Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 11, 2015

How the duck got its neck: Rapid temperature changes from self-shadowing may explain 67P's unusual activity and shape

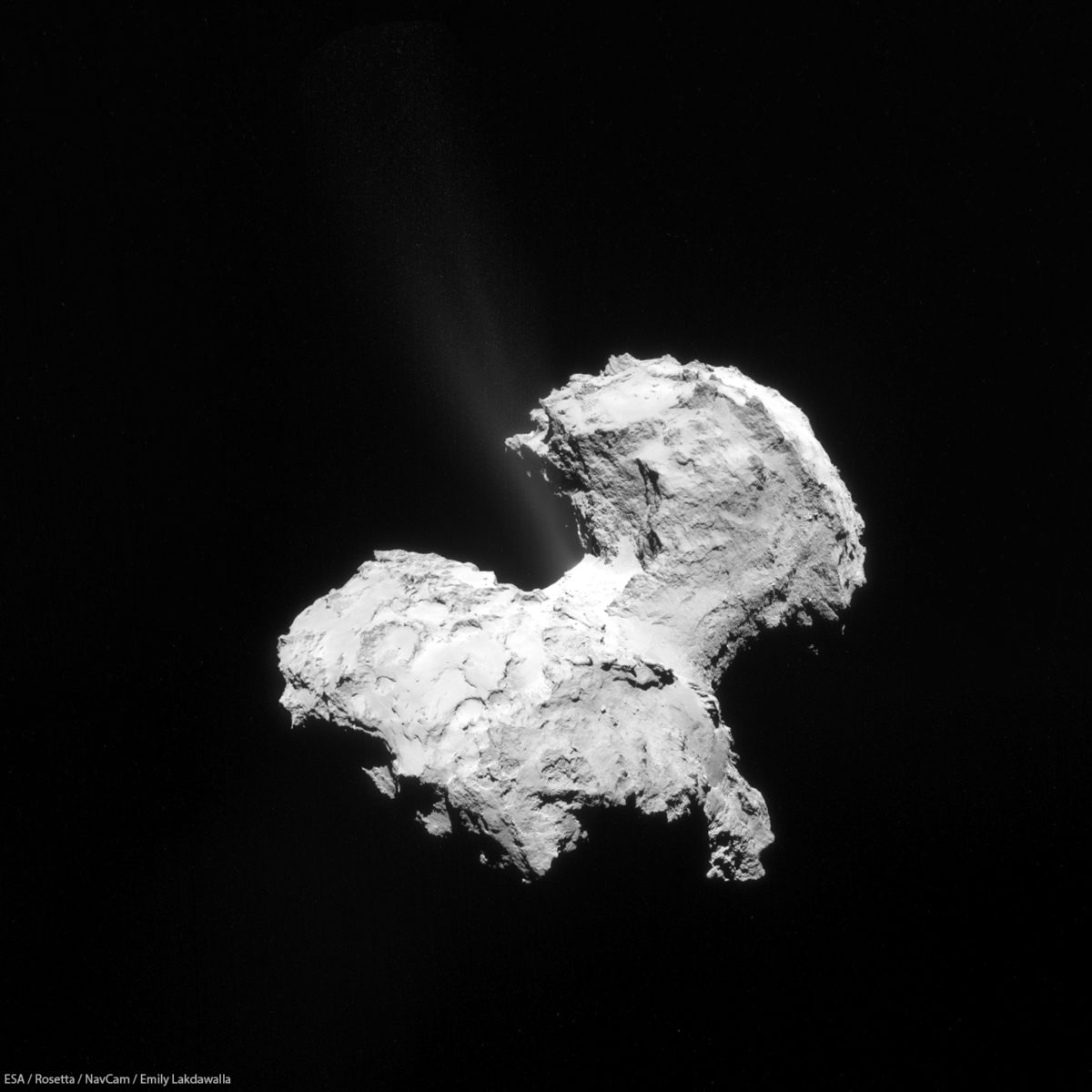

When Rosetta approached comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko last summer, both its shape and its activity were surprising. It looked like two comets welded together at a skinny neck. But just as surprising, to comet researchers, was the fact that the cometary activity appeared to originate within the neck.

Here's the reason that's such a surprise. The animation below was produced for Philae landing site selection, and it shows how much of the comet's surface was in sunlight at the time. Red areas are continuously illuminated, so are hottest. Cometary activity has to do with volatile materials (especially ices like water and carbon monoxide) being heated and sublimating. And yet the hottest regions on the comet -- its twin poles, one broad area on each lobe -- aren't making jets like the neck areas are. What gives?

A new paper published in the Astrophysical Journal by Victor Alí-Lagoa, Marco Delbo', and Guy Libourel presents a possible explanation. The three scientists do work in thermophysical modeling -- they use physics to examine how changes in temperature propagate through solar system materials, and investigate what happens to those materials as their temperature changes.

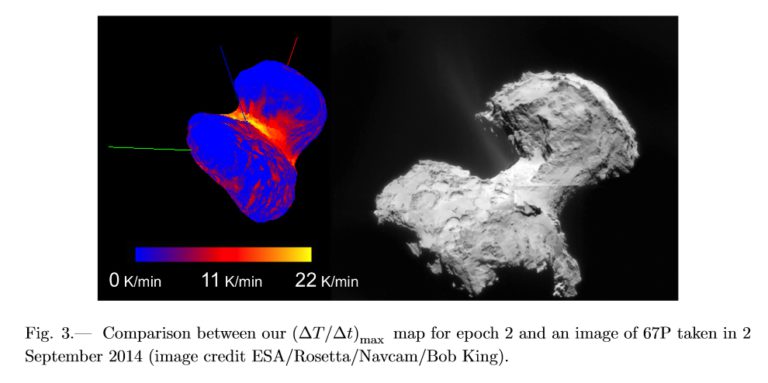

They asked whether the comet's unusual shape might have any effects on the temperatures experienced from place to place on its surface. They took a model of the rotating comet and looked at how its surface temperatures change as parts of its surface cast shadows on other parts, or reflect sunlight into shadowed regions, for four different dates. In their model, they found that while the neck area of the comet doesn't experience the most extreme temperatures, it does experience the most extreme temperature changes, where baking-hot sunlit surfaces are suddenly sunk into very deep shadows, and just as suddenly lit up again. On the two lobes of the comet, temperature change happens at only a few kelvins per minute; in the neck region, it can spike or plunge by more than 30 kelvins per minute. Here's one of their model results -- look at how that neck lights up! The places on the comet where temperature changes the fastest correlate well with the positions of observed jets.

Why does the rate of temperature change matter? In previous work, Delbo' and Libourel and other workers have explored how thermal changes can cause cracking. More rapid temperature changes make for higher stresses and more rapid cracking. Cracks in a comet can expose volatile material that was previously protected from the vacuum of space. The exposure of the material might not happen instantly, but a pervasively cracked surface will erode more rapidly, so cracks accumulated when the comet is close to perihelion could break open later. The authors explain: "In this case, ice would progressively be exposed on the concave parts and would subsequently be available for sublimation when the temperatures increase sufficiently as the comet approaches perihelion once again."

If true, this thermal-shock-cracking scenario might also explain the comet's two-lobed shape. A small initial concavity on the surface -- maybe an impact crater -- could, over time, through positive feedback, grow into a comet-bisecting neck. The authors go on to speculate that "faster thermal cracking in concavities might also explain why water ice was detected on asteroids (24) Themis and (67) Cybele (Campins et al. 2010; Licandro et al. 2011) at heliocentric distances at which water ice is not expected to be stable," and that the process might be quite common on small bodies in the solar system.

I'll carry the speculation a little bit farther: if a positive feedback mechanism has made a two-lobed world out of a single-lobed one, surely it will continue until it breaks the comet right in half. If the mechanism is common in ice-rich small bodies, as the authors suggest, I wonder if this is a pretty rapid way to disintegrate them: strike your comet or ice-rich asteroid with a biggish object to create a concavity, then watch the concavity grow until it cuts the thing in two, each of the resulting pieces being much smaller than the original. It's a wonder we have any little icy worlds left to visit!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth