Casey Dreier • Oct 30, 2014

The Antares Accident: Whose Rocket Was It?

An uncrewed rocket built and launched by Orbital Sciences exploded during a routine servicing mission to the International Space Station on Tuesday. Fortunately, no one was hurt. The payload was completely destroyed.

CNN was among many news sources that reported the mishap with an important (and incorrect) use of language. Here’s an example, can you spot the error?

An unmanned #NASA rocket exploded upon launch. There was no indicated loss of life, @NASA said http://t.co/8ebWSprrUW pic.twitter.com/DU2YKmQ0Xt

— CNN (@CNN) October 28, 2014Savvy readers know that the Antares rocket is not a NASA rocket—it’s owned by the Orbital Sciences company. NASA pays Orbital to deliver supplies to the International Space Station, and NASA itself has no ownership of the rocket or the intellectual property related to it.

Casting Antares as a NASA rocket, though, generates predictable responses like this:

@CNN @NASA Good lord, our government can't do a damn thing right. Glad no one was injured.

— Eileen (@mylifeback) October 28, 2014Criticizing NASA for the Antares’ mishap would be like blaming Amazon.com for the crash of a FedEx truck: NASA was the customer here. Would this person’s head explode if they knew Orbital Sciences was founded by Harvard Business School graduates and is publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange (as ORB)? Maybe. But that’s not why I’m writing this post today.

Instead, I think this provides a great opportunity to explore what it means for Antares to be rocket owned by a private company. After all, the Atlas V, which launched Curiosity to Mars, is built by a joint venture of two private companies—Lockheed-Martin and Boeing—but few people would consider that in the same class. Likewise, Boeing is the prime contractor on NASA’s Space Launch System, which I would very much consider a “NASA rocket.” So what makes Antares different?

In a word: contracts

Ok, please don’t stop reading. It’s often the case that some of the most important developments in space exploration happen because of boring-sounding policy decisions. But understanding this is crucial to understanding the consequences of Tuesday’s disaster, i.e. why it’s worse for Orbital than for NASA.

For the most part, when NASA needs hardware, the aerospace industry will help develop and build it. In very basic terms, NASA will set forth some very specific design requirements, have significant and detailed project oversight, generally assumes responsibility for cost overruns, and guarantees a pre-determined profit for the company. NASA ends up owning the hardware after it’s built and also acquires much of the intellectual property rights associated with it. This is a common type of government contract known as cost-plus.

NASA took a very different strategy when it came to the problem of resupplying the space station after the retirement of the Space Shuttle. Instead of contracting hardware, it wanted to contract a service. NASA said (and this is very simplified): “We’ll pay you ferry stuff to the station. How you do it is up to you as long as you convince us it will work.” For those of you keeping track at home, this was the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) competition.

Instead of creating detailed requirements for the spacecraft and rockets, NASA stuck to big picture requirements: how much mass it wanted delivered to the ISS, how often, what it needed to come back to Earth, etc. The companies answering this call from NASA were left to develop their own specifics on how they would achieve these goals. NASA would provide assistance, both financial and technical, as a partner in the development effort, but not assume ownership of the hardware or of the resultant intellectual property.

Antares, an Orbital Sciences Rocket

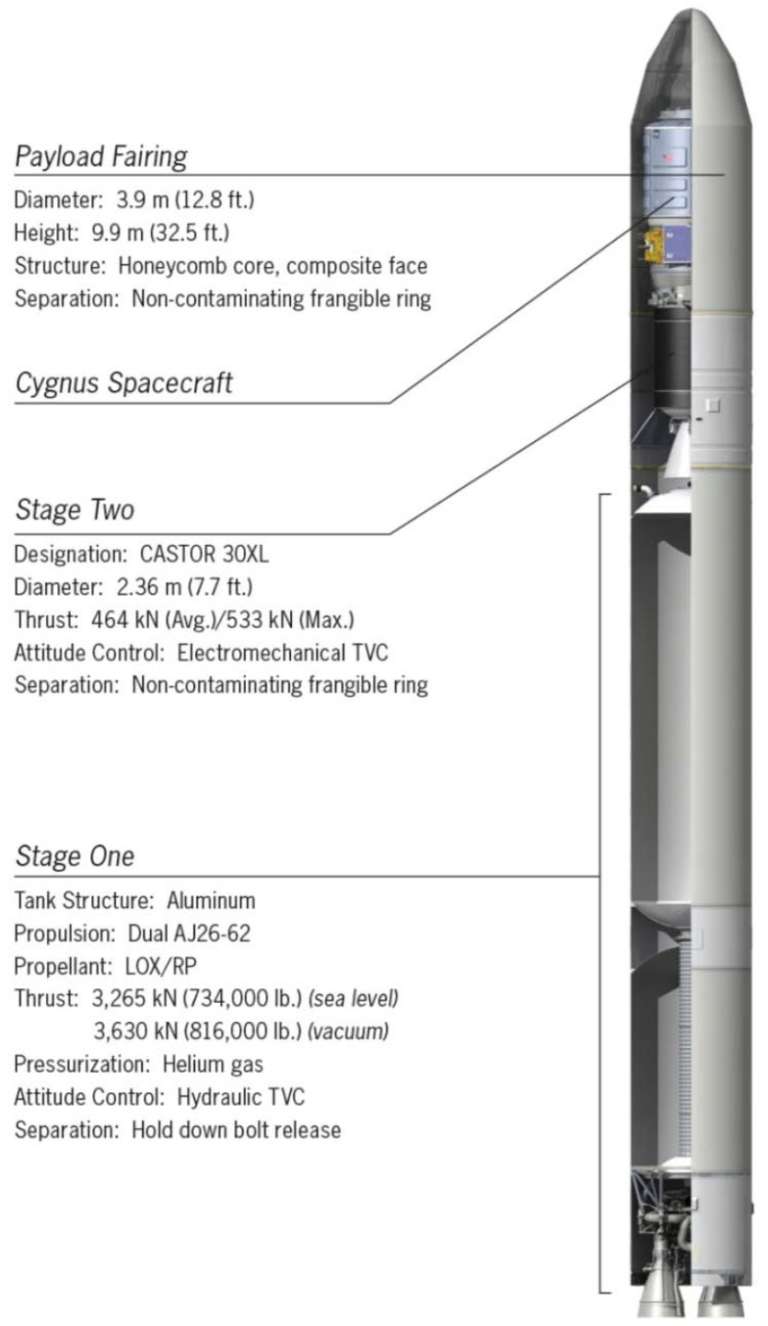

NASA ultimately decided upon two companies to provide resupply services to the International Space Station: SpaceX and Orbital Sciences, the latter of which proposed the Antares medium-lift rocket to carry the Cygnus cargo ship.

Over the course of five years (2008 - 2013) NASA supported Orbital in the development of Antares and Cygnus. Orbital passed a series of pre-defined milestones that unlocked further development money from NASA, though the company ultimately invested approximately $590 million of its own money developing the Antares and Cygnus. NASA chipped in $288 million for early development plus an additional $1.9 billion contract for eight resupply missions to be completed by 2016.

Orbital’s approach to the ISS resupply problem was to design a rocket that would utilize existing, proven technology from a variety of subcontractors in order to minimize costs (this is in marked contrast to SpaceX, which builds many of its components for the Falcon 9 in-house in its own attempt to save money). Orbital assembles the Antares rocket and Cygnus spacecraft using hardware from manufacturers around the world: Cygnus is built in Italy, the Antares’ first stage was developed and is built in Ukraine, and the first stage engines (the AJ-26s) are upgraded-but-still-Soviet-era hardware supplied by California-based Aerojet Rocketdyne.

The system had proved successful until the most recent flight, which would have been the third of the eight contracted resupply missions to the space station and the fifth successful flight of the rocket.

Look at this from the money perspective, and it clarifies even more. Orbital's contract is for eight successful resupply missions to the ISS; they are still on the hook to provide all of them, despite the failure of this mission. Frank Culbertson, Executive Vice President and General Manager of Orbital’s Advanced Programs Group, stated that the company lost over $200 million in hardware in Tuesday’s disaster. This does not include the damages to the launch site or the 17% drop in Orbital Sciences’ stock price on Wednesday. It’s their rocket to profit with, but they also assume a significant amount of financial risk in the effort.

Loaded Language

The Antares rocket wouldn’t exist if NASA didn’t need to resupply the ISS and didn’t provide billions of dollars worth of development money and supply contracts. Antares also has no other customers besides NASA (though there’s nothing stopping Orbital from selling launch services, like SpaceX does, to anyone it pleases within the constraints of U.S. law). So in a sense, Antares is a rocket for NASA, but it’s still not NASA’s rocket.

However, to the majority of people out there, NASA is anything space-related. The agency is assigned responsibility when things go wrong whether or not the contracting agreements say otherwise. NASA’s past successes are so ingrained in the culture that it’s nearly impossible to separate space from the space agency (SpaceX is a notable exception to this, though that’s thanks to some brilliant marketing).

I think the use of language post-disaster also betrays a certain mindset that wants to assign a narrative that anything “government” is fundamentally inept, and not just that launching things into space is really, really hard. It’s the seductive temptation to pigeonhole complex events into a pre-existing narrative, media or otherwise, and the failure of a rocket is no different.

But fundamentally, the Antares’ mishap provides us with a great opportunity not only to be reminded of the amount of work that goes into being a space-faring society, but also that some truly exciting things are happening in space. A rocket exploded off the coast of Virginia and it caused a company’s stock price to drop, since it was that company’s rocket. That’s actually pretty amazing. And over time, and as people truly internalize what’s going on, we’ll see the language of the U.S. space program diversify from NASA-only to NASA-and-commercial-industry. And that should be enough to make anyone’s head explode. Metaphorically.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth