the third cycle but not as far to the right.

The result of this extensive mapping is a very rich collection of photos of the fascinating scenery on a distant world. Think for a moment of the pictures not so much from the standpoint of the spacecraft but rather from a location on the ground. With the different perspectives in each mapping cycle, that location has been photographed from several different angles, providing stereo views. Scientists will use these pictures to make the landscape pop into its full three dimensionality.

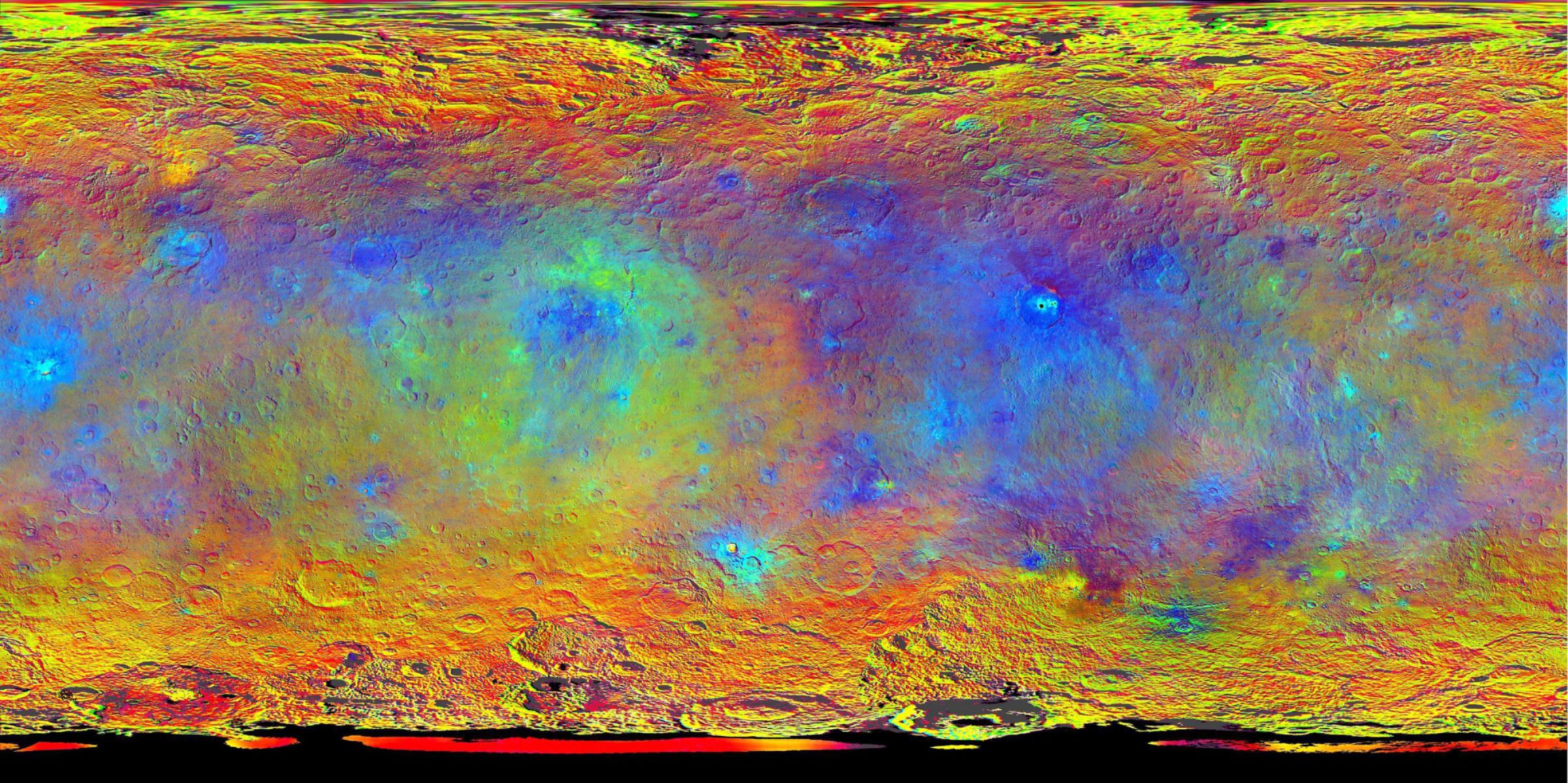

Dawn’s reward for these two months of hard work is much more than revealing Ceres’ detailed topography, valuable though that is. During the first and fifth mapping cycles, it used the seven color filters in the camera, providing extensive coverage in visible and infrared wavelengths.

In addition to taking more than 6,700 pictures, the spacecraft operated its visible and infrared mapping spectrometers to acquire in excess of 12.5 million spectra. Each spectrum contains much finer measurements of the colors and a wider range of wavelengths than the camera. In exchange, the camera has sharper vision and so can discern smaller geological features. As the nerdier among us would say, the spectrometers achieve better spectral resolution and the camera achieves better spatial resolution. Fortunately, it is not a competition, because Dawn has both, and the instruments yield complementary measurements.

Even as scientists are methodically analyzing the vast trove of data, turning it into knowledge, you can go to the Ceres image gallery to see some of Dawn’s pictures, exhibiting a great variety of terrain, smooth or rugged, strangely bright or dark, unique in the solar system or reminiscent of elsewhere spacecraft have traveled, and always intriguing.

Among the questions scientists are grappling with is what the nature of the bright regions is. There are many places on Ceres that display strikingly reflective material but nowhere as prominently as in Occator crater. Even as Dawn approached Ceres, the mysterious reflections shone out far into space, mesmerizing and irresistible, as if to guide or even seduce a passing ship into going closer. Our intrepid interplanetary adventurer, compelled not by this cosmic invitation but rather by humankind’s still more powerful yearning for new knowledge and new insights, did indeed venture in. Now it has acquired excellent pictures and beautiful spectra that will help determine the composition and perhaps even how the bright areas came to be. Thanks to the extraordinary power of the scientific method, we can look forward to explanations. (And while you wait, you can register your vote here for what the answer will be.)

Scientists also puzzle over the number and distribution of craters. We mentioned in December the possibility that ice being mixed in as a major component on or near the surface would cause the material to flow, albeit very slowly on the scale of a human lifetime. But over longer times, the glacially slow movement might prove significant. Most of Ceres’ craters are excavated by impacts from some of the many bodies that roam that part of the solar system. Ceres lives in a rough neighborhood, and being the most massive body between Mars and Jupiter does not give it immunity to assaults. Indeed, its gravity makes it even more susceptible, attracting passersby. But once a crater is formed, the scar might be expected to heal as the misshapen ground gradually recovers. In some ways this is similar to when you remove pressure from your skin. What may be a deep impression relaxes, and after a while, the original mark (or, one may hope, Marc) is gone. But Ceres has more craters than some scientists had anticipated, especially at low latitudes where sunlight provides a faint warming. Apparently the expectation of the gradual disappearance of craters was not quite right. Is there less evidence of flowing ground material because the temperature is lower than predicted (causing the flow to be even slower), because the composition is not quite what was assumed, or because of other reasons? Moreover, craters are not distributed as would be expected for random pummeling; some regions display significantly more craters than others. Investigating this heterogeneity may give further insight into the geological processes that have taken place and are occurring now on this dwarf planet.

Dawn’s bounty from this third major science campaign includes even more than stereo and color pictures plus visible and infrared spectra. Precise tracking of the spacecraft as it moves in response to Ceres’ gravitational pull allows scientists to calculate the arrangement of mass in the behemoth. Performing such measurements will be among the top three priorities for the lowest altitude orbit, when Dawn experiences the strongest buffeting from the gravitational currents, but already the structure of the gravitational field is starting to be evident. We will see next month how this led to a small change in the choice of the altitude for this next orbit, which will be less than 235 miles (380 kilometers).

The other top two priorities for the final mission phase are the measurement of neutron spectra and the measurement of gamma ray spectra, both of which will help in establishing what species of atoms are present on and near the surface. The weak radiation from Ceres is difficult to measure from the altitudes at which Dawn has been operating so far. The gamma ray and neutron detector (GRaND) has been in use since March 12 (shortly after Dawn arrived in orbit), but that has been to prepare for the low orbit. Nevertheless, the sophisticated instrument did detect the dwarf planet’s faint nuclear emissions even in this third orbital phase. The signal was not strong enough to allow any conclusions about the elemental composition, but it is interesting to begin seeing the radiation which will help uncover more of Ceres’ secrets when Dawn is closer.

To scientists’ great delight, one of GRaND’s sensors even found an entirely unexpected signature of Ceres in Dawn’s second mapping orbit, where the spacecraft revolved every 3.1 days at an altitude of 2,700 miles (4,400 kilometers). In a nice example of scientific serendipity, it detected high energy electrons in the same region of space above Ceres on three consecutive orbits. Electrons and other subatomic particles stream outward from the sun in what is called the solar wind, and researchers understand how planets with magnetic fields can accelerate them to higher energy. Earth is an example of a planet with a magnetic field, but Ceres is thought not to be. So scientists now have the unanticipated joy not only of establishing the physical mechanism responsible for this discovery but also determining what it reveals about this dwarf planet.

Several times during each of the six mapping cycles, Dawn expended a few grams of its precious hydrazine propellant to rotate so it could aim its main antenna at Earth. While the craft soared high above ground cloaked in the deep black of night, it transmitted some of its findings to NASA’s Deep Space Network. But Dawn conducted so many observations that during half an orbit, or about 9.5 hours, it could not radio enough data to empty its memory. By the end of each mapping cycle, the probe had accumulated so much data that it fixed its antenna on Earth for about two days, or 2.5 revolutions, to send its detailed reports on Ceres to eager Earthlings.

Following the conclusion of the final mapping cycle, after transmitting the last of the information it had stored in its computer, the robotic explorer did not waste any time gloating over its accomplishments. There was still a great deal more work to do. On Oct. 23 at 3:30 p.m., it fired up ion engine #2 (the same one it used to descend from the second mapping orbit to the third) to begin more than seven weeks of spiraling down to its fourth orbit. (You can follow its progress here and on Twitter @NASA_Dawn.) Dawn has accomplished more than 5.4 years of ion thrusting since it left Earth, and the complex descent to less than 235 miles (380 kilometers) is the final thrusting campaign of the entire extraterrestrial expedition. (The ion propulsion system will be used occasionally to make small adjustments to the final orbit.)

The blue lights in Dawn mission control that indicate the spacecraft is thrusting had been off since Aug. 13. Now they are on again, serving as a constant (and cool) reminder that the ambitious mission is continuing to power its way to new (and cool) destinations.

Dawn is 740 miles (1,190 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 2.91 AU (271 million miles, or 436 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,165 times as far as the moon and 2.93 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 48 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

3:00 p.m. PDT October 30, 2015

P.S. While the spacecraft is hard at work continuing its descent tomorrow, your correspondent will be hard at work dispensing treats to budding (but cute) extortionists at his front door. But zany and playful as ever, he will expand his delightful costume from last year by adding eight parts dark energy. Trick or treat!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth