A.J.S. Rayl • Sep 30, 2011

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Digs In at Endeavour Crater, Team Remembers 9/11

Since leaving the plains of Meridiani, pulling up to Endeavour Crater and checking out its first rock last month, Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity has wasted no time in getting the "new mission" underway. In September, the robot field geologist moved on to its second rock target and dug in as the mission entered its 93rd month of exploring the Red Planet.

For seven and a half years, Opportunity had been driving across a vast plain sculpted in places with fields of beautiful but dangerous sand dunes that resemble waves on a sea, studying environmental conditions of a time long ago when Mars was drying-out. As the rover drove along, it looked at various rocks and topsoil patches to learn what it could from the minerals and grains left behind from that time, enabling the scientists to begin to write the story of how the striking sand dunes that captured the team's interest, and at one point "captured" Opportunity came to be.

Although Mars was dry and wind-blown, there were occasional wet periods then, the scientists believe, and between the wind and the water, the dune fields took on the form of still life sand seas. Year after year, Opportunity found much of the same clues and evidence. That scene changed on August 9, 2011, and in a big way.

As Opportunity moved up and into Endeavour's rim at an area the team calls Cape York, it roved onto ancient terrain, largely buried by lakebed sediments. This terrain is much older than the plains, dating back perhaps to the earliest days of the planet, maybe as long ago as 3.5 billion years ago during the last stages of heavy bombardment, back to when something really big hit the surface and formed Endeavour Crater in an explosive, creative act of the cosmic kind, back to when there was probably a lot more water on the surface.

From data collected by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), a visible-infrared spectrometer onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, some of that water must have been more neutral compared with the highly acidic water for which both Spirit and Opportunity have found good, hard evidence, because phyllosilicates – in particular smectite, a kind of clay mineral – appears to be harbored in the crater rim.

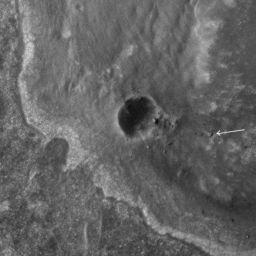

Opportunity on Endeavour's rim

Opportunity on Endeavour's rimThis HiRISE image, taken on September 10, 2011, shows Opportunity sitting atop some light-toned outcrops on the rim of Endeavour Crater, near a smaller crater dubbed Odyssey. When the robot field geologist roved into the crater rim area on Aug. 9, 2011, it also roved further back in Martian time, back to the earliest days of the planet. Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

Where there is water, there is life. So goes conventional biological wisdom. And where there is neutral water, there are likely to be environments that are more life-friendly. “Our hypothesis is that if there are clay minerals, the water was less acidic, and therefore more conducive to life," said Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis, deputy principal investigator for rover science, and a member of the CRISM team.

While CRISM detected the a "subtle but real" signature for smectite about 200-300 meters north of where Opportunity is presently located, and a "motherlode" of the stuff much further to the south at Cape Tribulation, the rover is already "in the thick of the hunt" to find the long-elusive clay minerals, said Arvidson.

This month, Opportunity began making detailed measurements of the chemicals and minerals it could find in a chunk of bedrock on the inboard side of Cape York, dubbed Chester Lake. After looking at the rock in its natural state, natural, it brushed the surface coating off and looked at it again, then ground into with its rock abrasion tool (RAT) and took another look – and it's still looking this weekend to determine the amount of iron that may or may not be rpesent.

In contrast to Tisdale 2, the first rock Opportunity checked out after arriving at Endeavour in August , which boasted plenty of mineralogical evidence that pointed to water moving through and altering its composition,Chester Lake has so far offered the scientists no hint of water alteration.

"It looks like an impact breccia visually," said Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, the MER principal investigator, during an interview earlier today. That's basically a rock composed of broken fragments of minerals or rock cemented together by a fine-grained matrix and formed from the impact of a meteorite or, perhaps then, a planetesimal, one of the small celestial bodies formed during the creation of planets.

"It has sort of a basaltic composition," Squyres continued. "It does not have a zinc enrichment like we saw at [Tisdale 2], so we're stating to think the zinc at the previous location might have been a coating instead of something deep in the rock. We're still thinking about that. It's a work in progress. We're still taking data."

There is a lot of anticipation and hope about finding the clay mineral, the smectite. It would be an incredible achievement for this rover and the MER mission, especially considering it is one of the objectives of the MERs' descendant, Curiosity, slated to launch in November and land in the summer of 2012. Still, the scientists are focused just as much on the big picture. “We’re trying to get the chemical, mineralogical and geological setting," said Arvidson, "so that we can ‘back out’ the ancient conditions and reconstruct environmental conditions during this earlier time period."

10th Anniversary of 9/11 on Mars

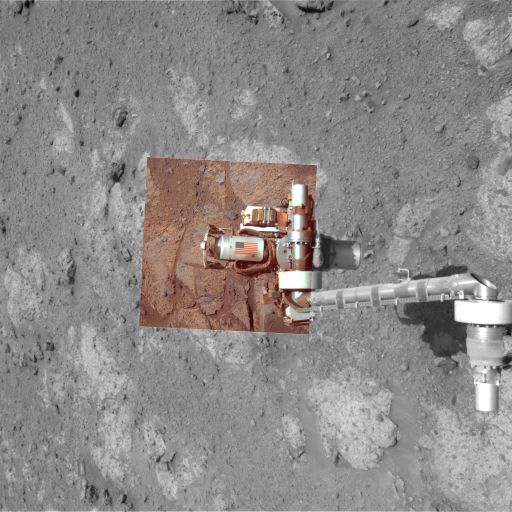

10th Anniversary of 9/11 on MarsThis picture shows an American flag on metal recovered from the site of the World Trade Center towers shortly after their destruction on September 11, 2001. The aluminum component bearing the image of the flag serves as the cable guard of the rock abrasion tool (RAT)built and operated by Honeybee Robotics of New York. Opportunity took the component images that went into this picture on Mars on the 10th anniversary of the attacks on the towers, September 11, 2011. The rover used both its stereo panoramic cameras to record several exposures during its Sol 2713, which were then combined into this one picture. The image is approximate true Martian color, or color as the human eye would see it on Mars. The black-and-white portion of the view, providing context, comes from the rover's navigation camera.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

On Opportunity's Sol 2713 – September 11, 2011 down on Earth and the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York – the rover took a color photograph of the American flag fixed on the aluminum plate that covers the cabling for the rock abrasion tool, which is located at the end of the rover's arm. "On the 10th anniversary we thought it would be a fitting tribute to re-image the cable shield and just remind ourselves of what was there," said Squyres.

Of the countless 9/11 tribute memorials that appeared during the 10th anniversary all across the Earth, each deeply meaningful, this one on Opportunity – and the one on Spirit over in Gusev Crater – hold special significance for the MER team. Beyond being the only known interplanetary 9/11 tributes, the plates on which those American flags are affixed are actually from the New York World Trade Center, recovered in the days after the tragedy in 2001.

"Nine eleven was a horrifying event for everybody," Squyres said. "The way it hit us was that Honeybee Robotics, where some of our hardware was being built, was in Lower Manhattan. The guys at Honeybee watched the towers fall from the roof of their building. It hit us really hard like everyone else. And like everyone else, we felt like we should be doing something."

Locked into an almost impossible schedule for the mission to Mars, there wasn't much they could do. Steve Kondos, an engineer at JPL working with the Honeybee team, came up with the idea of trying to get some metal from the Trade Center and putting it on the vehicle, as an interplanetary memorial, and called Squyres.

"I thought it was brilliant," Squyres wrote in his book, Roving Mars (2005, Hyperion).

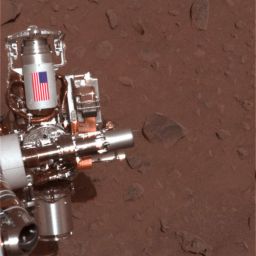

Spirit's 9/11 Tribute

Spirit's 9/11 TributeThe piece of metal with the American flag on it in this image of Spirit is made of aluminum recovered from the site of the World Trade Center towers in the weeks after their destruction. The piece was repurposed to serve as a cable guard for the rock abrasion tool, as well as a memorial to the victims of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and was the first to arrive on Mars. An identical piece is on Opportunity. The abrasion tools were built by Honeybee Robotics in lower Manhattan, less than a mile from the WTC site. Spirit took this image with her Pancam on Feb. 2, 2004, the 30th Martian day, or sol, of her work on Mars.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

One thing led to another and through the contacts of Stephen Gorevan, Honeybee founder and chairman, and a member of the Mars Exploration Rover science team, a representative from then-Mayor Rudy Guiliani's office delivered a parcel of twisted aluminum and a piece of steel beam with bolts in it to Honeybee.

One of the company's lead engineers, Tom Myrick, "the mechanical genius behind the RAT," as Squyres describes him, took one look and had an idea.

With a little help from metalworkers in Round Rock, Texas, under Myrick's watchful eye, the aluminum was refashioned into the plates used to cover and protect the cabling for the RATS.

Back in New York, Myrick added the flags and "tributes" to those who lost their lives during the attack headed for Mars when the rovers launched in the summer of 2003.

"We intended it to be a quiet thing," said Squyres. "The point was not to draw attention to ourselves. It was part of the healing process for our team. We did eventually talk about it … and quite a number of family members of people who perished that day saw that story and we got a lot of positive feedback. It wasn't something we wanted to make a big deal about."

Getting the 10th anniversary picture wasn't exactly easy for Opportunity. "There were complexities and limited power," reported John Callas, the MER project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) 'birthplace' and mission control for the rovers. "We wanted to get the timing and the lighting right and we needed to get it into the plan." No one had to be asked to work overtime. "It was a small gesture," said Squyres. "But it was an important one."

Now, as September falls to October, Opportunity remains remarkably vital good health more than seven and a half years after bouncing to a landing in its very first crater in January 2004. The overland expedition of this desolate, cold, unforgiving planet has taken its tolls. The rover's shoulder joint is broken, its miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) was declared lost this month, the Mössbauer takes weeks to detect iron these days, and the steering on one of the wheels is toed in a bit, but Opportunity roves on, backwards most of the time, and the engineering and science teams have pretty much reinvented the word 'workaround' to meet challenges confronted along the way.

"Opportunity is still in very good health," reported Bill Nelson, chief of the rover engineering team at JPL. "She has not experienced anything bad in quite a while – the Mini-TES was lost but it's been out of commission for a long time – so the overall health of the vehicle is unchanged, which is to say still quite robust."

And you won't find a more skilled or enthusiastic team of rover drivers anywhere on Earth.

The next big challenge is the coming Martian winter, which is already beginning to put the chill on. The winter solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars, where Opportunity's site is located, will occur on March 31, 2012. [A Martian year is approximately twice as long as an Earth year, and the four seasons on Mars are about twice as long as on Earth.]

"We are looking longer term at the next winter," confirmed Callas. "We want to figure out where we want to position Opportunity such that we can maintain the highest level of activity during the winter and have scientifically interesting sites to explore."

"There is a fair amount of dust on our solar arrays and it looks like this winter Opportunity will have a more difficult time of it than she has ever had in the past and it is of concern to us," elaborated Nelson. "We've put together a Winter Planning Team to begin gathering data. It may turn out that we'll be able to continue operations throughout the winter. Or it may be that things are not that good and we may have to find a place with a good northerly tilt as a winter haven and park there."

During the Martian wintertime in the planet's southern hemisphere, the Sun is low in the northern sky and the MERs' solar arrays are not movable. However, the rovers were designed to be able to climb a slope and reposition themselves in order to angle their solar arrays directly to the Sun in order to take in as much photon fuel as possible during those sols when the sunlight is scarce.

While Opportunity has been able to work and rove throughout the last four Martian years, winters on the Red Planet are never considered lightly. By most best guesses, it was the Martian winter that is ultimately responsible for taking out Spirit.

Since Spirit landed and explored further south of the equator than Opportunity, it never had a choice but to find a north-facing slope and a haven in which to hunker down for the winter, soaking up whatever Sun it could just to survive. In the beginning of the mission in fact, the general consensus held that Spirit would not even survive the first winter. Being unable to reposition itself last winter may well have been why Spirit never phoned home after presumably going into a hibernation mode in March 2010. The rover may have just gotten so cold, parts gave out.

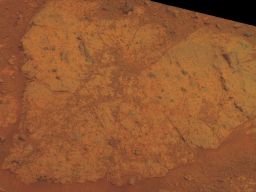

Chester Lake in natural Martian color

Chester Lake in natural Martian colorChester Lake is about 3 feet (1 meter) across. It lies on the inboard or southeastern side of a low ridge known as Cape York, which forms a portion of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. Rover team scientists chose it for inspection because it is in-place bedrock that appears to be representative of a region of outcrops on the inboard side of Cape York. Chester Lake differs from the first rock inspected by the rover on Endeavour's rim, Tisdale 2, a boulder excavated during an impact event that produced a small crater on the rim, although both rocks appear to be breccia, a type of rock fusing together broken fragments of older rocks. The view is presented in approximate true color. This "natural color" is the rover team's best estimate of what the scene would look like if humans were there and able to see it with their own eyes. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

This coming Martian winter will be Opportunity's fifth, and everyone is keenly aware that the rover is getting way on in robot years. Add to that the 'uncertainty principle of Mars,' and, well… every sol is a gift.

"During the last 30 days, the dust has increased and the dust factor has gotten worse a little faster than the projection made in August indicated it would," reported Nelson. As a result, the rover's energy dropped a little more this month, and power levels are now hovering around 315 watt-hours, about one-third the power of a "fully charged" MER. "For a solar-powered vehicle, this is always a concern," Callas acknowledged. "Less energy each day means less activity each day, less driving."

Right now, Opportunity has plenty of power to drive and once the rover is finished at Chester Lake, it will head north to Shoemaker Ridge, named for the late, great, and much loved Gene Shoemaker, the "father of planetary sciences," discoverer of comets, mentor and inspiration to explorers everywhere.

The Planetary Society's Gene Shoemaker NEO Grant program seeks to assist amateur observers, observers in developing countries, and under-funded professional observers contributing to vital NEO research. Since 1997, the Society has awarded 38 Shoemaker NEO grants totaling more than $235,000 to observers from 15 different countries on 5 continents.

"There are indications that we may see higher concentrations of phyllosilicates as we work our way north and that's the reason we're going to head in that direction," said Squyres. "We'll do the best we can. But we don't know where the phyllosilicates are for sure. We'll find what Mars gives us – and heading up toward Shoemaker Ridge is definitely what's next."

September proved to be something of an emotional month. Beyond the 9/11 anniversary, naming the ridge for Gene Shoemaker is something that seems to have deeply touched the MER team, so many of who knew Shoemaker.

"As we've gone through this mission, one thing that I have felt over and over again is how much Gene would have loved this," reflected Squyres. "He would have really, really had fun with this mission and especially the rocks that we're in now. Gene contributed more than any other scientist to our understanding of impact processes and how important they are across the whole solar system, including on Earth. And to see these beautiful impact breccias – it just really seemed appropriate that we name something here after Gene."

And so: Shoemaker Ridge.

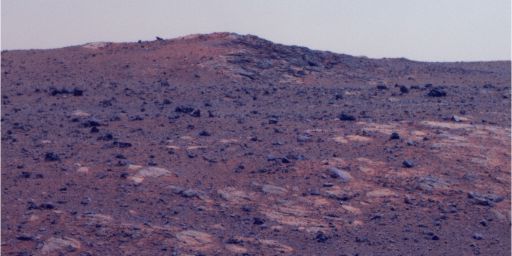

Shoemaker Ridge

Shoemaker RidgeOpportunity took this picture of the southern extremity of Shoemaker Ridge with her stereo panoramic camera on her Sol 2715 (Sep. 13, 2011). The Pancam team processed it in false color to bring out the detail. "The outcrop on the southeast side in the picture is Boston Creek," noted Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator for rover science.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

But that's not all. "There will also be the type locality for all of the rocks in this location that we're going to call the Shoemaker Formation," Squyres added. "It's a fitting thing to do."

As October scares its way onto the calendar, the MER team will begin generating some highly detailed, topographic maps of the area to find all the possible north-facing slopes on which Opportunity can position itself with solar arrays toward the Sun.

If the rover can achieve just a 15-degree slope, said Callas, then Opportunity should be able to rove throughout the season and into spring no problem. The team's projections and predictions are being refined and updated every month and ultimately only time – and Mars – will tell.

Opportunity From Meridiani Planum

After completing an investigation of Tisdale 2, the first rock target at Endeavour's rim, in August, Opportunity spent the first week of September getting close to her next rock target, a chunk of outcrop on the inboard side of Cape York called Chester Lake.

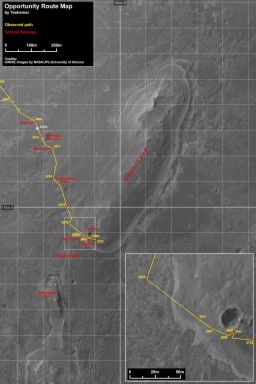

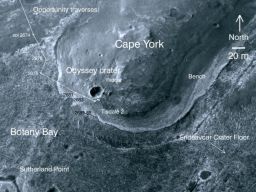

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapEduardo Tesheiner created this Opportunity route map from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. It shows the rover's travel to its Sol 2703 (Sep. 1, 2011) and approximate location. The rover officially reached the rim of Endeavour Crater on Aug. 9, 2011.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / MSSS / E.Tesheiner

While the skies overhead remained pretty hazy – the rover reported a Tau of 1.00 – the rover began September with acceptable power levels of around 336 watt-hours, plenty of energy for the driving and science and engineering tasks on her agenda.

Opportunity literally roved into September on her Sol 2703 (September 1, 2011) with a 27-meter (89-foot) drive to the northeast toward Chester Lake. The MER scientists chose this particular rock because it offered several easy-to-access targets for the rover to conduct some in-situ or contact investigation with the microscopic imager (MI), alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), and the Mössbauer spectrometer.

Opportunity completed the jaunt to Chester Lake on Sol 2707 (September 5, 2011) with a 20-meter (66-foot) drive, then took care of the usual science and routine engineering tasks.

Since the objective for Opportunity at Endeavour is to find the ancient rocks on Mars and "because we moved from layered sedimentary rocks to old, old rocks," the MER team has chosen to name targets in this area after places in, near, around the Abititi Greenstone Belt that spans the Ontario-Quebec border in Canada, said Arvidson. A greenstone belt is formed of ancient rock, or Archean rock and is so-named because of the green hue of the metamorphic minerals within the mafic rocks. Typical green minerals in greenbelts include chlorite, actinolite, and other green amphiboles.

The Archean is a geologic eon before the Paleoproterozoic Era of the Proterozoic Eon, before 2.5 billion years ago when volcanic activity was much more active than today. Most surviving Archean rocks on Earth are metamorphic or igneous, with granitic rocks predominating throughout the crystalline remnants of the surviving Archean crust.

One of the world's largest Archean greenstone belts, Abititi is estimated to be between 2.8 to 2.6 billion years old. While it is mostly made up of volcanic rocks, it also includes ultramafic rocks, mafic intrusions, granitoid rocks, and early and middle Precambrian sediments.

As the second week of September began, Opportunity bumped forward a little more than a meter (3 feet) on Sol 2710 (September 8, 2011) to put some of Chester Lake's surface targets within reach of her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm. Then, she settled in for a while.

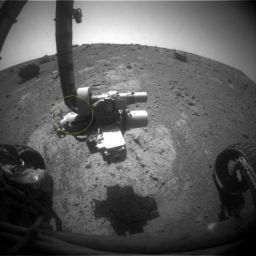

Flying free on Mars

Flying free on MarsOpportunity took this image recently with her front hazard cameras (HazCams), capturing the 9/11 tribute flying free on Mars. Look to the bottom left of the arm and you will see the American flag inside the yellow circle, which Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com added. The flag is affixed to the cable covering for the rock abrasion tool, which the rover used this month to check out Chester Lake. For more of Atkinson's work: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/2011/09/Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

On Sol 2713 (September 11, 2011), the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, Opportunity worked with her ground crew to position her stereo panoramic camera (Pancam) at just the right time, in just the right light to take a color photograph of the American flag on the aluminum plate that is the cable covering for the rover's rock abrasion tool, designed and built by Honeybee Robotics of New York.

The aluminum covering that bears the American flag was recovered from the New York World Trade Center site after the 9/11 attack in 2001, and repurposed into the cable covering plate as a tribute to those who died that day. Spirit, now parked in perpetuity at Gusev Crater, carries the exact same tribute, made of the same recovered metal.

Back in September 2001, Honeybee Robotics employees in lower Manhattan were working on the rock abrasion tools for Spirit and Opportunity, the scientific instruments with which the twin rovers would grind into the rocks. When the first plane, and then the second hit the twin towers of the World Trade Center, less than a mile away, it shook the lives of those employees and the MER team, as it did people around the world.

That morning, Honeybee founder and chairman Stephen Gorevan, was six blocks from the World Trade Center riding his bicycle to work, when he heard an airliner hit the first tower. "Mostly, what comes back to me even today is the sound of the engines before the first plane struck the tower. Just before crashing into the tower, I could hear the engines being revved up as if those behind the controls wanted to ensure the maximum destruction. I stopped and stared for a few minutes and realized I felt totally helpless, and I left the scene and went to my office nearby, where my colleagues told me a second plane had struck. We watched the rest of the sad events of that day from the roof of our facility."

At Honeybee's building on Elizabeth Street, as in the rest of the area, everything went into a slow motion blur in the aftermath of the attack. The "acrid, plastic-metallic burnt smell" from the collapse of the towers persisted for weeks.

The tight schedule for the MER mission meant that those working on the instruments could not spend much time helping at shelters or in other ways to cope with the life-changing tragedy of 9/11. "But we felt like we needed to do something," said Squyres.

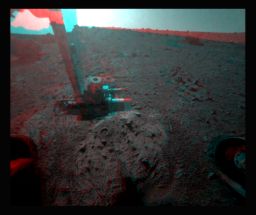

Salisbury at Chester Lake in 3-D

Salisbury at Chester Lake in 3-DGet your blue-red glasses and check out this picture of the hole Opportunity ground into Salisbury this month, which Stuart Atkinson rendered in 3-D. Salisbury is a target on the Chester Lake bedrock at Cape York, which the rover continues to examine as September turns to October.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

Steve Kondos, who was at the time a JPL engineer working closely with the Honeybee team, called Squyres one day with the notion of trying to get some metal from the wreckage and fly it to Mars on the rovers as an interplanetary memorial. Squyres set the wheels in motion.

First, the team would have to acquire an appropriate piece of material from the World Trade Center site. Truckloads of debris were still driving by the Honeybee offices everyday. They could have just taken what they needed. "But if we were going to do this, we couldn't build a memorial by going Dumpster diving, or by gabbing something off the back of a truck. We had to do it right," Squyres remembered in Roving Mars. As Gorevan told him on the phone: "We're touching something sacred here."

Through Gorevan's contacts, then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani responded to the request that have found its way to him in the week morning hours of November 30th. The next day one of his representatives arrived at Honeybee, a parcel in hand. "It was actually delivered directly to Honeybee," remembered Arvidson.

Inside the parcel was a simple handwritten note from Richard Sheirer, who ran the office of emergency management at Ground Zero: "Here is debris from Tower 1 and Tower 2."

Tom Myrick, an engineer at Honeybee, saw the possibility of machining the aluminum into the cable shields for the RATs, and in short order hand-delivered the material to the machine shop in Round Rock, Texas, which was working on other components of the tools. There, metalworkers re-shaped the aluminum into covers for the cabling for the RAT on both Spirit and Opportunity. Once the shields were back in New York, Myrick affixed an image of the American flag on each, tested them to make sure the decals would stick, and they were ready to fly.

Spirit and Opportunity launched in the summer of 2003 and landed in January 2004, completing their three-month prime missions in April 2004. Nobody on the rover team or at Honeybee spoke publicly about the cable shields that so prominently featured the American flag, or about the source of the metal until later that year. "It was meant to be a quiet tribute," Gorevan told a New York Times reporter writing a November 2004 story about Manhattan's participation in the rover missions. "Enough time has passed. We want the families to know."

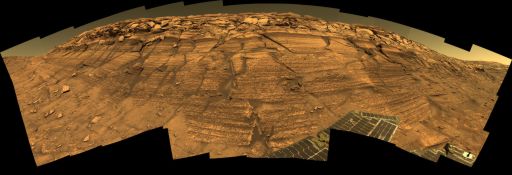

Endeavour in September

Endeavour in SeptemberOpportunity captured the images that went into this panorama of Endeavour Crater on Sol 2715 & 2718 (Sep. 13 & 16, 2011) and James Canvin, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, processed it. For more of Canvin's work, go to: http://nivnac.co.uk/mer/Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / J. Canvin

The unique way in which the MER team and the Honeybee Robotic team were able to pay tribute to the thousands of victims who perished in the attack has become deeply meaningful to the family members of those who died that day and to countless Americans and explorers around the Earth, as well as the rover team members. "One friend who had a direct personal loss on that day wrote to us and was very appreciative of what we did in showing how as Americans we can still show our best even after experiencing a serious tragedy," said Callas. Past that, Squyres said, it's between those individuals and us, and I'd like to leave it at that."

It's been 10 years, but even for those who weren't in New York that day, the emotions still run strong and deep. On that September 11th, every American was a New Yorker.

As Opportunity's picture of the tribute, taken on the 10th anniversary, hit the media, Gorevan reflected: "It's gratifying knowing that a piece of the World Trade Center is up there on Mars. That shield on Mars, to me, contrasts the destructive nature of the attackers with the ingenuity and hopeful attitude of Americans."

The team worked overtime and put their all into getting that picture, said Callas. "It was something we felt was very important," added Squyres.

Chester Lake

Chester LakeChester Lake is about 1 meter (3 feet) across. It lies on the inboard or southeastern side of a low ridge known as Cape York, which forms a portion of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. Rover team scientists chose it for inspection because it is in-place bedrock that appears to be representative of a region of outcrops there. By Sol 2713 (Sep. 11, 2011), Opportunity had used its microscopic imager and alpha particle X-ray spectrometer to study Chester Lake, and later used the rock abrasion tool and Mössbauer spectrometer on the rock. The scientists will use all the data to reconstruct the chemistry, mineralogy and geologic setting of Chester Lake, including evidence about whether or not the rock has any clay minerals in its composition.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Afterwards, Opportunity got back to work, collecting MI pictures of surface targets at Chester Lake that sol, and then placing her APXS on the surface for an overnight integration. Two sols later, on Sol 2715 (September 13, 2011), the rover performed a seek-scan with the RAT in preparation for brushing a surface target with the RAT

As the third week of September took hold, Opportunity continued her investigation of Chester Lake, and on Sol 2717 (September 15, 2011) brushed the rock at a spot called Salisbury 1 in order to take a closer look inside. She followed that by taking out her MI and snapping a series of pictures for a close-up mosaic, and then put her APXS on the brushed area for an overnight integration of the freshly brushed surface.

Two sols later, on Sol 2719 (September 17, 2011), Opportunity used her RAT to grind the surface target, took another series of MI pictures of the freshly ground surface of Salisbury 1. On Sol 2722 (September 20, 2011), she took some post-grind images of the RAT grind bit to check its condition, and then placed the APXS onto the RAT hole to see if there might be any changes with depth.

The last week of September proved a little frustrating as the MER mission suffered the loss of two uplinks. The plan for Sol 2724-2725 (September 22-23, 2011) never made it to Opportunity because the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter went into safe mode and MER gave up its DSN track to the effort of restoring its orbiting colleague.

Just three sols later, on Opportunity's Sol 2728 (September 26, 2011), a "beam current problem" occurred just before MER communications window was scheduled to open and so DSN operators were unable to send the uplink. "With such short notice there was no way of getting a replacement," said Nelson. "There's not always a replacement and in this case it was only a 20-minute window. They can't bring a station up in that time even if one is available, and so that uplink was lost as well."

On Wednesday, Sol 2730, Opportunity completed a poker test with the MI to check on its performance, and then began a series of Mössbauer integrations to try and determine the iron content of Chester Lake. Since this spectrometer has a radioactive power source that has diminished with time, what once took a few hours now takes weeks. Iron, however, is an important "constituent" in determining whether the rock has been altered by water, so the rover will do what it can to try and tease out the secrets embedded in Chester Lake.

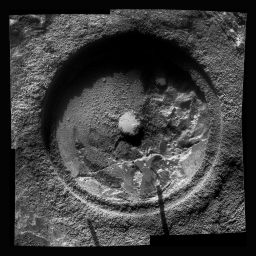

Salisbury RAT hole

Salisbury RAT holeOpportunity took this picture of the hole that she ground into Chester Lake at Salisbury on Sol 2721 (Sep. 19, 2011). The Pancam team produced this picture in true Martian color, or at least the color most of humans would see if standing there on Mars looking at the rover's work.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

"The half-life with the radioactive source is way down so we have to do at least three evenings of integration to tell anything at all from the signals," said Arvidson. Therefore, as the calendar turns to October this weekend, Opportunity, with 33.58 kilometers (20.86 miles) now on her odometer, will continue the Mössbauer integrations. "We'll integrate for a few sols, look at the data, and then decide whether or not it's worth continuing to integrate or call the experiment a success and button up and go to the next area."

At this point though, the scientists are pretty well convinced that the rock is an impact breccia. "We have looked at Chester Lake's natural surface, brushed surface, and RATed surface with MI and APXS," said Arvidson. "Interestingly, and in contrast to what we saw out on the plains and in contrast to rocks at Gusev, we see very little evidence for change with depth," he pointed out.

"If we go back to [rocks examined] prior to Victoria, when we ground into some of the sulfate rocks, you may remember that we saw changes in some of the elements with depth," Arvidson continued. "Back on the Gusev plains where we ground into Mazatal, which was one of the hard rocks, or Humphrey or Adirondack, we saw chemical changes with depth. And we saw coatings on the rocks. But so far we have seen no changes with depth and there's not a coating on Chester Lake."

One reason for that, the scientists think, is because Chester Lake is soft and breaks down into constituent grains, thus is unable to develop or retain any kind of outer rind or weathering. "At least that's one observation and inference," noted Arvidson. "The other is that the rock kind of looks basaltic. "It's as if you took a whole bunch of basaltic soil and then just made it into a breccia, a glomeration of fine-grained matrix and some chunks that are probably basaltic chunks."

No evidence of water is popping up in the rock. "But we have precious few capabilities to tell yes or no," Arvidson noted. "What we are focusing on is the nature of this material and it's likely origin. Chester Lake is an outcrop favorable for IDD work, including brushing and RATing and that's the approach we took. It's not finding the clay minerals, but we didn't expect to see those here. So far, this rock looks to be part of the impact process that produced Endeavour and it's representative of the ancient Noachian rocks and that's pretty exciting, at least I think it is."

If Opportunity returns data from its Mössbauer work that indicates Chester Lake has "some interesting mineralogy pointing to alteration in a water environment, such as oxidation of the iron and the presence of phases, like goethite (FeOOH), which forms in the presence of water," the scientists might decide to stay longer and conduct more integrations with the spectrometer, Arvidson said. [Goethite, you may remember, was the first aqueous mineral Spirit found after roving from the plains of Gusev up into West Spur on Husband Hill.] But if Opportunity returns no interesting mineralogy from the Mössbauer, the rover will move on next week.

Salisbury post-RATing

Salisbury post-RATingOpportunity took a ries of close-up pictures of the Salisbury RAT hole this month with the microscopic imager. Stuart Atkinson produced this picture by stitching four of those shots together and enhancing and sharpening the final product. Click and enlarge it to see the detail. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

"This is really detailed detective work now," said Arvidson. "If we had our druthers, we'd have the Mini-TES working and be mapping the heck out of the surrounding outcrops, but it doesn't work. And if we had our druthers, we'd be doing multiple Mössbauer observations, but what took us three hours at the beginning of the mission now takes three weeks or more."

And time on Mars is always something of the essence. The smectite is beckoning and the scientists would love to have Opportunity find the hard evidence sooner rather than later. The area at Cape York where CRISM detected the "subtle but real" signature for smectite lies another 200 meters to the northeast – and Opportunity will likely be heading there, if all goes as hoped, during the next several weeks. But the next immediate destination for the rover is Shoemaker Ridge, named for the legendary Gene Shoemaker.

"We're going to first go up to Shoemaker Ridge, which is about 30-40 meters to the north," confirmed Arvidson, who is also a member of the CRISM team. As important as finding the clay minerals and getting as detailed a "picture" as possible of the ancient environment that was once there, so too is getting a good read on Endeavour Crater.

"In terms of geologic relevance, we are actually characterizing for the first time in situ material associated with a 20,000-meter diameter impact crater," explained Arvidson. "We're sitting on the eroded-down rim and characterizing those eroded down properties."

Shoemaker Ridge may be associated with a change in geology and chemistry of Cape York and the scientists have already planned for Opportunity to look for that type bedrock representative of what will be called the Shoemaker Formation, with Shoemaker Ridge being a kind of anchor feature. "We'll soon find, I think in the next couple of months, one of these sites that will be what is called the type area or type outcrop for what will be the Shoemaker Formation," offered Arvidson.

The team named the hematite and sulfate-salt rich sedimentary bedrock extending for hundreds of kilometers in Meridiani Planum the Burns Formation, after Roger Burns, the MIT professor, and one of the first scientists to recognize the importance of sulfur and sulfates, particularly jarosite, on Mars "long before Opportunity landed," as Arvidson put it.

Now, here at Endeavour, Shoemaker simply made sense. "Gene is the 'father of planetary sciences' effectively, and was very fundamental in terms of understanding impact processes. So dude! Here we are on the rim of a 20,000-meter impact crater and see an impact breccia," Arvidson underscored. "Naming the ridge and [subsequently the formation after Shoemaker] all fell into place. We all came to the same conclusion."

Burns Cliff Panorama

Burns Cliff PanoramaOpportunity scrambled slowly across the steeply sloped wall of Endurance Crater to reach Burns Cliff, a vertical pile of finely layered rocks that was irresistible to the rover sceintists. From this precarious position it captured a 7-color panorama from her Sols 287 to 294 (Nov.13 to 20, 2004). The bulging appearance of the wall was due to the rover's very close position to it; in reality the view spans about 180 degrees and the wall is gently concave. For the full-resolution image, visit the Pancam website.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell

In coming sols, the MER team will be preparing for the next winter, investing time in map-making and weather predicting, such as that is possible on Mars. Currently, Opportunity is on the inboard side of Cape York, and the long axis of Cape York strike southwest/northeast, so the vehicle is tilted to the southeast, not the best angle for the solar arrays, one reason the rover's power levels are in the low 315-335 watt-hour range. For now, that's still enough power for the rover to cruise through her sols, but as the temperatures drop and more power is required to stay warm, the rover's power levels will drop.

"Winter on Mars and power are always issues," said Callas. "It's like when you have less money coming in, you can't be as extravagant," he added, using an analogy most people can relate to these days.

Earlier predictions had indicated that Opportunity could eke through winter, roving here and there, without special precautions. "But projections change and they depend heavily on things that are difficult to measure," Nelson pointed out. "For example, it's hard to know how much dust accumulates on the array every day. It's a tiny amount, but it doesn't take much change to that tiny amount one way or the other to compound over the next say 200 or 300 sols to give you a very different power situation," he explained.

Historically, a lot of dust gets whipped up into the atmosphere during the Martian spring and summer and then that dust "rains" down. "The atmosphere acts as a kind of integrator, and so the dust spreads out through the atmosphere and filters out at a more or less constant rate, but we usually see it level out during the winter," said Nelson. "Even so, it means that we're making guesses as to when it's going to level out and we're making guesses as to how much dust will actually fall out over every 30 or 60 day period."

Mars at opposition in 2001

Mars at opposition in 2001From the Hubble Space Telescope, Mars is a world with a diverse surface, clouds, and climate. This image was captured during Mars' opposition on June 26, 2001. Credit: NASA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

As the engineers accumulate new data, they produce more refined predictions. "We're incorporating each preceding month's experience into the next prediction and we'll continue to do that for months to come," Nelson said. "But I would not be at all surprised to see this thing yo-yo back and forth between things are looking better and things are looking worse. We could also have it yo-yo from things are looking worse to things are looking more serious."

Opportunity has never had to worry about finding a north-facing slope for winter before, but if it does have to find safe haven this winter around, the team has plenty of experience with Spirit, which always had to find a north-facing slope just to survive the Martian winters.

"We've done some lily-padding with Opportunity from time to time, which typically means finding some place that has a number of north-facing slopes and interesting science and the rover drives from one north-facing slope to another," Nelson said. "But that strategy has been motivated more by the fact that we were on adverse slopes, and so we looked for those patches of good slope, or at least better slope to try and keep us moving. Opportunity has never had to park for the winter like Spirit did," he said.

The objective of course is to keep Opportunity roving through the next winter solstice on March 31, 2012 and on into the next Martian spring. To that end, the MER engineers are scouting all the nearby regions where the slopes tilt to the north, said Callas. "We're going to be generating some more detailed slope maps to assess where we may want to position the rover. We're going to be looking at options, some close by, some further away to see where we want to be. There's a lot of science to do at Cape York and we're looking at locations that would keep us in this area, so if we don't complete that science before winter, we can complete it after winter – or during the winter period," he said.

Opportunity's next stop, Shoemaker Ridge, will provide a vista that will give the rover the view of her robot lifetime, as well as a prime location to do some serious imaging for mapping those nearby north-facing slopes. It could be that the rover hangs out through winter on and around Shoemaker Ridge, which is "a bump along the long axis," noted Arvidson. "A bump by definition has to have a southern part and a northern part, so there are northern slopes there, the question is how steep they are, and how accessible they are."

According to the latest assessment, Opportunity could continue to move around throughout the coming winter as long as she stays on north-facing slopes – "very similar to the first winter for Spirit, where we were on a north-facing slope [on Husband Hill] and were still able to continue to drive and move the vehicle," Callas informed. "That's what we're targeting." If Opportunity can achieve a 15-degree slope to the north at least through the worst of winter, she could continue to move every day. "Less than that, then we might have to park the rover for a period of time," he said.

First neighborhood at Endeavour

First neighborhood at EndeavourThis image taken from orbit shows the path Opportunity drove in the weeks around the rover's arrival at the rim of Endeavour Crater. The sol or Martian days are indicated along the route. For example, Sol 2674 corresponds to Aug. 2, 2011; Sol 2688 corresponds to Aug. 16, 2011. The route leads to a rock dubbed Tisdale 2, which is a block of material ejected by an impact that excavated the small crater called Odyssey on an are of the Endeavour rim the team calls Cape York. The next Endeavour rim fragment to the south is called Sutherland Point, and a gap between Cape York and Sutherland Point is called Botany Bay. The base image of the map is a portion of an image taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) instrument onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, on July 23, 2010.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

The threat of the looming Martian winter is causing a slight tension between the scientists and the engineers about this issue. "The scientists would really like to get to new territory, and the northern end of Cape York is where MRO has detected from orbit the signature of phyllosilicates [smectite], but it doesn't look right now like there are any great north-facing slopes on the north end of Cape York," said Nelson. "It's just not that big of a feature – not that high – and so the slopes are really rather gentle and where they're not quite so gentle, they're also not quite so northerly. So while we have detected little patches that may be north facing, this is not an area where we could find a good winter haven should that be necessary."

That leaves south as the other option. "We are looking at sites where we would leave Cape York and dash south and cross Botany Bay to places like Nobby's Head or even further," said Callas. "But we're still very early in this process and we really don't have the information yet to make these decisions. We are gathering that information now."

Nelson confirmed that. But there's a rub with that southern option. It means leaving Cape York sooner, and Nobby's Head doesn't have quite the same sci-appeal as Cape York. For the time being, there is time, and so far, the scientists are prevailing and it's onward to Shoemaker Ridge.

Fortunately, Opportunity continues to show her MER mettle and seems game for just about anything. "She's in good health, we are continuing to explore, and are very happy with her performance actually," said Nelson.

That bodes well for the mission, because the story of Endeavour is going to take a while to write. "It's going to take a lot of detective work," reiterated Arvidson. "People need to be patient."

If that sounds vaguely familiar, it's exactly what team members said back in 2004, at the beginning of the "old" mission.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth