Paul Schenk • Sep 08, 2017

Voyager 40th Anniversary: Summer of '79

This article originally appeared on Paul Schenk's blog and is reposted here with permission.

The Voyager launch 40-year anniversary triggered a search for and rediscovery of my olde photos from Voyager, reawakening dormant memories. It has also strengthened the realization of how intimately my own path has been linked to this grand adventure and to the completion of the Voyager legacy achieved by New Horizons at Pluto. Certainly suitable for a new blog. Emily Lakdawalla also asked recently if I could write a blog about Voyager and it made sense to merge the two ideas. What follows is a very personal story, not a rehash of the mission. I was not party to the development of or decision making on the Voyager project and my actual contribution was minuscule (putting it gently). Nonetheless, participation in Voyager as a young student was both enlightening and a personal high point that has been surpassed only once. The mission itself (kind of a second Apollo) helped launch a few careers of its own over its 12 year duration, mine included. Maybe there are some lessons in this experience for aspiring young scientists and engineers out there?

Summer of '79

It has been a most eventful past 2 years. The remarkable voyage to Pluto two summers ago was a trip to one of the loftiest summits imaginable and I am most grateful for that opportunity. My voyage to Pluto began 38 years ago this summer (if you don't count the first 20 years growing up in the 1960's Space Age collecting newspaper clippings and making plastic models). This is my story and how I got from there to here.

In the cold winter of February 1979, North American winters were really winters, the north polar ice cap was still formidable and Alaskan glaciers had not yet begun to melt, and our people believed real evidence when they saw it. I was a college student in Buffalo, New York. I was also a backyard astronomy with a standard 2-1/4 inch refractor; and many a cold night was spent on a cold seat with the snow crunched beneath my boots.

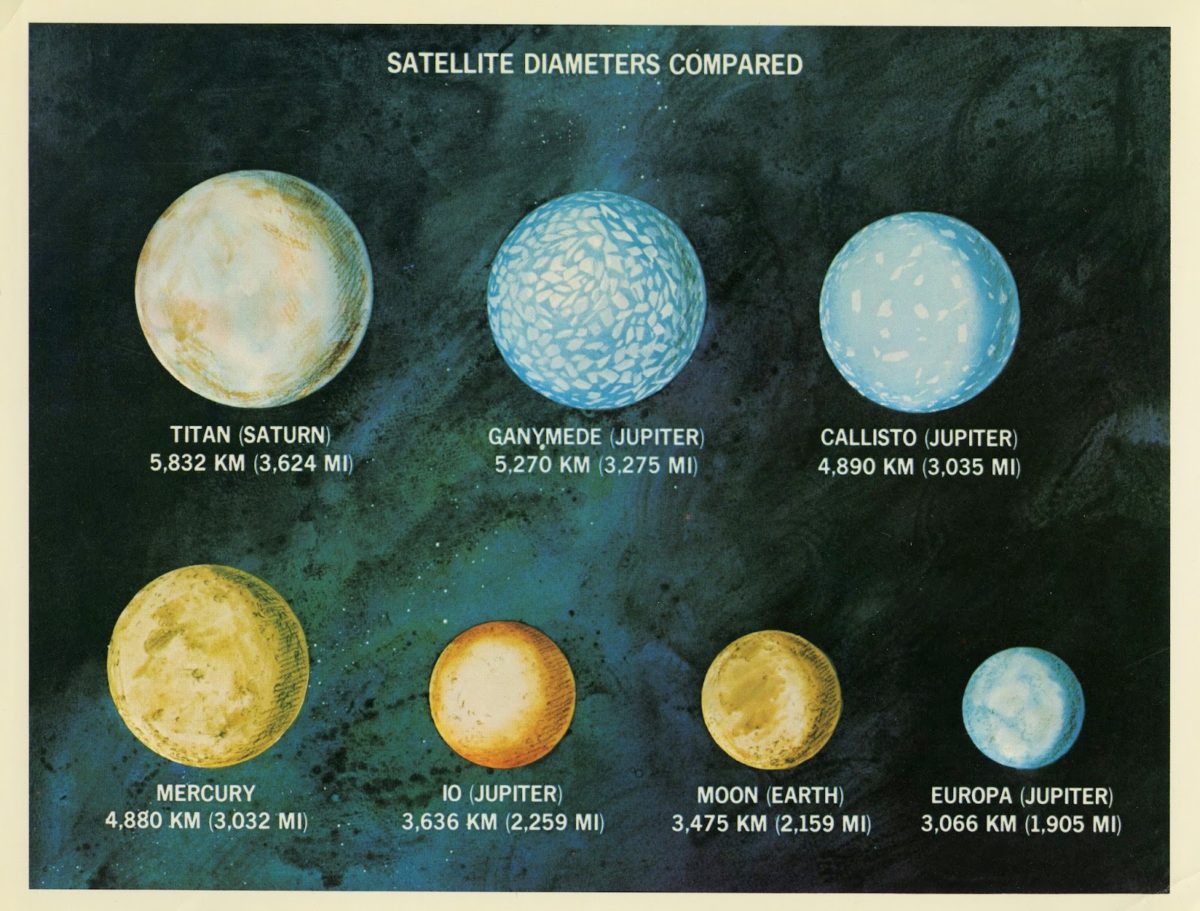

Then, the moons of Jupiter were dusky points of light. No-one knew what they might be like, as this early Voyager diagram shows. This, and my future with it, were about to change radically. I was in those days what would be called a space groupie. I built all the plastic Revell models of the Saturn V rocket, Gemini and Apollo, and collected scrap books full of newspaper clipping of news reports of our national space program, dating back to Apollo 1. Yes indeed, in those days we got much of our news and information from newspapers, sheets of paper with type on them that were delivered to your door! No internet and the none of the propaganda that now plagues it. Several pages of this scrapbook were devoted to planetary exploration, including Mariner 9 and Viking at Mars. One page of clippings was reserved to Voyager, a mission started in 1972. This vast icy mysterious uncharted realm of the giant planets had began to capture my imagination. Lesson 1: follow your passions! Then, the moons of Jupiter were dusky points of light. No-one knew what they might be like, as this early Voyager diagram shows. This, and my future with it, were about to change radically. I was in those days what would be called a space groupie. I built all the plastic Revell models of the Saturn V rocket, Gemini and Apollo, and collected scrap books full of newspaper clipping of news reports of our national space program, dating back to Apollo 1. Yes indeed, in those days we got much of our news and information from newspapers, sheets of paper with type on them that were delivered to your door! No internet and the none of the propaganda that now plagues it. Several pages of this scrapbook were devoted to planetary exploration, including Mariner 9 and Viking at Mars. One page of clippings was reserved to Voyager, a mission started in 1972. This vast icy mysterious uncharted realm of the giant planets had began to capture my imagination. Lesson 1: follow your passions!

By late 1978, having flunked out of our Fine Arts program, I had discovered geology, and it was fascinating. I was blessed by the guidance and mentorship of one Dr. Carl Seyfert, author of the text book on Earth History and Plate Tectonics whose father discovered Seyfert galaxies. Carl had that ‘fire in the belly,’ that genuine enthusiasm for science, logic and curiosity that a young undergraduate was so easily infected with. In Autumn of 1978 a flyer was posted on the department bulletin board announcing a national Summer Intern Program in planetary sciences. It didn’t take a genius to figure who in the department was going to apply.

On 27 February, 1979, a letter arrived with an invitation to go to JPL in Pasadena in July of that year as a Summer Intern. There was much rejoicing. Truth is I don’t really recall much of that day except that it was so cool to be selected that I kept the letter and its envelope. I showed Carl and he was very pleased. I wanted to go immediately and was a little disappointed I could go to the first big Voyager event. Voyager 1 was barely a week out from Jupiter and the great discoveries of volcanoes on Io and fractured terrains of Ganymede were very soon to enter my scrapbook.

This would also be my first adventure outside the western New York – Pennsylvania region I had grown up in. I arrived at LAX a rather naive young man after his first solo flight who promptly spent most of his pocket money on a cab ride to Pasadena. Ouch. Despite that, my continued fondness for Pasadena, a charming suburb of LA spread out beneath the San Gabriel Mountains, dates back to this special summer.

Us three Voyager interns all arrived around July 5 with less than one week before the second Voyager encounter with Jupiter. Later I would learn that Voyager did not have many interns and we were quite fortunate to participate in these unforgettable events. We were instructed to go direct to Caltech student housing as we were going to be staying in undergrad dorms. Ricketts House was ours. I still remember exploring its hallways, sitting rooms, and pinball parlor. While the halls and such have not changed, some things have. The campus cafeterias are completely unrecognizable as is the 21st century cuisine, no longer the old 1979 fare.

Not many stories are remembered. Most students had left for the summer. I was introduced to home-made tacos here, and often used the outdoor pool across California Ave., now being remodeled I think. I remember waking one morning to what sounded like cannon fire only to find that a 20' long steel tube had been erected in the courtyard outside my window and students were firing tennis balls into the surrounding neighborhood with it. Engineering students probably.

Voyager was in fact a sort of Frankenstein mission, reassembled from the dead remains of a much grander concept, appropriately named the Grand Tour. Grand Tour was conceived in 1966 as a 4 probe mission to the 4 gas giant planets plus Pluto, all in one "shot." The 2 Voyagers would instead visit Jupiter and Saturn and if lucky one would go on to Uranus and Neptune. Pluto was left in the cold. For now.

I was assigned to the Science Investigation Support Team (SIST), which was tasked with implementing the designed for the various observation plans of the 11 or so Science Teams. I was NOT going to be assigned to the imaging (or any other) science team, as the Viking interns had been back during the Mars landings in 1976. But I didn’t care a whit; I was in the center of things, part of the great adventure, barely 20 years old, naive and eager.

Our first day at JPL was to get badged and introduced. I was assigned to work with Dr. Ellis Miner, one of the nicest individuals I've ever worked with. He was in charge of planning for the Saturn encounters in late 1980 and 1981 (Saturn had not been visited by any spacecraft at this point). His assistant was Jude Montalbano (now Diner) and they would be my mentors during the Summer of 79. I would get to know many on the Voyager team, including the coordinator with the Infrared Science Team, Linda Horn (now Spilker), who is now the Project Scientist for the Cassini orbiter mission at Saturn!

So what does a 20 year old undergraduate student with no experience do when they join a major space mission about to reach one of its main objective? He gets to know the copy machine very well. In essence I was put to work as a “gopher,” a contraction of “can you GO-FOR this or can you GO-FOR that?” In those days a lot of work was done on paper and large print-outs, especially for quick-look analysis of instrument performance and transmittal of information between project sections. I loved it. Every minute was an exposure to something new and I got to see how how projects like Voyager actually worked, behind the press conferences. I also got to see new data as it arrived; we all got to see the images live as they were received and displayed on the TV monitors stationed around the lab.

It wasn't all work. After the main Jupiter encounter phase had ended us student types could afford to take some weekends off and explore the region. Day trips included mineral collecting in the Mojave and near Palomar (I still have most of the specimens including ulexite and tourmaline), the beach, LAs famous amusement parks, a few concerts, even a day trip to San Francisco on my own. Most of the time we ate on campus or went into town along Lake Ave. for eats and stuff. Olde Town Pasadena was a run-down area and its restoration had not started yet.

This type of work continued for a few weeks until the critical activity of Jupiter encounter receded. Then we began work on my task for the rest of the Summer. I was going to make maps of the major Saturnian moons, in this case to map out where the images planned for these as yet uncharted moons were going to line up on the surface. The goal was to make sure all longitudes were covered and that there were no gaps in the planned coverage that would need to be fixed. After all, there were no plans to return to Saturn at that point and Voyager was it.

In 1979 Macintosh computers did not even exist and computer time was expensive and restricted to key tasks. How were these maps to be made? Out came the graph paper, rulers and protractors. We did not need precision maps, just simple maps that showed the coverage areas so the plan could be updated to fix any gaps. Taking advantage of simple concepts such as emission and incidence angles, I was able to map out where the less shadowed and the more shadowed areas of each image would plot on the global map; and the shadowy areas would have the best feature definition. As it happens, these maps were good approximations of the maps Voyager would ultimately acquire. Not bad for protractor and graph paper. I learned some simple but basic truths about mapping that summer, tho my interest in maps had always been there.

I had no idea in 1979 that I would eventually be making true global maps of these moons years later with the real data from Voyager or from the as yet unconceived Cassini mission, which is soon to draw to a close in September 2017.

That Summer of 79 was the central foundation of all that followed, revealing the outrageous diversity and complexity physical, chemical and geologic processes going on the Outer Solar System. Jupiter overturned all our expectations about icy moons being cold relics of ancient times (remember the first chart at top?). At each of the planetary systems that Voyager explored new things were discovered and yet more wonders of nature unraveled. From the rings of Saturn to the storms of Neptune we were amazed. We were not prepared and Voyager at Jupiter was the key to opening up our imagination.

That Summer of 79 was also my foundation, the beginning of my own long and winding road that led to Pluto and hopefully beyond. I had no idea as I opened that letter what path lay in front of me; there would be many odd detours, wrong turns that became right turns, and even a little bit of good luck. Only the Pluto Summer of ’15 could match the excitement and wonder of that Jupiter Summer, but at the same time there was the very real sense that I was were I was supposed to be, and that I had been in training for Pluto for almost 40 years. That summer remains fixed in my memory as a grand event and the start of it all.

None of this happened by accident. Alan Stern tells the story how at the time of Voyager's last encounter, with Neptune in 1989, a small group of scientists and engineers got together with the determination to finish the Voyager/Grand Tour plan and get to Pluto (still the only other object beyond Neptune known). Only 12 years later, a team and a project had been selected for Pluto and New Horizons was born. I played a modest though important role in that final step. Years later at Pluto encounter I think it is fair to say that there was the very real sense that we were indeed finally completing the original Grand Tour design by going to Pluto.

Similarly, when I was a graduate student I could envision no other job than to map and understand the icy moons that orbit the giant planets. There were many obstacles and many opportunities, none of which could have been taken advantage of without the resolution to make it happen. Determination does mean much without the stuff to back it up and that means doing the best possible work; making yourself indispensable.

Sometimes a little help is useful too. I was blessed with two great advisors during my college days, as well as working with Ellis and Jude on Voyager. While I have certainly published a fair number of papers and discoveries, it was those skills in map making, initiated as a Voyager intern, honed through practice and experimentation, and built on the shoulder of giants (Alfred McEwen comes to mind) that made it possible to work on New Horizons and build those beautiful mosaics of the distant objects ever mapped. Thank you NASA!

There are other memories of the Summer of 1979 worth noting. Each new image from Voyager was flashed up on small black and white TVs scattered across the Lab, and it was easy to follow the encounter as Jupiter loomed larger on our monitors with each passing day. It is difficult to imagine a better time to be involved in exploration. I remember vividly when the first high-resolution images of Europa appeared on our monitors. Voyager 1 had not seen Europa well so this time Europa was the big new story. We were in a small staff meeting of about 5 or 6 people, and the images were due sometime around noon if I recall correctly. We all looked up at the appointed time and there was this strange looking sphere with all sorts of crazy lines on it. They were not the best images that the Voyagers obtained at Jupiter in terms of resolution, but they were some of the most important. The images showed about 25% of Europa and revealed an alien landscape that looked like a cross between a cracked Easter egg and a Jackson Pollock painting. There was no clue that day that this image was going to figure prominently in future developments.

When I returned to Buffalo, Carl and I talked about the summer and being on the Voyager project. I gave a lecture for the department on the experience. I also had the enthusiastic support of Professors Jim Orgren and John Mack. Carl and Jim are gone now and while I was a frequent return visitor and was always happy to meet with my old professors when I visited Buffalo, these visits stopped around 2002 and I haven't seen them since. It is always good to keep in touch with those who have helped you on your way.

Probably the most important chat I had with him was sometime in October that year. Carl and I were looking at the color view of Europa above up on the projector screen in the geology classroom. At first glance the pattern looks hopeless. Myriad crossing lines with no seeming sense or pattern. During this chat I noticed a peculiar pattern in one area of "wedge-shaped bands." There were a set of "piercing points," a structural term to refer to older features broken when a lateral fault in the crust displaces the crust either side of the fault. Lateral movement was something only known on Earth and indicated the icy shell of Europa was moving around. We both understood intuitively what this meant.

We called it "plate tectonics," for which we caught some flak (!), and indeed it would prove to be a Europan version of the dynamic convective process we see on Earth causing earthquakes and volcanic chains. I confess that Carl, an expert of sorts on the relatively new field of terrestrial plate tectonics, understood more of what the geophysical implications were for the interior, me being a mere student, but it was clear to him that this was important enough to present and I gave my first presentation at a science conference at AGU in Toronto (a two-hour drive) the following May.

The rest of this story is more complicated and worth its own blog. It took 9 years to get that article published (Icarus, 1979) and in that time I learn the rest of my craft, finishing graduate school at Washington University in Saint Louis, where I met professor Bill McKinnon, to who I owe everything else. But more on that later.

CODA

Two years after my first Voyager Summer, I was invited back to be part of the Voyager 2 encounter with Saturn in the summer of 1981. I was now a graduate student at Northern Illinois University. I don’t remember much about that summer, except of course Saturn, looming larger in our monitors each day. I was working for Linda Horn (now Spilker) on the Voyager IRIS infrared detector. 35 years later Linda would become the Project Scientist (kinda the boss) of the Cassini project now orbiting the ringed planet!

The big day in 1981 was August 25, with our best moon and ring images, and the pass behind Saturn and through the ring plane. If successful the first ever visit to planet Uranus was a go. This was scheduled right near midnight local time, as was my habit I stayed up late on lab to experience the event. The time arrived for the lock onto signal, but within minutes people were saying there was a problem. The signal arrived on time but the telemetry revealed that several things were not as planned. Not only was the scan platform pointing the cameras fouled up, but the hoped for Uranus encounter 3 years later was now at risk. Experts on the project focused on understanding the problem, but there was considerable relief across the lab when Saturn returned to our monitors 3 days later, and with more testing and validation Uranus was on!

Three and a half years later I was a graduate student at Washington University in St. Louis, under Dr. Bill McKinnon. I had hoped to go with him to experience this one too, but I was having a lot of trouble passing my degree qualifying exams and was not allowed to go. On the morning of January 28, four days after the encounter, I awoke to see if CNN was reporting any new images or discoveries (still no internet), only to see that Challenger had been destroyed. It took several days for the emotional numbness to dissipate as we all slowly went back to our studies.

Flash forward 3 more years and I am now a post-doc at JPL, back where it all started, and 10 years later in the summer of ’89 we were writing the end of the Voyager story, as far planets were concerned. I was not part of the project this time, but with TV monitors everywhere the entire lab was again a witness to the unfolding drama of Neptune, its storms and it large moon, Triton. We did not even know its size as the summer began but eventually we saw the bright icy disk and word spread that they had a diameter (which of course was further refined as we got closer). With Bill in town to be part of the celebration, which was what it became, some of our friends on the project (for lack of a better word) “snuck” us into the imaging team rooms where we had a front seat at the encounter. A day later, Chuck Barry performed on the JPL Mall that evening as several thousand employees gathered to celebrate, and he performed “Voyager Be Good” if memory serves.

So in a very real sense, Voyager was central to my career, and shaped what I do today. An example is New Horizons. The mission to Pluto, with a stop-over at Jupiter, is in a very real sense Voyager 3. It completed the original goals of the Grand Tour, delayed and hence with better remote sensing instruments, but a completion nonetheless. We did not know about the thousands of other icy bodies in the trans-Neptune region back then, but the amazing discoveries at Pluto seem to be telling us that it is going to be region full of surprises; every reason to go back and see as much of the Kuiper Belt as we can.

As protractor was put to paper 38 years ago this summer, did I dream that years later I would actually be making global maps of these moons from the real images, either from Voyager or from the later Galileo and Cassini orbital missions? I'm not sure, but I had no clue that the skills I began to learn in making those simple maps would put me directly in line to make our maps of cold distant Pluto (and subject of our next post)! Not only was the Voyager cycle completed at Pluto but the path from those early ruler-and-protractor maps to global mapping of Saturn's moons and Pluto/Charon was also now complete.

Emily, in her request, asked me to keep young scientists in mind. As you can tell, that intern Voyager Summer of 79 left a lasting impression. Hoping to avoid the error of being lofty and pontifical, let me close with a few thoughts. Seize opportunities. Done successfully and enthusiastically, such gifts are stepping stones to higher things. Whenever I mentor a Summer Intern at the LPI I look for young people with talent who have had no prior opportunity to test themselves and see what they can do, much like a 20-year out of Buffalo 38 years ago. Remember to thank your mentors years later. I was very fortunate to have several! Follow your passion, follow your talents. I can’t integrate my way out of a paper bag but I know how to make a good map, and I know plate tectonics when I see it. Mentors should encourage native talent as much as possible. Always be inquisitive, and whatever you do, do it extremely well. Never accept the easy answer until it is tested. Double check everything, attack a problem for all perspectives and with all relevant data sets. If you need help, seek it out in others and work together. In this way a simple story about a landslide on Io helped unlocked the puzzle of how non-volcanic mountains can form on a volcanic world. A little arrogance is useful but so is a little humility. Keep the arrogance inside; nobody likes seeing it. Beg for mercy when you show up 5 minutes late for your first conference presentation as your advisor’s student (think John Belushi and Carrie Fischer, Blues Brothers). Enjoy it! Discovery is a real rush so seek it out and make it happen.

Happy Anniversary Voyager and thanks!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth