A.J.S. Rayl • Oct 31, 2010

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Remains Silent, Opportunity Pushes on to Endeavour

For the Mars Exploration Rovers, October was a lot like September, which was a lot like August: Spirit continued hibernating at Gusev Crater or so it appears since the rover didn’t phone home; and Opportunity picked up the pace to Endeavour Crater again, setting new driving records and marking more milestones along the way.

“It’s pretty much been more of the same at both places,” said Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, the principal investigator for rover science. “With Spirit, we’re just waiting. We’re in the any-day-now phase. And every time I check my email, I think: ‘Maybe this will be it,’” he said during a recent interview. “It hasn’t been yet. But I remain optimistic. With Opportunity, we’re chuggin’ along,” he continued. “The rover is getting really good mileage these days, doing 100-to-120-meter drives pretty routinely. We’re in a mode where we’re waiting on Spirit and trying to cover ground with Opportunity,” he summed up. “And these things take time.”

At Gusev Crater, Spirit sat silently through October, parked at Troy exactly where it was last February when it got too cold to continue trying to extricate itself from the sand patch just to the west of the old circular volcanic plateau known as Home Plate. In April 2009, the rover’s left three wheels broke through a crusty top layer of soil on the edge of what turned out to be a hidden, shallow, sand-filled crater, and churned into soft sand.

When another wheel stopped working seven months later, Spirit could not maneuver into a position to slant its solar panels toward the Sun in time for winter, as it had for the last three Martian winters. As a result, engineers knew that Spirit was in for its coldest winter ever, and expected the rover, as it lost energy, to trip a low-power fault and enter a hibernation mode. On March 22, Spirit sent its last communication. The assumption is that the rover began hibernating shortly after that, as it is programmed to do.

NASA engineers have been using the Deep Space Network (DSN) and the Mars Odyssey orbiter to listen for and reach out to Spirit, anticipating the moment when the solar-powered rover has re-charged its main batteries, and is awake again.

While some team members are getting anxious, some pessimistic about Spirit’s chances of emerging from hibernation, most of the MER veterans are simply waiting.

“Our early prediction of the most wildly optimistic time that we could hope to hear from Spirit was about mid-September, said Bill Nelson, the MER rover engineering team chief at the Jet Propulsion Laboratories (JPL) where the rovers’ mission control is located. “The more probable optimistic time was mid-October. So we’ve actually only been in the recovery period for not quite two weeks. That recovery period extends until April of next year, which is the time of the summer solstice. We still have quite a ways to go before energy really improves. We are just barely on the cusp of the predicted recovery period and our predictions have error bars.”

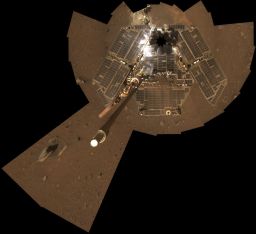

Hoping for an encore

Hoping for an encoreFrom Sols 1976-1978 (July 24-27, 2009) Spirit tipped her panoramic cameras down to acquire a self portrait. The solar arrays are shown here cleaner than they had been in years, the result of a lucky gust of wind. "The vertical projection used here produces the best view of the rover deck, though it distorts the ground and antennas somewhat," noted Pancam Instrument Lead Jim Bell, President of The Planetary Society. "The eight-pointed star shape near the front of the rover (top of the image) marks the location of the camera mast, which is out of view of the Pancam atop the mast." The team is hoping a storm that blew through October 24, might have cleared some dust from Spirit's solar arrays.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

The margins of error in the models, along with the lack of engineering data from the rover, leave the MER engineers guessing as to how Spirit may signal she’s awake. They assume the rover tripped the low power fault, in which case she should be phoning home any time now. But she might have gotten so cold that she tripped the mission clock fault and effectively lost track of time. If that’s the case, then the rover would be waiting and expecting her crew to initiate contact.

While the scene at Gusev is quiet, the rover engineers at JPL on Earth are trying to prepare for anything. “We’re waiting to hear from her and we’re optimistic that we will,” said Matt Keuneke, the integrated sequencing team chief at JPL. “But we are cautious, and reviewing everything, because we don’t know what fault mode(s) she will be in or what exactly we will be dealing with.”

Spring officially begins next month at Gusev Crater and the belief is that the conditions are warming and improving for Spirit there as they are for Opportunity at Meridiani Planum. But the Martian spring also gives life to the planet’s notorious winds and dust devils. With the capability of taking form in a moment’s notice, dust storms are always an unknown factor for the rovers. They can, after all, mean life or death.

Last week, a dust storm blew right over Spirit. Since all the rover’s systems are shut down, no one knows the impact that storm had on the robot or at the location

Way back in the beginning, the MERs' lifetimes were originally expected to be limited because of dust accumulating on the solar panels, and blocking the sunlight. If the dust reduced harvestable solar power too much, the rovers would have trouble keeping their electronics warm enough to survive the cold Martian nights, especially in the winter. But gusts of wind have cleaned off both rovers' solar panels from time to time, allowing them to live long and prosper.

Right now however, no one knows if the storm helped blow off some of the accumulated dust on the Spirit’s solar arrays, or if it deposited more dust onto them. If one were to go by the rovers’ history with dust storms, the odds that it cleared more dust than it deposited are good, and Spirit got one of her best dust-clearing events ever right in the area where she’s parked. “We’ll just have to wait and see,” said Arvidson.

At Meridiani Planum, Opportunity made some serious tracks this month toward Endeavour Crater, it’s next big attraction and long-term destination. In fact, the rover was consistently and consecutively zipping for 100+ meters in a single jaunt logging more than 935 meters or half a mile in October.

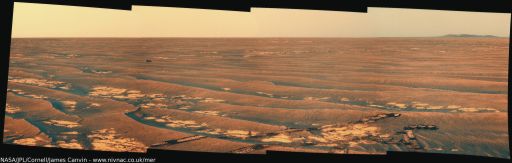

The road ahead from Oileán Ruaidh

The road ahead from Oileán RuaidhFrom her parked position at the meteorite Oilean Ruaidh, Opportunity took this drive direction mosiacked image of the 'road' ahead. Check out the tracks, ripples, bedrock, the meteorite named Ireland in the distance, and and the 'twin peaks' on the north rim of Endeavour. This month, the rover drove beyond this last expanse of bedrock and is now on flat sandy terrian heading for a small crater dubbed Santa Maria.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / processed by James Canvin

“We’re driving across what is really one of the last large expanses of bedrock that we’re going to see,” noted Squyres. “It sort of peters out after this.” That is, he reflected, both a bad thing and a good thing. “There’s a lot of science in the bedrock and we’re not going to see much more of it. But at the same time, the sand is easier driving as long as there aren’t big ripples. Once we motor past the last of the bedrock, it’s basically peddle to the metal,” said Squyres. Endeavour is now about 8 kilometers (4.97 miles) away by the rover’s charted course.

The end of bedrock or not, no one is looking back. As Opportunity paused this weekend to look out on the sandflat, as Arvidson calls it, the parking-lot-like stretch of terrain -- the direction is forward and the gear is in drive. The rover will “stop and look at things occasionally,” as Squyres put it.

The next science stop on the agenda is Santa Maria, a young crater and an intermediate destination, about 2 kilometers ahead. The plan right now calls for Opportunity to keep on truckin’ to the crater.

Other than its old injuries -- the broken shoulder joint on its arm, the troublesome, slightly toed-in, “hot” right front wheel, and an unresponsive miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) -- Opportunity appears to be mustering the determination that defines these rovers. Driving backwards, the rover has had to hang its instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm in a slightly unstowed position because of its broken shoulder joint. Although it was not designed to drive that way, the rover has followed sequenced drives and driven autonomously too with seemingly nary a care, ignoring its handicaps. “As long as we’re driving backward, it’s been smooth sailing,” said Keuneke.

Water flowing underground

Water flowing undergroundThis mosaic of images shows the soil in front of Spirit after a series of short backward drives during attempts to extricate itself from a sand trap in January and early February 2010. It is presented in false color to make some differences between materials easier to see. Bright-toned soil was freshly exposed by the rover's left-front wheel during the drives and can be seen with a "sand wave" shaping that resulted from the unseen wheel's action. Olive Pit and Olive Leaf are two of the analyzed targets. The investigations determined that, under a thin covering of windblown sand and dust, relatively insoluble minerals are concentrated near the surface and more-soluble ferric sulfates have higher concentrations below that layer. This pattern suggests water has moved downward through the soil, dissolving and carrying the ferric sulfates. The brightness and color of the freshly disturbed soil seen in the center area of the mosaic indicates the this formerly hidden material is sulfate-rich.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

As October falls into November, the MER team will continue to try and make contact with Spirit as they cheer Opportunity on to Santa Maria, and then Endeavour.

The MER scientists, meanwhile, are tending to other aspects of the mission beyond operations, not the least of which is writing papers.

A report in the Journal of Geophysical Research by Arvidson, Squyres, and 36 co-authors about Spirit's operations from late 2007 until just before the rover stopped communicating in March made the news this month.

“Snow on Mars!” television anchors billboarded, as they reduced to a soundbyte the evidence that water, perhaps as snow melt, trickled into the subsurface of Spirit’s location fairly recently and on a continuing basis.

Stratified soil layers with different compositions close to the surface led the rover science team to propose that thin films of water may have entered the ground from frost or snow, as reported here in the MER Update last April. The seepage could have happened during cyclical climate changes in periods when Mars tilted farther on its axis. The water may have moved down into the sand, carrying soluble minerals deeper than less soluble ones.

The relatively insoluble minerals near the surface include what is thought to be hematite, silica and gypsum. Ferric sulfates, which are more soluble, appear to have been dissolved and carried down by water. None of these minerals are exposed at the surface, which is covered by wind-blown sand and dust. " The lack of exposures at the surface indicates the preferential dissolution of ferric sulfates must be a relatively recent and ongoing process since wind has been systematically stripping soil and altering landscapes in the region Spirit has been examining," said Arvidson.

“We’re cranking out papers, and we’re still behind,” said Squyres, even as Opportunity prepared for its next drive. “When you have to prioritize your time, the highest priority always gets place on flight operations as opposed to writing papers. The data will be there and the opportunity to publish will always be there,” he reminded, offering up his trademark rationale. “But a sol on Mars that’s lost is a sol that’s gone forever.”

Spirit from Gusev Crater

It’s been 18 months now that Spirit has been parked in essentially the same spot, along the edge of the shallow, sand-filled Scamander Crater to the west side of the ancient volcanic formation known as Home Plate. With her last communication on Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010), MER team members are left to wonder and hope for the best, to believe that the rover did as programmed and that the brutal cold of the Martian winter didn’t take out any critical components.

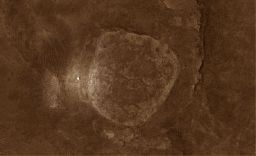

Spirit still shining at Troy

Spirit still shining at TroyIn this picture of Home Plate, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, you can easily see the stark white figure that is Spirit to the left (west) of the geologic formation in this image enhanced by UnmannedSpaceflight.com's Stuart Atkinson. "If you look carefully you can actually see bright trailing leading to Spirit," he notes, "This is the result of the (right front) broken wheel being dragged through the dirt, unearthing brighter material beneath." For more of Atkinson's enhanced images, poems, and thoughts. particularly of the targets being investigated by Opportunity, check out his Road to Endeavour: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by S. Atkinson

NASA engineers continued throughout the month to listen for Spirit throughout October using both the Deep Space Network (DSN) and the Mars Odyssey orbiter for the autonomous recovery ‘beep’ from the low-power fault they believe she tripped, as well as reaching out with a sweep-and-beep strategy to nudge the rover with a kind of wake-up call in the case Spirit also tripped a mission clock fault and lost track of time.

As the spring Sun is rising higher in the sky, Spirit should be recharging her two main power batteries. Once the batteries are sufficiently powered up, the rover is designed and programmed to wake up and initiate recovery by phoning home. If however the rover also tripped the mission clock fault, then the MER engineers will have to reach out and send a signal to Spirit, because the rover is programmed in that scenario to wait for instructions from Earth.

Now is about the time -- in the best of possible scenarios -- that Spirit’s energy levels could be adequate to wake up and emerge from hibernation. “But there’s a lot of uncertainty on that,” reminded Nelson. "And it doesn’t take much in this situation to have a significant impact. If the temperature is just a few degrees different, for example, that could have a dramatic effect, especially around the thresholds where heaters turn off or turn on,” Nelson explained. “The [battery survival] heaters can drain the charge out of the battery that you expected would have charge the rover back up. And it doesn’t take more than some really tiny percentage differences on how fast dust accumulates, for example, to make a big difference after 300 to 500 sols. Plus, we don’t really known how accurate our temperature measurements and predictions are because of the large error bars.”

“We’re in unfamiliar territory here,” summed up Squyres. “We’ll just see what we see.”

In recent weeks, the MER engineers have been reviewing everything in preparation for recovering Spirit. “We’re just double-checking everything and we continue to do planning for recovery, and that includes doing modeling for the various fault modes that we think we might be in,” said Nelson.

Spirit at Troy

Spirit at TroySpirit is like a golf-cart on the shoulder of Home Plate in this artist's rendition showing the rover's position where she became bogged down at Troy. The panorama was taken by the rover on its Sol 743 as she descended from Husband Hill toward Home Plate, the circular plateau in the center of the image; the rover is in the valley to its right.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Glen Nagle

During these reviews, they discovered some timing differences from what the original tests showed and what models are now showing. The engineers discovered the discrepancies during tests in JPL’s In Situ Instrument Laboratory (ISIL) with the rover on the ground, Nelson said.

“For example, we thought the rover -- if it were in mission clock fault -- would be in a pattern where it would wake up for 20 minutes or up-too-long time, then shut down for 40 and wake up again in another hour,” recounted Nelson. “Our documentation says 1 hour, and our test bed testing shows it’s really not quite that. We’re finding that it’s only about 51-52 minutes. It’s not a big difference. The basic concept is still the same. But it has caused us to look at certain little details,” he said.

“We’re currently using the sweep-and-beep strategy in case Spirit has tripped the mission clock fault,” Nelson continued. “We generally conduct a sweep, which is swinging the uplink through a relatively wide range in the expectation that at some point we pass through the capture band of the receiver and it will lock onto the signal and follow that frequency change, and then bring it back to our so-called best-lock frequency. Thereafter, we do the beep, which is first, command 1, then wait until that beep executes, then we repeat the process. The timing on that was fitted to 17 minutes, and we liked 17 minutes because it was a prime number and it was also relative prime to 60 minutes. It turns out, of course, that 17 x 3 is 51 minutes. That means that if you’re phasing was such that you just missed on one wake-up, you would just miss it again on the next wake-up. So we’re contemplating changing the timing a little bit, so that we have different phases on the presumed different wake-ups, so one or another of them should be caught.”

Basking in the glow of spring, we hope

Basking in the glow of spring, we hopeThis artistic image -- in which Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover -- illustrates Spirit's approximate position and location in the area now known as Troy within Gusev Crater. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers readers an idea of the rover's present scene.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

While there is always the chance the engineers are missing a signal from Spirit due to noise, it’s not probable, Nelson said. “We are using the Radio Science Receiver (RSR) -- and it’s effectively a very wide bandwidth radio signal recorder. If there were any signal from Spirit over that wide bandwidth -- any energy there at all -- the RSR should pick it up. And because we believe the frequencies would be different, the receiver is able to differentiate between the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO)signal and our putative signal. So far, we’ve seen nothing -- whether there’s been MRO interference or not,” he noted. [Spirit and MRO share a frequency, for the simple reason that no one expected Spirit to still be around when MRO dropped into Martian orbit in March 2006.]

With a little reminding and a little revving up, even the downhearted among Spirit team members are “bucking up,” said Nelson. “I’m pleased to see that, because this is probably going to be a long slog. Like I said, it’s still pretty early to really expect a recovery, so I’m not surprised we haven’t heard from Spirit yet.”

Past that, we are talking about Mars. “We have a lot of uncertainty in the modeling; therefore, a lot of uncertainty in the predicts,” Nelson added. “We’re still not done figuring out all the nuances of the recovery procedures, although we have made pretty good progress on that. But w ’ve never been through this before, and it’s not something that is easy to simulate on the ground.”

For one thing, Spirit is in a different configuration now on Mars that when the original tests were conducted on Earth, and, for another thing, the test beds simply don’t have the fidelity that the actual rover has. Still, the discrepancy probably should have been caught earlier, said Nelson.

When there is enough power to wake-up, Spirit will get up for between five and 10 minutes, long enough to power things up and check for a signal called solar groovy, which essentially means the rover has 1.1 amps of power coming off its solar array. The simulations have shown that if Spirit is in the mission clock fault, the wake-up times tend to cluster toward the end of the solar groovy time and not the beginning. “That is in part due to the nature of the algorithm that tends to walk later and later in time and that is causing us to think about getting a little more time and trying to sweep-and-beep later in the sol,” said Nelson. “We still think the low power fault is the likely fault Spirit is in -- and not the mission clock fault -- but we have to cover all bases.”

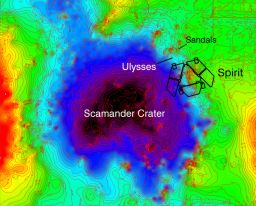

Topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy

Topographic map of Spirit's location at TroyThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed based upon Spirit's camera images of the location, taken before it got snared by the sand. The topographic model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander Crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State Univ

There is a feeling among some of the engineers though that the more time that goes by, the more likely Spirit has tripped the mission clock fault. “We are girding ourselves for whatever we may find,” said Keuneke.

The most unnerving thing is the team really has no idea how Spirit is doing, because all the rover’s systems are shut down and it is effectively soundly ‘sleeping.’ “We’re in very unfamiliar territory here,” Squyres reiterated. “We’ll take it as it comes.”

Just this last weekend, on October 24, 2010, a storm passed over the Spirit site, moving rapidly to the east, according to a report filed, from Mars Color Imager (MARCI) data, by Bruce Cantor, a staff scientist at Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego. The storm was expected to blow out of Gusev Crater within 24 hours and from the looks of things it did.

“Mars giveth and Mars taketh away, but we don’t know if the dust cloud is relatively high altitude or on the ground,” said Nelson. “So we don’t know whether it cleared dust from Spirit’s solar arrays or dumped more dust onto them, and of course we have no telemetry from the ground to give us the answer.”

Anticipation is building. “I’d been having the feeling that once the dust storm cleared away, Spirit might be phoning home soon and this is right around the time we expected to begin hearing from her,” said Keuneke. “I am very optimistic and we need to be prepared and careful not to be blindly optimistic.”

Mars at opposition in 2005

Mars at opposition in 2005The Hubble Space Telescope snapped this photo of Mars on October 28, 2005, a day before its 2005 opposition. A large dust storm occupies the near-center of the globe (it is the brightest feature in the image).Credit: NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), J. Bell (Cornell University) and M. Wolff (Space Science Institute)

Since Spirit’s energy should improve dramatically over the course of the next several months, the chances of hearing from Spirit should improve as time goes on. “And of course we’re taking all the steps we can to get her to talk to us,” said Nelson. “We want to recover her too.”

Once the MER team does recover Spirit, there’s plenty for the little rover to do.

“I think the most important Spirit can do is as a lander, specifically the radio tracking experiment to determine more about Mars’ inner core,” said Arvidson.

For that study, Spirit would record the wobble in the planet's axis of rotation, something that can’t be done with a mobile rover. Long-term change in the spin direction of Mars’ axis would inform scientists about the diameter and density of the planet's core, according to William Folkner of JPL, who has been patiently waiting the entire mission to do this research. "Short-period changes, for example, could tell us whether the core is liquid or solid," he said.

It’s pretty classic stuff as planetary science goes and it would be a glorious final experiment for Spirit. But a good number of engineers are also bent on seeing Spirit extricate herself from the sand patch at Troy, and move on, if only for a few tens of meters.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

After a brief stop to rest and check out an iron-nickel meteorite the team named Oileán Ruaidh, Opportunity resumed her trek to Endeavour Crater, the mission's long-term destination, and literally drove into October.

On the first sol of the month, the rover’s Sol 2377, Opportunity drove more than 100 meters (328 feet), deftly making a "bank shot" maneuver to avoid some troubling terrain. Two sols later, on Sol 2379 (October 3, 2010), the rover tested its autonomous navigation capabilities driving backward, using her rear hazardous avoidance cameras (Hazcams). Not surprisingly, she passed the test, completing just about 92 meters (302 feet) for the day. This new autonomous driving technique will enable the rover to make longer, backward drives on her own each sol.

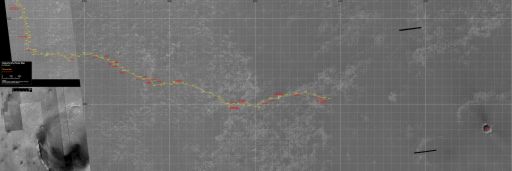

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis map compiled from HiRISE and Context Camera images taken on orbit from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and labeled by Eduardo Tesheiner shows Opportunity's route through its Sol 2404 (Oct. 28, 2010).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona, Malin Space Science Systems, E. Tesheiner

Opportunity headed out to the northeast to rejoin the original path to Endeavour crater on Sol 2381 (October 5, 2010), driving for about 86 meters (282 feet). She followed tht drive with a 93-meter (305-foot) drive the next sol.

Putting more than 370 meters (1214 feet) on her odometer during the first week of October, Opportunity seemed amped. In a way, she was. With spring warming up the plains, she was producing more than 600 watt-hours of power under typically hazy skies.

Then, on Sol 2380 (October 4, 2010), “a kind of perfect storm” began to coalesce, said Nelson, as Opportunity inadvertently began overloading her flash memory.

Looking east

Looking eastOpportunity took the images for this mosaic with its navigation camera. The picture shows a 90-degree view centered toward the east, just after the rover completed a 93.3-meter (306-foot) drive east-northeastward on its Sol 2382(Oct. 6, 2010). The terrain includes light-toned bedrock and darker ripples of wind-blown sand. On the following sol, Opportunity drove an additional 94.3 meters (309 feet) toward its long-term destination: the rim of Endeavour Crater. Portions of the rim, still more than 8 kilometers (5 miles) away, are visible in the horizon of this scene. This view is presented as a cylindrical projection.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

“We had way too many data products and we were getting very tight in our directory space,” Nelson recalled. “There are two areas of flash that we use for data products. One is the directory. It is a fixed size. We can only have a certain number of files regardless of their size. We also have a larger area that holds the actual data of that file, where, regardless of the number or if you’ve got big files, you can fill up that area. We had the worst of both possible worlds. Enough of them were big files that we didn’t have a comfortable amount of free flash for the actual storage of content,” Nelson explained.

High-quality range data with the Pancam stereo imaging has enabled rover drives of 100+ meters (328 feet). But in order to achieve drives beyond that, Opportunity has been driving some on her own following each sequenced drive as commanded from the rover planners on Earth, backwards autonav driving as it’s called. That requires that the rover take a lot of images. It then processes those images into various maps and checks for “goodness,” as Nelson put it, or usability, to see if it can find a good path.

“All of those data products are stored, because it is potential troubleshooting information if for some reason the autonav should have some sort of problem,” Nelson pointed out. “On the 2380 drive, Opportunity filled up flash with a lot more of those data products than we expected. We anticipated collecting 100 megabits of data and ended up collected 230 megabits of data.”

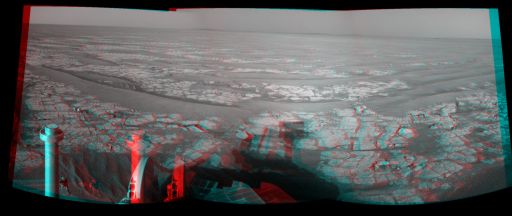

Looking east in 3-D

Looking east in 3-DPut on your red-blue glasses and check out this stereo view of Opportunity view to the east following her Sol 2382 drive during the first week of October. This image combines right-eye and left-eye views presented as cylindrical-perspective projections and appears three-dimensional when viewed through red-blue glasses (with the red lens on the left).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The engineers currently believe the issue lies not with the algorithm per se, but in their modeling of what the algorithm is doing. “The model didn’t figure out correctly the amount of data it was going to take. We have someone looking into that, but that investigation has not been completed,” said Nelson.

The hits just kept on coming during the second week of October. On Sol 2383 (October 7, 2010), the mission had we had a problem with the downlink from the Mars Odyssey orbiter, the main communication link for the rovers. “We expected 90 megabits of data to be sent down, but only received 34 megabits of data,” said Nelson. “That was primarily due to a DSN station problem that Odyssey had in sending its data back to Earth.”

What was missing was, of course, the critical stuff. “The Data Products Summary that tells us what’s been transmitted, what hasn’t -- what the data management team uses to clean up the disc space on the rovers -- wasn’t transmitted,” said Keuneke. “Without that file, they we couldn’t prepare the next data management bundle, and the data management team couldn’t complete their daily process and delete old products, so they continued to build up on the rover.”

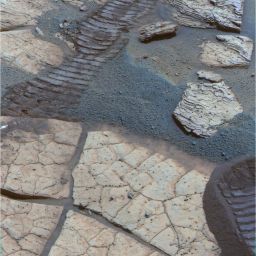

Puntarenas

PuntarenasOpportunity took this image of Puntarenas at an area of the so-called contact boundary on its Sol 2397 (Oct. 21, 2010) in preparation for an up-close, contact examination of the area with the instruments on the rover's robotic arm. This area ingtrigued the scientists because the outcrops seems to change character here.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell University

Thus the backlog -- and a drive stand-down for Opportunity -- began. “They decided since they couldn’t do data management on Sol 2385 (October 9, 2010), they would wait until Sol 2388 (October 12, 2010) to send up the latest bundle,” Nelson said, continuing the story. But, just when that fix-it bundle was to be sent, the Deep Space Network station set to send it “went red” at the last minute, said Keuneke. That means, it went off-line.

With no back-up available, the DSN antenna outage prevented the team from uplinking the data management bundles that would have “cleaned out the backlog, re-prioritized, retransmitted, and deleted certain data products,” Nelson said.

“The unfortunate coincidence of those outages put us in a full-stomach sort of situation,” added Keuneke. “It was like the rover had over-eaten and didn’t want to move.”

On Sol 2390 (October 14, 2010), the MER team succeeded in getting a large data management bundle to the rover and two sols after that, a second data management bundle followed, Nelson said. That put the rover back in the pink and on track, ready to roll.

At the same time, a dust storm was spotted heading toward Opportunity by the Malin Space Science team operating cameras onboard MRO. The storm dissipated by the October 16th however. “It never did reach the rover,” said Nelson.

Opportunity kept working, snapping a pre-drive Pancam picture of Ataqui, and an area of darker outcrop the team dubbed Puenta del Este (East Point). Later, she sequenced her APXS in order to collect an atmospheric argon measurement, and do some light remote sensing.

Finally, by Sol 2392 (October 16, 2010), after more than 10 sols of not driving, the ground crew had freed-up onboard data space on Oppotunity to sequence a drive. Wasting no time, the rover took off, driving more than 100 meters (328 feet) to pass the 24-kilometer milestone. On Sol 2395 (October 19, 2010), the rover again logged more than 100 meters (328 miles) on her rocker bogie, this time chalking up her 15th mile. “There’s only 140 meters difference between the 24-kilometer and 15th mile milestones,” Nelson noted.

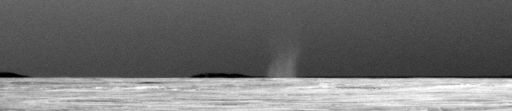

Opportunity's first dust devil

Opportunity's first dust devilThis is the first dust devil that Opportunity observed in the rover's nearly seven Earth years on Mars. The whirlwind appeared in a routine drive-direction image that the rover took with its panoramic camera right after a drive on its Sol 2301 (July 15, 2010). Contrast has been stretched, and the image has been carefully calibrated to make the dust devil easier to see against the Martian sky. Opportunity's twin, Spirit, has observed dozens of dust devils at its location in Gusev Crater halfway around Mars from Opportunity's location in the Meridian Planum region. Opportunity conducted systematic searches for dust devils in past years without seeing any. A rougher and dustier surface at Gusev makes dust devils form more readily there than at Meridiani, but with this sighting the team is having Opportunity keep an eye out once again.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University / Texas A&M

Between drives, Opportunity spent time monitoring the dust in the atmosphere, conducting Navcam dust-devil watches, taking pictures of its tracks and sky thumbnails with the panoramic camera (Pancam). And, even though the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) is still under investigation, the elevation mirror, which is obscured with dust, continues to be opened to the environment at regular intervals in the chance of catching a wind-induced cleaning event.

Opportunity completed a short 3-meter (10-foot) bump on Sol 2397 (October 21, 2010) before the October 23-24, 2010 weekend. The objective was to position the robotic arm instruments within the reach of an interesting geologic area. “We got to this outcrop contact and bumped back, took a picture and moved forward, then did what we call an IDD salute, which was to move the IDD up and out of way of Hazcams and take a high-resolution picture of the area to use for identification of targets and accurately place the APXS,” said Nelson.

The rover also took a Pancam picture of Puntarenas, a place on the expanse of bedrock where the outcrop seems to change its character. Then, on Sol 2399 (October 23, 2010), the rover moved her arm, took a series of pictures with her microscopic imager (MI) for a mosaic image, and then placed the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on the surface target Puerto Jimenez (Port Jimmy). This target on the lighter color side on this contact boundary area is within the more general area of Puntarenas, and the rover stayed focused for long integrations on its Sols 2399 and 2400 (October 23-24, 2010) to try and determine its composition.

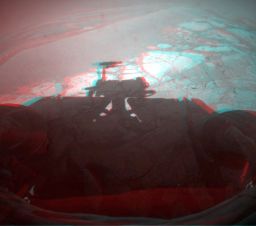

Opportunity self portrait in 3-D

Opportunity self portrait in 3-DOpportunity took this self-portrait in August 2010. Stuart Atkinson turned it into a 3-D experience.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / processed by S. Atkinson

“Jimenez was the interesting one, because there were some just spectacular polygonal fracturing, the mud-cracky looking stuff,” said Squyres. “The mud cracks are on the southeast side of Puntarenas facing Endeavour, and, polygonal in shape, they sort of look like flagstones,” elaborated Arvidson.

As for the so-called contact boundary, is it really a geologic contact, where two geologic units merge or overlap on each other?

“Here’s what we know,” offered Arvidson. “We know there are linear features that are kind of curvy and extend from northeast to southwest and they have dark sides and bright sides -- is it a geologic contact? We’re not sure. Is it a marine on-lap relationship, where the rocks are getting younger on one side? We’re not sure. It may be a fracture where one side is uplifted a bit,” he added.

“We spent some time over last weekend doing APXS and MI, and the material looks like normal bedrock,” Arvidson continued. “And the topographically higher area, where some layers are exposed, is toward the northwest, “exactly backwards,” he admitted, of what one would expect for rocks getting younger toward the Endeavour side, the theory proposed by JPL’s Tim Parker.

The debate is on for now. But one way or another Opportunity should be uncovering the clues soon. On completing the brief in-situ science campaign at the contact area, the rover drove away with a 122-meter (400-foot) drive on Sol 2401 (October 25, 2010). It looked back to take a mid-drive Pancam picture, and to take a picture of a spot called Golfito. The next sol, the rover logged another 93+ meters (305 feet).

Opportunity took a sol to rest then pressed on, driving the next three sols in a row, logging 128.72 meters (422.30 feet) on Sol 2403 (October 28, 2010), 44.11 meters (141.71 feet) on Sol 2404 (October 29, 2010), and 89.24 meters (292.78 feet) on Sol 2405 (October 30, 2010), coming to a rest on All Hallow’s Eve.

Changing terrain

Changing terrainThis series of terrain images taken by Opportunity on Sols 2329, 2337, 2374, and 2404, and compiled into this comparison image by Stuart Atkinson, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, shows how the landscape has changed for this rover during the last several months. The ripples have given way to a stretch of some of the flatest ground seen by either rover on the entire mission. By all accounts, it should make the rest of the rover's trek to Endeavour Crater a veritable breeze.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / compiled by S. Atkinson

Driving past the last expanse of bedrock marks the end of another chapter for the MER mission, but the team is ready, anxious for Opportunity to move on. “The sense of the team is: ‘Let’s get on with it,’” Arvidson said. “Let’s get on the sand sheet and move on down to Santa Maria.” That’s just what Opportunity is doing.

“We knew all along that the terrain was going to get easier and easier the closer we got to Endeavour and that is turning out to be the case,” said Squyres. “We’ve been covering ground very well.” This month alone, the rover logged 936+ meters, more than half a mile.

As October falls to November, Opportunity is looking out over a vast plain of sand. The rim of Endeavour and Cape York is just 8 kilometers (4.97 miles) away, and now more than ever, it’s all about driving for Opportunity. In coming weeks, the rover will be heading for another landmark about two kilometers down the road, a fresh, young crater dubbed Santa Maria, reminiscent of, though smaller than Endurance Crater.

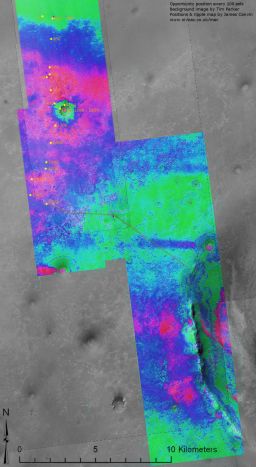

Opportunity position and ripple map

Opportunity position and ripple mapThis image shows Opportunity's position every 100 sols and was created from a background image by JPL's Tim Parker, with the positions and ripple map created by James Canvin. Santa Maria Crater is the little black dot to the right of the 2300 sol position.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Tim Parker / James Canvin

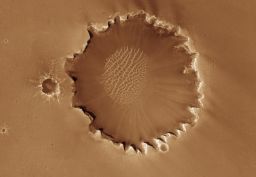

About 80 meters in diameter, Santa Maria boasts visible rays of ejecta in orbital photographs. “It’s undoubtedly excavated some fresh rock from the subsurface, maybe 10 meters down,” mused Arvidson. “It’s going to be pretty spectacular I think,” added Squyres. “And at the rate we’re covering ground, we’ll be there before you know it.”

In the meantime, the MER scientists secured a special super resolution image with the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), a visible-infrared hyperspectral mapper onboard MRO. CRISM has its optics on a gimbal or pivoted support that allows the rotation of an object about a single axis.

“As MRO flies over a site, you can actually point the gimbal so it stays fixed over a given spot as they rotate the whole spacecraft,” Arvidson explained. “We’re adjusting how we point the gimbal now, so we over-sample a long track of where Opportunity has been and is going. Rather than [resolution at] 18 meters per pixel, we’re down to six, which is comparable to the Context Camera (CTX) on MRO.”

The image CRISM took last Monday, October 25, 2010, was centered over Santa Maria. “We want to resolve a little more detail on the ejecta, and we want to use the CRISM data tactically to help Opportunity get directed to the juiciest spots,” said Arvidson.

The operations team will be keeping a close tab on data management, even though Opportunity’s stand-down this month was largely caused by forces outside of the MER mission’s control. “One of the factors that allowed that to be a problem, however, was keeping too much data onboard,” Keuneke said, “so we’re going to be a little more vigilant in the near term to make sure that we don’t acquire too much data all at once and have to stop again.

It remains to be seen when Opportunity will arrive at Santa Maria and how long it will stay. The crater likely will determine that. In any case, the rover’s prime directive has not changed. “When we see interesting, things, we’ll stop, but my hope is that we’ll be able to continue to cover ground as we head to Endeavour,” said Squyres.

Santa Maria versus Victoria Crater

Santa Maria versus Victoria CraterThis image shows a HiRISE image of Santa Maria Crater, on the left, superimposed on a HiRISE image of Victoria Crater, the larger crater on the right. In reality, these two craters are not located next to each other. This image was put together by rover aficionado Stuart Atkinson to show the difference in size between the two craters, for comparison purposes only.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / compiled by S. Atkinson

Given all that Opportunity has done and seen and how far it’s roved, Endeavour seems just a hop. Skip and jump around the corner. You can feel the energy emanating from the team members and excitement is building among rover followers for that day the rover sails into port at Cape York.

“I want to get to Endeavour’s rim and find those clay minerals,” enthused a determined Arvidson. As noted in previous MER Updates, the race between MER and the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) to be the first to find phyllosilicates, the minerals that hold water molecules in their make-up and are obvious evidence of past water, is on, even though Curiosity has yet to launch. “The only thing that’s going to stop us is science,” Arvidson said.

“I am always reluctant to make predictions, so you won’t be able to get me to make one,” Squyres said, resolute as always. “One of Opportunity’s wheels could die tomorrow and there’s no telling. But let’s just say, qualitatively, I share the optimism. Right now things are going well. We’re covering good ground and the rover is healthy. We take each day as a gift and keep going.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth