Emily Lakdawalla • Jun 14, 2007

Dione and Tethys: New members in the club of active bodies?

The European Space Agency issued a press release yesterday stating that Saturn's moons Tethys and Dione are "flinging great streams of particles in to space....The discovery suggests the possibility of some sort of geological activity, perhaps even volcanic, on these icy worlds."

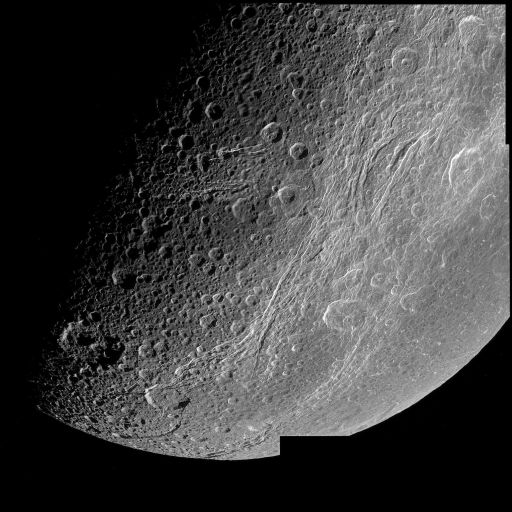

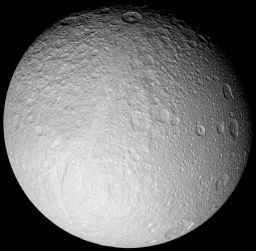

So far, the list of bodies in the solar system that have been caught in the act of some kind of geologic activity is very, very short. There are four: Earth, Jupiter's moon Io, Saturn's moon Enceladus, and Neptune's moon Triton. There are other bodies whose relatively crater-free surfaces suggest that activity has taken place recently (such as Venus, Jupiter's moon Europa, and Saturn's moon Titan), but Earth, Io, Enceladus, and Triton are the only ones who have displayed incontrovertible evidence that they're active right now. So if it's true that Cassini has observed Dione and Tethys being active, then the list of active bodies in the solar system has suddenly become 50 percent longer than it was before. They'd be very surprising additions, because these two worlds do not look the part; they're both heavily cratered -- Tethys especially -- indicating that their surfaces have changed very little for billions of years.

NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute

Highest-resolution global mosaic of Tethys

Tethys as seen by Cassini on approach to its September 24, 2005 flyby. Ithaca Chasma stretches from Telemachus crater in the north, down to the south pole. It wraps around a large impact basin that has been so battered by subsequent craters as to be nearly invisible. SourceOK, so there is suggestive evidence that Dione and Tethys might possibly be doing something interesting geologically. At the same time, their appearance -- both heavily cratered, especially Tethys -- tends to make me skeptical that there's much going on inside them. What's the next step? When the magnetometer team discovered that Enceladus was disturbing Saturn's magnetic field, they argued very strongly for closer flybys of Enceladus that might allow Cassini's other instruments to detect an atmosphere there. In the end, it took nearly all of Cassini's instruments acting in concert over three close flybys of Enceladus -- one of them passing right by the active south polar region -- to nail down the existence of the south polar geysers, and there's still plenty to learn there. So much, in fact, that after the primary mission (which includes one more close flyby) ends, Cassini's extended mission calls for seven more close Enceladus flybys.

How about Dione? There was one 500-kilometer flyby already, on October 11, 2005, and there'll be one more in the extended mission; I'm not sure if 500 kilometers is close enough, and I don't know if the geometry is correct, for Cassini to catch Dione in action. For Tethys, the only reasonably close flyby to date was on September 24, 2005, at 1,500 kilometers; the extended mission doesn't call for anything much closer than that.

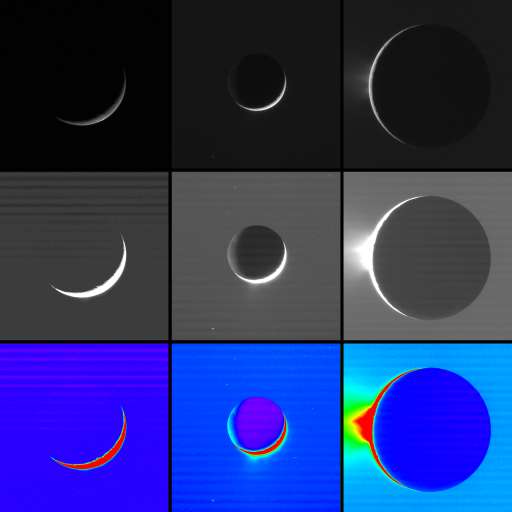

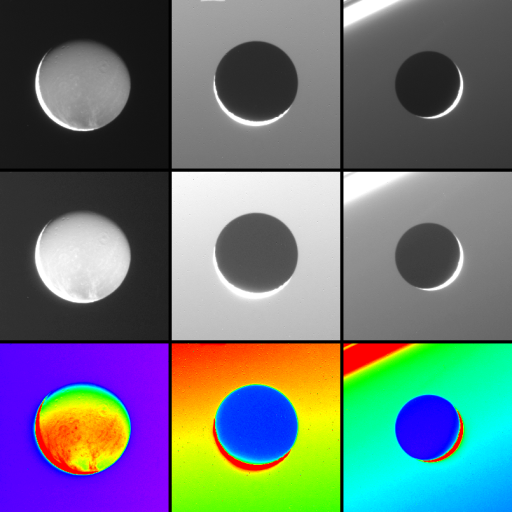

Although the Enceladus story was really pinned down with measurements that needed to be made up-close by the fields and particles instruments (magnetometers, particle detectors, and mass spectrometer), important evidence came in the form of images and temperature measurements made from a distance by the cameras and thermal infrared spectrometer. Pictures of Enceladus taken from "high phase angles" -- that is, where the Sun shone from nearly behind the Moon, illuminating the fine particles in the plume from behind -- really showed off the geysers. I dug in to the data that's been released to the Planetary Data System to find the high-phase views of Enceladus to date. These three observations were made on January 16, February 17, and November 27, 2005 from phase angles of 147 to 161 degrees, and the two on the right clearly show the geysers sprouting from the south pole. The first row of images are not stretched; the second has had the contrast adjusted to show off the plumes more; and the third row has had a color table applied to emphasize the plumes.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth