Casey Dreier • Sep 19, 2016

Promise, Transition, and Transformation

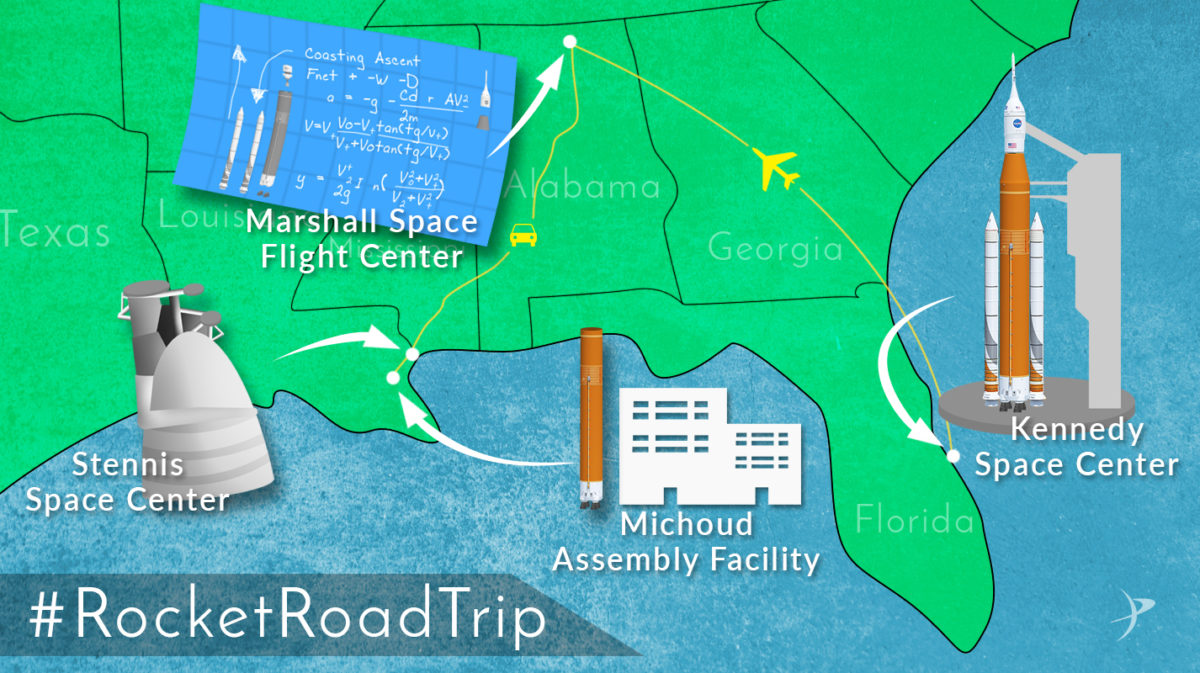

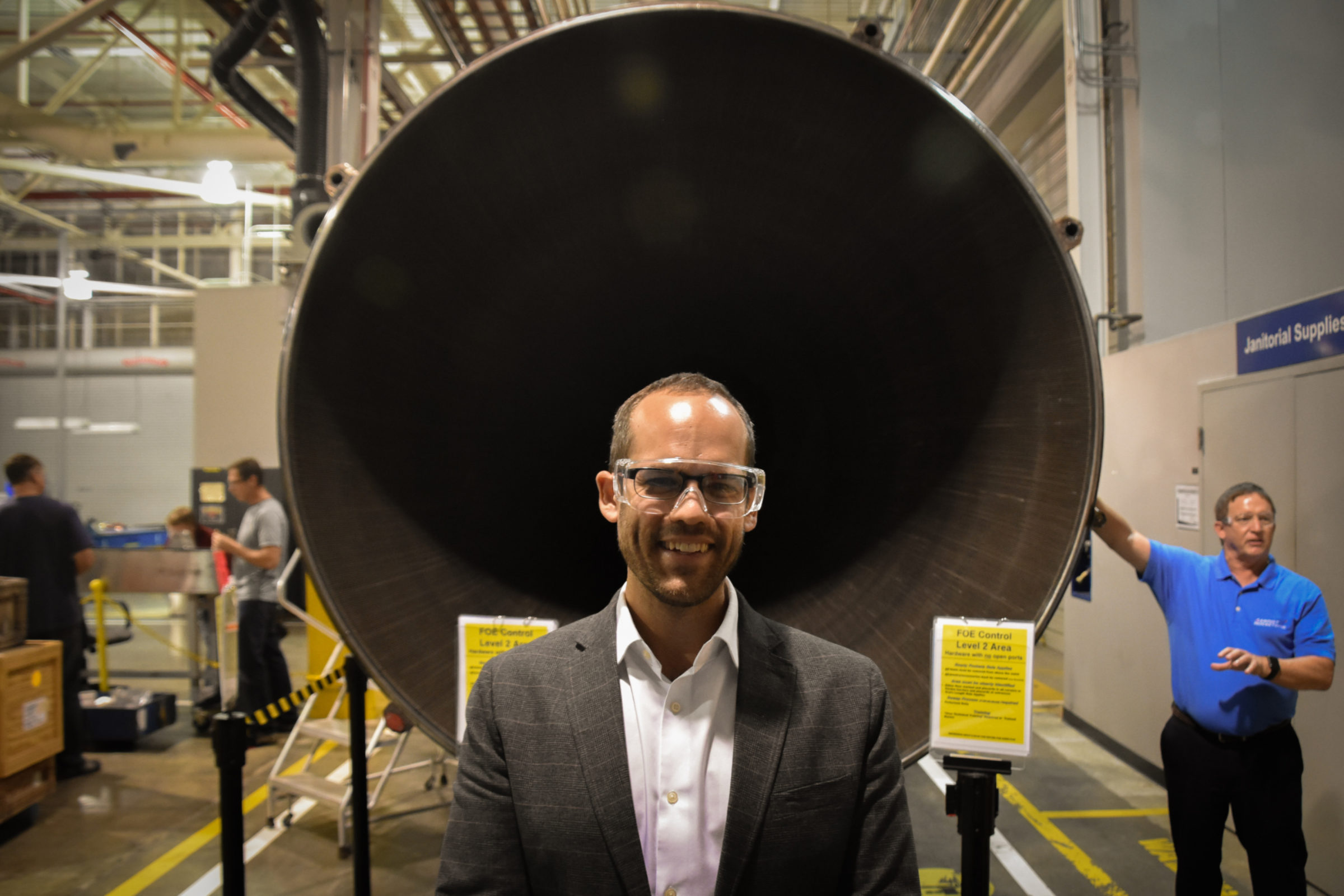

I recently returned from a 10-day tour of four NASA sites scattered around the southeast United States. I toured test stands, rocket engines, assembly floors, contractor offices, and high bays. Lots and lots of high bays. I heard the clamour of construction workers, the banging of metal, the grinding sounds of motors moving both machines and people. I saw monstrous pieces of metal towering above me that will fly into space in just a few years. What I saw was awesome in the literal sense of that word.

The Planetary Society—led by my colleague Jason Davis—is on a quest to better understand the impact of NASA’s big new rocket program, the Space Launch System (SLS), on major human spaceflight centers and their surrounding communities. Billions of dollars have been spent every year on this rocket since 2012, but NASA has yet to fly it. What’s been happening in the meantime? Jason’s ongoing reporting series, Horizon Goal, aims to find out.

The SLS program was born in political tumult early on in President Obama’s administration and has remained divisive within the space community ever since. There were reasons to be weary of the SLS. Its spiritual predecessors, the Ares I and V rockets, had fallen behind in their schedule and ballooned in cost. The program was essentially created by Congress via the 2010 NASA Authorization Act. The SLS uses “old-school” contracting methods in a time where new entrants like SpaceX were defining a new way forward for creating access to space.

But something interesting has happened since the SLS program began five years ago: the SLS has failed to fail. It is the first human-rated rocket system to pass a Critical Design Review since the Space Shuttle. Its budget, while very large, is not consuming NASA from within. Congress has provided new money and consistent political support. And while it certainly puts the squeeze on other programs (notably Commercial Crew), it has yet to crowd them out altogether. Somehow, within an unprecedented handicap of developing a new rocket within a relatively flat budget, the SLS is progressing steadily toward its goal of a 2018 launch.

But, as they say, past returns are no indication of future performance. And a lot yet needs to happen before the program is considered a success. Integration—bringing all of the disparate pieces of ground systems, the rocket, and Orion—tends to be the riskiest period of a program’s development, and we’re heading into that over the next few years. A Presidential transition is around the corner which could destabilize NASA’s direction and existing programs. Projections of ongoing costs and launch frequencies plague the program. Success is far from certain.

Despite this uncertainty, what we can say is that something rare is happening at NASA’s human spaceflight centers. The last time NASA underwent such a dramatic change was four decades ago during the transition from Apollo to Shuttle. Decisions and infrastructure investments made then echoed for nearly two generations. We are likely to see something similar with the SLS and Orion.

If the SLS was cancelled tomorrow, the underlying politics and motivations that drove Congress to create the program would remain: a distributed workforce and infrastructure designed for the needs of Apollo and adapted for the Shuttle. It’s not an abstraction. Tens of thousands of actual people and their families (who vote!) depend on NASA’s human spaceflight programs. You can’t just wipe the slate clean of this easily without political pushback.

These NASA employees and contractors appear to have new sense of energy and direction. Hardware is being made right now that is intended to fly into space in just a few years. The lead-up to this first launch has required a rejuvenation and reinvestment in NASA centers throughout the country. New tools to build the rocket. New logistics to piece it together. New methods of construction to make sure it works. Much of our last few years have seen the pieces being put into place to enable the outcome of a rocket sitting on the pad at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Understanding what these pieces are and why they exist is a fascinating story. Over the next few months, my colleagues and I will publish our stories, analysis, thoughts, pictures, and videos from our visits at these human spaceflight centers. There is a lot to process. It’s an exciting time. And like all transitions, the future is uncertain and a little unsettling. Strange enough as it is, NASA’s next big leap into the unknown isn’t so much about sending humans into space, but committing to a new rocket and and infrastructure that will take them there.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth