A.J.S. Rayl • Oct 04, 2014

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Gets Extension, Returns Killer Panoramas, and Roves onto Mystery Rocks

Sols 3770 - 3799

While the winds of Martian spring blew through Meridiani Planum in September, Mars Exploration Rover (MER) Opportunity reformatted its Flash memory then continued exploring Wdowiak Ridge on the western rim of Endeavour Crater. Even though the Flash-related issues soon returned, the robot field geologist hardly seemed to notice as it sent home two spectacular panoramas, presented the scientists with a rocky Martian mystery, and delivered yet another September to remember for the mission. And that's not all.

The best news of the month broke right on September 4th when NASA announced that it is granting MER its ninth mission extension. That means Opportunity will visit those new breathtaking landscapes just ahead at Marathon Valley, and that one of the most remarkable and beloved space exploration missions in history has another two years to uncover more Martian history and perhaps make a little more history of its own.

"We have a healthy rover, good weather, the funding we need, and terrific science ahead of us," Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University, said during an interview at September's end. "It's continued good times for Opportunity."

It may be hard to imagine Opportunity – the oldest "living" American Martian geologist and most traveled servicebot on another planet – wouldn't rove on for as long as possible, until the last critical bolt holding it together pops out and the rover collapses. If only as a testament to American engineering. Or, because we take care of our own. Or because the knowledge is unfolding on Mars as you read this. The panoramas the rover captured in September – one of Wdowiak Ridge, the other peeking inside Ulysses, a crater embedded in the southern part of the ridge – offer vistas and inspiring images rich with scientific pickings that alone would seem worth continued investment. But space life's not like that.

Every project that is working beyond its primary mission must submit a proposal every two years to NASA. Agency officials, in turn, appoint a Senior Review Board for each mission to determine if continued investment is worth the scientific payoff. In the case of MER, that investment is about $14.5 million annually. The payoffs – including everything Spirit and Opportunity came looking for and more – have been chronicled month-to-month in the MER Update for more than a decade.

Not surprisingly, MER's extended mission proposal, which was primarily produced by Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis, Callas, and Squyres, received "extremely high marks and no major negatives," as Matt Golombek, MER project scientist, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) reviewed MER's review: "Everyone [on the Senior Review board] seemed to recognize the importance of us carrying on at our current pace, so we are overjoyed."

Hoover

Opportunity took this image of the rock dubbed Hoover with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) on her Sol 3796 (Sep. 28, 2014) near the rim of Ulysses Crater. This rock is one of hundreds hurled up from beneath Wdowiak Ridge, by whatever created Ulysses Crater, and one the rover studied in September. "We're finding some real interesting rocks with significant diversity and multiple lithologies," said MER PI Steve Squyres. The Pancam team processed this image of Hoover in false color, which enables scientists to better distinguish the different rocks in the frame.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

So, despite her age, the continued annoying bouts of amnesia and tics with her Flash memory system, arthritic shoulder and front wheel, the future looks as bright as ever for Opportunity. "We're pleased about how it went for us," summed up John Callas, MER project manager, of JPL, the NASA center that is home to all the American Mars rovers. "We're in very good shape for two more years at least of exploration."

During those two years, this robot field geologist may well uncover some of the most significant discoveries ever made on the surface of Mars, including important clues about the Noachian Period some 3.7 to 4.2 billion years ago when Mars was more like Earth, warmer and wetter. Given that Opportunity is the only rover investigating the Noachian Period, the prospect that she may soon be driving back to a time and place on Mars where life may have emerged shimmers on the horizon of thoughts about what lies ahead.

Although scientists have long known that Endeavour Crater formed during the Noachian Period, it wasn't until a year after Opportunity arrived at the 22-kilometer diameter hole in the ground that the robot first drove onto ancient Noachian terrain. It was late August 2012 and the MER team had a "weak but real" signal for clay minerals in data collected by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), a visible-infrared spectrometer onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Arvidson, who is also a co-investigator on CRISM, had acquired additional observations and meticulously pinpointed the "sweet spot" to a hill that was named for Jake Matijevic, one of the original "creators" of Spirit and Opportunity and MAR rover pioneer at JPL, who had just passed away. It was a no-brainer and, since Opportunity was traveling south along Cape York, the timing was perfect. "We made a hard right and went to Matijevic Hill," said Squyres.

There, on Matijevic Hill, for the first time in all her years on Mars, the robot field geologist found clear, undeniable evidence for past near-neutral water, water humans could drink. It was in the form of phyllosilicates, specifically smectite clay minerals, exactly what it had come to ground-truth, exactly what CRISM indicated would be there. It put the MER scientists over the Martian moons, so to speak, and the mission made space exploration history as the first surface mission to uncover phyllosilicates and the first to travel geologically that far back in Martian time.

The same CRISM data is guiding MER to Marathon Valley, the next main attraction to the south. Only in this part of Endeavour's western rim, dubbed Cape Tribulation, the signals from the orbiting spectrometer are multiple and strong, indicating a bounty of different kinds of clay minerals. More than that, aerial imagery of Marathon Valley reveals a more defined stratigraphy in places, stratigraphy that no doubt harbors evidence of Mars' ancient history.

Although the skies are getting hazier with the springtime winds and Opportunity's power production is beginning its seasonal drop, the rover has plenty of power and all the mettle necessary to set out on the "long haul," as Arvidson described it, to the next science waypoint, a crest in Cape Tribulation. "The rover will be ready to continue the journey south whenever the scientists are ready," said Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering at JPL. "The events with Flash this past month are annoying and concerning, but they are not causing any significant impact to operations and the rover is doing very, very well."

The mission is ahead of its Marathon Valley schedule, no one is in a rush, and the rover is, for now, hanging close to the rim of Ulysses Crater. The MER scientists want the rover to check out the intriguing collection of rock types hurled out from beneath by whatever created Ulysses Crater. "I think we're going to be here for a while," said Squyres. Both Opportunity and her team have mysteries to solve.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Wdowiak Panorama

"When we saw this vantage point, we all went: 'Oh yeah, this is the place,'" said MER PI Steve Squyres. So Opportunity stopped in mid-September 2014 and took the images that compose the Wdowiak Panorama, shown above. "It's a beautiful view of Wdowiak Ridge from the south looking north, and beyond that you can see the Meridiani Plains, Murray Ridge, and into Endeavour," said MER Deputy PI Ray Arvidson. Although the official Pancam version has not yet been released, Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, planetary author, and member of UMSF.com, "stitched" the panels together and processed them in his Martian Technicolor version, which we present here.When September dawned at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was parked on the eastern flank of Wdowiak Ridge, 40.69 kilometers (25.28 miles) on her odometer, under master sequence control, and preparing for the reformat of her Flash drive.

The robot's bouts of amnesia – an inability to write to Flash before shutting down to go to sleep – and sudden, unintentional reboots, also called warm resets, had gotten so bad in August that the team couldn't get any work done. "We had a dysfunctional rover for almost two weeks," said Golombek. "There were so many resets that we couldn't do anything but deal with that."

Flash is a form of non-volatile memory that retains its contents even when the rover shuts down to go to sleep. Opportunity could, technically, continue operating without this memory and the team proved to themselves they could at the end of last month. On Sols 3767 and 3768 (August 29 and 30, 2014), engineers sent special commands to put the rover into a mode that does not use the Flash file system, what they call "crippled mode," during which the rover deliberately creates a RAM (Random Access Memory) drive instead of turning to Flash.

"Since it's during the day, we can stay awake through the afternoon UHF pass so RAM stays powered and the data files created in it can be sent," explained Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering at JPL. "Our efforts proved we could operate that way if necessary."

They don't want to have to though. Since RAM is volatile memory, which would disappear when the rover shuts down every night for DeepSleep, that system would "force the team to only take as much data as the rover can downlink in a single sol," said Nelson. "With Flash, we can take a panorama of 100 megabits or more and drive away while downlinking the data over the next several Sols. With RAM, we'd have to wait until it's done and downlinked before driving again. We could still do our science, but the pace of operations would be slower," he explained.

CRISM detections at Endeavour

This geological map is based on observations by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) which is searching for signs of water from onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Endeavour Crater is about 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter. This map covers a small portion of the crater's western rim. A discontinuous ridge runs north-south, exposing basalt (blue) and clay minerals (green) believed to be from a time in Martian history known as the Noachian Period, some 3.7 to 4.2 bilion years ago.NASA / JPL-Caltech / JHUAPL

Still, it's good to know and better to have confirmed it. The planned reformat preparations continued. On Sols 3769-3771 (August 31, September 1-2, 2014), Opportunity took a Tau, its daily measurement of atmospheric opacity, and then focused on downlinking data stored in her Flash drive. "We had to get everything down because the upcoming reformat would erase the entire Flash memory," said Nelson. "Obviously, if the objective was to empty Flash, it wouldn't be helpful for the rover to work and take a lot of data and fill that memory back up."

Opportunity remained under master sequence control for all three sols without any Flash-induced resets. Then, on Sol 3772 (September 3, 2014), the MER engineers began the process of copying a subset of necessary files from her Flash file system over to EEPROM (other non-volatile storage) for safekeeping during the reformat process.

The next sol, 3773 (September 4, 2014), the rover and her team began the actual reformatting process of her Flash file system. "The reformatting went well and the vehicle has been operating nominally," announced John Callas, during a recent interview with the MER Update.

During the reformatting process, an algorithm, ostensibly, tested the cells within each of the 8 banks of Opportunity's flash drive. If cells tested bad, then they were flagged and removed from the file system. That, of course reduced the amount of space available on the drive.

The good news was the space was only slightly smaller than before the reformat. Interestingly or perhaps ominously, it's exactly the same amount of space that was left after Spirit's Flash memory was reformatted. "The original size of the Flash memory available was 227,985,408 bytes," said Nelson. "After we reformatted Flash, that size was reduced to 226,257,408 bytes, a change of 1,728,000 bytes or 0.758%."

The MER team spent the rest of the first week of September finishing the process. On Sol 3775 (September 6, 2014), some scripts and configuration files were copied back to Flash from EEPROM, and other configuration files were loaded from the ground on Sol 3776 (September 7, 2014). At that point, the reformatting process was complete and Opportunity was given the green light to move on.

The winds of spring continued kicking up dust, but it was playing out like Martian Spring Light at Endeavour. While Tau continued fluctuating around 0.852, about the same as one month before, the fallout of dust onto the rover's solar panels, known as the dust factor, was holding around 0.771 and Opportunity was producing 713 watt-hours, plenty of power for roving on.

The plan for September was for Opportunity to drive up Wdowiak Ridge, named in honor of MER science team member and colleague Tom Wdowiak, to capture the traditional namesake panorama. From there, she would rove over to the relatively fresh crater carved into the southern end of the distinctive ridge, Ulysses, and "see what we see," as Squyres put it.

It had taken some time for Wdowiak Ridge to be christened. The team wanted his namesake to be something "really beautiful and memorable and befitting of the feelings we all had for Tom," said Squyres.

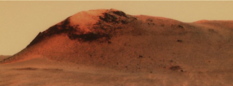

Wdowiak Ridge

The MER team wanted colleague Tom Wdowiak's namesake to be something "really beautiful and memorable and befitting of the feelings we all had for Tom," said MER P.I. Steve Squyres. "We saw this ridge from way off and I had a feeling, sort of identified this one in my head as a good candidate place. We chose well actually." Stuart Atkinson, MER poet and author of all things celestial, processed and colorized this version of the rover's image. For more of Atkinson's musings about and images from Opportunity's trek to and around Endeavour, visit his "The Road to Endeavour" blog.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Wdowiak, who passed away on April 27, 2013, was a beloved member of the original Athena Science team, and a payload uplink lead and payload downlink lead of the Mössbauer spectrometers for the MER Science Operations Working Group (SOWG) meetings, as well as a mentor to many and a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "We saw this ridge from way off and I had a feeling, sort of identified this one in my head as a good candidate place," said Squyres. "We chose well."

Actually, Opportunity first tried to take the Wdowiak Pan from the northern side back in August just as she was on approach to the geological feature, but the repeated resets made that impossible, so the MER team decided then to continue driving. The rover wound up on the eastern flank of the ridge, where she hunkered down for the reformatting process. Finally, as the second week of September got underway, the robot field geologist set out from that spot to fulfill her panoramic assignment. "We began driving up hill on Wdowiak Ridge to get in position to shoot to the north and capture the panorama in color," said Arvidson.

The ridge is covered with rocks and so Opportunity took off slowly on Sol 3778 (September 9, 2014), employing her Visual Odometry (VO) software to navigate around rock obstacles. The drive stopped almost as soon as it started though, because the VO software couldn't find enough visual features for the algorithm to converge.

Rover planners re-sequenced the drive, instructing their charge to use a different scene with more visual features. And, on Sol 3780 (September 11, 2014), the rover put 10 meters (a little more than 33 feet) of the rocky terrain in her rear view mirror.

The next evening, Sol 3781 (September 12, 2014), the robot took an atmospheric argon measurement with her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) for the mission-long study of the Martian atmosphere, and then got a good night's rest. The next sol, 3782, she trudged some 20 meters (more than 66 feet) through in the difficult terrain.

Although the driving had gotten tougher, Opportunity had been performing without any anomalies or unusual behavior since the reformat. But that was about to change.

Just a couple of nights before, on September 11th, the rover's Sol 3780, the MER engineers got an event record known as an EVR, from the Flash drive. "It basically said that Bank 7 wasn't ready," said Nelson. "That was followed by a power cycling of the Flash, which seemed to fix whatever the problem was, and there were no other apparent issue. But that kind of put us on notice. It was out first indication that there is still something wrong with the Flash memory."

Sure enough, just four sols later, on Sol 3783 (September 15, 2014), the rover was unable to mount her Flash file storage system during the wake-up for DeepSleep, and suffered an amnesia event. "It was like all the others we'd seen in the late evening wake-up to go into DeepSleep, and that was discouraging," said Nelson. The rover hadn't been working so no science data was lost as a result and the robot herself was otherwise in good health.

Previously, when Opportunity experienced Flash issues, there were almost all traced to Bank 7 among the Flash drive's 8 banks. So the team's software engineers went to work, trying to investigate and determine what to do next.

Up on Mars, Opportunity took off undaunted on Sol 3784 (September 16, 2014), as if nothing happened and put another 30-meters (98 feet) on her rocker bogie, driving just northeast of Ulysses Crater. The rover followed a high crest that runs north-south on the ridge and then transitions into a saddle. There, in the saddle, the robot field geologist stopped. Her team took a look around and knew, sometimes, things are just meant to be.

"When we saw this vantage point, we all went: 'Oh yeah, this is the place,'" said Squyres.

So from this location, Opportunity spent Sol 3786 (September 17, 2014) focusing on the world around her and taking the images that would be merged together into the Wdowiak Panorama. "It's a beautiful view of Wdowiak Ridge from the south looking north, and beyond," said Arvidson. "You can see the Meridiani Plains, Murray Ridge, and into Endeavour."

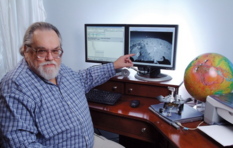

Tom Wdowiak

MER science team member Tom Wdowiak, a longtime professor astronomy and astrophysics of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and mentor to many in planetary science, is pictured here in his home office. Tom was a member of the original Athena Science team and a payload uplink lead and payload downlink lead of the Mössbauer spectrometers for the MER Science Operations Working Group (SOWG) meetings. Even after retiring to professor emeritus, Wdowiak continued on MER from his this office and worked nearly up to the point of his unexpected passing on April 27, 2013. "He is deeply missed," said MER PI Steve Squyres.Mössbauer Effect Data Center

By most accounts, it is probably a view more spectacular than it would have been had the rover been able to complete the assignment last month. That pan would have had more pixels across the ridge itself, Squyres said, but in the background there would have had just been sky. "From the vantage point we chose, we still get a beautiful view of [part of] the ridge, but in the background, you have the entire sweep of Endeavour Crater."

Opportunity was at a slightly higher elevation "about 10 meters," said Arvidson, and it made all the difference. "It's just a phenomenally great view."

"I'm really, really happy with the way this one's come out," agreed Squyres. "It's a real beauty."

Later that same sol (different day on Earth, September 18, 2014), Opportunity suffered her second amnesia event since the reformat, again during the wake-up for DeepSleep. Again, it didn't stop this rover. The next morning she got up and drove 13.5 meters (a little over 44 feet), relying again on her VO software to safely navigate her way through the rocky field across Wdowiak Ridge. The rover was heading to the southern end of the ridge, to Ulysses, the small young crater named for the spacecraft that studied the Sun.

"Using visual odometry means our drive rate is lower than without visual odometry, because the rover has to take the time to take images and do the processing," said Callas. "But because of the abundance of rocks in the area around Ulysses Crater, we want to take it slow and steady."

The idea was to have Opportunity drive as close to the Ulysses' rim as she could get, peek inside, and do some IDD work. "So imagine, we are now north-to-northeast of Ulysses Crater, a young crater with a lot of ejecta blocks, and trying to figure out the best approach with the minimum number of rocks," said Arvidson. "We wound up driving along the eastern flank of the ridge, downhill of Ulysses Crater, to climb up from the southern side, where there is a little cut or opening in the rim."

On Sol 3789 (September 20, 2014), Opportunity cautiously maneuvered closer to the rim of Ulysses, but the drive stopped after 15 feet (4.6 meters) because her VO was not tracking on the last steps. The rover suffered a third amnesia event later that night local time. "All three of these amnesia events occurred at the same time they usually had, in the wake-up for DeepSleep," said Nelson. "Now they may be symptoms of something more serious, but in and of themselves, these events didn't really cause us problems."

Down on Earth, MER ops engineers continued to investigate the Flash-related issues.

"We've seen these events before, but we still don't know for sure what this is," said Callas. "We have theories that it's just Flash cells wearing out. But we have no idea about why they have a preference for waking up to go into DeepSleep. There's nothing particularly unusual about that time that we can tell. It's not the hottest or coldest temperature, so it's not connected to a thermal effect that we can see readily. The rover is relatively quiescent, writing data products to Flash, but it's doing that whenever it's awake, so we don't know why it's that time. We are fortunate that it's a benign time of day. If this were to happen during the day, then it becomes more problematic." More was to come.

The robot field geologist took another routine APXS measurement of atmospheric argon on Sol 3790 (September 21, 2014), then woke up the next sol, 3791, to take a short 4-meter (13-foot) jaunt, edging closer to Ulysses. "It's very sandy there, but we drove up as high as possible and could see the crater's western wall," said Arvidson.

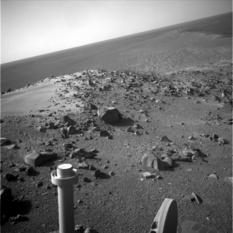

Partial peek into Ulysses

Opportunity took a series of images with her Navigation Camera that were still in the processing of being downlinked at the time of the MER Update September 2014 posting. But this is one of the raw images the rover took near the end of September. It offers a partial peek or the peek into Ulysses Crater from a point on the rim where the rover dared to rove, high enough up, it looks, to be something of a shuddering view for a little rover.NASA / JPL-Caltech

Although high slip prevented the rover from completing the turn for communication at the end of the drive, Opportunity was close to the edge when she took the images needed for the panoramic view of Ulysses' interior. "We didn't quite get all the way to the edge, but we got far enough in that we could see the far rim, and a little of the interior," said Golombek.

During the Sol 3791 late night wake-up to start DeepSleep, Opportunity suffered another memory-related issue known in the jargon as a Flash 'write block not complete' error that was followed by a Flash power cycling, "an event very similar to the events that caused warm reboots in the past," said Nelson. "This was the first such event after the reformat, and it was followed the next morning, Sol 3792 for Opportunity (September 23, 2014) by a second Flash 'block write not complete' error and another power cycling during the solar array wake-up."

Both issues were traced to the Flash drive's Bank 7, "the same suspect bank," noted Callas.

Meanwhile, Opportunity was really revved up. "It's not healthy for the battery to be kept at or near full charge for long periods of time," said Nelson. So, on Sol 3793 (September 25, 2014), the team decided to delay starting DeepSleep so the rover could burn some battery energy. Everything was fine until the rover was to start DeepSleep. Again, she suffered an amnesia event followed by the first warm reset or unexpected computer reboot since the reformat.

"Since we did no late evening observations, nothing of consequence was lost to the combination amnesia event and warm reset," said Nelson. "And nothing that happened this past month set us back really or put the rover at any risk whatsoever."

None of the events in September actually led to any loss of scientific data. "These events have been annoying and they are an indicator that there is still some issue with Flash," Callas admitted. "But they don't represent a health and safety issue," he reiterated.

For Squyres, there was "no surprise" here. "When you reformat Flash, you can clear up some of the problems you're having but you're not necessarily going to get them all," he said. "We still have some bad locations in Flash. It does slow us down a little bit, but the situation [in September] is dramatically improved from what it was before the reformatting. Right now, we have several approaches and are currently assessing what we're going to do moving forward."

The 'rub' that always comes with reformatting is that some cells in a given sector of a given drive might be intermittent – "somewhere in between good and bad," as Callas put it – and could pass through reformatting only to present problems downstream. That's one hypothesis of what's happening now.

If the problem is one of intermittently bad cells – and since the issues were not corrected in the recent reformat that is a reasonable explanation – theoretically another reformat would likely help and could solve the problem. Therefore, when and if circumstances dictate, another reformatting of Flash is obvious possibility. It could be Bank 7 is going bad and if that's the case another possibility is to mask off that bank, leaving banks 1-6 for data. [Bank 0 is used for flight software.]

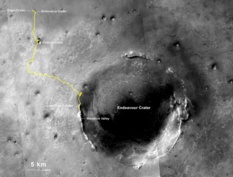

Opportunity's yellow brick road

The gold line – or Yellow Brick Road for those with imaginations – scrawled on this image shows Opportunity's route from her landing site inside Eagle Crater, upper left, to the rover's approximate location on Endeavour Crater's western rim. The base image for the map is a mosaic taken by the Context Camera, onboard MRO. The rover is en route to Marathon Valley, but is stopping along the way to smell the roses, which translates to check out weird rocks and stuff. The veteran MER set the new off Earth distance recordfor a robot on another planet in July 2014 and is still going strong.NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

"But Opportunity's Flash issue could be caused by something else," said Nelson. "We've always been concerned that there might be areas of memory that remain bad but are intermittent, but there could also be a bad spot in memory that we just don't access very often," he pointed out. "That would mimic an intermittent. Or it could be a timing issue, where things are degrading and not operating as fast as they used to, or it could be some other kind of memory issue," he said.

In Flash memory, Nelson explained, you inject a charge into what's called a buried gate, basically it's like a capacitor, and that charge can leak off. Generally, you need to refresh it every 10, 12 years. "But if you erase and rewrite, your erase won't take all the charge back out, and eventually a time comes when a certain amount of charge just sticks there," said Nelson. "Then you find yourself midway between a 1 and a 0 and the cell is no longer working properly. That is when a cell is said to be worn out. This may be what's happening."

Since the reformat reduced Oppy's Flash memory by exactly the amount it reduced on Spirit, that is now making the MER software engineers consider the possibility that maybe there is some structure in this Flash memory that is not subject to load leveling, "probably something that defines the overall structure of the Flash memory," Nelson said. "This structure has to be in a fixed location in order for the flight software to find it. Presumably, it contains pointers to where stuff was moved around in Flash from there, but the hypothesis, in this scenario, is that this fixed structure in the memory wore out on both Spirit and Opportunity. When we reformatted, that structure was placed elsewhere and the old structure was then removed from Flash."

One difference between Spirit's reformat and Opportunity's is that Spirit's Flash was effectively "cured," and that rover had no subsequent problems. "But Spirit died at age 7," Nelson reminded. "Opportunity is now age 10 and has done significantly more writing to Flash."

So, as Opportunity roves on, the MER engineers at JPL will continue their investigation of Opportunity's Flash issues. "We just don't have a lot of information from the spacecraft that would help us figure out what's going wrong, so it's taking a while to come up with hypotheses and ways of testing or just getting more information," said Nelson.

The team however does have an immediate plan for moving forward: instrumenting the amnesia events. "When an amnesia event happens, it stores all its information in a RAM disc," said Nelson. "We're going to take all the EVRs that are stored and move them to EEPROM. Then when we get the Flash data back, we will be able to see the EVRs from the amnesia event. We're hoping that maybe this data will give us a better clue as to exactly what's happening."

That plan is in the works now. "We have to figure out exactly what we're going to do and then run it though the test bed before we can uplink it and try it on the spacecraft," Nelson said. "And then we have to wait for an amnesia event."

In the meantime, Opportunity seems oblivious to the problem and is, as the team officials all say, "in otherwise good health." Summed up Golombek: "We have been able to do everything we wanted to do and we have been operating unfettered."

Field of Martian dreams

Whatever impacted the Martian surface at the northern end of Wdowiak Ridge and carved out the crater called Ulysses hurled up a lot of rocks that are spread all around in an obvious ejecta field. Using special Visual Odometry software Opportunity carefully maneuvered through the rocks in September 2014. By month's end, the robot had presented the MER scientists with a diversity dilemma and something of Martian mystery or, in MER PI Steve Squyres' words, rocks that are "a little different than things we've seen." They were interesting enough to hang around for a while and so, from this field of rocks, the robot field geologist bid adieu to September and welcomed October 2014.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

During the final weekend of September, the rover bumped to position herself in front of Hoover, a dark grey rock apparently hurled up from beneath when Ulysses Crater was formed. It is one among a bounty of ejecta that has the scientists intrigued and somewhat puzzled. "We haven't had many rocks we've measured at Meridiani Planum that aren't Burns Formation," said Golombek, "and so this dark grey, hard, strong rock that is broken up into these big chunks is really cool, and it will be very interesting to see what this is."

As September faded to history, Opportunity was in the process of making a short 2 to 2.5 meter hop to another nearby Ulysses rock, dubbed Lipscomb, to continue her work in the ejecta field. "The reason we went to Ulysses is that, being a decent size crater, it will have excavated through the surface materials and down into the stuff underneath," said Squyres. "What we're finding is that there may be two or three totally different rock types in the ejecta field of this crater."

While certainly part of the Endeavour rim, Ulysses' ejecta field is looking in some respects "a little different than things we've seen," Squyres mused. "This was a hard place to get to. We had to fight our way up hill. It looks like it's paid off in terms of providing us with some real interesting rocks with significant diversity and interesting scientific targets with multiple lithologies. We want to make sure we sample the diversity and do our best to understand it before we move on," he said. "We're going to take our time here."

It's been recorded before, many times in these pages, and it has always been true: the future for Opportunity looks bright and the rover's prospects for returning textbook-changing science remain great. As the veteran MER continues her journey further back in Martian time, the lucky star that has been shining on this mission from the very beginning seems almost to promise the Martian mysteries and surprises will continue.

Although Opportunity lost the use of both her mineral detectors in the past few years, it hasn't stopped the mission's ability to uncover the science. "The key thing is that with years of experience under our belts we have learned ways to use elemental chemistry to infer things about the mineralogy," said Squyres. "For example, some of the results that we achieved on Esperance [on Matijevic Hill] really point very strongly towards an aluminum rich clay. That's a conclusion derived entirely on the basis of elemental chemistry data."

A single APXS measurement by itself tells the scientists about the elemental chemistry in that field of view, but when Opportunity takes many APXS measurements, overlapping measurements, and uses her full scientific capability, documenting those targets carefully with imaging, it turns out the MER scientists can infer quite a bit about the mineralogy. "That's part of the strength of the payload we still have," said Squyres.

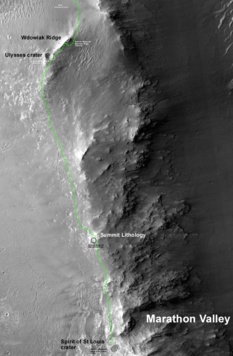

The road ahead

Opportunity's past and planned route south to Cape Tribulation and Marathon Valley is charted here in green. As October 2014 began, the rover was still working at Wdowiak Ridge/Ulysses Crater, where it has found an intriguing diversity of rocks. Once that research is done, she will begin the "long haul," as MER Deputy PI Ray Arvidson calls it, to the next waypoint on the journey to Marathon Valley.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / NMMNHS

Although the weather has been mild for Martian spring, Opportunity's power production dropped about 70 watt-hours to 639 watt-hours. It's not outside the realm of expectation given the season, but the season has only just set in and it is a clear reminder that Mars is always ultimately in control.

"We are mindful of the fact that dust storm season looms ahead of us," said Squyres. "We've been through Martian spring many times before, but you don't know what you're going to have in the way of dust storms, so basically you just push the rover as hard as you can, whenever you can. That's what we're doing. As we've always been, we're at the mercy of the Martian weather."

The plan for Opportunity to get to Marathon Valley with six or more months buffer to explore before the next Martian winter begins on Endeavour still holds. With the next Martian winter expected to blow in sometime in late October 2015, the robot field geologist right now is well ahead of schedule, and roving just fine. "We're in good shape," summed up Callas. "Other than the Flash-related anomalies, it's been smooth."

With its mission extension secured, the MER team is looking forward as optimistically as ever. "Marathon Valley is right out there ahead of us and it's just calling out to us," said Squyres. "Ever since we first saw the CRISM data, we've been calling it the mother lode. We've demonstrated with the payload we've got that we can do good science in this kind of terrain. We have very high hopes."

In other MER news: The "Spirit and Opportunity: 10 Years Roving Across Mars" exhibit at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum in Washington DC closed September 14th. But the panels of images the twin robot field geologists sent home to Earth will continue to be displayed in various different places around the Institution, said John Grant, MER science team member and supervisory geologist in the museum’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies.

Although the exact locations are to be determined based on space available, some panels, all of which are now owned by the Smithsonian, are expected to be in the Education area in the Mall building. For now though, as the crews are busy preparing the gallery for the next exhibits, the panels of Martian images taken by Spirit and Opportunity are being temporarily stored.

The life-size model of the MERs however has roved over to the Milestones of Flight galley and parked next to the model of Curiosity. At some future point, the MER model, which was made by students at Cornell and loaned to the Smithsonian, will rove back to the Exploring the Planets gallery where it was before the rovers got their own temporary exhibit. So rest assured, while the exhibit may be closed, Spirit and Opportunity have not left the building. Not yet. Maybe not ever.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth