A.J.S. Rayl • Oct 04, 2016

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Exits Marathon Valley then Rocks Spirit Mound

Sols 4482 - 4510

It was another September to remember for the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission as Opportunity cruised through the Lewis and Clark Gap and out of Marathon Valley, then hiked downslope, leading the first overland expedition of the Red Planet to Spirit Mound, a new site deep in Endeavour Crater’s rim.

“We have completed the ninth mission extension and are now starting the tenth,” said John Callas, MER project manager, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), home to all of NASA’s Mars rovers. “We are in a new phase of the mission.”

The MER team’s extended mission plan was written, presented, reviewed, and approved earlier this year. In July, MER was granted another two-year mission extension, which, in essence, allocates the funds to keep Opportunity roving through 2017 and 2018.

After more than a year of roving around Marathon Valley, an area roughly the size of three football fields, however, the views had gotten old. Having completed research on the remnants of ancient clay minerals the mission came here to ground-truth, and characterizing zones in the valley where water trickled or flowed millions to billions of years ago, neither Opportunity nor her Earth-based colleagues had any good reason to hang around.

So, on September 4th, months ahead of schedule, the veteran robot field geologist left Marathon Valley, heading east and downhill toward the interior of Endeavour Crater.

“Once we shot through that gap and started heading down the hill and were just motoring along, it was a good feeling,” said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University. “It's actually really fun to be on the road again.”

The MER team, with the aid of orbital images taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), charted a route for the veteran robot to follow for the next two years. The route and accompanying plan is what garnered them their extension. Even so, a plan is a plan.

The HiRISE images are taken several hundred miles to thousands of miles above Mars’ surface, so until the rover is on the road and the rover planners can see the terrain and the landscape in the ground images the robot sends home, there are no assurances that every part of the planned route will offer safe passage.

Opportunity has always had something of the “luck of the Irish” though and as she drove through the gap and began the hike downhill, the road ahead looked good, inviting even, a little rocky in places, but clearly passable. “We made a beeline for Spirit Mound, the first waypoint on the extended mission,” said Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL).

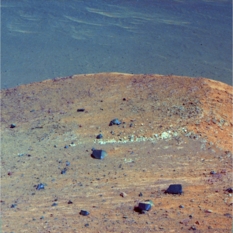

Spirit Mound

Opportunity took this image of the western side of Spirit Mound on Sep. 21, 2016 with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam). It is named after the landmark prairie park in South Dakota that Lewis and Clark visited in the early 1800s, with a sentimental nod to the Opportunity’s twin. The image was processed in false color by the Pancam team, a technique that enables scientists to better discern different features. The light-toned linear outcrop in the center of the image became the subject of study at the end of September.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Driving downhill on somewhat challenging, 15-degree slopes peppered with rocks and cobbles could have been perilous. It’s probably not for the robot faint of heart. But Opportunity and her drivers, the most experienced in the world, made it look easy. By month’s end, the rover had put Marathon Valley in the rear view mirror and 258.55 meters (848.26 feet) on her odometer.

“The driving has been fantastic,” said Mike Seibert, MER’s lead flight director and rover planner at JPL. Although Opportunity did slip a bit as she went – “actually skidded downhill a little,” Seibert said – the rover had no real issues getting to Spirit Mound.

“Opportunity loves the downhill run,” Squyres said.

“This rover has always amazed us. We're driving on tough terrains, and she is handling it very well,” elaborated Ashley Stroupe, a rover planner at JPL. “And at this point, we're not seeing any new troubles cropping up.”

As the rover trekked toward Spirit Mound, the MER scientists on Earth were on the lookout. This particular segment of the extended mission had been charted not just because it would take the mission to this oddly familiar mound, but also because it would take them downhill into the crater rim through various bedrock layers or strata and, in effect, back in Martian geological time.

They set out hoping the rover would uncover more of the ancient Martian ground it first found on Matijevic Hill back in 2012-‘13 at Cape York. Known as Matijevic Formation, this bedrock represents what was the surface of Mars at the time Endeavour Crater was created, the Noachian Period some 3.7 to 4 billion years ago when Mars was more like Earth, with lakes and rivers, even, perhaps, an ocean.

That discovery drove the MER mission back into the news headlines. Since Opportunity is the only surface mission investigating this timescape, finding more of it is highly desirable for obvious reasons. The team hypothesized the rover might find more of the ancient bedrock in Marathon Valley, but that didn’t happen. The hope in September was that she would find the ancient bedrock en route to or around Spirit Mound. “All we can do is see if it's there,” said Matt Golombek, MER project scientist, of JPL. “The only way to know is to go.”

While Opportunity was descending into the rim toward the mound, the MER ops team also kept close watch on two regional squalls that were whipping up the powdery Martian dust and darkening the atmosphere. “We were tracking those two dust storms pretty well,” said Seibert. “If they had strengthened rather than dissipated, we could have been in a world of hurt, but no major dust storms showed up to cause us problems.”

From Marathon Valley, the robot ultimately hiked down nearly 60 meters (about 195 feet) in elevation before reaching Spirit Mound. At the base of the mound, the robot was close, presumably, to the same elevation as Matijevic Hill. But the scientists have not seen any Matijevic rocks.

Of course, there is no way of knowing just how the rocky rim of Endeavour was jumbled up and sorted during the impact that created the 22-kilometer (13.67 miles) hole in the ground, not at this point anyway.

“We haven't found anything akin yet to Matijevic Formation and we made it about as far down or east as we're probably going to go in Cape Tribulation,” confirmed Arvidson. “It looks to me like the rocks we're seeing, including Spirit Mound, are more of the impact breccia, Shoemaker Formation breccia that we saw in Marathon Valley,” he added, rocks formed from angular rock debris produced by the asteroid or comet or whatever caused the impact created Endeavour some 4 billion years ago.

Opportunity’s findings at Spirit Mound seem to have convinced at least some of the MER scientists that Cape Tribulation is all Shoemaker Formation and that the Matijevic Formation, which lies underneath the Shoemaker bedrock and represents the pre-impact surface of Mars, will probably not be found near Spirit Mound.

Arvidson honored

The MER mission serves as a training ground for young scientists and engineers, and the team, as well as various individuals working on the mission, have won all kinds of awards over the years. While Opportunity continues to rove, the education and the honors continue too. In September, the Society of Applied Spectroscopy honored MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL), with the Lester W. Strock Awardfor his research on Mars. Top row, left to right: Scott Murchie, principal investigator of the CRISM spectrometer onboard MRO, of Johns Hopkins; Arvidson; Abby Fraeman, a Planetary Society student astronaut on MER in 2004 and now MER deputy project scientist of Caltech-JPL; and Bethany Ehlman, assistant professor at Caltech, who also worked on MER as a student. Arvidson mentored both Ehlman and Fraeman. Bottom row: Eloise Arvidson; Diana Blaney, of Caltech-JPL, a former MER deputy project scientist, now the P.I. of the MISE spectrometer on the Europa mission; and Richard V. Morris, a MER science team member from NASA/JSC.SciX / Society of Applied Spectroscopy

They’re “not giving up” though, Arvidson said, noting that there is still a chance for uncovering more of the ancient Martian ground later in the extended mission.

In the moment, Spirit Mound is something new on Mars for the rover and the mission. As the rover’s luck would have it, this Martian mound has a strange light-toned, linear outcrop running through it and that is making this geological feature even more interesting up close than it was from a distance. “We're working on it,” said Squyres.

As September falls to October, Opportunity is parked right up against the western edge of Spirit Mound, hunkered down over a bedrock target on that linear outcrop called Gasconade, checking it out and documenting it with images.

The skies overhead are still really hazy as dust storms whip up and then dissipate in various areas of the planet. Because of all the dust kicked high into the atmosphere, the solar-powered rover felt the impact this past month in terms of energy production, as she did in August. Fortunately, the storms continued to whirl at safe enough distances from Endeavour throughout September and the rover produced plenty of power to keep on schedule.

The plan forward calls for Opportunity to keep on roving, visiting and studying a host of exciting geological attractions that have been mapped out. “As soon as we're finished with Gasconade, we'll head to the southwest, kind of caddy corner from Gasconade, and drive back uphill on Cape Tribulation,” said Arvidson.

“We are not going to retrace our tracks,” Squyres said. “We're going to sort of angle across. Going uphill is harder than going downhill, but we're very confident that we can make our way back up.”

Back at the top of that Cape Tribulation hill, Opportunity will check out several targets the scientists have spotted. “I suspect they are all breccias, but we'll do a kind of taste of them,” said Arvidson.

The longer-term objective is to head south across the plains or along the apron on the western side Endeavour’s west rim and over to Cape Byron where there’s a gully believed to have been carved by water or a liquid debris flow. The gully, actually, is the centerpiece of the extended mission and the scientists are bent on exploring it from the top to the bottom.

The MER scientists have always strived to be thorough in their scientific investigations, but the gully is a big deal. The rover’s work there will mark the first time a surface mission on Mars has investigated a liquid-carved gully up close and whatever they find, it will reveal something more about past water on the Red Planet. After that, the rover probably will enter Endeavour from the bottom of the gully where more Martian secrets are likely to be uncovered...but that’s down the road a ways.

Opportunity seems to be ready for all of it. “We've got good power and things are wonderful,” reported Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering at JPL. “Some of this terrain will be quite challenging to us, but we believe the paths we've chosen are within the technical capability of the rover and we're optimistic that we won't have to make too many adjustments.”

With an ever-willing robot, new views and navigable landscapes ahead, and knowing discoveries lie ahead, the MER ops team – 12 years, 8 months and counting into what was originally to be a 3-month tour – seems to have gotten its ‘tenth wind.’

“I think getting on the road again has kind of energized the whole team,” said Squyres. “It certainly has energized me.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Gasconade

As Opportunity pulled up to Spirit Mound, the MER scientists couldn’t help but notice this intriguing, light-toned linear outcrop. After naming it Gasconade, for the river where the Lewis and Clark Expedition set up camp in 1804, the team directed the rover to check it out as best she could. “It's small and very rough,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell. “We'll do what we can with this thing and then it will be time to move on.” [Unless, of course, Opportunity finds anything rover-stopping compelling.When Opportunity woke up on Sol 4482 (September 1, 2016), ready to drive into the new month, it was around +32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 Centigrade) outside, downright balmy for Mars. The rover hit the road, driving 24.08 meters (79.00 feet), the final leg across Marathon Valley up to the Lewis and Clark Gap.

The robot field geologist spent the next couple of sols drinking in the views and taking dozens of pictures of all that she could see to document this part of the expedition, this time and place. Once she roved through the gap, Marathon Valley would be a chapter in the past.

From her position at the gap, Opportunity took pictures of the valley just south of Marathon Valley with her Navigation Camera (Navcam). Dubbed Bitterroot Valley, it was where the rover’s new adventure and extended mission would begin. “We wanted to make sure it was safe,” said Arvidson.

The robot also focused her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) on a distinctive rocky ridge to the east, on the other side of the Lewis and Clark Gap from Knudsen Ridge. Then, on Sol 4485 (September 4, 2016), Opportunity took off. Driving through the gap and into Bitterroot Valley, the rover put 23.58 meters (77.36 feet) behind her and set out on a trek farther down into Endeavour Crater’s rim and onto her next truly excellent adventure.

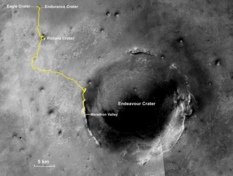

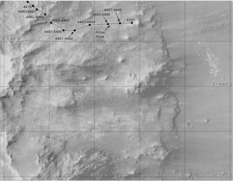

Oppy’s expedition so far

The gold line on this image shows Opportunity's route from the Eagle Crater landing site to her approximate current location. Since August 2011, the MER mission has been exploring the western rim of Endeavour Crater and in July the rover entered Marathon Valley. The base image for the map is a mosaic of images taken by the Context Camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Larry Crumpler, of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, provided the route add-on.NASA /JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

“The sol we drove out of the boundary we drew at Marathon Valley was a big day,” said Stroupe, who got to plan the drive. “It felt very significant to me, getting to move on. Other than Spirit’s work around Home Plate, we have never investigated any place as thoroughly as we investigated Marathon Valley. We learned an awful lot, but it was definitely time to move on.”

Opportunity was starting all over again, again. With the new phase of the mission already charted and mapped out, the team didn’t waste a minute. The rover was commanded to head for the first waypoint some 225 meters (738.18 feet) or so down the road.

New phases and new sites have generally called for new naming themes on the MER mission. In Marathon Valley, the team christened targets after the members of the Corps of Discovery. Popularly known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, it was the first American expedition (May 1804-September 1806) to cross what is now the western portion of the United States.

Squyres asked for ideas. “The team is really into this whole Lewis and Clark thing, so the theme they liked was: places that the expedition visited and that's what we chose,” he said. “Then, as we went down slope and saw this hill in front of us, the first waypoint, I said: 'We need a name. What have you got?'”

Spirit Mound was on the list team members had been preparing. That was pretty interesting. Squyres went online and pulled up a picture.

Rising majestically from the prairie landscape about 6 miles north of Vermillion, South Dakota, Spirit Mound is a national historic site, a state park, and one of the few remaining geological landmarks on the upper Missouri River that is immediately identifiable today as a place Lewis and Clark explored.

“It probably looks different from different angles and obviously it's covered with grass, and there’s no grass on Mars,” said Squyres. “But from the picture I pulled up, it looks an awful lot like the mound on Mars.”

Of course the name struck a chord for another, obvious reason: Opportunity’s twin, Spirit. “Many of us thought it was appropriate that we name the first stop after something significant,” said Stroupe.

“The fact that the Spirit rover name appeared in the name of this site was one of the things that motivated us to pick it,” Squyres admitted. “We just had to do it.”

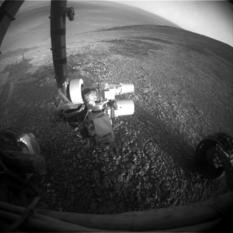

Roving out of Marathon

Opportunity took this raw image with her front Hazard Camera (Hazcam) on Sep. 2, 2016, just before she drove through the Lewis and Clark Gap [visible in upper left quadrant], left Marathon Valley forever. The trek to Spirit Mound was downslope almost all the way and the rover completed it even before the month had come to an end.NASA / JPL-Caltech

Meanwhile, despite the ‘muddy’ skies, the outlook for driving was bright enough. Opportunity didn’t experience any of the seasonal dust storm activity directly, although she did feel the impact of the elevated atmospheric opacity or Tau over Endeavour. It was reflected in the her lower daily energy production, which fluctuated around 475 watt-hours, or about half her capability on landing back in 2004 with clean solar arrays.

On Sol 4487 (September 6, 2016), Opportunity roved on, navigating 33.28 meters (109.18 feet) down the pebbled, sometimes rocky road and taking the usual post-drive Navcam images. As the first week of the month turned to the second, the robot focused on taking color Pancam images of her surroundings and chosen targets.

The rover continued the downhill trek to Spirit Mound on Sol 4491 (September 11, 2016), Driving due east, Opportunity put another 25.98 meters (about 85.24 feet) behind her, making steady progress towards the first attraction on this new phase of her mission.

Opportunity spent the next sol taking routine post-drive Navcam and Pancam images, and then drove again on Sol 4493 (September 13, 2016), logging another 37.54 meters (about 123.16 feet). That night, she also took an atmospheric argon measurement with the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) as part of the mission-long study on Mars’ atmosphere.

By the third week of September, the dust in the atmosphere had dissipated a bit, with the Tau improving to 0.889, down from 1.079 where it had been hovering at the end of August, a level of haze that automatically causes concern.

Though the background atmospheric opacity continued to be “elevated across much of the planet,” Opportunity continued to work and rove under “storm-free skies,” according to the MRO MARCI weather report. And the veteran robot began producing a little more energy, up around 520 watt-hours of power, and was still sporting a decent solar array dust factor of 0.698.

At this point on her trek to Spirit Mound, the rover engineers decided to have Opportunity try to back up the hill she had just come down, just to see if she could. On Sol 4495 (September 15, 2016) the robot backed up 3 meters (about 6 feet) “straight backwards,” said Seibert. “We measured around 10% slip during that backwards climb test, which is quite promising. That is to say, if we wanted to, we could probably scurry all the way back to Lewis and Clark Gap.”

But this mission was moving forward. Neither the rover nor the team member had any intention right now of backtracking. Still, it was good to know their field geologist was capable of it. Opportunity moved on, driving 48.35 meters (158.62 feet) that same sol, taking both Pancam and Navcam panoramas along the way to document the terrain and to provide drive-direction paths.

Oppy’s recent roves

This graphic charts Opportunity's recent rovings and science stops. The Lewis & Clark can be seen under the line connecting Sol 4484 to Sol 4485. The annotated map is courtesy Phil Stooke, associate professor, University of Western Ontario, Canada, and author of The International Atlas of Mars Exploration Vol. 2, Spirit to Curiosity: 2004 to 2014(Cambridge University Press, 2016). The base image was taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / P. Stooke

On Sol 4497 (September 17, 2016), the rover put another 27.71 meters (90.91 feet) in the rear view mirror and then spent a couple of sols shooting images and taking care of routine rover business.

The ops team worked with Opportunity on Sol 4500 (September 20, 2016) to update her actual position on the planet, a matter of course and necessity when roving on Mars and communicating with a crew on Earth, and together they successfully completed the procedure known as a Quick Fine Attitude (QFA). That same sol, the rover also put another 26.95 meters (about 88.42 feet) behind her and pulled up to the base of Spirit Mound.

“The drives were pretty much a straight shot, no slalom – we pretty much went straight downhill,” said Squyres. “I wouldn't say it was easy, but it was a fairly straightforward drive.”

Despite her ‘frozen’ or unsteerable right front wheel, an old injury caused by a jammed steering box, Opportunity had driven forward through the Lewis and Clark Gap and continued driving forward throughout the entire downhill run to Spirit Mound.

That’s interesting because turning on that injured wheel causes stress and the rover drivers know that driving with that front wheel weighted can be difficult, so Opportunity often drives backwards.

“Turning around does put some pretty good stress on that right front wheel, but we were already kind of pointed forward at the gap so we could image the ridge on the far side and Bitterroot Valley, and we just continued on,” said Seibert. “We were also getting a lot of help from gravity so that front wheel didn’t have to work as hard to get up to speed and keep the rover moving.”

Opportunity did experience slips, ranging from 10% to 20%, and the wheel currents at times spiked. “We've been driving over an area that has many small cobbles on it and as we drive sometimes the torque from our wheels causes these things to spin underneath us, so we've seen some variation in the attitude of the rover and we've seen some spikes in the drive current,” said Nelson. “But we believe that these things are fully explained by the terrain and, given that, it has not been a concern to us.”

The rover drivers are nothing but happy. “It's been better driving than we were expecting,” said Seibert. “The HiRISE imagery made this look to be more difficult driving than it's turned out to be. There was a darker albedo feature that we thought might be different terrain we'd have to work with, and there have been some rocks we've had to traverse over, and we had to zig-zag just a little to avoid larger ones. But once we could see Spirit Mound, we just headed straight there.”

The darker area turned out to be a shadow caused by the Sun’s angle at the time HiRISE camera took the image, Seibert said. “Occasionally, we get fooled by the shadows, but it's better to be safe and assume it's a rover-eating sand-trap or some other problem and go carefully into that region, rather than bomb across it with our eyes closed.”

This rover, you may remember, has been there and done that. Purgatory Dune, the sand ripple that caught Opportunity and the team by surprise back in 2005 when the rover was racing across the Meridiani plains was a lesson hard learned. It’s a memory that still looms large in the memories of those who were working the mission then.

There were no ripples in Bitterroot Valley though and now that Opportunity was at Spirit Mound, there was work to be done. “This had clearly been our key target for the first stop on the extended mission and is a place we definitely wanted to go,” said Squyres. “We didn't have a name for it when we wrote the extended mission proposal, but we knew this is where we wanted to go.” They didn’t know they would find a strange light-toned linear outcrop running across its western side.

Opportunity spent her Sol 4501 (September 21, 2016) taking Pancam and Navcam images of the mound, as well as of nearby boulders, and also worked in some camera time to look for dust devils.

The rover drove 7.73 meters (25.36 feet) on Sol 4502 (September 22, 2016) to a different position and took the usual images for a post-drive Pancam mosaic of Spirit Mound. As the science team considered possible surface targets on Spirit Mound, the robot devoted the next couple of sols to taking care of routine engineering business and taking more pictures of her surroundings. She snapped some color Pancam images of Spirit Mound, performed a Pancam low Sun survey, and took Microscopic Imager (MI) sky flats on Sol 4503 (September 23, 2016).

The following morning, the rover took a Pancam horizon survey and then shot a color Pancam image of the distinctive, light-toned linear outcrop on the western edge of Spirit Mound that the team had named Gasconade. The robot also shot another target called Council Bluffs, a rock target south of Gasconade, and also collected some Pancam images of mound’s ridgeline.

Spirit Mound on Earth

The grass on Earth’s Spirit Mound, located about 6 miles north of Vermillion, South Dakota, is definitely greener than on its namesake on Mars. “There’s no grass on Mars, of course,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres. But, he said, they look an ”awful lot” alike.Kevin O’Keefe

On Sol 4505 (September 25, 2016), Opportunity bumped again, this time for just 3.31 meters (about 10.86 feet) scooting up to Gasconade. The next sol she took a Navcam image of her tracks, a Pancam image of a breccia rock target named Portland, and a Pancam mosaic of the top of Spirit Mound above Gasconade.

The robot field geologist then turned 0.04 meter (1.31 feet) on Sol 4507 (September 27, 2016), to better position herself over Gasconade. “We did a small adjustment on our position to get everything lined up, and get the arm down on the target and so we'll be here at least a couple of days,” said Stroupe at month’s end.

The plan was for Opportunity to look at the linear outcrop up close with the scientific tools on her Instrument Deployment Device (IDD). But Gasconade doesn’t look like it will easily give up any secrets it may be harboring. “It's a really tough target,” said Squyres. “It's small and very rough and I think it would probably be impossible to RAT. We'll do what we can with this thing and then at that point it will be time to move on.”

The mission had driven down here to check out the Spirit Mound. But the scientists also were looking to uncover more of the most ancient Martian ground, the bedrock that dates to the Noachian Period when Mars had various watery environments.

The rover and her crew first found this ancient ground at Cape York in 2012-‘13 and named it Matijevic Formation, in honor for Mars rover pioneer Jake Matijevic, one of the members of the original MER design team and a chief of MER engineering.

Opportunity’s general location in Marathon Valley was estimated to be about 84 meters (275.59 feet) higher topographically than Cape York. Since the beginning of September, the rover had driven an estimated 59.5 meters (about 195.21 feet) back in geological time. Presumably, the robot is close to the elevation she was at on Matijevic Hill, where the MER mission made history with its discovery.

Now at Spirit Mound however, the ancient bedrock is nowhere to be seen. Opportunity may well be close to that ancient terrain. It’s hard to say. “During these impact events, there is up and down jostling of the rim rock, so it could be that Cape York was uplifted a whole lot more than Cape Tribulation and we were seeing farther down into the stratigraphic column on Matijevic Hill,” suggested Arvidson.

Or, as Matt Golombek, MER project scientist of JPL, summed it: “That jostling during the impact could have changed the elevation if you will of Matijevic Hill.”

“Impacts are pretty catastrophic events and there's a lot of fracturing and vertical lateral movement and there's just a heck of a lot of vertical motion of the rim segments,” explained Arvidson. “Studies of terrestrial impact craters on Earth, like Haughton in Canada, and Gosses Bluff in Australia, and the Nördlinger Ries crater in Germany show this.”

At Spirit Mound, Opportunity looks to be surrounded by more of the Shoemaker breccia she spent the last Martian winter studying in Marathon Valley. Although the scientists are “a little disappointed,” none of them seem to be all that surprised.

Not finding Matijevic Formation was not unusual, according to Arvidson. “I think about a week ago when we could see it, we saw more of the Shoemaker Formation,” he said. “We still wanted to taste it with the APXS and look at it with the MI to see if the characteristics change, but we haven’t found Matijevic Formation,” Arvidson said. “It would have been a long shot to find it.”

The MER scientists aren’t giving up. The one thing they know is that there is more Matijevic bedrock somewhere in Endeavour’s rim. “As we drive toward Cape Byron and then go down the gully, we will exit the gully much farther into the crater than we are now at Spirit Mound,” said Arvidson. “There are a set of benches we'll drive across and one of them could be an outcrop of Matijevic Formation. That's the next best bet.” [A bench or benchland, as it is also known, is a long, relatively narrow strip of level or gently inclined land bounded by distinctly steeper slopes above and below it.]

As the Sun sets on September, Opportunity and the MER team are in good shape and great spirits. Mars is continuing to cooperate and the team, like always, remains optimistic despite the seasonal dust that clouds the air. “The rover is doing wonderfully well,” said Nelson. “We have had no new anomalies since we first had to turn off flash and try reformatting a couple of years ago.”

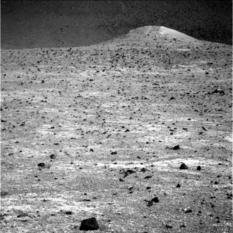

Panoramic glimpse

In late August, early September, Opportunity shot the numerous panels of images that are being stitched together into the MER mission’s next panorama. The oversize “postcard,” which will feature the ridge to the east of Knudsen Ride, on the other side of the Lewis and Clark Gap, is to be officially named and released sometime in early October.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Opportunity’s non-volatile flash drive or long-term memory became corrupted and despite several reformats, the rover’s computer continued to experience faults and unwanted reboots. For more than a year now, the rover has been strictly operating in persistent RAM mode, relying on her volatile or short-term memory.

Basically, that means the robot has to downlink each sol’s work before she shuts down for the night. “While that imposes some constraints on us, it is nothing serious and isn’t holding us back.” Said Nelson. “We are doing a full science mission.”

Once her work at Gasconade is done, Opportunity will rove on, driving southwest through the rim and then angling to motor up a Cape Tribulation slope to targets at the top of the hill. “We looked at traversability and if we were to go any lower here we might not be able to get back out, because the slopes start increasing and it gets sandier down at the bottom,” said Golombek. “You can't drive up a steep slope on sand like you can on bedrock.”

“We'll see how the driving goes,” said Seibert. “Everything looks good so far. If the little backward test steps we did earlier in September are any indication, we should be able to scramble back up without any problems.”

For Opportunity and the MER mission, September was another good month on the Red Planet, one that will likely be remembered as the startpoint for the team’s journey to the first gully ever to be examined on the surface of Mars.

“It feels good to have gotten out of Marathon Valley,” said Squyres, echoing the feelings of most of the team members. “Don't get me wrong. I thought Marathon Valley was a terrific place. It’s just that every time we get to some place new, we want to really explore it and do it right. And then, when we get to the end of that process, it feels really good to be on the road to something else.”

“And that,” added Golombek, “is the really great thing about a rover: you get to keep going someplace new.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth