A.J.S. Rayl • Oct 07, 2013

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Roves to Solander West, into Winter Campground

Sols 3415 - 3444

The Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission stepped up preparations for the coming Martian winter in September as Opportunity rounded the northern tip of Solander Point and drove into what will be her campground at Endeavour Crater for the next six months or so. It's been nearly a year in the planning. Now, from the rover's first look around, this winter could turn out to be one for the books.

Harsh beyond belief, winters on Mars are life threatening, even for robots. Opportunity must endure constant, sometimes radical fluctuations in daily temperatures, not to mention survive temperatures as low as 100 degrees below freezing, all of which is really tough on her metal parts. Of course, the veteran rover has proved its resilience many times over while exploring this sub-freezing planet and the MER ops team is as experienced as they come – plus Mars, as they like to say, is "cooperating." Even so, this will be the Opportunity's sixth Martian winter.

September 2013 marked nine years and nine months since this rover bounced to a landing and set out on a 90-day mission, and her solar panels are covered in dust. Surviving this winter is all about location.

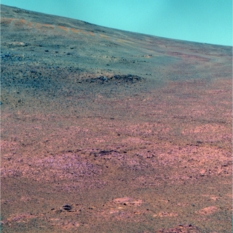

Rounding the Point

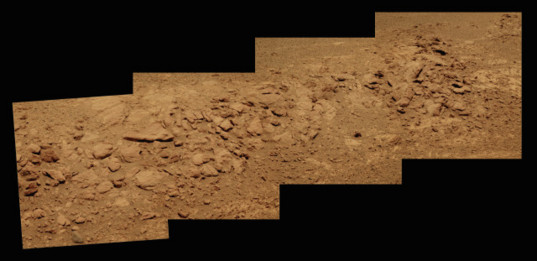

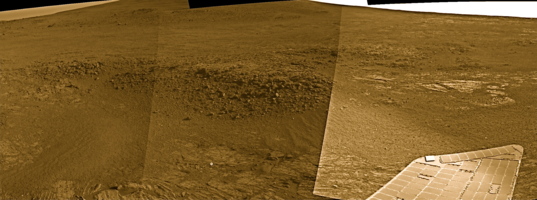

It looks like blue skies for Opportunity as the veteran rover confronts its sixth Martian winter. The rover took this picture with her panoramic camera (Pancam) in mid- September, as she was rounding the northern tip of Solander Point. She headed into her sixth Martian winter campground on the western side of this section of Endeavour Crater's eroded rim, partially visible as the rise in the background. Presented here in false color, as processed by the Pancam team, this is part of what will be a larger presentation of the rover's view.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU

Along the western side of Solander Point, a rich assortment of north facing slopes bears good tidings. Ranging from 5-degrees to 20-degrees, the slopes offer havens where the rover can position its solar arrays directly toward the Sun in the northern sky and continue to produce enough to make it through. And so, despite Opportunity's age and dusty solar panels, "the prognosis for winter is good," said Scott Lever, MER mission manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), mission control for all of NASA's Mars rovers. And not just "good" in terms of survival.

Opportunity, if all goes as projected and planned, will be mobile and actively working throughout the brutally cold season …. unlike the last Martian winter when this rover, for the first time, had to park and conduct limited science from a solitary position. "This winter we should be able to continue to drive and move target to target," Lever said. "That is our goal."

It gets better. Ray Arvidson, the MER deputy principal investigator, has already pinpointed an area at Solander Point that may be harboring more science "gold," and Opportunity has arrived at her winter haven with time on her side. The Martian winter is still on the horizon.

In the southern hemisphere of the planet, where the rover is exploring, winter solstice falls on February 14, 2014, so it is currently still fall at the ancient, 22-kilometer (13.67-mile) Endeavour Crater. That gives the MER team a couple of months to pack in as much science as possible and at the same time find prime slopes where the rover can rest between assignments and soak up the best of the winter Sun.

The mission has been preparing for the coming Martian winter for nearly a year. A group within the MER team, known as the Endeavour Strategic Planning Group, has spent months scrutinizing orbital data, especially pictures taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which pretty clearly show the rolling, north-facing, sunny slopes of the western side of Solander Point.

With HiRISE images and digital elevation maps before them, the strategy group has been considering potential locales and strategizing targets for the rover's winter science campaign, trying "to weave" into their planning "optimum science goals with optimum [tilt] positions for the rover engineering concerns," said Lever, who heads the group. "We strategically planned Solander Point, in order to allow the rover to maneuver from science target to target throughout winter."

Since Opportunity has strolled into her winter campground, the picture postcards and panoramas it is sending home will feed into the group's plans, along with the continuous flow of orbital data. Within some of that orbital data, Arvidson, who serves as the strategy group's liaison for the MER science team, has isolated a location here, some 200 meters from the rover's current location, where he believes evidence of clay minerals wait to be uncovered.

Opporunity's trekking grounds

This image, taken by the HiRISE: High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) is labeled to show Cape York, Opportunity's last neighborhood, and Solander Point, the part of Endeavour Crater's eroded rim it is exploring. The robot field geologist geologist rounded the northern tip of Solander Point in mid-September and will be spending its sixth winter on the north-facing slopes on the hill's western side.NASA/JPL-Caltech/UA

For the next several weeks, Opportunity will be in recon mode, surveying slopes and potential science targets. "We want to do a reconnaissance of this area where I think the clay minerals are before winter solstice, to see if there are good northerly slopes nearby," said Arvidson, who is the James S. McDonnell Distinguished Professor at Washington University Saint Louis. So, it will be a while yet before the team decides exactly where and how this rover will spend its sixth Martian winter.

Opportunity first pulled up to the northern part of Solander Point from the inboard or crater side in August, following a two-and-a-half-month journey from Cape York. Like Solander Point, Cape York is a section of the broken rim of Endeavour. Rising well above the surface, these rim sections contain rocks and remains from the Noachian Period some 3 to 4 billion years ago, when Endeavour Crater was formed, and when Mars was thought to be warmer, wetter, and more like Earth.

Opportunity and the MER science team made history earlier this year when they ground-truthed the presence of clay minerals detected by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument onboard MRO, in a couple of those ancient rim rocks at Cape York. CRISM, which is designed to search for evidence of past and present water on Mars, picked up the signatures for phyllosilicates, specifically smectite clay minerals, in Endeavour Crater's western rim in 2008. Then, in 2012, while the rover was exploring Cape York, Arvidson, also a co-investigator on CRISM, did some research on additional data taken with the orbital spectrometer, and narrowed one location to Matijevic Hill.

Within months, the MER scientists identified a rock at the foot of Matijevic Hill, dubbed Whitewater Lake, as part of the oldest rock unit Opportunity had ever encountered and the location of the phyllosilicates. Further investigation in a rock called Esperance, located higher up on Matijevic Hill, led the scientists to conclude that at least two types of smectite clay minerals had formed there long ago.

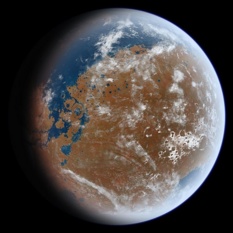

Noachian Mars imagined

Opportunity is currently roving over Noachian terrain at Endeavour Crater. This is an artist's impression of what the Noachian Mars might have looked like. Late Hesperian features (outflow channels) are shown, so this is not an exact impression of Noachian Mars, but the overall appearance of the planet from space may have been similar to the impression and to Earth. The artist, Ittiz, created this image using knowledge of Martian geologic history and data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter, an instrument on the Mars Global Surveyor, which was de-commissioned in January 2007.Ittiz

Ground-truthing the presence of clay minerals was a huge achievement for MER. For starters, finding phyllosilicates was not on the list of science objectives for MER. Rather, it is a discovery objective on Curiosity's agenda. More importantly, clay minerals are evidence of past water that is more neutral, more like the drinkable water we know on Earth, as opposed to the highly acidic past water for which Opportunity and Spirit previously found plenty of evidence. And, most significantly, near neutral water is evidence that an environment that could have fostered life may once have been present where Endeavour Crater is.

Arvidson's latest finding of a clay minerals site along the western side of Solander Point and Opportunity's eventual ground-truthing of that area will certainly expand on that water story. That is significant research. But it appears there is a lot more for the rover to find in this section of Endeavour's eroded rim.

Size does matter, geologically speaking. Where Cape York exposes a few meters of vertical cross-section through geologic layering – which is how geologists "read" a region's geologic history – Solander Point by comparison exposes "about 10 times as much," according to Arvidson. How could there not be more history waiting to be uncovered at Solander Point?

At the beginning of September however, Opportunity was in the midst of a science campaign on younger, ancient outcrop targets on the eastern side of Solander Point, near where it first pulled up to it this section of the crater's rim. Homing in on rocks that are part of an escarpment or small cliff that extends for a couple hundred feet toward the Point's northern tip, the robot field geologist followed the intriguing formation north toward the tip, checking out a handful of rocks as it headed toward the winter campground.

The escarpment separates the apron area that surrounds the Point, known as the Bench, from the Point. It is a boundary or contact, as the scientists call it, between different geological periods. "The Bench is the oldest sedimentary unit Opportunity has found, which we call the Grasberg unit, and at Solander it's draping right up against Endeavour rim materials, and it's dipping pretty steeply," Arvidson said. From the data received and analyzed, the general scientific consensus is that the escarpment and the rocks Opportunity examined during the first half of September are a part of the Bench that hasn't been quite as eroded as the rest of the Bench, he said.

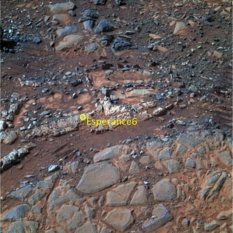

Esperance

Opportunity studied Esperance in April and May 2013, using its cameras and its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS). From the data the rover sent home, scientists were able to determine that Esperance's composition is higher in aluminum and silica, and lower in calcium and iron, than other rocks the rover has examined during its exploration of Meridiani Planum. The scientists eventually inferred that what they had found were signs of a more an aluminous clay than the clay minerals ground-truthed previously at Whitewater Lake, in the group of minerals known as montmorillonite, which usually form during intensive alteration by water. "We don't know the mineralogy, just the composition, but the composition is pointing to a montmorillonite," said Ray Arvidson, who now believes there may be more of this aluminous clay at Slander Point. The view of EsperanceNASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

From the modern wind blown ripples and sand that cover the Burns formation of bedrock over which the rover traveled until it reached Endeavour, Opportunity began going further back in Mars' geologic time when it first discovered the Grasberg unit shortly after arriving at the big crater. Higher up, within the jumble of rocks, slabs, and materials that make up the Matijevic Hill section of the Cape York rim segment, the robot field geologist found two more distinct rock units, both older than Grasberg. These stratigraphic layers – one dubbed Shoemaker, formed of breccia rocks, and the other called Whitewater Lake, defined by flat, light-toned rocks with a dark coating or rind on them – took the rover back to the Noachian Period.

Opportunity found the contact between the Whitewater Lake rocks, which are "pre-existing," and the overlying breccias, which are "probably Shoemaker breccias, probably from the impact event," according to Arvidson, at both rim sections. "That's one contact within the rim materials, from pre-existing rock to ejecta put on top of it."

Although this rover has already ventured further back in Mars geologic history than anyone on the science team ever dreamed possible when the mission began, Solander promises the journey will continue. The MER scientists are working overtime to keep pace with the rover's non-stop stream of findings. Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University, and Arvidson each have papers on Whitewater Lake's clay minerals in review. Another dozen to 18 papers, all emerging from data collected by Spirit and Opportunity, are being submitted to Journal of Geophysical Research Planets.

Meanwhile, as the fall season advances on Mars, the Sun is beginning to rise and set lower in the sky. The Martian days or sols will slowly become shorter in the planet's southern hemisphere and the amount of sunlight available to the solar-powered rover will decline steadily until the winter solstice in mid-February. Opportunity is already feeling the effects, said Ashley Stroupe, MER rover planner. "We are starting to see the winter power issue and are looking now for slopes to boost our energy."

During September, the rover's dust factor – the measurement that gauges how much sunlight penetrates the accumulated dust on the solar arrays and is transferred into energy – deteriorated "a little more" than the engineers at JPL had predicted in August, reported John Callas, the MER project manager, of JPL.

The MER ops team is responding, yet they remain confidant in their rover and in their projections. "There have been better dust factors in previous years when the solar panels were cleaner, but the model for Opportunity's dust factor this year matches the past couple of years pretty closely, that is, the pattern appears similar in the way it curves year over year," Lever said.

NASA / JPL-Caltech, Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Follow the scarp

During the first part of September, Opportunity was investigating rock outcrops along an escarpment – scarp, as geologists call it – on the eastern side of Solander Point. This scarp is a boundary or contact between the Bench, which surrounds the eroded crater rim section, and the rim. The pictures that went into this image were processed in near true color by Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, planetary outreach godsend, and blogger of many celestial things. For more of his work on MER, see: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/Dust is something no Earthling can control or necessarily predict, not yet anyway. The good news is that both the rover's dust factor and the Tau, or amount of the dust in the atmosphere, are most stable during wintertime. Nevertheless, "we need to get on to steeper slopes a little earlier than last planned, by a few weeks," said Callas.

The steeper slopes required, ranging from 5 degrees to 15 degrees, would seem to be almost effortless for Opportunity by comparison to the 30-degree tilt Spirit parked on at Home Plate for her fourth Martian winter. Indeed, Opportunity's handlers are openly optimistic that the robot field geologist will sail through the coming Martian winter with flying colors and no serious issues. Still, this mission didn't get to where it is without a fair amount of caution. "We continue to prepare and refine what we're doing for winter based on new ground data and all the other considerations," said Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering, at JPL.

CRISM map of Endeavour western rim

This is a geologic map of a portion of Endeavour Crater's western rim. It is based on the data taken by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), a visible-infrared spectrometer onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. This instrument searches for mineralogic indications of past and present water on Mars. A discontinuous ridge that runs north-south shows exposed basalt (marked in blue) and clay minerals (marked in green).NASA / JPL-Caltech / JHUAPL

Despite her age, arthritic shoulder and right front wheel, and two out-of-commission mineral detectors, Opportunity is "doing great," Nelson reported. "She has been remarkably trouble free. We have had a couple months now with essentially nothing going wrong."

Although the rover continues to drive mostly backwards because of that stiff right front wheel, and has to drive with her arm partially deployedbecause of the broken shoulder joint, which does look a little awkward, the rover that loves to rove is roving well. "We've had great driving and it's been consistently what we expect," said Stroupe. "We've been very lucky."

"The rover is going through a period of great health: the mobility system is doing well and we have had no appearances of any Flash memory problems," Callas summed up.

The MER ops team is just beginning to get the downlinks of Opportunity's first pictures of her winter campground. On first look, the scientists and engineers like what they're seeing. "It's living up to what we hoped it would be," said Stroupe. "We are definitely seeing good northerly tilts there that should be great for the winter and we're optimistic that the terrain will be pretty friendly."

While they knew from the HiRISE images that this side of Solander featured the desired north-facing slopes, which is what led Opportunity to this site, there is nothing like ground-truthing. "We do stereo imaging everywhere we go as a matter of course," said Lever. "The rover planners will be studying the ground-truth images the rover is taking now to find the best tilts – 'lily pads,' as we call them – to maximize energy throughout the winter." The scientists are looking at them for interesting targets.

"There are a lot of lily pads around some great geology where the rover can generate energy," Callas said. "The idea is to hop from lily pad to lily pad."

Of course, this is Mars. Anything can happen anytime. But as always, the MER team on Earth will have Opportunity's back, err bogie. "We have risks all the time, and Mars could throw us a curveball any day, but being able to get on good tilts is helpful in assuring us. We're hopping now," Lever said at month's end. "And we think we can do science at a 15-degree northerly tilt even in the depths of winter without any trouble. It will be more limited than in summer, but it's not bad."

As September turns to October, Opportunity is hugging the edge of Solander Point, sitting on the contact between it and the Bench, snapping the hundreds of pictures it takes to produce a color panorama of its sixth winter campsite. Then, she will motor on, looking for "juicy" slopes, as Lever described them, close to interesting science targets, like where Arvidson believes clay minerals from eons long ago await.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

When September dawned at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was investigating a rock target, dubbed Coal Island, on the eastern side of Solander Point. The outcrop is part of an exposed escarpment – or small cliff – that caught the scientists' attentions. It meanders for some 80 meters (about 262.47 feet) along the northern part of the Solander Point rim segment toward the tip, and is a boundary or contact between the Bench, the apron area that surrounds the base of Solander Point and the older Noachian rocks in the rim itself. The scarp, as the MER geologists call it, is an obvious and intriguing formation to check out.

So the plan for September called for Opportunity to follow the scarp to the tip of the Point, checking out a number of rock outcrops along the way to determine if they part of the Bench or something else. Following that, the rover would head around Solander Point's tip and over to the western side of the rim segment, where HiRISE images show winter friendly, north-facing, sunny slopes that offer the rover a number of safe havens, even during the depths of winter.

Overview of Endeavour Crater

This image, taken by the University of Arizona's HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the sites where Opportunity has been and is going. It was colorized and labeled by Stuart Atkinson, of UnmannedSpaceFlight.com, and frequent contributor to the MER Update. Atkinson has been following Opportunity's path to Endeavour in a blog called The Road to Endeavour, which you can visit here: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / S. Atkinson

Opportunity was managing to produce plenty of energy – 365 watt-hours – as the month began, despite the fact that the skies were what some Earthlings might call a hazy shade of winter. The Tau was 0.640. The rover's solar array dust factor was fluctuating from 5.25 to 0.522. Translating, that means the rover was only able to convert less than half the sunlight hitting her panels to fuel, and with fall taking hold, everyone knew it would soon get worse.

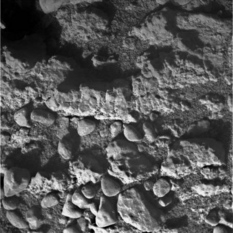

On Sol 3415 (September 1, 2013) Opportunity – with 38.26 kilometers (23.77 miles) on her odometer – began the month at a surface target on Coal Island called Dibbler. After taking a series of pictures with her Microscopic Imager (MI) for a mosaic of the surface target, she placed her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) on the target, following the established scientific protocol to analyze its chemical composition. During next three sols, the rover continued the APXS integrations and also conducted a multi-spectral imaging survey of the scarp by using her Pancam.

After completing work on Dibbler the robot field geologist took some more color Pancam images of the escarpment on Sol 3418 (September 4, 2013), and then the following sol, bumped about 3 meters (9.8 feet) to a new surface target on Coal Island, called Monjon. She then spent a quiet Sol 3420 (September 6, 2013), recharging and taking a routine atmospheric argon measurement with her APXS.

Opportunity started the second week of September on Sol 3422 taking close-up pictures of Monjon with her MI for a mosaic. As usual, after the imaging session, she placed the APXS on the same target for an overnight integration. The next sol, the robot field geologist offset the APXS for another integration, documenting the repositioning of the instrument with a MI picture, and then used her Navigation Camera (Navcam) to snap a seven-frame panorama.

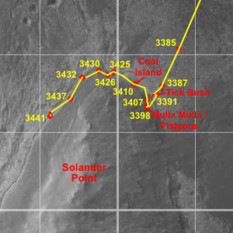

Opportunity route map

This route map, produced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of Unmanned Space Flight.com (UMSF.com), traces Opportunity's travels around Solander Point's northern tip and into its winter campground on the western side of this sections of Endeavour Crater's eroded rim. Tesheiner creates his route maps, which are regularly featured in the MER Update, from images taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and then tracks the rover's drives as it explores and labels them.NASA / JPL / UA / E. Tesheiner

On Sol 3424 (September 10, 2013), Opportunity conducted another evening APXS integration on Monjon. The following morning, the rover got up and took a close-up Monjon with her Pancam and a full color picture of the Coal Island outcrop, then took off on a 25-meter jaunt northwest. The rover stopped mid-drive to take some pictures of a large, triangular outcrop exposure on the scarp the team nicknamed Wattle, and then drove onto the bedrock of the tip of Solander Point.

The rover's examinations of the outcrops on the scarp have convinced most of the MER science team that the Bench represents some of the older materials and that the Burns Formation is sitting on top of it. "Dibbler, Monjon, and the other Grasberg outcrops are all consistent with the Grasberg materials we have seen around Cape York, Sutherland Point, and Nobbys Head," said Arvidson. "Structurally and stratigraphically, they are consistent with the Grasberg materials being the oldest sedimentary unit that formed on top of Endeavour's rim, after the rim was partially eroded down."

Opportunity completed an 8.62-meter (28-foot) sprint on Sol 3426 (September 12, 2013) to close in on the next target, a cobble-sized rock, dubbed Poverty Bush. The next sol, rover deployed her IDD to take some pictures of the Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) bit to assess how many more grinds they may be able to get out of it. That same sol, she collected some routine calibration sky flat images with her MI and then took close-up pictures for a mosaic of Poverty Bush. As usual, the rover placed her APXS on the rock target for a multi-sol integration.

Turns out the RAT is looking good. Gale Paulsen, senior systems engineer, and others at Honeybee Robotics & Spacecraft Mechanisms Corporation, the company that designed and manufactured the RAT, reviewed the pictures Opportunity had taken and downlinked. "We saw no appreciable wear from the previous grind," Paulsen said via email. "All is still well with the RAT."

The next couple of sols were science light. Opportunity recharged and conducted an evening APXS integration on Poverty Bush on Sol 3428 (September 14, 2013), completed a pancam Tau the following sol.

During the third week of September, Opportunity finished work at Poverty Bush and moved on, roving across the tip of Solander Point and over to the western side. After taking Pancam pictures to survey clasts or small rocks in chosen spots, she drove 12 meters (about 39 feet) to the west/northwest on Sol 3430 (September 16, 2013). The next sol, 3431, the rover drove another 22.53 meters (73.92 feet) to another candidate outcrop. "That drive took us from the northern peak and onto the Bench on west side of Solander Point, and then back south a little way," said Nelson.

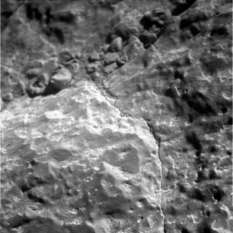

Dibbler up close

Opportunity used her Microscopic Imager (MI) to take this picture of Dibbler in early September. Dibbler is a surface target on Coal Island, an outcrop that is part of an escarpment that extended for some 80 meters along the eastern side of Solander Point, near where the rover arrived at the base of the rim section.NASA / JPL-Caltech

From her position on the contact between the Bench and the western side of Solander Point, Opportunity began Sol 3432 (September 18, 2013) with pre-drive color Pancam imaging of targets Long Nosed Potoroo and Little Red Kaluta, named after tiny marsupials from Australia, courtesy of MER science team member Wendy Calvin. The rover then took pictures for 3x1 matrix of some Grasberg outcrop just to the southwest and then bumped 2.05 meters (6.72 feet) to position herself over the next rock target, dubbed Wally Wombat.

The plan was for her to spend the weekend at Wally Wombat, so on her 3,433rd Martian day, Opportunity took it easy. After recharging and checking the Tau, she conducted a late afternoon, low-sun Pancam sky survey. Then, the rover, still positioned over Wally Wombat, called it a sol.

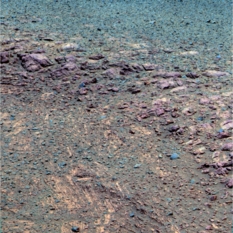

In position and ready to rock, the robot field geologist pulled out her RAT on Sol 3434 (September 20, 2013) and pressed it down on her target. "The rocks here look kind of like pavement in the pictures – like an old Roman road – all broken up into pieces that are relatively flat," said Nelson. The rover brushed Wally Wombat, took the usual MI pictures afterward, and then put her APXS down to try and tease out the chemical components of Wally Wombat.

After rising on Sol 3435 (September 21, 2013), Opportunity shot some pictures of the ridge that runs through Solander Point with her Pancam. Essentially, it was a Solander Point transect collection, looking south-to-southwest, for a large mosaic that will show the different contacts that overlap each other there, among other things. While she wasn't quite ideally positioned to take pictures of the ridge, the robot field geologist aimed her Navcam and snapped a panorama anyway, and then continued the APXS integration on Wally Wombat.

After taking a color Pancam panorama of nearby ripples the robot field geologist, on Sol 3436 (September 23, 2013), took Pancam pictures for a Bench transect, which eventually will be merged with the Solander Point transect that the rover shot previously. She then took some pictures of Agile Antechinus, a vein target in a flat slab of rock that looked like Whitewater Lake, named after another small marsupial found in Australia, and documented a contact between ground formations with pictures for a larger mosaic.

Following that, Opportunity packed up and took off. At the beginning of the drive, she paused to look back at Wally Wombat snapping a full color, 13-filter Pancam image of the brushed target. Then she traveled southwest along the Bench for 32.47-meters (106.52 feet). After the drive, the rover acquired a Navcam 5x1 mosaic and performed an APXS atmospheric argon integration. Her total odometry was 38.37 kilometers (38,370.6 meters, 23.84 miles).

The scarp in false color

On her Sol 3418 (Sep. 4, 2013), Opportunity used her Pancam to take this photograph of the escarpment she studied during the early part of September. It was processed in false color by the Pancam team in order to better show the different constituents of the formation. Monet would have had a field day with this.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Sol 3438 (September 25, 2013) was basically a recharge sol, although Opportunity did conduct a Pancam Tau and a Navcam Tau, to better tease out what dust is on the camera lenses versus in the air, and because two Taus are better than one.

The rover's power production continued to decline as September progressed, with levels dropping from 362 watt-hours around Sol 3424 (September 10, 2013) to 346 watt-hours one week later on Sol 3431 (September 17, 2013) and to 322 watt-hours on Sol 3437 (September 24, 2013). The Tau bounced around slightly during the time, ticking up, from 0.59 to 0.61 to 0.62 during the second and third weeks of September. While the rover's dust factor also fluctuated in September, from 0.51 to 0.52 to 5.0, it was overall slowly deteriorating. As the Tau drops, which it likely will, dust will rain out of the sky and onto the rover's solar panels, further blocking her access to needed sunlight fuel.

"We are getting further away from the Sun and so sunlight is dimming a little bit," reported Nelson. "We are seeing a Tau and dust factor kind of follow our models, so energy is also pretty much as we expected. But we have downgraded our predictions a little bit, so we're going to need to constrain our easterly tilt, as well as our northerly tilt a bit. That should allow us to get through the winter with enough energy to do reasonable science even in the depth of winter," he said.

The objective is to try and keep Opportunity's power production at 250 watt-hours or better, even through winter solstice, said Nelson.

Down on Earth, the MER team had an end-of-sol discussion on September 25th, 2013 to talk about the latest power predictions and where they the rover needed to be – that is, what degree northerly slope Opportunity had to be on as the Martian winter descends and as it bears down. Jennifer Herman, a power subsystem engineer for MER, presented new power estimates and, for discussion purposes, Arvidson then presented a plan for where the rover should be as a function of time, which was "consistent with the new power estimates" and which would "maximize science return."

The bottom line: Opportunity should begin hopping from one 5-degree northerly slope or lily pad to another right away. By mid to late December, the rover shouldbe on north-facing tilts of about 10 degrees. "Then, if we want to do extended campaigns during the dead of winter – in February 2014 – we'll need 15-degree tilt," Arvidson said.

Based on the HiRISE data and digital elevation maps made from all the new orbital data, the MER ops team is confident that those slopes exist. "But it really requires ground mapping with Pancam and Navcam to find the local niches that have the relevant slopes," said Arvidson. Considering that Spirit perched and parked at a 30-degree tilt on Home Plate to survive her fourth Martian winter, a 15 to 20 degree tilt should be easily do-able for Opportunity.

In a worse case scenario, if Opportunity is only able to produce power in the 220 watt-hour range, it would still have enough energy to do limited science, and even driving once or twice a week, Nelson said. "Below 200 is when we get down into survival mode."

NASA / JPL-Caltech

On the road to Solander Point West

Opportunity took the pictures that went into this panorama with her Navigation Camera during the second week of September, just before the rover rounded the northern tip of Solander Point and headed into her winter campground on the western side. You can see the contact or boundary between the Bench and the eroded rim in the foreground, while the ridge in the back is where the rover will be spending its sixth Martian winter.The MER Ops team isn't taking any chances. "We're already starting the lily pad hopping in order to maximize energy for science return," said Lever. "We don't really have to use lily pads right now for spacecraft survival, but it could hurt our science return if we don't. It's our preference now to try to find good science targets on very juicy northerly tilts. We know they're there."

Wally Wombat

Opportunity brushed Wally Wombat with her Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) during the final days of September, not long after she crossed over to the western side of Solander Point. Once her examination of the rock was complete, the robot field geologist backed up and took this image with her Pancam.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Lever and others in the strategy group have been looking at these northerly tilts from afar using HiRISE pictures from MRO for months now. "There are noise patterns that show up in the HiRISE images showing tilt, which give false readings, but Ron Li, of Ohio State University, and his group have software that removes a lot of the pattern noise," said Lever. "So we trust our HiRISE images. They're pretty close and now we are ground-truthing the slopes, and seeing them from the rover's point of view."

With regard to science, the MER team agreed in the September 25th end-of-sol meeting to command Opportunity to "pretty expeditiously" do a recon of the local area, from north to south, looking at possible outcrop targets for the winter science campaign. After that, if it's possible, the rover may well drive the some 200 meters south and west to where Arvidson thinks the clay minerals are before the Martian winter bears down. Since the rover's two mineral detectors are no longer functioning, the team will need time to ground-truth the presence of those clay minerals and winter will certainly give them that time.

Opportunity woke up on Sol 3439 (September 26, 2013), took Pancams of a ripple then drove 35 meters to the southwest, continuing along the contact, to a better position to view the ridge. "That drive took us to the western side of the Bench and in striking distance to move inward toward the ridge itself," said Arvidson.

Comet ISON

This image of Comet ISON was captured by the Hubble Space Telescope on April 10, 2013. During the final weekend of September, Opportunity looked to the skies above and attempted to take her own picture of the comet that may light up the daytime sky in November 2013. At presstime, the images the MER took had not yet arrived on Earth, so stay tuned.NASA / ESA / J.-Y. Li, Planetary Science Institute, and the Hubble Comet ISON Imaging Science Team

During the final weekend in September, on Sol 3440 (September 27, 2013) and Sol 3442 (September 29, 2013), Opportunity attempted nightime observations of Comet ISON. Some reporters have started calling ISON the "Comet of the Century," but Don Yeomans of JPL and NASA's Near-Earth Object Program thinks that is premature.

Currently a faint speck of light moving through the black of space, ISON could light up Earth's sky later this year – or not. Known as a Sungrazer, this “dirty snowball" will fly through the Sun's atmosphere some one million kilometers from the stellar surface on November 28, 2013. If the comet survives the Sun's atmosphere, it could emerge glowing as brightly as the Moon, briefly visible near the Sun in broad daylight, and skywatchers note, the comet's dusty tail stretching into the night sky could draw worldwide attention. But it's as likely to fizzle as it is to sizzle. "Comets are notoriously unpredictable," as Yeomans put it.

No word yet on if the comet is visible in Opportunity's pictures. But don't expect much. "If anything is visible to MER, I heard it should be at best a 3 pixel smudge," Lever said.

On Sol 3443 (September 30, 2013), Opportunity brushed Callitris, a flat, light-toned rock with her RAT and followed that by taking Pancam and MI stereo imaging. She then placed her APXS on the target for the usual integration and said good-bye to September.

As October takes hold, Opportunity will be intently focusing on her surroundings and taking pictures with her Pancam of her winter campsite for the next big 360-degree color panorama. The biggest concern remains the same: dust. "We're not happy with the dust factor right now, but at least it's similar to the last couple of winters," said Lever. "Because it's similar, the rover probably won't be confronting anything super dangerous and we've done what we think is a great job of getting ourselves into a position to be able to drive the whole winter while doing science."

If for any reason, Opportunity's energy really began to slip, the rover could choose to find the best tilt, park, and wait out winter. "But I don't think it's going to be needed," said Lever. "Based on all our estimates and everything we've looked at, I think we will be mobile this entire winter. I really believe," he added, "that we are sitting in a situation now our goal is – pray for dust cleanings and getting through the next winter."

In the meantime, Opportunity has her work cut out for her.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth