A.J.S. Rayl • Sep 30, 2010

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Snoozes through September , Opportunity Bolts Past Halfway Mark to Endeavour Crater

As Opportunity picked up the pace to Endeavour Crater this month and crossed the halfway point on the long journey from Victoria Crater and Spirit continued sleeping in hibernation mode, the Mars Exploration Rovers chalked up their 81st month of what was supposed to have been just a three-month tour of the Red Planet.

“There’s been no word from Spirit,” confirmed Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis. “We’re still kind of in that try-everyday-and-wait-and-see strategy,” added Scott Maxwell, rover driver team lead at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where Spirit and Opportunity were “born. “We haven’t heard from the rover since March, so we don’t know at all what’s going on with her.”

Surviving its fourth harsh Martian winter has been, by all accounts, Spirit’s toughest challenge to date. The fact that the rover had been unable to extricate itself from a sandy pit and get to a favorable slope to tilt its solar arrays to the Sun before the winter cold took hold has made the challenge even more difficult.

Once the low angle of the late Martian fall and early winter sunlight severely limited the solar-powered rover’s ability to generate power, to the point where Spirit didn’t even have enough energy to wake up and communicate, the rover shut everything down except the mission clock and emergency heaters for the main power batteries. Then, if she followed the program, went into a low-power or "hibernation" mode. But the last time MER mission controllers heard from Spirit was more than six months ago, on March 22.

Not long after that, NASA and JPL engineers began -- and continue -- listening for Spirit to wake-up from its low-power fault and go into autonomous recovery, even though they really didn’t expect to hear from the rover for months.

Then, a few months ago, after new models of Mars indicated that it was possible Spirit got so cold and lost so much power that its mission clock might have also faulted and shut down, the rover engineers initiated another strategy of pinging the robot field geologist instead of just waiting for it to phone home.

If the rover’s clock stopped, Spirit has no idea what time it is -- and that would change the way in which the ground team would have to re-connect with the rover. To cover that possibility, the team has been reaching out to the sleepy robot field geologist with a series of commands in a procedure they call sweep-and-beep since July. “Each command is designed “to nudge or prompt the rover to respond, if indeed Spirit has tripped the mission clock fault,” said Bill Nelson, MER rover engineering team chief at JPL. So far -- not a beep has been heard from Spirit in more than six months.

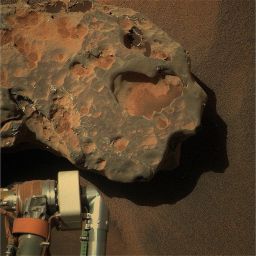

Oileán Ruaidh in living Martian color

The big science news of September 2010 was that Opportunity happened on another gnarly iron nickel meteorite. The discovery of Oileán Ruaidh stirred the robotic romance in rover poet Stuart Atkinson, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com. Here, in a world exclusive is a sneak peek of Atkinson's latest poem:

"Oileán Ruaidh & Her Sisters"

. . . Hard to believe this gnarled and ugly nugget

Of elemental iron once sailed silently between worlds,

Tumbling over and over, soaked in starlight,

Bathed in the Milky Way’s glow until one long-ago,

Twin moon night it fell screaming from the sky

To slam into Old Meridiani like Kal El’s capsule into The Kents’ cornfield . . .

The poem in its entirety can be found tomorrow, October 1, 2010, at Atkinson's Road To Endeavour blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Image Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / colorized by Stuart Atkinson

For the MER team, it hasn’t been much of a surprise that September proved to be another quiet month for this rover. While the advancing springtime in the southern hemisphere of Mars is beaming stronger rays of photon “fuel” down on Spirit’s solar panels and power levels are believed to be improving, atmospheric conditions historically deteriorate during the Martian spring. It’s the season when the planet’s notorious winds can whip up, sometimes intensely, stirring up the powdery rusty-red dust and causing the skies to get hazy enough to cancel out any boost in energy from the increasing amount of sunlight.

Based on models of Mars' weather and its effect on available power, a response from Spirit might have arrived this month, but most engineers have been consistently predicting the rover would wake up in October or November. Team members continue waiting patiently and nothing seems to have dampened the collective belief that they will hear from Spirit soon. “Our early projections were that maybe the rover would beep in mid-September, with the more likely time mid-October or later,” reminded Nelson. For now, “everybody’s focusing on Opportunity,” said Arvidson.

On the other side of Mars, Opportunity really picked up the pace at Meridian Planum, literally zipping over patches of bedrock and past the halfway point to Endeavour Crater this month. “Outcrop is just generally better for driving, because there’s less soil -- the wheels like it better Opportunity’s visual system likes it better,” noted Maxwell.

Back in September 2008, when Opportunity pulled away from Victoria Crater and headed out on the 19+-kilometer journey across the Meridiani plains to Endeavour, the assignment seemed more than a little ambitious.

Now -- with the hills of Endeavour looming ever larger on the horizon, miles of seemingly friendly terrain ahead, and Opportunity burning up the plains sol-after-sol with one extended sprint after another this month -- the destination suddenly seems realistically in reach.

The drive limits imposed last year on Opportunity because of its chronic, ‘hot’ right front wheel were eased this month, ‘unleashing’ the rover to drive as much as 140 meters in one sol if it can, thus doubling the 70 meters to which it had been restricted. “We haven’t been doing any drives that are getting us that far yet, but 140 meters is a number we can probably hit and it’s going to be a nice comfortable distance for us,” said Maxwell.

That’s not all. The rover drivers are talking about some other “tricks” that would enable Opportunity to drive even farther and “faster,” Maxwell added, saying there are a couple of ideas being worked in the pipeline. It will take tens more meters, however, for this rover to beat its own record of 220 meters, made back in 2005, “before the Purgatory embedding,” recalled Nelson.

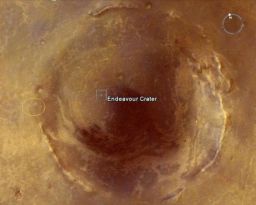

Opportunity's port at Endeavour

Opportunity's port at EndeavourThis image taken by the University of Arizona's High Resolution Imaginging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO)gives you an idea of where the MER team plans to have Opportunity pull up to Endeavour Crater. At least for now, this is general area where the rover is slated to arrive and begin its tour.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / UA / labeled by Stuart Atkinson

At about 22 kilometers (13.67 miles) in diameter, Endeavour is about 28 times wider than Victoria Crater at 800 meters (a half-mile) in diameter, and on this crater-hopping part of the MER mission, size does matter. More than an impressive landmark to behold in orbital images, Endeavour’s humongous size indicates that this big hole in the ground holds secrets of a more ancient Mars, a time long, long ago when the planet just may have been habitable by life.

As the MER luck would have it, the story in recent months got better and the next big attraction became even more compelling when scientists working with the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer (CRISM) instrument onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter found hydrated sedimentary rocks near Endeavour and clay minerals on its rim. Both these rocks and clay minerals are evidence of past water and by extrapolation past habitable environments. Moreover, no mission has ever studied this evidence up-close, on the ground -- although the next rover, the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), aka Curiosity, is being sent to do just that. In fact, the race between MER and MSL was declared “on” in last month’s MER Update, so Opportunity is looking to make history once again.

Even before Opportunity’s rest last weekend, when the rover examined another iron nickel meteorite, the science team settled on a generalized agenda that limits the science stops from here on -- unless, of course, something really intriguing changes the scientists’ minds. “The general plan is to make a beeline to Endeavour,” said Arvidson, “because we just don’t know how long Opportunity will live.”

Despite being a robot, the rover still has to stop now and again to rest for a while, and there are a few chosen targets and planned studies on Opportunity’s science agenda between its present location and Endeavour, including a “fresh crater” called Santa Maria, Arvidson said. The rover will also make a couple of stops to sample bedrock and a couple of stops to sample soil for the ongoing study of the surface, and it will also check out another few meteorites, if not close-up then with drive-by “shootings” to image the alien stones.

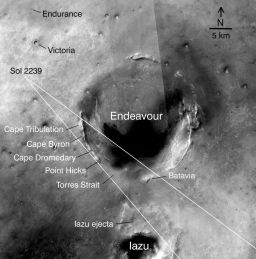

Between craters

Between cratersThis map of the region around Opportunity shows the relative locations of several craters and the rover in May 2010. The base map here is a mosaic of images from the Context Camera on MRO. The scale bar is 5 kilometers (3.1 miles).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Malin Space Science Systems / Washington University St. Louis

Meanwhile, Opportunity’s iron-detecting Mössbauer spectrometer began exhibiting some “anomalous behavior” this month. It seems to have garnered an extreme sensitivity to cold and is not working during the Martian evenings and late nights.

The good news is that it still seems to work just fine during normal business hours, one might say, or the warmth of the Martian sol.

The science team definitely wants to be able to use this instrument as it comes upon hydrated rocks outside Endeavour and once the rover gets to the clay minerals on the rim, so understanding this newfound sensitivity is important.

On Monday September 27, 2010, its Sol 2374, Opportunity hit the road. After putting 99.83 meters behind it, the rover revved up and drove again the following sol for 62.47 meters. A 120-meter drive was planned for yestersol, “the first 80 meters of which blind and the 40-meter balance done with autonav,” informed Nelson. “Given the available time, we expect to only complete about 95 meters,” he added.

On the fourth day, today, the rover rested. Now, as September comes to a close and October falls on calendar, Opportunity will keep on truckin’. “We’ve really been moving this month,” said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University. “And next month is more of the same.”

Given that the rovers are way, way past their warranties, it might seem risky to push this old gal so hard. “We hunt for that balance between aggressive driving and keeping the rover safe and we strive for it every day,” said Maxwell. “We have this priceless asset on Mars and we want to use it the best we can.”

Never too far from their thoughts though is the other priceless asset on Mars. “Sooner or later, we’re going to hear from Spirit,” assured Maxwell. “It’s going to happen.”

That kind of optimism, combined with something that could only be described as a special brand of mutual engineer-scientist respect and camaraderie, has served the team well, even turned the MER mission into a legend in its own time. On a practical level, it has enabled the team to demonstrate again and again during the last seven years, what honest commitment, extreme dedication, hard work, long hours, and integrity can create.

In hibernation

In hibernationSpirit appears on the shoulder of Home Plate in this FX image created by Glen Nagle, aka Astro0 at UnmannedSpaceflight.com, where the rover became bogged down in the sands of Ulysses at Troy. The rover took this panorama on her Sol 743, as she descended from Husband Hill and roved toward Home Plate, the circular plateau occupying the center of the image. Click to enlarge and you will see Spirit in the valley to its right. Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Glen Nagle

“We worked three-and-a-half years to get the mission off the launch pad and then another six or seven months to get it there,” reflected Maxwell. “In those four years of our lives, we skipped vacations, took time away from family members, sacrificed, and put everything on the line we could just for the hope, the hope we would have three months on the surface. That was our goal. To be coming up on seven years on the surface with no apparent end in sight,” he said, pausing, “well…it’s very much like being in Vegas and putting your last quarter into the slot machine and hitting the jackpot -- and then, having it just keep paying off. And the quarters are still flooding out.”

Spirit from Gusev Crater

Although for the last six months only sounds of staticky silence have been flooding out from Spirit’s location on the west side of Home Plate in Gusev Crater, when the rover does wake, assuming she does, the first robot to hibernate on the Red Planet will no doubt have many new riches to offer in lessons learned about robot survival on Mars.

Simulation of Spirit's position

Simulation of Spirit's positionThis artistic image -- in which Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover -- illustrates Spirit's predicament at the location in Gusev Crater known as Troy. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers the casual reader a glimpse into the present scene on Mars -- and this rover scribe thinks it's a pretty cool illustration. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

Until then, picturing Spirit silently parked along the edge of a shallow, long-hidden crater as the Martian spring winds kick up dust devils and swirls them across the landscape evokes, for MER followers and crewmembers alike, emotions that have pervaded this mission, not the least of which is a deep love (or, okay, like for those team members opposed to anthropomorphizing) for two golf-cart-size robot field geologists.

The general consensus is that sometime not long after Spirit’s last communication on her Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010), the rover lost so much energy that she tripped the low-power fault. As a result, she turned off all sub-systems, including communication, leaving only the clock and the emergency survival heaters for the two main power batteries on. And then she went into a deep sleep or hibernation mode to wait for the spring and summer Sun to warm her solar arrays and recharge her batteries. That, anyway, is what Spirit was programmed to do. As Squyres has put it in months past: “There is no reason to think the rover has done anything other than what it was supposed to do.”

This Martian winter, the rovers’ fourth, proved however to be the coldest. Spirit’s internal electronics clearly experienced much lower temperatures than pervious winters because its heaters could not always be powered when needed. That, along with recent models of Mars’ climate, have indicated that it’s possible the rover may have also tripped a mission clock fault. The problem is, there is no way of knowing since the team has had no ‘read’ on the rover since late March, and that complicates recovering Spirit. Suffice to say, recovering Spirit is not just as simple as -- the Sun shines down on the solar arrays and she wakes up, stretches and moves on. If only it were that simple.

“The way that the [rover designers] had envisioned the low-power and uploss fault happening was that something on the rover went wrong and by disconnecting the load you got rid of that [error], and the rover could rebound fairly quickly,” explained Nelson. “They also assumed that this happened during the prime mission when we had a considerable amount of power coming in. So the response calls for the rover to wake up in an autonomous recovery mode and phone home.”

In this recovery from the low-power fault, “Spirit will attempt to phone home, waking up every sol at a set time, nominally 12:15 pm, but probably a little earlier from clock drift,” informed Nelson.

34-meter antennas at Goldstone

34-meter antennas at GoldstoneThree 34-meter (110-foot) antennas at the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex, Mojave Desert, California. Goldstone is part of NASA's Deep Space Network, which provides radio communications for all of NASA's interplanetary spacecraft and is also utilized for radio astronomy.Credit: NASA / JPL

The team has been listening for Spirit with the Deep Space Network (DSN) and the Mars Odyssey orbiter for the rover’s autonomous recovery communication from the low-power fault since April, almost immediately -- even though they did not expect to hear from the rover for months.

But as the weeks passed, the reality of recovering Spirit got more complicated with the potential of a mission clock fault. If it turns out that Spirit has gone into mission clock fault, the recovery scenario changes fairly dramatically.

“In this case, the rover goes into a mode where it wakes up every 27 hours, and if there isn’t enough power, then it goes back to sleep and waits another 27 hours,” said Nelson. “When there is enough power to wake-up, the rover will get up for between five and 10 minutes, just long enough to power things up and check for a signal called solar groovy.” That signal essentially means the rover has 1.1 amps of power coming off its solar array. “If it’s not solar groovy, then it shuts down again,” said Nelson. If it is solar groovy, the rover in this state would not beep its team on Earth. Rather, it would listen for a message coming from Earth.

Whatever the case, whichever the scenario, the team is prepared and responding pro-actively, both listening and reaching out to Spirit with a series of pings in a procedure called sweep-and-beep, as reported in previous MER Updates.

By whatever means Spirit finally does open her ‘eyes,’ during her first brief wake-up from a mission clock fault, she will: reset the mission clock with a time known as recovery time; and set the alarm clock for every four hours. “We told the rover to use a time in the future, 9:45 in the morning on [Spirit’s] Sol 2600,” Nelson said. “That is a little after the summer solstice on April 9, 2011. Surely if we’re going to wake up we should have been awake before then.”

Once the clocks are set, Spirit will then begin waking up every four hours to see if she’s solar groovy. “Eventually, the rover going to wake up at a time when it is solar groovy,” said Nelson. “At that point, we will continue to fully wake-up the rover, instead of getting up and then shutting down right away.”

Spirt near Troy one year ago

Spirt near Troy one year agoYou can see Spirit in the upper right quadrant of this image about an Earth year-and-a-half ago by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO. The rover is at about 2 o'clock, appearing almost as if it's in Mars' spotlight. If you look closely, you'll see its form and head, and even the trail it plowed by dragging its broken right front wheel.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by Stuart Atkinson

In this complete wake-up, Spirit will signal its central processing unit (CPU) or brain to come back online in autonomous mode. “That means the rover won’t do much but keep itself safe,” Nelson reminded.

Spirit won’t actually be able to check tau or conduct other basic tasks because those are commanded sequences, which, with the low-power fault, will have been lost.

“On this first full wake-up, the original intent was that the rover would wake up and we would ask for it to execute a [communication] window in an hour and then it would “hang out and catch some rays.” [Ed. Note: This is the actual verbage from the official rover instruction manual. “Who says engineers have no sense of humor?” wondered Nelson.]

“Unfortunately for us, there is a parameter [in the program] called ‘up-too-long,’” Nelson continued. “Its purpose is to shut the vehicle down after a certain, set period of time, in order to maximize the amount of energy it can collect and it can collect more with the computer shut down.”

When the rover’s computer is ‘sleeping,’ it is using considerably less energy than when it is up and on, just like your laptop or desktop computer -- or your brain, ostensibly. “So the delta in energy between awake and asleep allows the rover to put that energy into the battery and charge it up some more,” Nelson added.

The up-too-long parameter is set at 20 minutes, “on the theory that the rover would be in low-power fault,” Nelson said. “This brief amount of time would allow the rover to wake up for long enough that engineers could actually do something with the vehicle -- 20 minutes is long enough to do a command into the vehicle, but it’s about as short as we could get by with to maximize recharging of the battery in the low-power fault.”

With the mission clock fault however, there is an unexpected and unintended consequence: the vehicle wakes up and expects to communicate using a comm window one hour later. “With that 20-minute up-too-long parameter, the rover wakes up and sets the comm window for an hour, and then shuts down after 20 minutes,” said Nelson. “And the comm window is volatile so -- poof -- it disappears!”

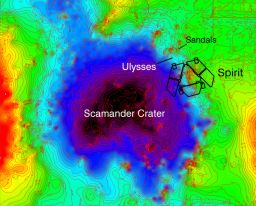

Topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy

Topographic map of Spirit's location at TroyThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed based upon Spirit's camera images of the location, taken before it got mired at Troy. The topographic model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State University

So, if Spirit wakes up and is solar groovy and producing 1.1 amps of power, she will stay up for 20 minutes, then shut down and continue this routine until she hears from the team.

“If it’s not solar groovy, the rover goes back to this waiting every four hours,” said Nelson “The effect of this is intended to wake-up Spirit later and later on successive sols, so eventually it will be waking up in the time period when its gets a solar array wake-up, another signal from the solar array indicating that the rover has 2 amps of power coming off it. “That, in turn, signals an autonomous wake-up to the CPU,” Nelson pointed out.

By commanding these four-hour wake-ups later and later, sooner or later the rover, theoretically, will wake up and listen. “Suddenly it will be locked into waking up every sol with the solar array wake-up -- and that was their intent,” Nelson explained. “In our situation though, with the up-too-long parameter set at 20 minutes, it means Spirit would try to communicate but would shut down too early and lose the window; therefore, Spirit would never talk to us and we would never have any indication that it was in fact trying to recover.”

That is the little dilemma that initiated the sweep-and-beep procedure last July, when the team decided to call the rover just in case it did trip the mission clock fault. “We’re now sending sets of commands, each one of which should provoke a beep,” said Nelson. “And we know a beep is five minutes of carrier-only signal, about the minimum that we can transmit, minimum energy usage, and yet still be able to detect it on the ground reliably. The sweep-and-beep is our attempt to get the rover to talk to us and of course it won’t do that until it is ready to start recovery,” Nelson summed up.

Yes, the sweep-and-beep will override any low-power comm session. “But we can, using the timing of the downlinks and by not sweeping and beeping for a few days, determine which fault mode Spirit is in,” Nelson clarified.

If in fact the rover wakes via the mission clock fault scenario, Spirit’s wake-up response will likely be characterized by three stages, said Nelson, as follows:

Free Spirit logo

Free Spirit logoOnce Spirit wakes up, the rover still must extricate itself from a sandy pit it encountered while driving along the edge of a shallow, once hidden Scamander Crater. The official Free Spirit site is at: http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/freespirit/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / John Howard

1) The rover will attempt a wake-up and finds insufficient power. The alarm clock rolls over, and rover tries again in 27 hours. (This "walks" the wake-up attempt later by 3 hours every sol; therefore, eventually it should happen at a favorable time.)

2) The rover attempts a wake-up and now finds sufficient power. It checks for solar groovy. If it doesn’t have the 1.1 amps of power that is solar groovy, it shuts down for four hours and tries again. The rover now wakes up every four hours instead of every 27 hours.

3) The rover attempts a wake-up and now finds solar groovy. It completes the wake-up, set comm window for an hour in the future then will "hang out and catch some rays."

Now several things could happen following this stage: Either solar groovy ends or the up-too-long duration of 20 minutes expires, said Nelson. The rover shuts down with wake-up in 21 hours. Or, in 21 hours, it wakes up, probably does not find solar groovy, so shuts down to try again in four hours. (It’s now 25 hours since the rover’s last wake-up with solar groovy.) Likely, the rover will continue with wakeups every four hours until energy improves.

If, however, the energy improves enough such that the period of solar groovy extends into the new wake-up time, the process repeats -- wake up, set window, shut down before window, wake up, and test for solar groovy an hour later. Eventually energy improves to where there is a solar array wake-up signal that "captures" the response so wake-ups always happen at about the same time of sol. “It is at this point that we can begin recovery operations,” said Nelson, “since we'll then know about when the vehicle is commandable.”

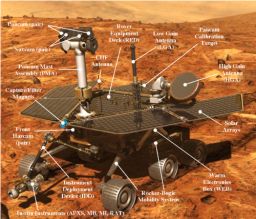

MER body parts

MER body partsThe Mars Exploration Rovers are robot field geologists designed with parts to substitute for the organs all living creatures that would need to stay "alive" and explore, as well as some super-human powers. Spirit and Opportunity, for example, each have a body that protects its "vital organs;" brains to process information; temperature controls, including internal heaters, a layer of insulation, and more; a "neck and head" formed from a mast for the panoramic cameras for a human-scale view; eyes and other "senses," such as cameras and instruments that inform the rover about their environment; an arm to extend its reach; wheels and "legs" for mobility; energy sources in the form of batteries and solar panels; and antennas for "speaking" and "listening."Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Got it? Clearly, waking Spirit up is a far cry from nudging your loved one, or setting a screaming-loud alarm clock knowing it’ll do the trick. But the MER team has its playbook, and no matter how Spirit emerges from hibernation, the engineers will find the way to recover their charge.

So far, Spirit’s sounds of silence are of no increasing concern to the MER team. Although power levels are expected to be improving with the advancing springtime in the southern hemisphere of Mars, atmospheric conditions historically deteriorate and the skies overhead get dustier because it’s the season when the infamous winds kick up. Thus, a response from Spirit has not really been expected until October or November.

Backstage at JPL and other places of MER gatherings, hope still floats and buoys the optimism that is a hallmark of this team.

Earlier this year when crewmembers regrouped and began to extricate Spirit from the sands of Ulysses at Troy, Maxwell ordered a bunch of FreeSpirit logo buttons and handed them out to team members. “Personally that’s one thing I’ve been looking for -- are people still wearing those buttons?”

The answer is yes. “Everybody I gave one to is still has it on, and people are wearing their Free Spirit shirts too. Everyone is still onboard,” he assured. “We have our fingers crossed. Eventually we hope we’re going to get lucky and I can’t wait to hear from our girl.”

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

After finishing its study of Cambridge Bay, Opportunity roved out of August and into September, really picking up the pace this month on its 19-kilometer (11.8 mile) journey from Victoria Crater to Endeavour Crater.

With the rover’s chronically ‘hot’ right front wheel looking good, the team decided in late August to kick it up a notch. “We had limited drives to no more than 70 meters to keep the right front wheel current in check,” said Nelson. That limit was instituted last year after the rover’s right front wheel actuator or motor continued to draw more than its fair share of current. Late in August however the team “temporarily” raised that to 90 meters, enabling the rover to drive for some 70 meters in a sequenced run and following that with about 20 meters worth of backward autonav.

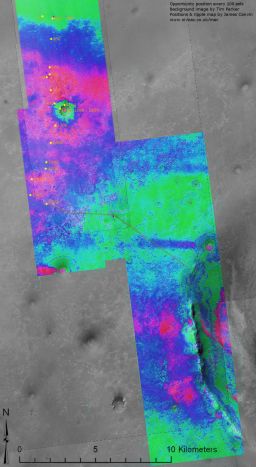

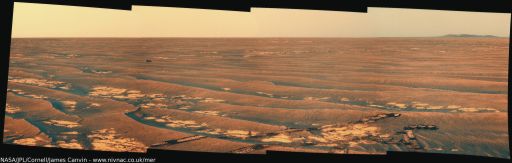

Opportunity position and ripple map

Opportunity position and ripple mapThis image shows Opportunity's position every 100 sols and was created from a background image by JPL's Tim Parker, with the positions and ripple map created by James Canvin. Santa Maria Crater is the little black dot to the right of the 2300 sol position. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / T. Parker / J. Canvin (see also: www.nivnac.co.uk/mer/ )

Using that combination of sequenced or blind backwards drives -- where rover planners chart a path based on visual imagery taken by the rover then command the rover to execute it -- and backwards autonomous or autonav drives, where the rover drives itself, using its own ‘smarts’ in hazard avoidance -- Opportunity put 89 meters (292 feet) behind her on Sol 2347 (August 31, 2010). And on the first day of September, Sol 2348, she added another 40 meters (131 feet) to her odometer.

The first drive of September was short, engineers noted, only because of limited driving time due to a late communication hand-over and not because the rover wasn’t energetic enough. In fact, Opportunity has been positively brimming with energy, producing 579 watt-hours of solar power at the top of the month under slightly hazy skies, with a tau registering around 0.461, and a solar array dust factor of 0.729, meaning the rover was making use of approximately 72-73% of sunlight penetrating its solar ‘wings.’

Overall, September was a month of newfound freedom for Opportunity. Through a combination of factors -- including the bedrock rich terrain, the fact that the terrain conforms better with the rover’s visual system, and ever-increasing sunlight -- this rover and her team have been really extending the drives.

The combination drive strategy “seems to have worked out pretty good,” Nelson confirmed. “Wheel currents have not been increasing” and the backward autonav drives have been adding “about 15% to the drive distance,” he said. “It may not be huge, but it is certainly significant. We like to do blind driving where we can, but of course we can’t drive farther than we can see.”

Now, with outcrop cropping up everywhere, there is much more variation in the terrain visuals. “In the 3-D correlater system that we work with, we can actually now get good range data out 150 to 160 meters -- and that really extends the amount we can drive each sol,” said Maxwell. Concerned about the problematic right front wheel, the roever engineers have been “gradually extending the drives from 70 meters per sol to about 90 meters, and then from 90 meters to 110 meters,” Maxwell offered.

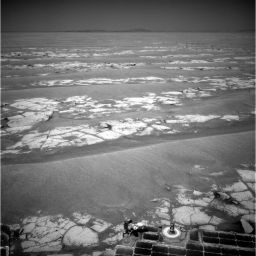

Halfway to Endeavour

Halfway to EndeavourOpportunity used its navigation camera for this northward view of tracks that it left on a drive from one energy-favorable position on the northern end of a sand ripple to another. The rover team calls this strategy hopping from lily pad to lily pad. The rover snapped this particular picture at the end of a 111-meter (364-foot) drive on its Sol 2353 (Sep. 6, 2010). It was this drive that took the rover past the estimated halfway point of the approximately 19-kilometer (11.8-mile) journey from Victoria Crater to Endeavour Crater. A portion of the Endeavour rim is visible on the horizon. In the nearer ground, exposures of bright-toned outcrop are visible between crests of darker, wind-sculpted sand ripples. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

On Sol 2349 (September 2, 2010), Opportunity roved again making tracks for 80 meters (262 feet) to the east. And after a Labor Day weekend holiday pause, the rover resumed driving again on Sol 2353 (September 6, 2010), heading east by south on that drive, for an impressive 111 meters (364 feet). The post-Labor Day drive pushed her odometer to 23 kilometers (about 14 miles) and took the rover past the halfway point of the approximately 19-kilometer (11.8-mile) journey from Victoria to the western rim of Endeavour.

The ‘road’ ahead looks as inviting as it does rover friendly. Crazy as it sounds Opportunity seems to be driving as well as she ever driven -- despite going it backwards, having her right front wheel toed in a tad, and having to hold her arm or instrument deployment device (IDD) out in the fisherman position.

The rover ripped into the second week of September on Sol 2355 (September 8, 2010), pushing the pedal to the metal and driving approximately 105 meters (344 feet).

That same sol, the rover ran some diagnostics on its Mössbauer spectrometer, which suddenly appears to have become ultra-sensitive to the cold of Martian nights. The test on this sol was conducted at warmer temperatures and the instrument functioned normally. The engineers and Mössbauer team went back to the diagnostic drawing board.

As the second week of September progressed, Opportunity continued making progress on the trek to Endeavour, testing new driving techniques along the way. On Sol 2358 (September 11, 2010), the rover added another 106 meters (348 feet) in a series of steps. The last segment of the long drive was a simulated test of autonomous navigation using rear hazard avoidance camera (Hazcam) imagery, while driving backwards.

Autonomous navigation is limited for backwards driving because the rover's low-gain antenna (LGA) is in the field of view for the Pancam mast assembly mounted cameras and so the team a couple of months ago instituted a workaround that basically involved the rover turning a little each way and snapping additional images to be ‘stitched’ together by team members and enthusiasts alike down on Earth, thus ‘erasing’ the LGA from the final view. The rear hazard avoidance cameras, however, are not obstructed by the LGA and further tests of the backward-autonav-Hazcam technique were planned.

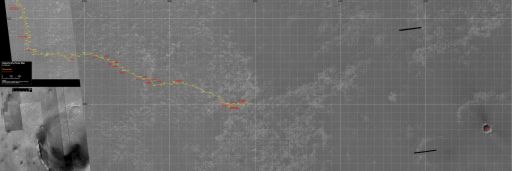

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis image, created with orbital images taken by the HiRISE camera, and Context camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, has been annotated by Eduardo Tesheiner, a senior member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com. It shows the rover's charted route from the San Antonio twin craters to its location at the end of this month.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / MSSS / annotated by E. Tesheiner

Opportunity also continued the investigation of the Mössbauer spectrometer on Sol 2358 (September 11, 2010) with a test at cold temperatures. In that test, the instrument exhibited the anomalous instrument behavior at both the start and the end of the 30-minute integration. Tests at other temperatures are planned to map what now appeared to be temperature-dependent behavior.

The roverfinished out the second week of the month with another drive on Sol 2361 (September 14, 2010), making tracks over 54 meters (177 feet) to the southeast.

Cruising onward into the third week of September, Opportunity locked on another large meteorite, positioned just off the charted route to Endeavour. “We were kind of bombing along the plains and the scientists suddenly went -- ‘Ohhh, shiny’ -- and there was a meteorite,” recalled Maxwell.

Ohhh-shiny

Ohhh-shinyOpportunity used its panoramic camera to capture this view of the iron-nickel meteorite nicknamed Oileán Ruaidh immediately after an 81-meter (266-foot) drive during its Sol 2363 (Sep. 16, 2010). About 45 centimeters (18 inches) wide from this angle, the meteorite was about 31 meters (102 feet) away from the rover when the picture was taken.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

On Sol 2363 (September 16, 2010), Opportunity drove more than 80 meters (262 feet) toward the meteorite that was quickly named Oileán Ruaidh (pronounced ay-lan ruah), the Gaelic name for an island off the coast of northwestern Ireland.

The rover also conducted yet another diagnostic test on the Mössbauer spectrometer, this time at an intermediate temperature. The instrument worked normally throughout the diagnostic test.

While the diagnostics of the iron-detecting spectrometer were to continue, there was consistently an error signal coming off the voice coil. “It has to do with using it at very cold temperatures,” said Arvidson. “The drive that vibrates the source acoustically wasn’t really operating properly at very, very cold temperatures. So the solution is don’t run it at those very cold temperatures.”

Why is the overnight cold bothering it now, when spring is warming Mars in the southern hemisphere? “We’re still talking Mars,” noted Nelson. “In middle of Martian day, it’s warm enough that this thing is still working properly, but late in the afternoon or evenings, we don’t get it to work right.”

That may seem really unfortunate for many who have been following this mission since lot of the Mössbauer integrations occurred overnight. “But we’re not going to do extensive Mössbauer investigations for a while, and by the time we get to these hydrated rocks and the rim of Endeavour, we’ll be beyond the real cold temperatures at night,” Arvidson pointed out. “The power source of the instrument is so depleted. Cobalt-57 has a half-life is 271.8 days, so we’re down many half-lives and we have to spend days and days making measurements now. We won’t do take that time anymore unless there’s something extraordinary. The next big campaigns will be when we see the hydrated rocks detected by CRISM, possibly as close at Santa Maria, and then when we get to the clay minerals at the rim.”

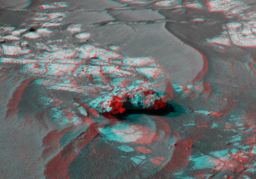

Oileán Ruaidh in 3-D

Oileán Ruaidh in 3-DOpportunity took this view of Oileán Ruaidh with its navigation camera on Sol 2368 (Sep. 21, 2010), after a drive the preceding sol to get close to the rock. The meteorite is about a half-meter (20 inches) long. The scene appears three-dimensional when viewed through red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left. The rover used its microscopic imager and the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer to inspect the rock's texture and composition.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

On Sol 2367 (September 20, 2010), Opportunity took a a 36-meter (118-foot) drive to approach Oileán Ruaidh, snapping pictures as she went, driving backwards with a deliberate drive-by in order to position the rover for a forward approach.

The following sol, the rover capped the third week of the month with a 9-meter (30-foot) semi-circumnavigation of the meteorite as her team planned for the rover to drive in close for an in-situ investigation with her IDD instruments.

Opportunity spent most of last weekend, September 25-26, 2010, checking out the composition of Oileán Ruaidh with her alpha particle x-ray spectrometer (APXS). The half-life of the APXS is 18.9 years so “it’s still going pretty strong,” said Nelson.

With this investigation of Oileán Ruadh, and another tempting target and probable meteorite called Ireland just 30-some meters away, the science team huddled. They decided that in the immediate future Opportunity would conduct a drive-by shooting of Ireland before it taking off on more long sprints to Endeavour, snapping pictures on approach to Ireland, again as it passes the shiny rock, and again as it gets 5 meters beyond it.

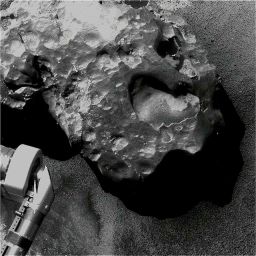

Oileán Ruaidh

Oileán RuaidhOpportunity took this image of the iron nickel meteorite dubbed Oileán Ruaidh last weekend, before getting back on the road to Endeavour Crater. "This might be the most beautiful meteorite found on Mars so far," suggested rover pet and aficionado Stuart Atkinson of UnmannedSpaceflight.com. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / enhanced by Stuart Atkinson

The science team members also considered and debated plans for Opportunity’s research agenda from here on to Endeavour. “We still have 10,000 meters to go to get to the rim,” said Arvidson. “Here’s the trade-off: we can drive and stop to make measurements -- we are interested in three types of measurements: the exotic rocks like the meteorites; the bedrock and changes in the bedrock; and soil and changes in the type of soil we’re driving over,” he explained. “But we’re not sure how long this mission is going to last.”

The decision was, like the team, logical and judicious. The plan stays the course. Opportunity will “make a beeline” toward Endeavour.

“We’re not going to stop and take any other meteorite measurements for another 3000 meters,” said Arvidson. Furthermore, the plan calls for the rover to stop only two or three more times to sample bedrock and once or twice for soil samples for the ongoing Victoria-to-Endeavour surface study.

And, yes, they are planning for the rover to stop at Santa Maria, just a short jag off the route. On this fairly “fresh” crater, it appears that the impact has “punctured through the bedrock,” as Arvidson put it. Now about 2.7 kilometers away, Santa Maria is luring the team for another reason.

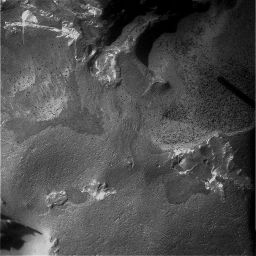

Oileán Ruaidh close up

Oileán Ruaidh close upOpportunity took this close-up image of the iron-nickel meteorite last weekend with its microscopic imager (MI).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University / processed by Stuart Atkinson

“As we get close to Endeavour, there’s a change in the characteristics observed by CRISM [onboard MRO] and we start to see hydrated rock that’s exposed, which we don’t see where we are today,” explained Arvidson. “Santa Maria might be close enough so that when it formed, it did so in those hydrated rocks. That’s one of the reasons we’re stopping.” Added Squyres: “We’ll see when we get there.”

That’s the long-term “baseline” plan, said Arvidson. “These are the guidelines that help shape the team strategy and objectives from here on, but all this goes out the window if there’s something really exciting that we see,” he underscored. “But the big pay-off is getting to the hydrated sedimentary rocks and the clay minerals on the rim, at Cape Tribulation.”

It could be that the race to find phyllosilicates will be over before Curiosity even launches next year. That of course remains to be seen, but the road ahead looks marvelous for Opportunity and the outlook is as bright as one could possibly dream it could be at this point in the mission, more than six and a half years after landing. “There’s a good few kilometers where we’re on outcrop and then a few kilometers where it’s just flat -- as flat as a tabletop. So it might just as well be the case that we’ve been through the hard part and from here on, metaphorically speaking, it’s all down hill,” said Maxwell, echoing the expectations of others.

In recent sols, the team further lifted Opportunity’s drive limits to 140 meters per sol. “That is a pretty long drive,” admitted Nelson. “We don’t always have the time to do such long drives, but we think the rover can do longer backward autonavs, because the rover is now moving into terrain where there’s a lot less sand and a lot more outcrop. That gives the rover -- and us -- plenty of features to use in our calculations and we anticipate seeing even longer drives because we have the energy and because it hasn’t been hurting the wheel current. We just haven’t seen the run-ups in current that were indicative of problems or at least of concern to us, like we did when we were driving forward.”

Bill Nye eyes Curiosity

Bill Nye eyes CuriosityBill Nye, the new Planetary Society Executive Director, stopped in at a press gathering at JPL for the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover Curiosity earlier this month and watched the new roving robot practice using its arm. Although this bigger, stronger, faster rover will not launch until next year, there is already a race on between Curiosity and and Opportunity to see which can find and study phyllosilicates, the group of minerals that includes clay minerals, which form in watery conditions. While Curiosity is charged with finding these water bearing minerals, Opportunity is en route right now toward clay minerals at Cape Tribulation on the rim of Endeavour.Credit: A.J.S. Rayl

Given that these rovers have been roving around for nearly seven Earth years old, most of which has been past their “warranties,” such hard-driving almost seems like an awful lot to demand. The MER engineers are ever cautious though and pretty darn skilled at the balancing act after all these years of exploration.

“It certainly is a concern and we do keep a careful eye on all the data we get back from the rover to make sure what we’re commanding is not causing a problems,” said Maxwell. “And we need to keep looking on the horizon -- that’s why we’re driving backwards and not forwards -- we’re keeping an eye on the health of Opportunity.”

On the other hand, not driving the rover presents problems too, Maxwell pointed out. "If we drive 70 meters per sol, instead of 120 meters per sol, maybe that means it will take another year to get to Endeavour, and maybe it’s in that year or six months that Opportunity dies. Maybe we could have made it to Endeavour, but we didn’t because we were so conservative,” he considered. “It’s very hard to get the guess right, especially when there are so many unknowns. We don’t know what’s going to slow Opportunity down at the end or what’s going to kill her. We try to make the best assessments we can, the best judgments we can to achieve the best balance. We strive for just the right amount of aggressive driving, but not so aggressive that we damage the vehicle, and yet not so conservative, so frightened that we don’t use the vehicle to its fullest potential.”

And so the rover drivers continue to experiment with new roving techniques to get Opportunity to its next big destination sooner rather than later. While Maxwell declined to detail exactly what the rover drivers have up their sleeves, he did say: “If everything goes my way there’s going to be some exciting things happening -- soon. Hopefully we will start employing some new tricks and do what we can do to make this second half not only be huger, but maybe even go by even faster.”

The road ahead from Oileán Ruaidh

The road ahead from Oileán RuaidhFrom her parked position at the meteorite Oilean Ruaidh, Opportunity took this drive direction mosiacked image of the 'road' ahead. Check out the tracks, ripples, bedrock, the meteorite named Ireland in the distance, and and the 'twin peaks' on the north rim of Endeavour.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / processed by James Canvin

Opportunity put another half-mile on her odometer in September, and in coming sols the rover will continue to focus on her prime directive of “drive, drive, drive,” as Squyres has so often put it. But tomorrow, the rover will take a little time to help her less fortunate twin.

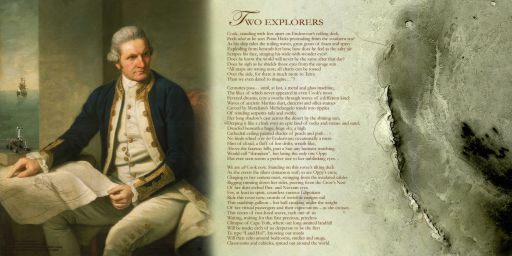

Two Explorers

Two Explorers: A Downloadable MER Poemster

MER poet Stuart Atkinson and artist Asro0/Glen Nagle, both of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, joined forces to present another in what should become a series of MER "poemsters.'

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Maas Digital / Cook image by Nathaniel Dance, NMM London /poetry by Stuart Atkinson / artistic composition by Glen Nagle

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth