Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 16, 2013

Juno is in Safe Mode again, but still okay

All Earth flyby data on the ground, including JunoCam images

I just got off the phone with Rick Nybakken, Juno Project Manager, with an update on Juno. I had originally called two days ago to get some information for a wrap-up story on the Earth flyby. I didn't know when I called that while Juno had been brought out of safe mode after entering it during the Earth flyby, the spacecraft went back into safe mode on Sunday. As of now it is still in safe mode. Nybakken told me they expect to be back to normal by the end of next week. In this phase of the mission, there's no need to hurry and every reason to take things slowly.

I have some notes from that conversation below, but first, I have to share: JunoCam's first image of Jupiter. Don't get too excited -- it's just a squished dot, with no moons visible -- but: land ho!

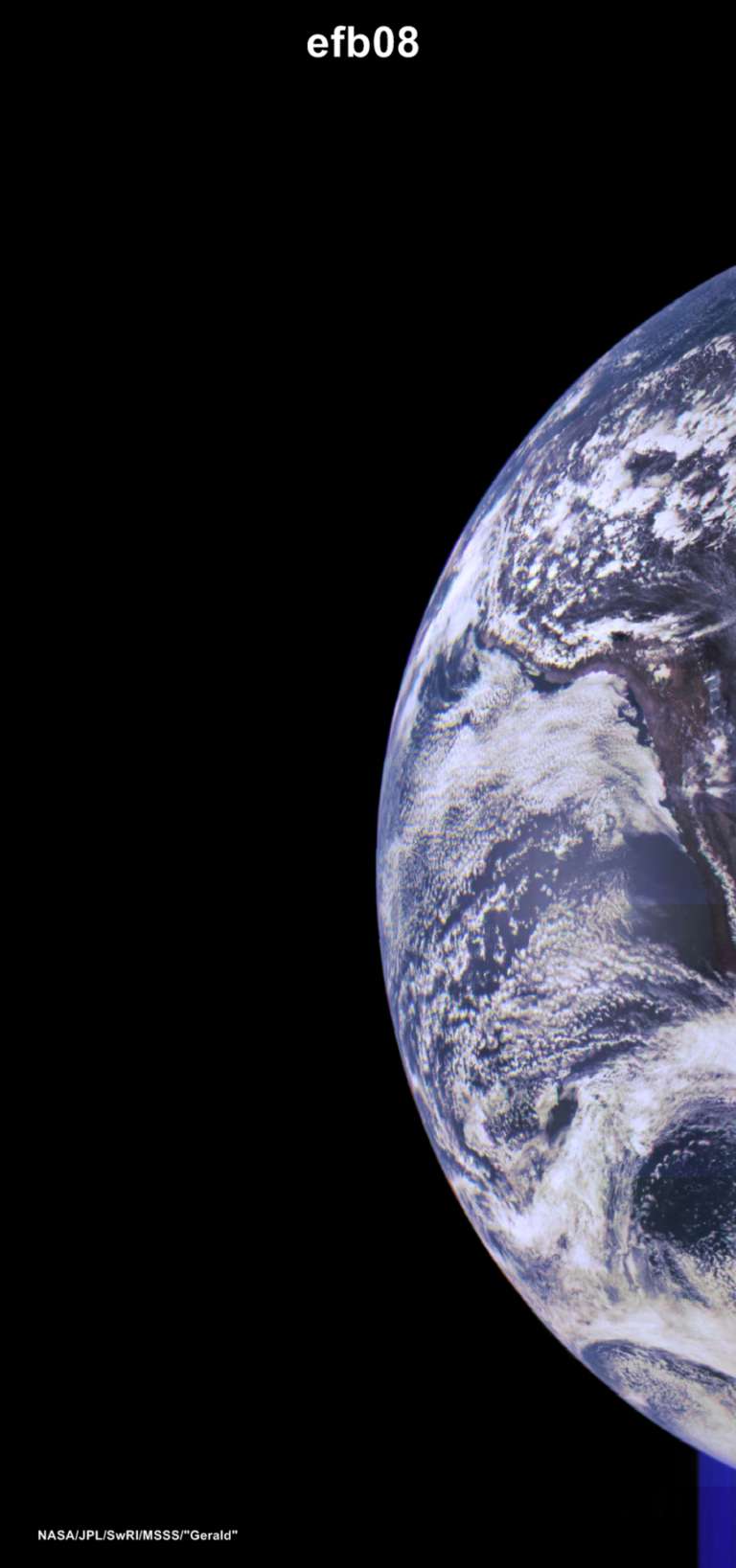

And here's just one cool image of Earth from JunoCam. There are lots more works in progress in this thread at unmannedspacefight.com; the original raw image data can be found here.

I exchanged email with the JunoCam team leader, Candy Hansen, about the performance of the camera during the flyby. Here's what she had to say:

I am really encouraged by the image processing work that the amateur image processing community has carried out. Since JunoCam is a multi-color push-frame imager it is not simple to reconstruct color pictures. But the amateur community stepped up and we now have some very beautiful images of earth and the Moon. Right after the data arrived, literally in the middle of the night in the US, one person on unmannedspaceflight.com in Poland put together the first color reconstruction. A few hours later another forum contributor had rotated the image so that north was up and he identified the features visible in the image. Another image processed by an amateur made it from Universe Today to NBC news, without any help or prompting from the Juno project.

This is precisely what we were hoping for when we added JunoCam to the Juno payload. We have a tiny ops team. We are not only inviting, but also relying on, the public to be our virtual team.

We will occasionally take images of star fields during cruise. Our next set of images will be right after Thanksgiving. Early next year we will attempt to image ISON.

That is awesome. Back to business: here's some notes from my conversation with Rick Nybakken:

- Apart from the safe mode thing, the gravity assist flyby was very successful; Juno's trajectory coming out of the flyby was "near perfect." "The navigators just did an excellent job."

- The safe mode entry occurred 10 minutes after closest approach, at 19:31 UTC.

- The safe mode entry occurred 12 minutes after the spacecraft entered eclipse.

- All command sequences executed nominally up to the moment that it entered safe mode.

- Juno acquired all high-priority data before entering safe mode.

- All of it has been downlinked and has been passed to instrument teams.

- All science instruments that were on during the flyby operated as expected up until the safe mode entry.

- There were only a few minor data gaps, only one remaining of which is sufficient to require retransmission, having to do with one of the JunoCam images.

- All engineering data from the flyby has been downlinked and examined by the ops team.

They haven't yet concluded their "cause investigation" for why Juno went into safe mode, but they have a leading hypothesis. "The likely cause appears to be an incorrect setting for a fault protection trigger for the spacecraft battery," Nybakken said. "Preliminary indications are that we set that trigger level a little too tight. There might be other factors involved, but it won't be clear until we complete the investigation." The spacecraft gathers power from solar panels, and the solar panels charge batteries. When the spacecraft went into Earth's shadow, the battery stopped charging, so its level was dropping. This was expected. But it looks like they didn't tell the spacecraft the right level of charge to expect the battery to drop to; so when the level dropped lower than expected, the spacecraft safed. Once in safe mode, it behaved as it was intended to.

Nybakken pointed out to me that this is the last time Juno will ever be in the shadow of a planet. There will be only two more times when the spacecraft will intentionally turn its solar panels away from the Sun. These are two 70-minute periods, one when Juno is performing the orbit insertion maneuver at Jupiter, and the second when it is performing its "period reduction maneuver" to accomplish the final adjustment of its orbit to an 11-day period. At all other times, the spacecraft's panels will be facing the Sun and the high-gain antenna toward Earth. They actually had to build a special low-gain antenna for the orbit insertion maneuver so that the spinning spacecraft can remain in contact with Earth while facing sideways. This toroidal low-gain antenna broadcasts all the way around the spacecraft so that even as it spins it can stay in communication. "It turns out it's not the easiest thing to design, either!" Nybakken said. "It literally scintillates a donut around the spacecraft."

I asked about data from other science instruments -- whether any of it is useful scientifically. He told me that the team liked to joke about using it to search for intelligent life on Earth. In particular, the Waves instrument was listening for ham radio operators on Earth who were participating in a project called "Hi Juno" -- the hams were broadcasting a coordinated Morse code message saying, literally, "hi". Nybakken told me that the Waves team is still processing their data; the team will have another tagup meeting tomorrow or Monday to discuss it. The safe mode entries have slowed them down in their analysis work.

Which brings me to the second safe mode entry. It happened on Sunday evening; Nybakken said they are still investigating the root cause, but again, they have a strong candidate hypothesis. "It happened when we reconfigured the onboard computer to transition from the Earth flyby to Cruise sequences. A stellar reference unit -- basically a star tracker -- remained in Earth flyby configuration. It had an unexpected current draw that tripped a safe mode. Again, the spacecraft operated as expected. There was no damage to the stellar reference unit or spacecraft components. Everything is safe and stable. The spacecraft acted as it was intended to, turned to Sun and called home."

In this phase of the mission there is no rush to exit safe mode; the spacecraft is not planned to collect any science data, nor does it need to do any propulsive maneuvers for a while. There is one planned trajectory correction maneuver, TCM-9, which is intended to clean up any residual error from the major Earth flyby maneuver. But they "can execute that without any mission impact all the way out into December, if need be." Nybakken said. He repeated that they expect to be out of safe mode again late next week.

The spacecraft will only perform very small propulsive maneuvers from now until its orbit insertion on July 4, 2016. I asked him if they plan to operate the instruments at all during orbit insertion, the way they did with Cassini, and he said they hadn't decided yet. "We will take a look at both feasibility and need to do that," he said. One possible "need" would be to use the non-scientifically-critical observations to confirm whether their predictions for Jupiter's space environment are correct, which could influence their mission planning. But, he repeated, they haven't decided yet.

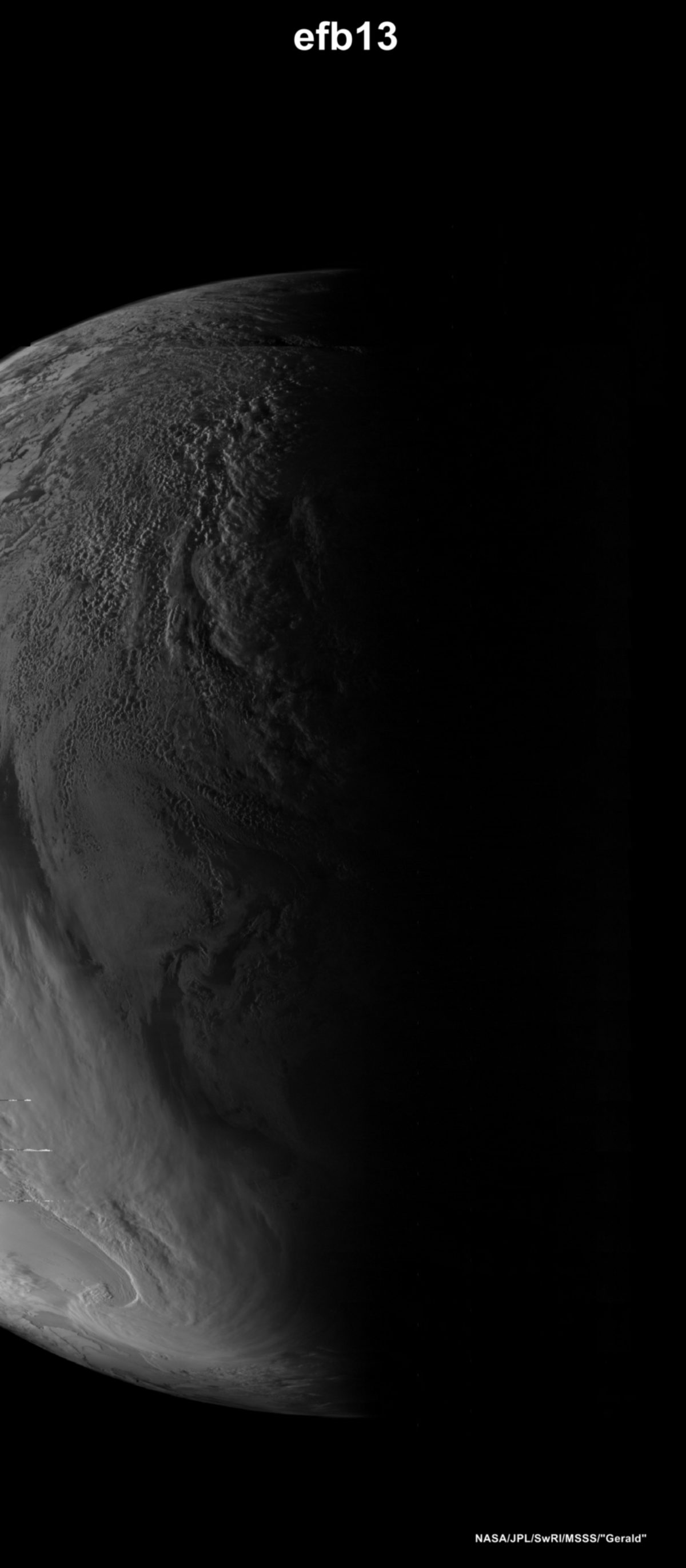

That was it. Assuming they exit safe mode as planned next week, and barring any future problems I shouldn't have any need to discuss Juno for a couple of years now. I will keep watching the JunoCam thread at unmannedspaceflight.com to see how the amateurs' work with the Earth flyby data is proceeding, and at some point I may post a followup with more of them. In the meantime, I'll leave you with another favorite from the flyby -- and I'm looking forward to those star field and ISON images that Candy talked about!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth